Yearning for the days when you could travel freely? Longing to roam foreign cities without worrying how long you might have to quarantine; or discover new cultures without the added barrier of a mask? When we get all that back, how will you experience it? From behind the screen of your phone camera or by savouring every moment? If you’re intent on being a carpe diem kinda traveller, you might be intrigued by the concept of the “photo veritable” or the “real photo postcard”, a long-forgotten souvenir from an era when we weren’t all carrying digital cameras as an extension of ourselves…

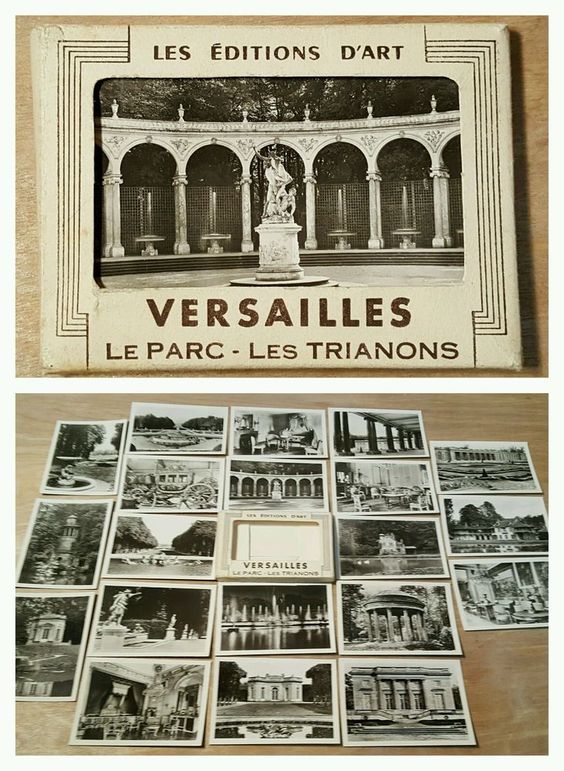

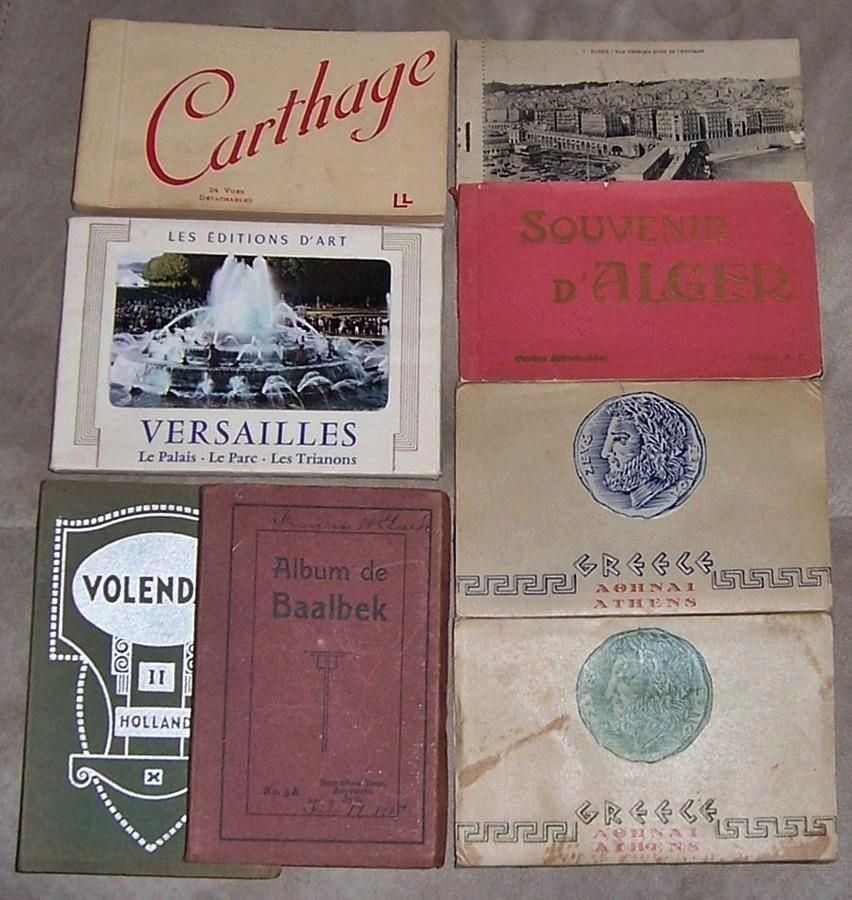

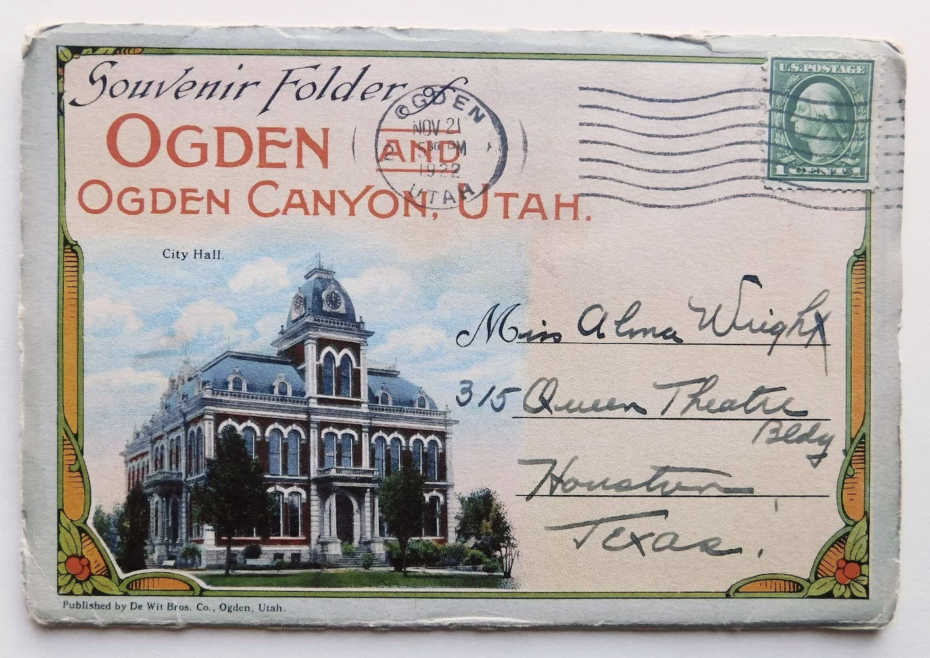

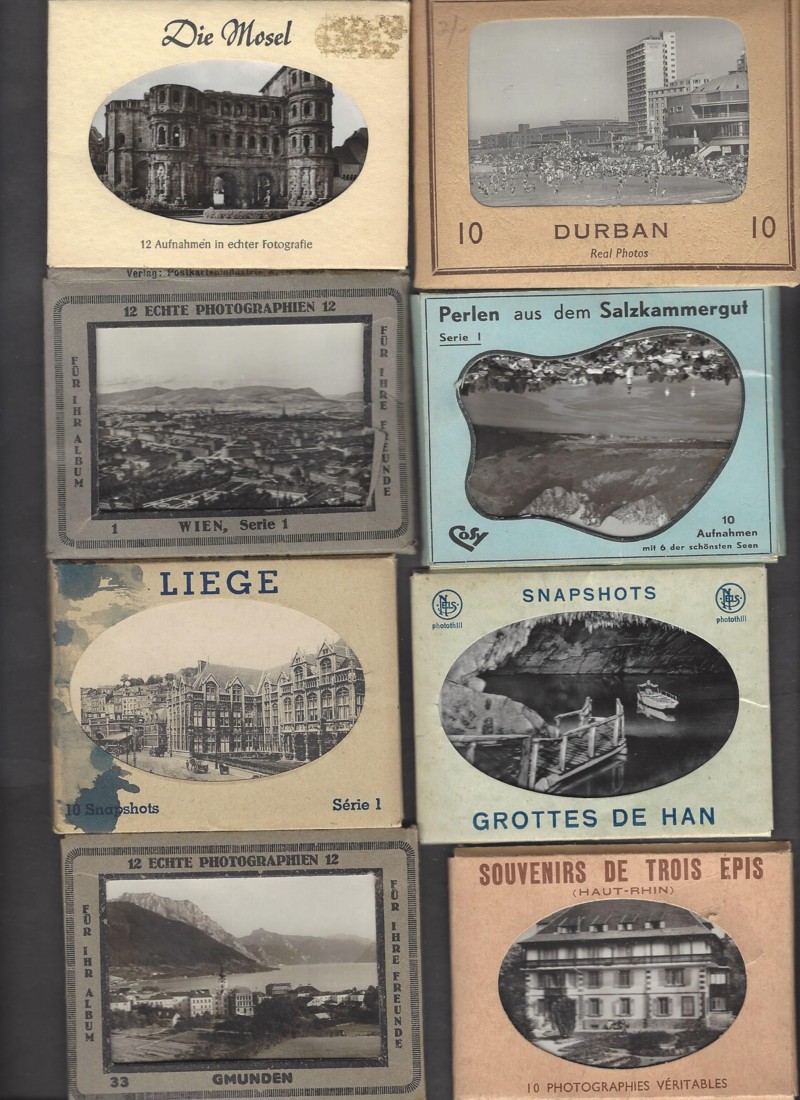

You may have come across them before, unknowingly glancing over them at a yard sale or flea market next to a bin full of unclaimed vintage photographs or travel ephemera. They’re an often overlooked gem of vintage travel souvenirs, which were once widely sold in paper cartons or “souvenir folders” at tourist attractions or gas stations.

Think of it like a pre-prepared vacation album, alleviating the pressure of snapping the perfect photographs to show off back home, or in our case today, upload to social media. At a time when personal cameras were a luxury, albeit largely unreliable, bulky and generally not yet second nature to us, you could show up to your travel destination, enjoy it to its fullest and purchase a folder of 20 photographs for just a few pennies at the end of your visit.

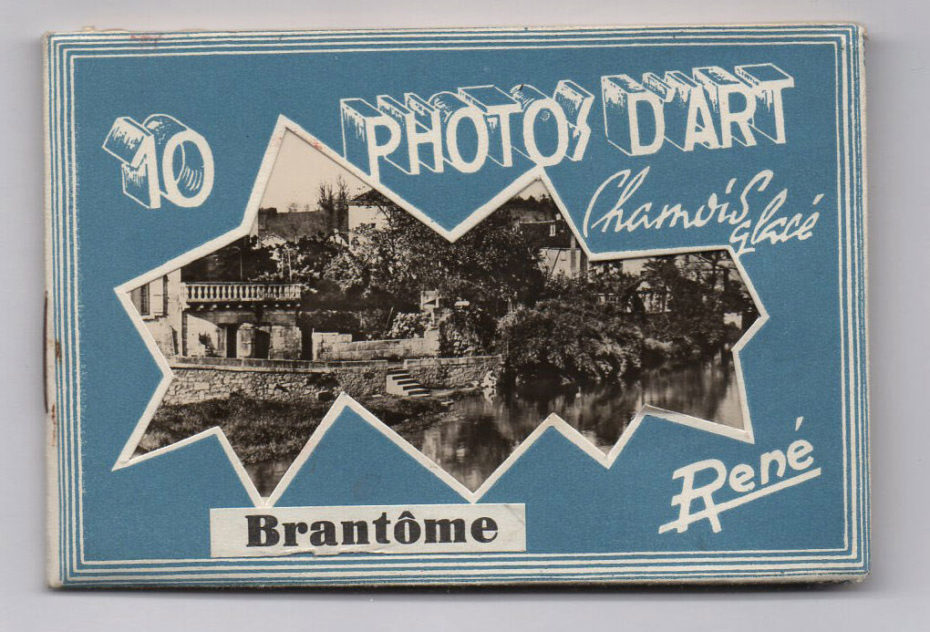

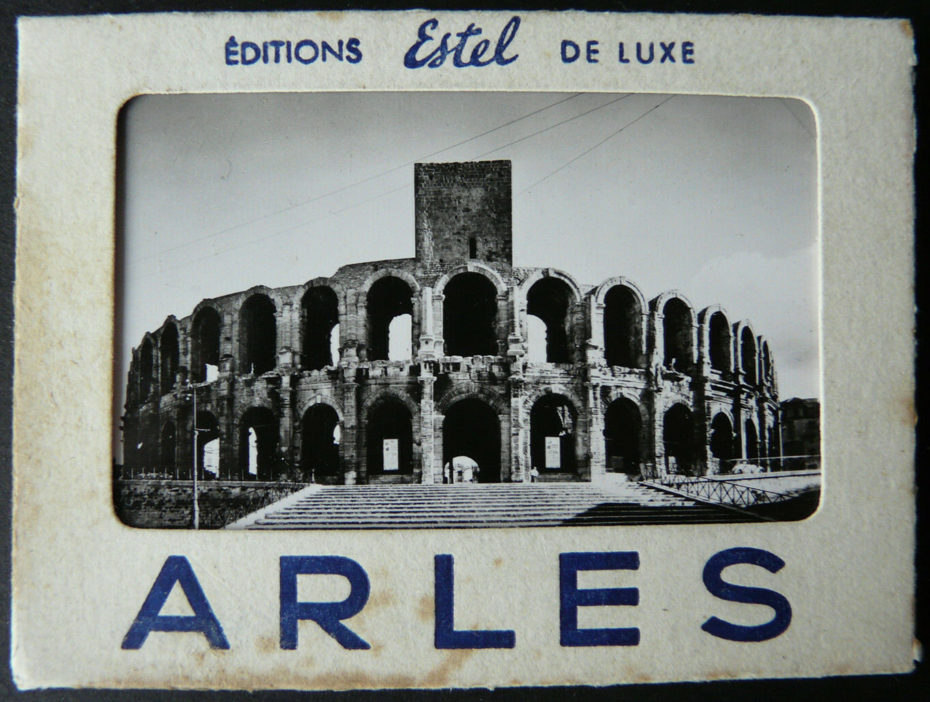

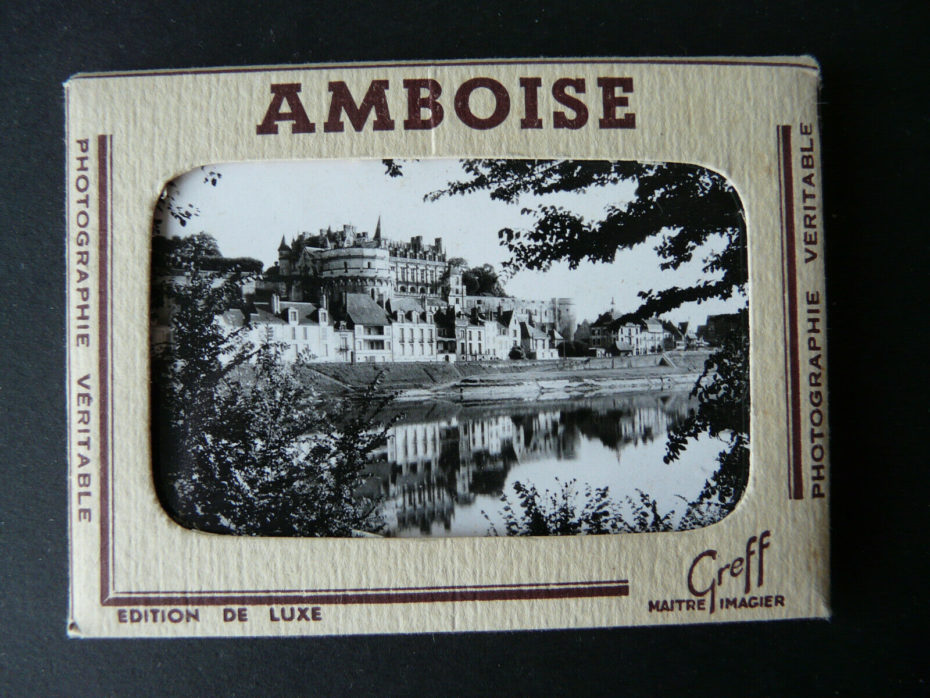

You could even claim them as your own personal snapshots. Because who would ever know? Get rid of the packaging, keep the prints and no one back home would be the wiser! This might even explain why souvenir photo packs are so difficult to find and unfamiliar to the average collector, despite their original popularity that soared throughout Europe and North America. But if found intact, their eye-catching packaging design is indeed a delight to behold. The vintage fonts and creative graphics on some of these things would make any typophile swoon.

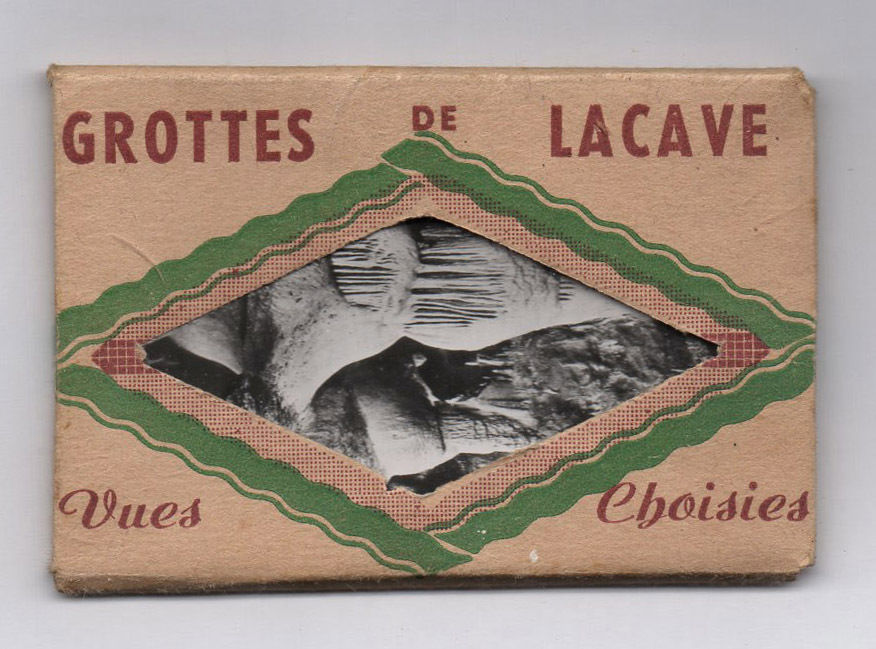

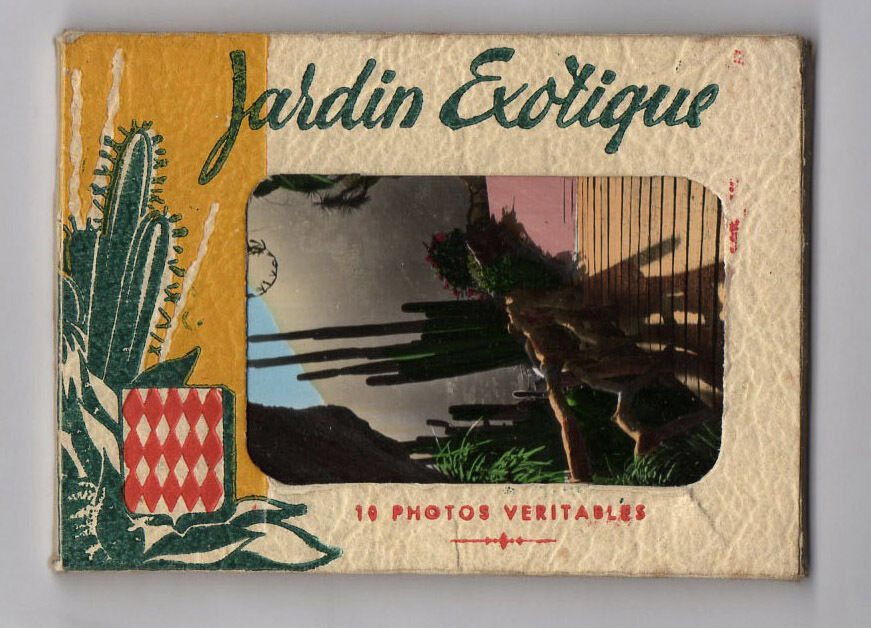

They also carried an element of surprise with their distinguishable cut out windows, giving a preview of just one of the images inside. We imagine store clerks wouldn’t have taken too kindly to customers unpacking the folders, so you would’ve been left to judge the series by that preview alone and the design of the exterior carton.

Not all souvenir photo packs contain photographs with postcard features on the back, but it was in 1907 that Kodak first introduced a service called “real photo postcards,” which enabled customers to make a postcard from any picture they took. Gotta say, it’s a little less catchy than “Instagram”, but the term was likely chosen to help distinguish the real photo process from the lithographic process historically used in making postcard images. Kodak also produced a folding pocket camera at the time, the No. 3A, which used film specially designed for postcard-size prints, allowing enterprising amateur photographers to travel across country to various sites and easily reproduce their own images to sell to tourists or collectors alike.

You can often tell which albums contain more unique prints that were captured by local amateur photographers and which ones were mass-produced by companies.

The vast majority of real-photo postcards were created in black and white, although some images were hand-coloured after printing. Some companies produced them on a long strip of folded paper accordion style. The containing folders were also sometimes printed with a stamp box and address lines on the back so that they could be mailed in their entirety to loved ones. What a treat that must have been to receive!

Old House Journal notes that local entrepreneurs hired photographers “to record area events and the homes of prominent citizens … important buildings and sites, as well as parades, fires, and floods. Realtors used them to sell new housing by writing descriptions and prices on the back. Real photo postcards became expressions of pride in home and community, and were also sold as souvenirs in local drug stores and stationery shops.” At the time, the real photo’s popularity rendered traditional cabinet cards obsolete, until its own demise came with the birth of low-cost accessible cameras in the 1960s.

In a world where cameras are now inescapable but our freedom to travel is so precious, could it be time for a comeback for those wishing to live (and travel) in the moment?