“Pure psychic automatism.” That was Ithell Colquhoun in a nutshell, according to fellow Surrealist André Breton. The flattery is a bit of a suprise, given that Breton – one of several founders of a movement that has made little room to uplift its women – was somewhat of a vocal hater of women in the arts, despite the very clear (and incredible) presence of contemporaries like Meret Oppenheim, Leonir Fini, Maruja Mallo, and so many more. Colquhoun’s story is a welcome addition to that Surrealist sisterhood, and a body of work with its own strange sweetness. She was a painter, but she as also a writer and a rebel occultist. Some might have called her a modern witch. Let’s walk around her mind…

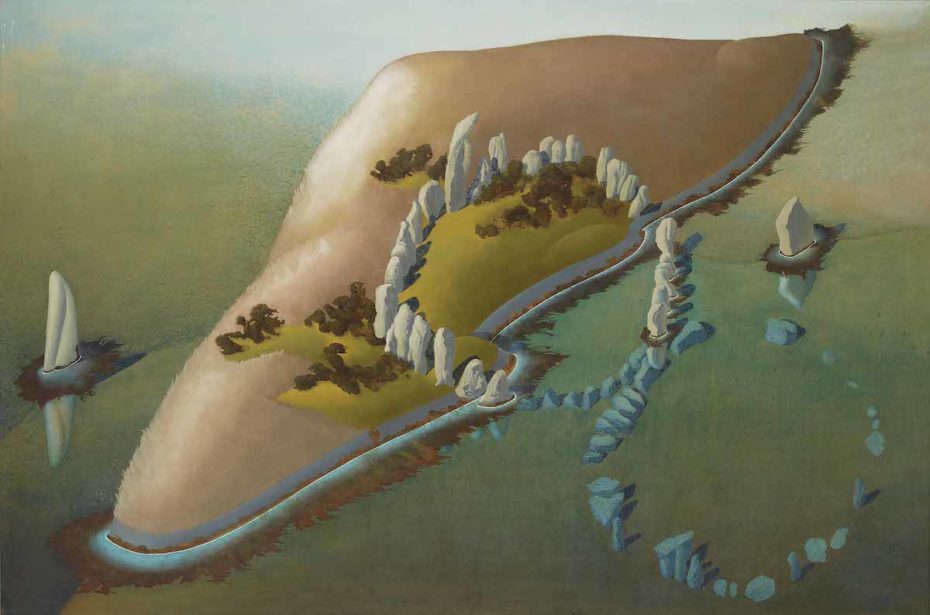

Magritte was applauded for making men float. Dali melted his neuroses, and Yves Tanguy’s dreamlike beaches prompted critics to describe him as one of Surrealism’s unofficial “Druids” – all of which was perfectly on-brand for the Surrealists. Dream analysis, alchemy, and tarot; trance states, séances, and myth creation were all tenants of Surrealist’s “automatism”: an instinctive, esoteric creative process into which Ms. Colquhoun’s work fits perfectly.

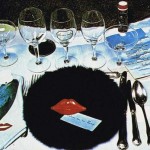

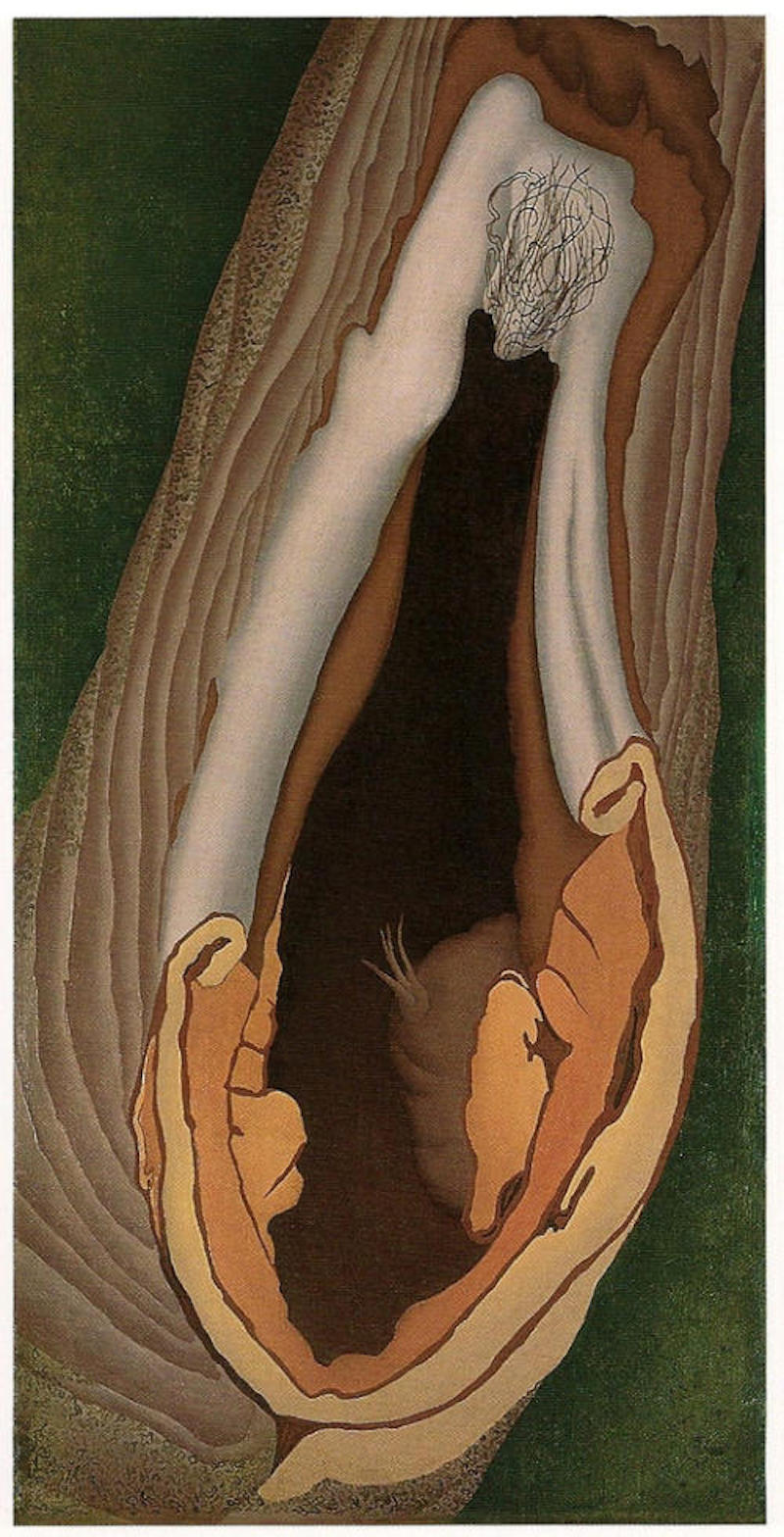

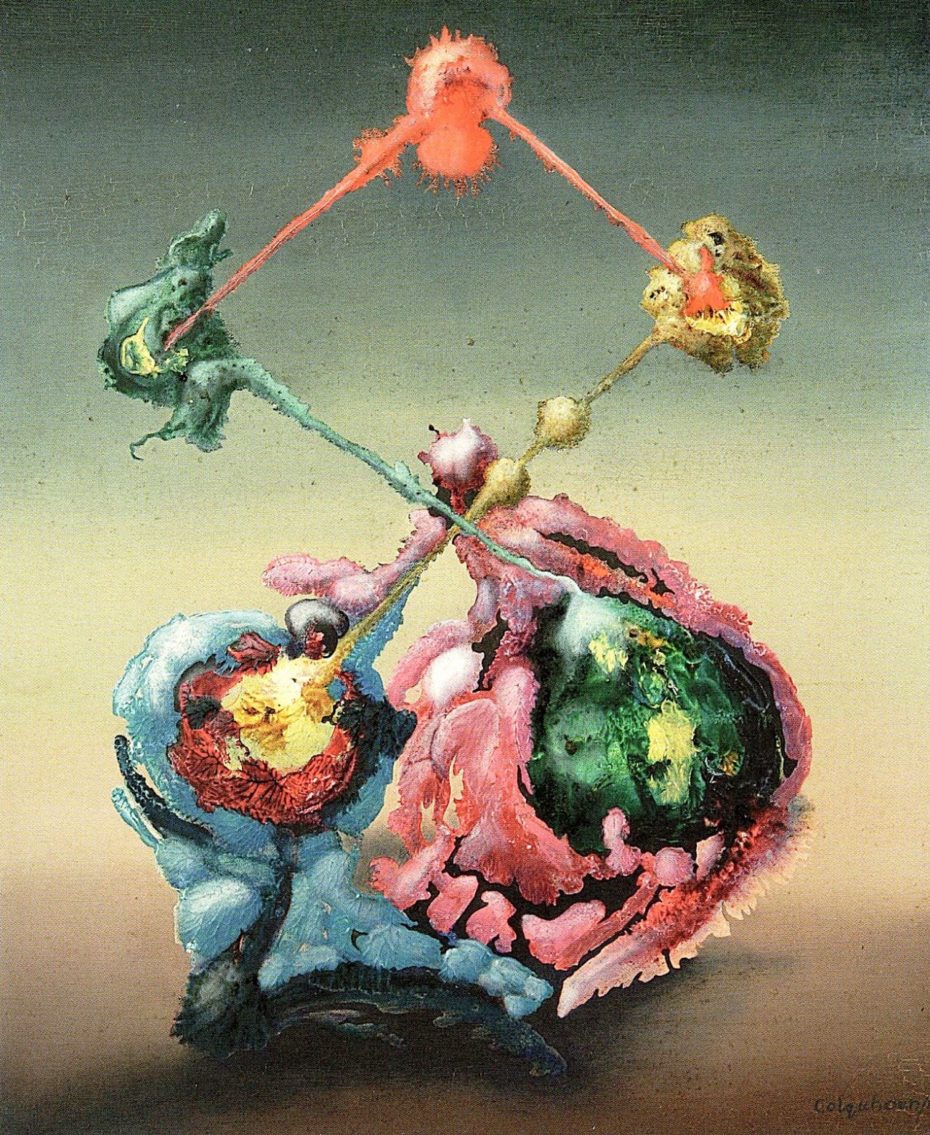

Just look at those juicy globules! They look like microscopic aliens, or Georgia O’Keeffe’s blossoms on acid.

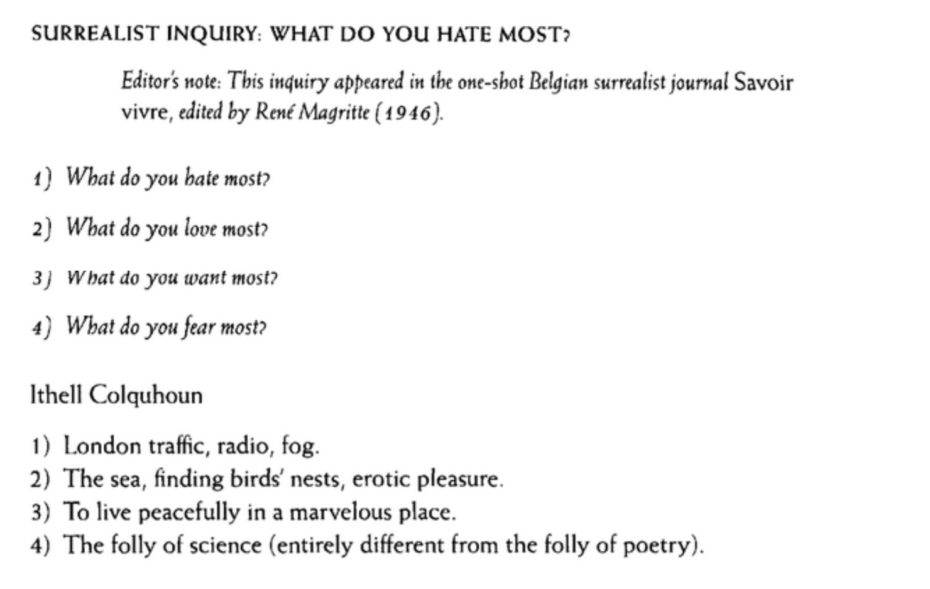

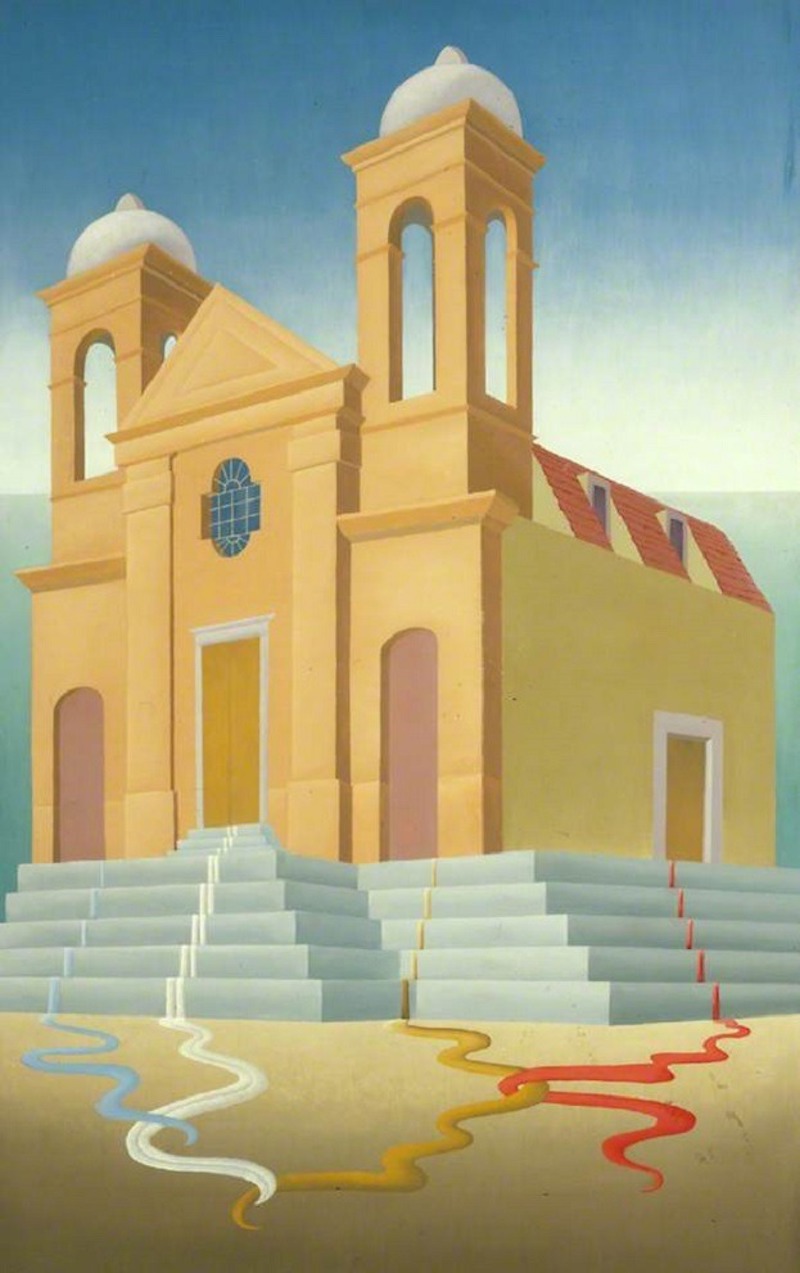

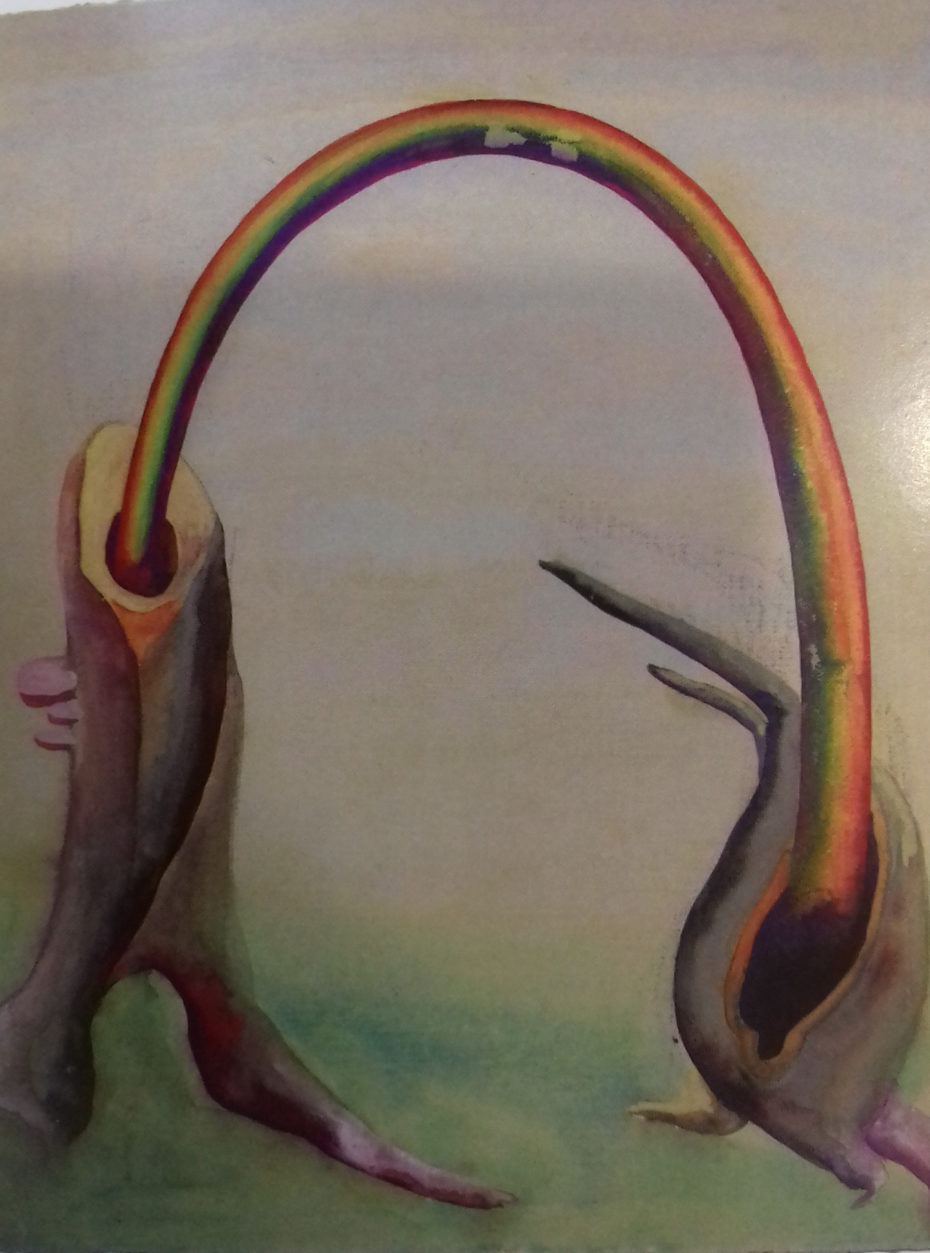

There’s a delicate, thoughtful geometry in many of her pieces – lines that prop up curious landscapes, evocative of both Hilma AF Klimt and Hieronymous Bosch. She called it “psychological morphology”.

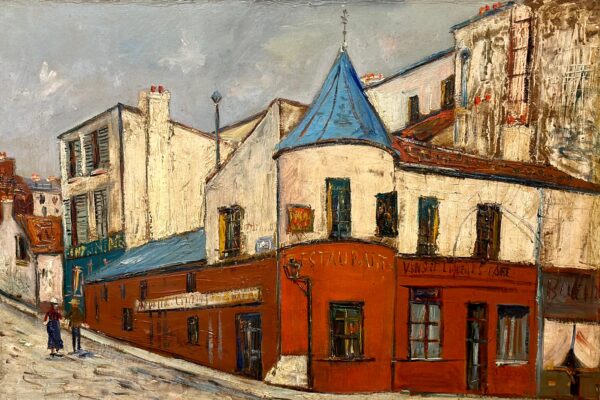

Born in 1906 in (British) Assam, India, Colquhoun moved to the UK as a wee babe and spent most of her life in London and Cornwall, with the exception of some pivotal, character-forming self-exploratory years in Greece and Paris. Think sketching in raw nature, having an affair with a married man, and falling in love with the sensuality of botany and ancient myths.

She attended some formal institutions, but was mostly self-taught – and above all, dazzled by everything esoteric.

Her 1938 painting “Scylla” is a smart reinterpretation of the eponymous Greek monster that feeds on Homer’s sailors. “It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath,” she said of the seascape, which she declared a reflection of her own body, “it is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image.” Methinks Ms. Kahlo herself would approve…

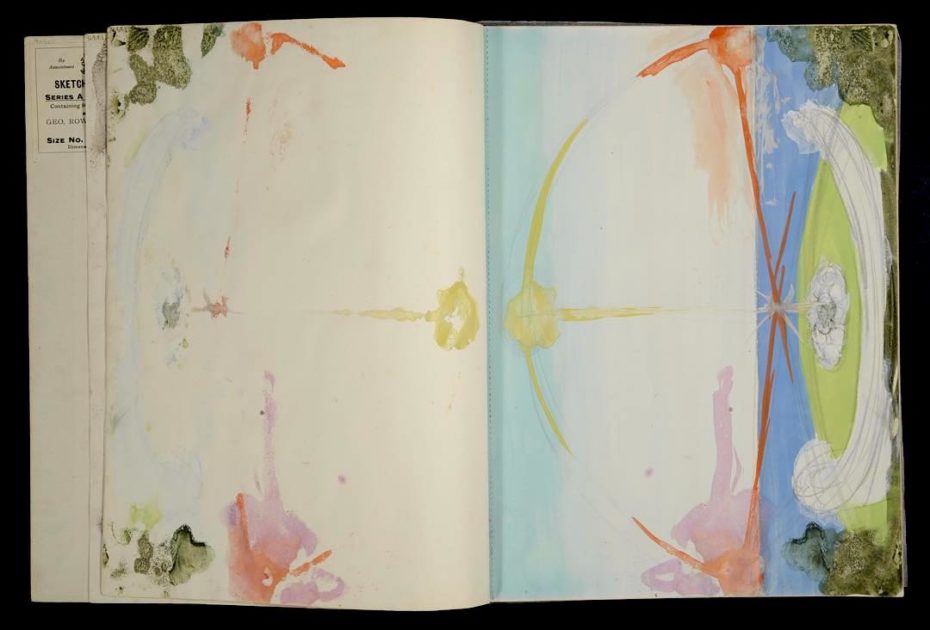

She officially joined Breton’s Surrealist crew the next year, and was a natural fit. She was a groundbreaking artist in the crew, working with techniques like fumage (using candle smoke on paper) and decalcomania or early “decals” (folding paint and prints in paper or on surfaces). She was the also the first to employ entopic graphomania (fancy speak for a freaky connect-the-dots).

And of course, she killed it on the sartorial front. Here she is wearing her beloved “Witch Ball” earrings:

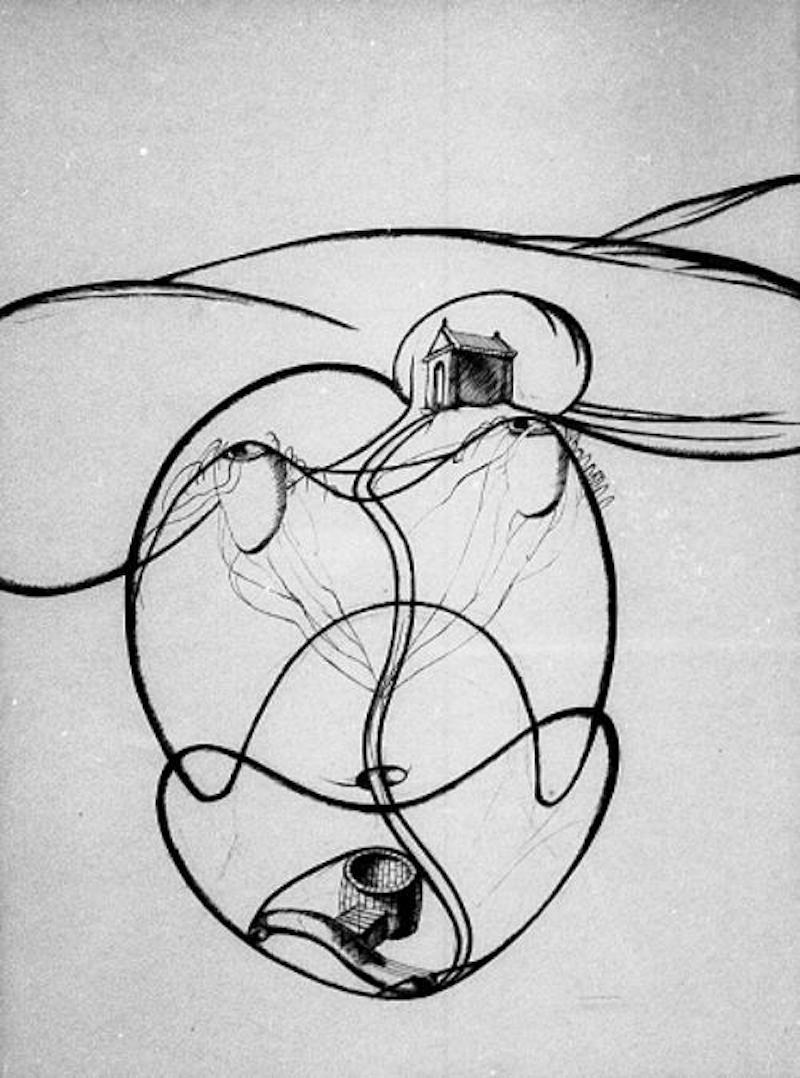

Writing, too, was an essential part of Colquhoun’s artistry. She gave poetry readings in London, and in 1955 published The Crying Wind, a Surrealist travelogue about her time in Ireland and love of Celtic history.

Alas, post-war Surrealism was a toxically insular club that reached a tipping point. Even the critics of the 1947 exhibit said as much, calling it a “last hurrah” for the crew when the show proved lackluster. Perhaps Colquehoun’s departure, just a year after joining, was prophetic of that decline.

When the artist showed interest in joining multiple occultist societies, Surrealism’s founders, André Breton & co. gave her the boot. So she said au revoir to the boy’s club and started learning from the Ordo Templi Orientis, and the Golden Dawn splinter group “Stella Matutina.” Life carried on – and in magical fashion.

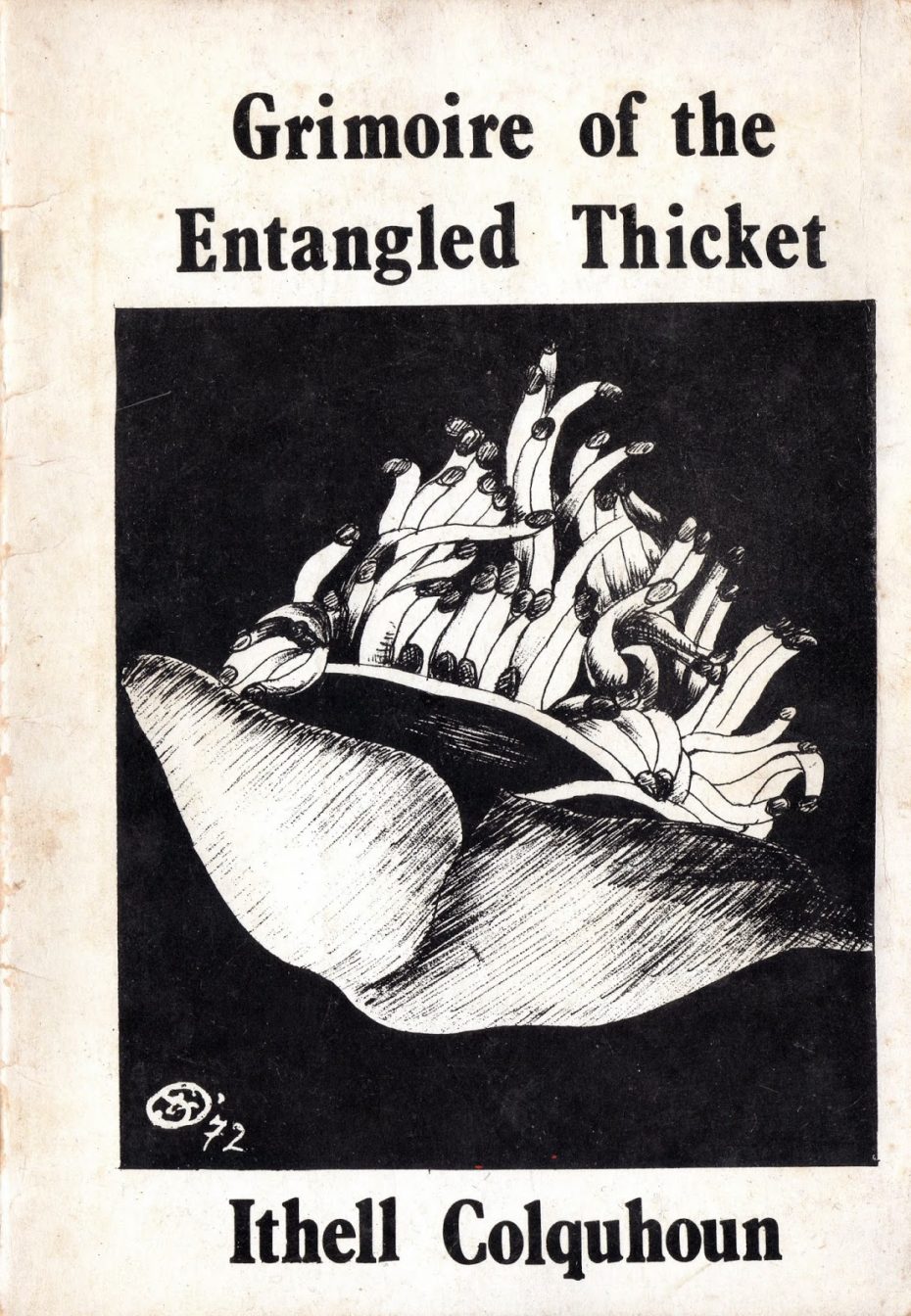

She continued to paint, and published unusual illustrated literary works like The Goose of Hermogenes (1961) and Grimoire of the Entangled Thicket (1973), a collection of poems that blended her particular brand of pastoral Surrealism with the tradition of “automatic” (or impulsive) writing.

have fled as a chain, I have fled as a roe into an entangled thicket, I have fled as a wolf cub…

Ithell Colquehoun, Grimoire of the Entangled Thicket

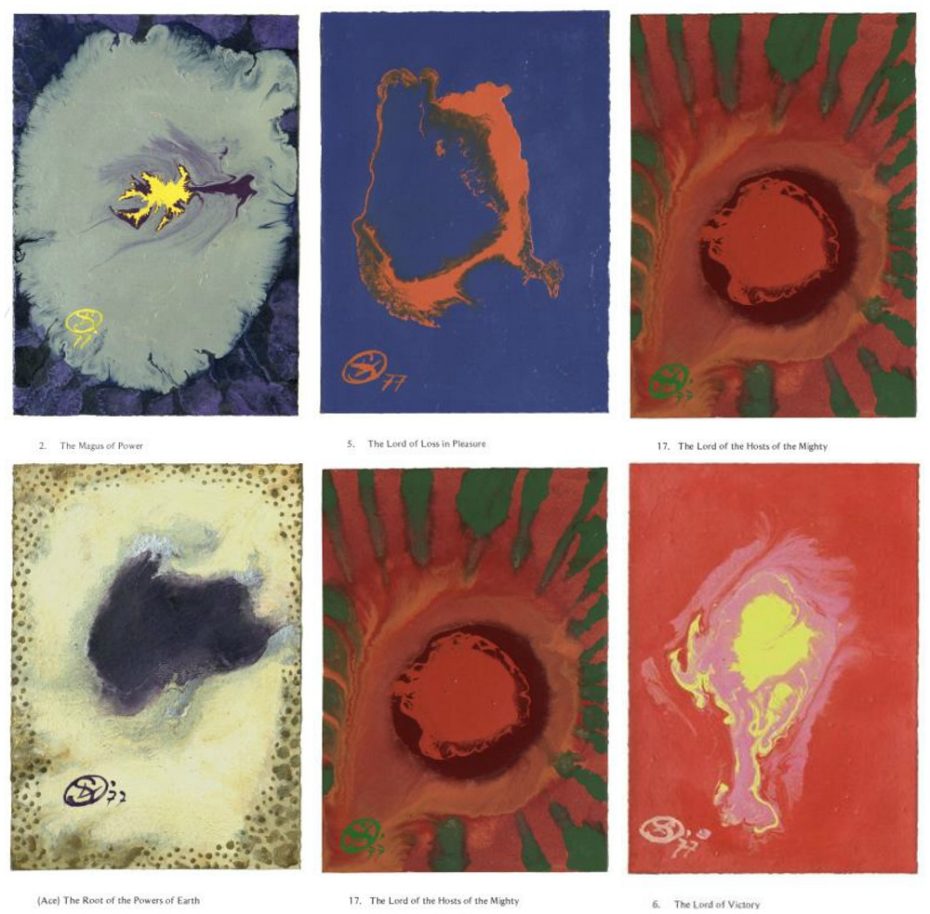

Decad of Intelligence was another late-1970s series of 10 paintings and corresponding texts exploring the Kabbalistic treatise, Sefer Yetzirah. (And quite a handsome holiday gift, if you ask us):

We mortals are lucky that Colquhoun lived into the 1980s, as she’s left behind a trove of images and words – some, more Surreal than others – for us to dream about. She tackled everything from classical tropes, like her 1929 take on Judith beheading Holofernes:

She was also right at home in the psychedelic cultural turn in the ’60s-70s, a time in which she adopted a new name, Splendidior Vitro. A Surrealist, if you will, who successfully jumped the weathered the growth from pre-war, to post- and beyond. Goddess knows she turned out a delightful tarot deck:

It wasn’t that she didn’t want to commit to the Surrealists. She just refused to put a cap on her personal and artistic growth, and it’s delightful to see the alchemy of that autonomy evolve on canvas. “Her name and reputation is little known but it deserves to be,” Tate archivist Adrian Glew told The Guardian in 2019, “She had very few solo exhibitions.” Luckily for us, the museum acquired more than 5,000 works by Colquhoun, big and small, that very year. Hopefully, we’ll be hearing more about Colquehoun in the future – and we certainly have a post-lockdown museum day to look forward to.

Ring up our favourite indie booksellers to order Ithell Colquhoun’s writing.

About the Contributor