In 1539, Anne of Cleves met her hot-tempered fiancé, King Henry VIII, for the very first time – and to say it was awkward might be one of the biggest understatements in courtship history. Of course the union was politically calculated, but a flustered Henry proceeded to tank the marriage after claiming she looked nothing like her portrait. Personally, we want to hear Anne’s side of the story, but the incident still begs the question: just how long has filtering, photoshopping and catfishing been warping our perceptions of each other? Here’s a portrait of Anne with a slightly different perspective:

“I like her not! I like her not!” were the gavel-slamming words of Henry upon seeing Anne. Fair enough. Except this woman had just taken a goddamn chariot all the way from Germany, so some compromise had to be made. Henry proceeded to throw a verbally abusive tantrum, calling her a “Flanders Mare,” accusing the original portrait he’d been shown of masking her large hooked nose, and covering up her smallpox marked skin. His court promptly made moves to annul the marriage, provide Anne with a fat settlement, and dubbed “the King’s Beloved Sister.”

Today, most historians agree she was far from a “Flanders Mare” in appearance, and that she’s gotten way too much flack for any alterations. Historians agree that there was probably a tad bit of “photoshopping” (i.e. a smaller nose, no warts) but if anything, it might’ve been Anne’s intolerance for BS that shook Henry (she was very sharp, and not to be trifled with).

Anne luckily got out of the situation with her head, and her dignity. It was actually Henry’s chief minister and matchmaker, Thomas Cromwell, who was charged with treason for organising the marriage.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that his later relative, Oliver Cromwell, was such a vocal champion of realistic portraiture; he famously insisted that all his commissions contain the “roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it.” Here’s his iconic #NoFilter portrait:

Insisting on the inclusion of “roughnesses” in male portraiture isn’t exactly earth-shattering or risky for men, but it does underline how important it was for prominent figures to visually codify their values in everything from the secret language of still lifes, to portraits of themselves in intimate and watershed moments. Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801-1805) by Jacques-Louis David comes to mind. For one, the sitter wasn’t even Napoleon himself, but the artist’s own son. Talk about a major catfish moment:

“A resemblance? It isn’t the exactness of the features, a wart on the nose which gives the resemblance,” said Napoleon in defence of his refusal to pose, “It is the character that dictates what must be painted…Nobody knows if the portraits of the great men resemble them, it is enough that their genius lives there.” In truth, Napoleon was about 5 ft 6 in (167 cm) tall, and he crossed the Alps on a mule that spring. An 1850 painting of the same moment by Paul Delaroche proves a much more accurate visual account, and as a fixture of the emerging “Realism” camp, Delaroche wasn’t trying to slight to Napoleon’s legacy in his depiction but highlight his perseverance. Hence, the inclusion of snow – the only embellishment, but one that signalled endurance.

In that sense, portrait artists were like brand stylists. If you knew what approach you wanted for your own public image, you needed only to seek out the right painter.

Take the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V of the Habsburg Dynasty, a powerful lineage of intermarrying monarchs, many of whom shared a distinctive family feature, known amongst art historians as “The Habsburg Jaw”. Despite appearances, the two side by side portraits above are indeed of the same monarch, Charles V, painted just 17 years apart. It would appear that as the monarch matured, he became more familiar with the artful tricks of portraiture, which he could use to draw the attention away from his chin (and redirect it towards his nether regions).

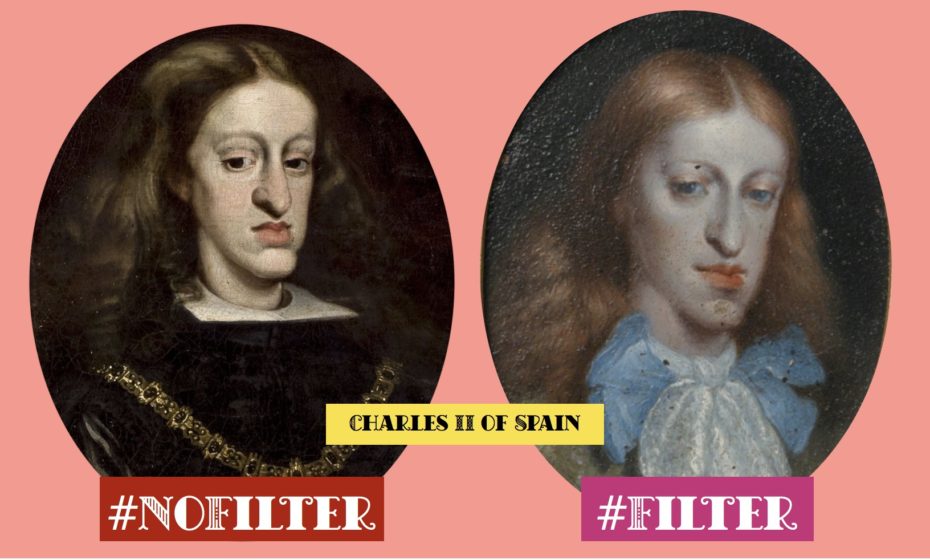

A sharply jutting chin, oversized lower lips and long noses are commonly-seen features in the Habsburg family portraits, perhaps most noticeable in the paintings of Charles II of Spain a few generations later. Modern genetic researchers have recently determined that the distinctive Habsburg Jaw can be associated with the family’s habit of inbreeding (and lots of it) – which was handy for maintaining the dynasty’s power over most of Europe for several centuries. Hereditary health defects such as epilepsy, gout, depression and dropsy were also a result of the inbreeding and by the time Charles II was in his thirties, his health was noticeably deteriorating. To avoid the public knowing about the king’s health conditions, his family commissioned artists to depict a strong and healthy young man, an image that was quite contrary to reality.

As for the Queen of filters, the crown undoubtedly belongs to Elizabeth I. During the course of her reign, she became a public icon, but through a carefully cultivated image. The Tudor monarch was “as a master of artifice who crafted and controlled the mask she presented to the world, particularly as she grew older and fell victim to increasingly poor health”, notes The Smithsonian. “Portraits became a key method of maintaining the myth of the queen’s youthful beauty […] Toward the end of her reign, Elizabeth issued a ‘face template’ that portrait artists were commanded to adhere to”.

Modern portraiture arguably, is no different. Political figures continue to turn to hyper-flattering portraiture. American artist Ralph Cowan made quite the career painting controversial dictators and powerful figures while glossing over the darker realities of their legacy with his paintbrush. Typically, the result is a fantastically kitsch departure from reality.

The obsession with augmenting our appearance is perhaps nothing new, but with the Smartphone apps at our fingertips becoming far more accessible and advanced by the day, you might say we’ve entered an entirely new age of deception. And unless we start learning from history’s mistakes, prepare to be disappointed.