In chapter five of Jack Kerouac’s timeless 1960 travelogue, Lonesome Traveller, the great American novelist takes us to New York to meet the inner circle of bohemian artists and beatniks in Greenwich Village:

“Let’s go see the strange great secret painters of America and discuss their paintings and their visions with them — Iris Brodie with her delicate fawn Byzantine filigree of Virgins — Or Miles Forst and his black bull in the orange cave. Or Franz Klein and his spiderwebs. His bloody spiderwebs! Or William de Kooning and his White. Or Robert De Niro.”

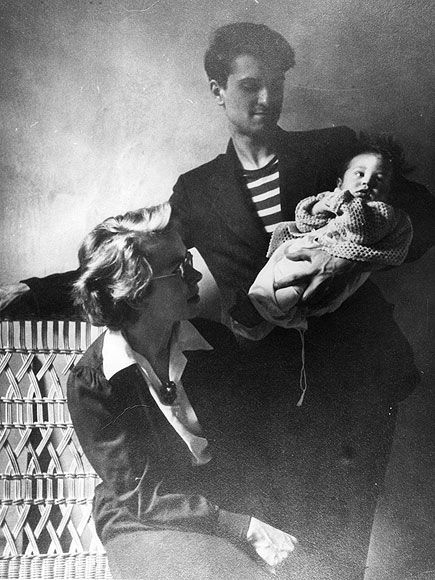

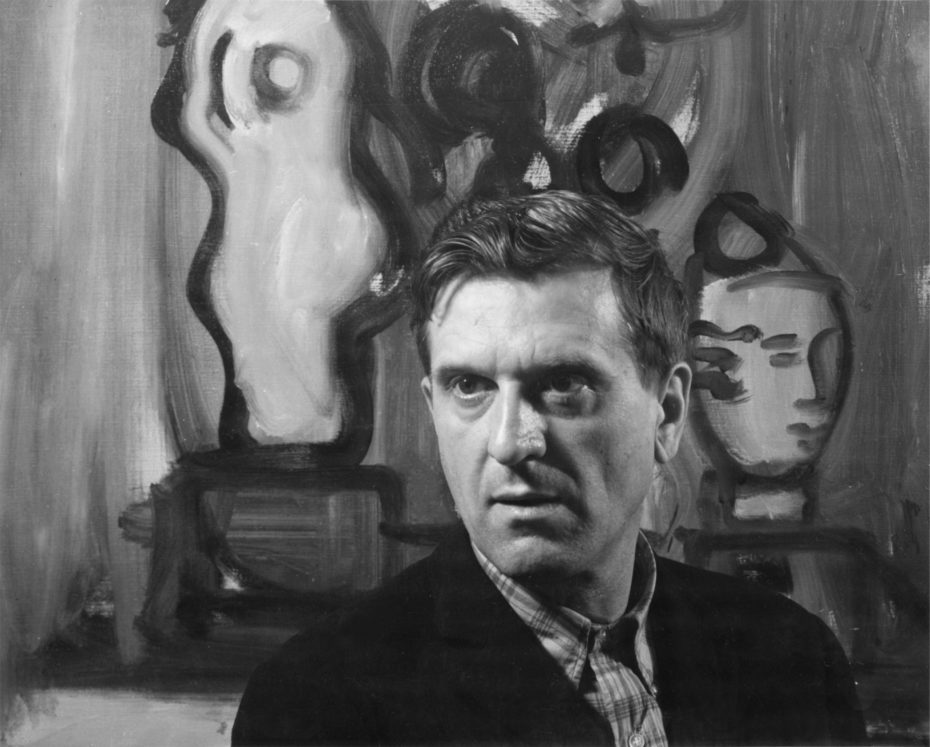

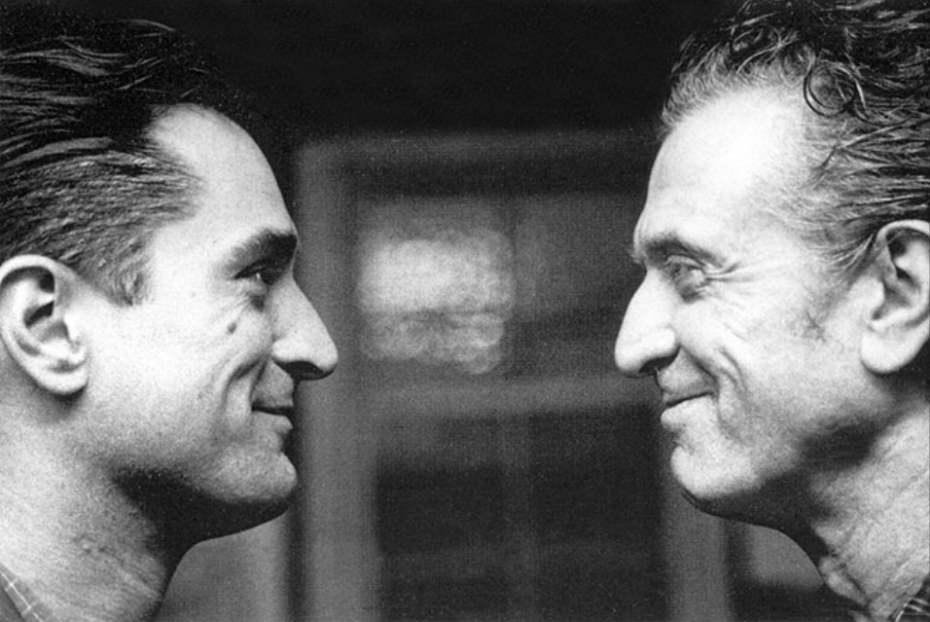

Robert De Niro?! As in you-talkin-to-me? Well, close. Unbeknownst to many, Robert De Niro Sr. was an abstract expressionist painter whose work was shown in 1945 at Peggy Guggenheim’s “Art of This Century” in New York; a leading gallery which became one of the major crucibles for the emergence of the New York School. Artists on show included Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, as well as Salvador Dali and Picasso – and Robert De Niro Sr. Below, is a photograph of the bohemian painter with his young son, and future Oscar-winner, sitting on his lap. Their New York family story sheds a tender light on bygone Greenwich Village, and the stage it set for one man’s exploration of art, sexuality, and acceptance.

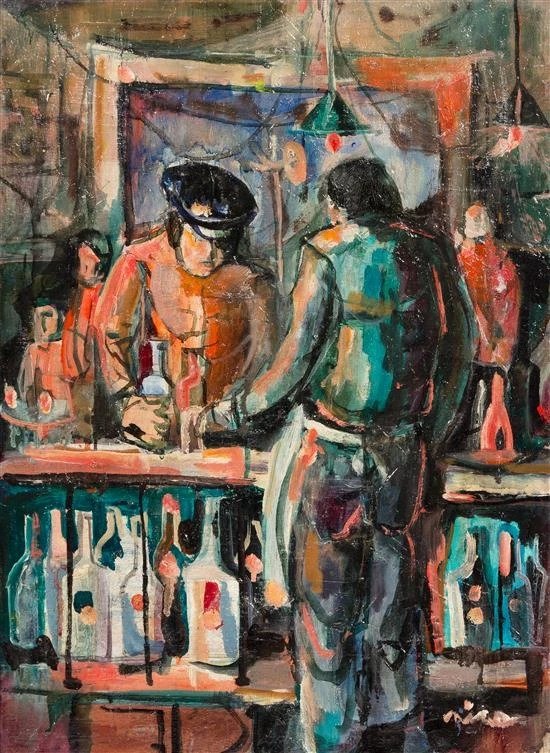

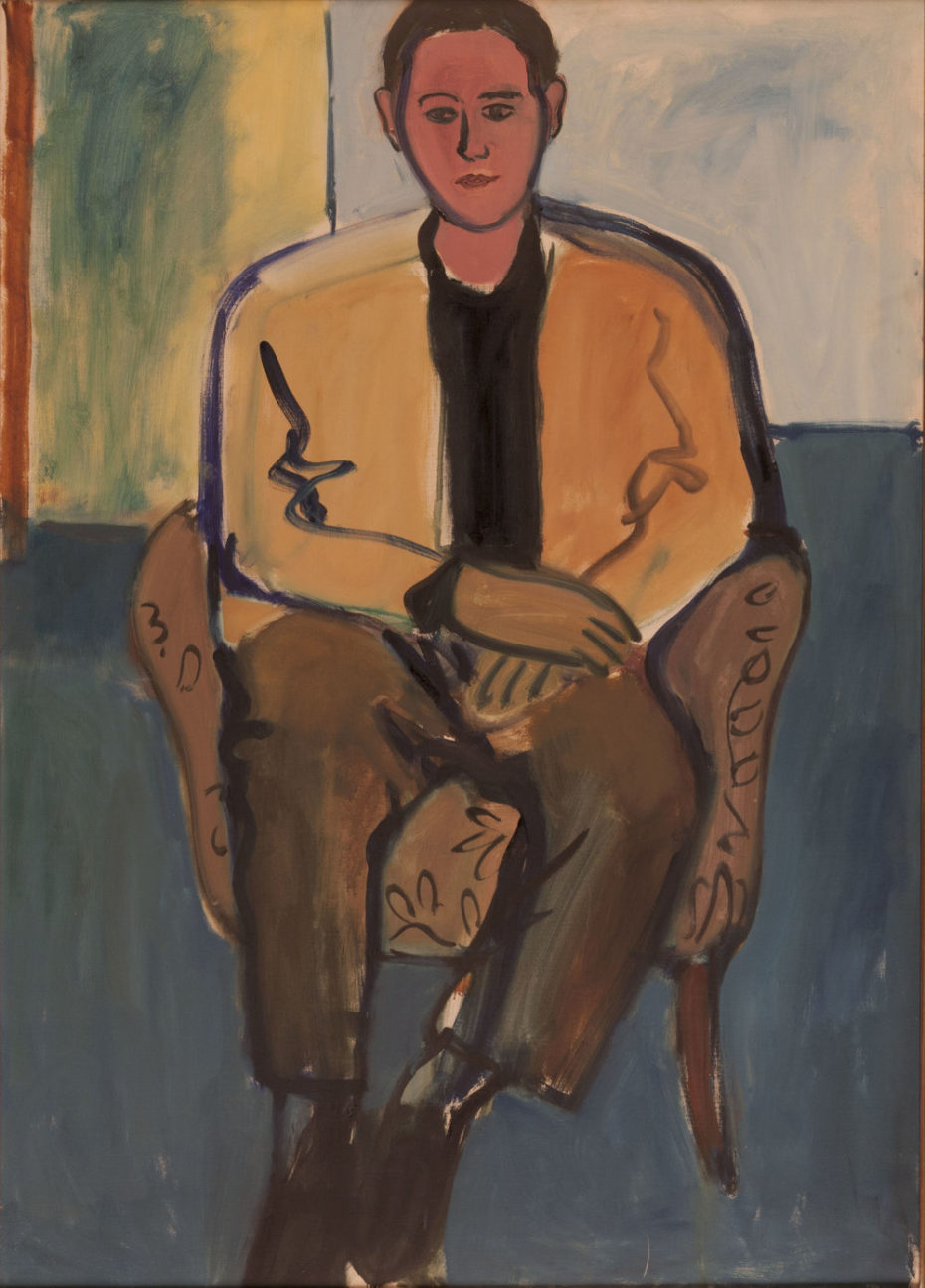

Greenwich Village was already the cradle of bohemian life when De Niro Sr. moved there in the early 1940s with his new bride, and fellow artist, Virginia Admiral. They met while studying under Hans Hofmann – an immense figure of Abstract Expressionism – at his Provincetown summer school. If his wife’s name rings a bell, it’s because her artworks are now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, and were also featured by the iconic art patron, Peggy Guggenheim, who would give De Niro a breakthrough show with Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko in 1945. After his participation in the Guggenheim show, critics were hungry for more. “De Niro succeeds in keeping every inch of the canvas alive,” wrote Thomas Hess of another show in 1951. “The result is a feeling of luxury, poise and affable richness, combined with a sort of nervous impetuosity.”

Once the newlyweds set up house in the Village (they hopped around until landing in a place on Bleecker Street) they were rubbing shoulders with likes hippest countercultural figures, like Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin; dancer Valeska Gert and writer Tennessee Williams.

But De Niro had been fighting a secret battle. “He wrote a lot about his life in his journals, which gives me an idea of what he was going through,” says Robert De Niro Jr. in a video interview. He proceeds to read an excerpt: If God does not want me to be a homosexual, about which I have so much guilt, he will find a woman whom I love, or who will love me, or at least create an interest in me in women as sexual partners.

Even for a man of so much expression, it was painful to navigate life as a gay man in a straight world. Before the Stonewall Riots and the LGBT activism of the late 60s, it was a scary time for anyone to be openly gay.

Bob Sr. and his wife Virginia were part of an underground artistic community in Greenwich Village that was bursting with vitality and secrets. During the height of McCarthyism, the De Niros held a salon of sorts out of their apartment on Bleecker Street, entertaining all kinds of Marxist characters, bohemians, artists and critics. They discussed Freud, erotic literature and Trotskyism.

As early as the the 1910s, Greenwich Village was slowly becoming a haven for diversity and alternative social and political thought. Gay men and lesbians frequented the many cheap Italian restaurants, cafeterias, and tearooms that the Village became known for. By the end of WWII, the neighbourhood was officially home to covert middle-class gay and lesbian commercial enterprises “where men and women built unconventional lives outside the family nexus.” (George Chauncey, Gay New York).

It was rumoured De Niro Sr had affairs with Jackson Pollock and playwright Tennessee Williams. Shortly after the birth of his son, Robert Sr came out as gay, became separated from Virginia and began a relationship with Robert Duncan, the poet. Duncan was also Virginia’s close friend, and it created tension amongst their circle of friends. Anaïs Nin wrote in her journal about an argument they’d had over it.

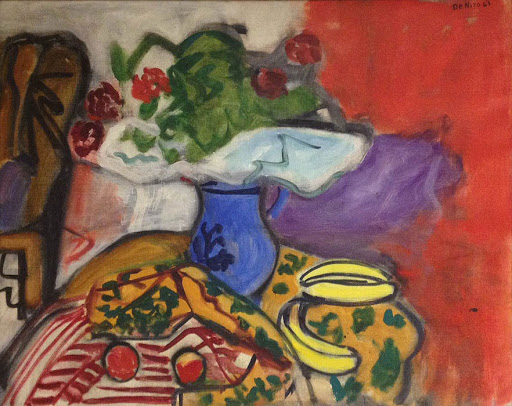

In the 1960s, his father ventured to Paris to take inspiration from Modernists like Matisse and paint the surrounding countryside. He had no luck with the Parisian gallerists, however, and the rejection sent him into terrible rages. In his late teens, a young Robert De Niro Jr followed his father to Paris, and eventually rescued him from a downward spiral of depression, putting him on a flight back to New York.

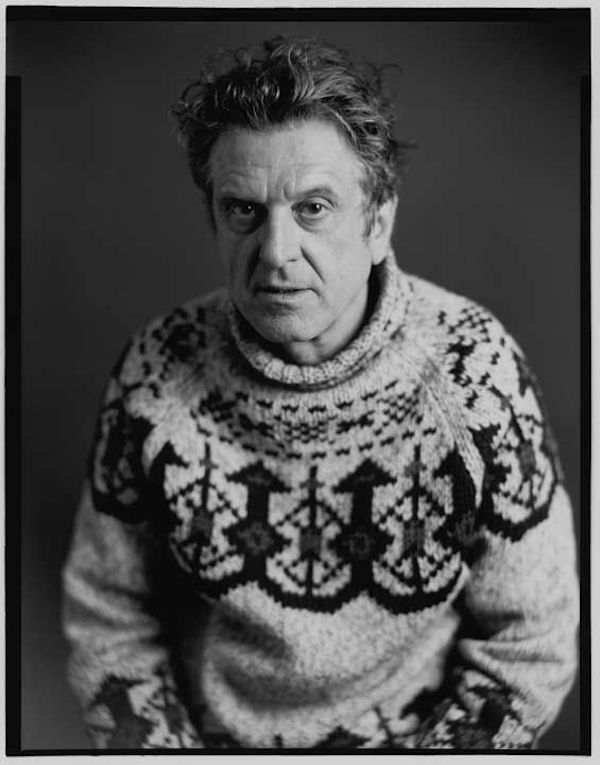

But even back home, his career had slipped out of the critical spotlight. The artist’s initial success was eclipsed by the bright acrylic appeal of Pop Art, and despite being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1968, his name was quickly forgotten in the fast-changing American art scene. De Niro continued to paint in relative obscurity until his death in 1993 at the age of 71.

The late actress Shelley Winters, who gave De Niro Jr one of his first screen roles in Bloody Mama, once told The New York Times, “Bobby will never talk about what made him the way he is, but I suspect he must have been a lonely kid […] his father’s sexuality and depression must have played a central part in it. Acting may well have been a form of self-therapy, as well as an attempt to come to terms with his ambivalent feelings towards his father”.

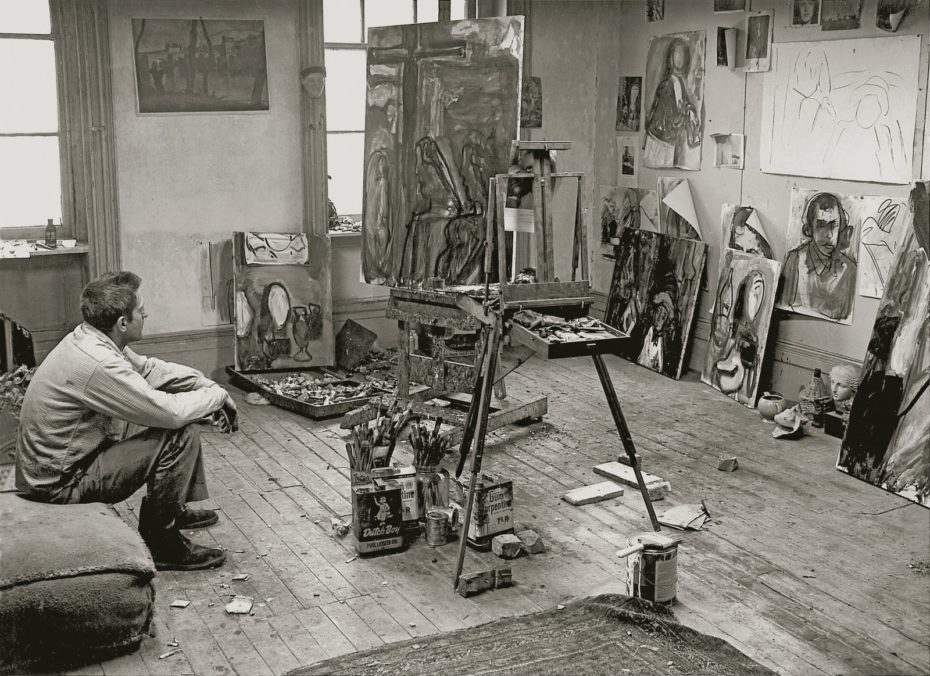

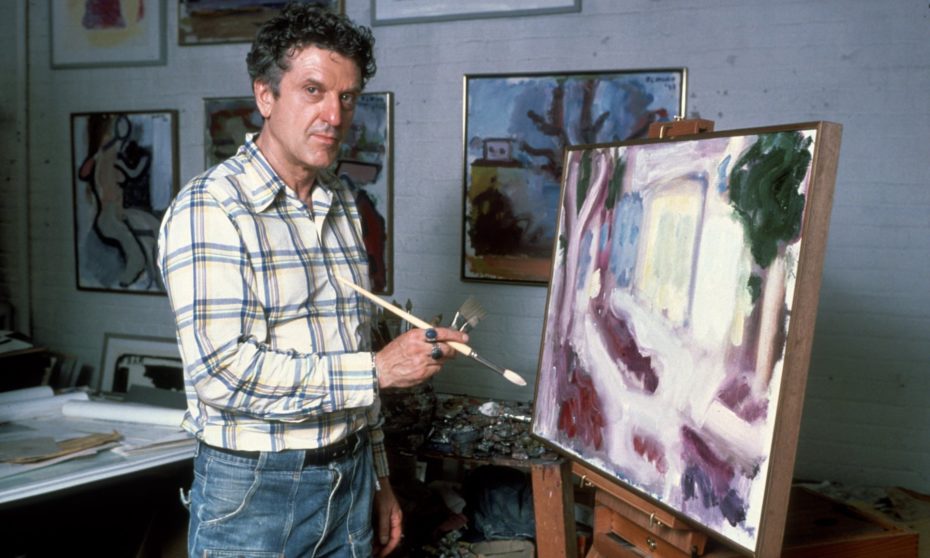

“I was very proud of him,” says De Niro himself, who has been known to clam up on the subject of his father’s depression. He prefers to recall fond memories of the smell of turpentine and paints when he’d visit his father in-studio – a place which, he says, he has kept 100% in-tact since his father passed away in the 1990s. “I even have his dry cleaning hanging in the closet in bags,” he told Newsweek in 2012.

When he was seventeen, Robert spent four months hitchhiking around Europe, clutching a sign painted for him by his father that read, “Student Wants Ride” in English and Italian. That sign took him to Venice and Rome and glamorous Capri, where he told almost everyone he met that his father was a famous painter in Paris.

What does De Niro Jr. think of dad’s work? “It’s not flippant. It’s real. Substantial,” he said in a 2019 interview with Tom Power for CBC. While they never had any grand discussions on art, culture or the “meaning of it all,” he says that they shared an ineffable understanding. They’d go to the movies, and see Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. Later in life, they’d go to see De Niro Jr.’s movies, of which De Niro Sr. was equally very proud. But above all, he says they were able to just sit in a room together, in total and utter silence.

Did De Niro Jr. ever think of picking up a paintbrush? Not really, according to his CBC interview, in which he gets just nostalgic enough, before retreating back into that signature De Niro coolness. “I just was never interested, [just as] my kids aren’t interested in [doing] what I do.”

But in his own way, Robert De Niro the actor his been very involved in the revival of his father’s contribution to the arts. In a moving HBO documentary, the Oscar-winner reads from his father’s journals and notebooks where he’d written about his hopes and dreams; that one day, his work would be rediscovered and given the critical recognition that had eluded him in his later career.

His works can now be seen in the Brooklyn Museum, Baltimore Museum of Art, Mint Museum, Hirshhorn Museum, Kansas City Art Institute, and the Yellowstone Museum Art Center, as well as The Greenwich Hotel.

You can also learn more about the artist’s work through his estate and on DC Moore Gallery’s website.