An artist like Erté was unlikely to go by unnoticed in history with his profound obsession for the arts, spanning from dance to theatre and film to high fashion and beyond. The visual wizard arguably coined the Art Deco aesthetic with a signature style that continues to inspire modern design today and yet, his name remains somewhat buried amidst the roster of history’s greatest artists…

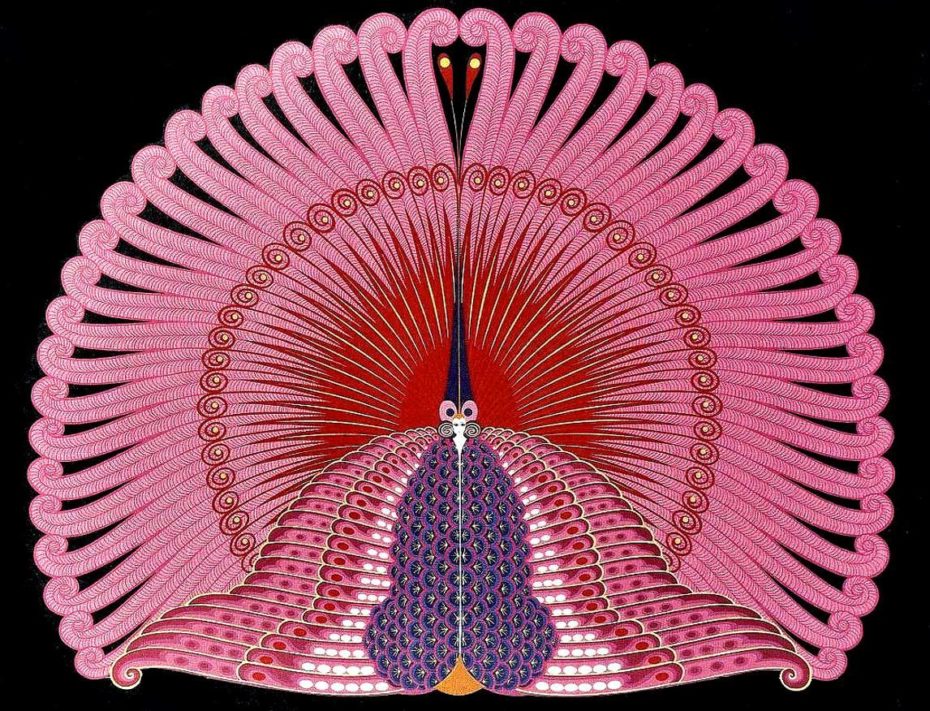

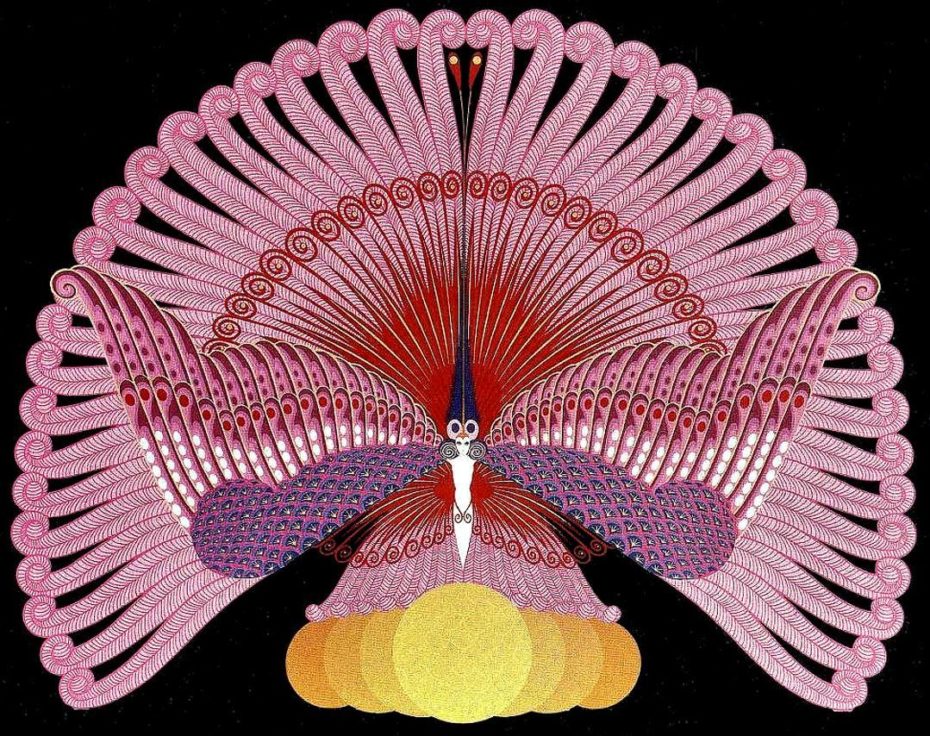

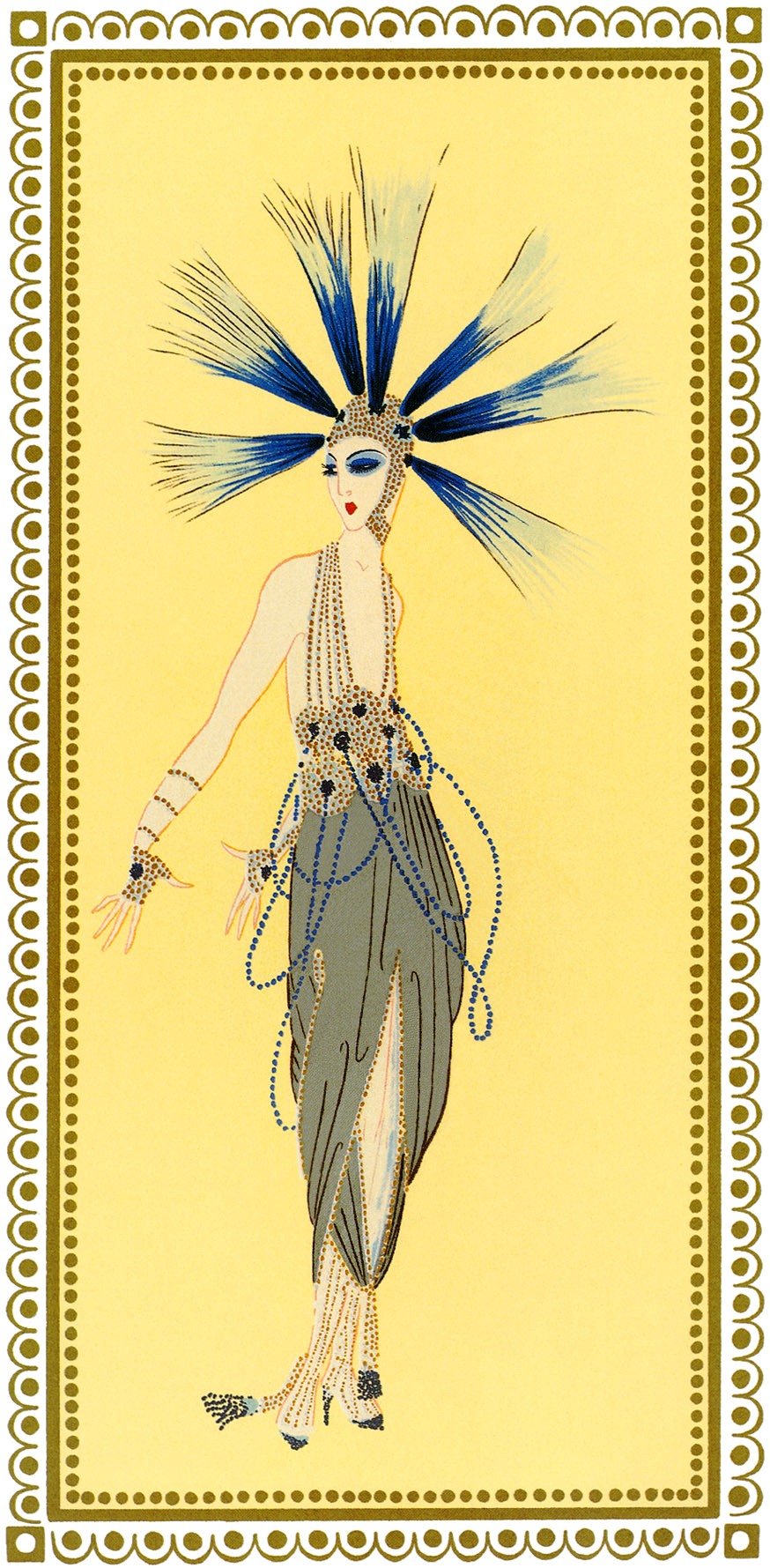

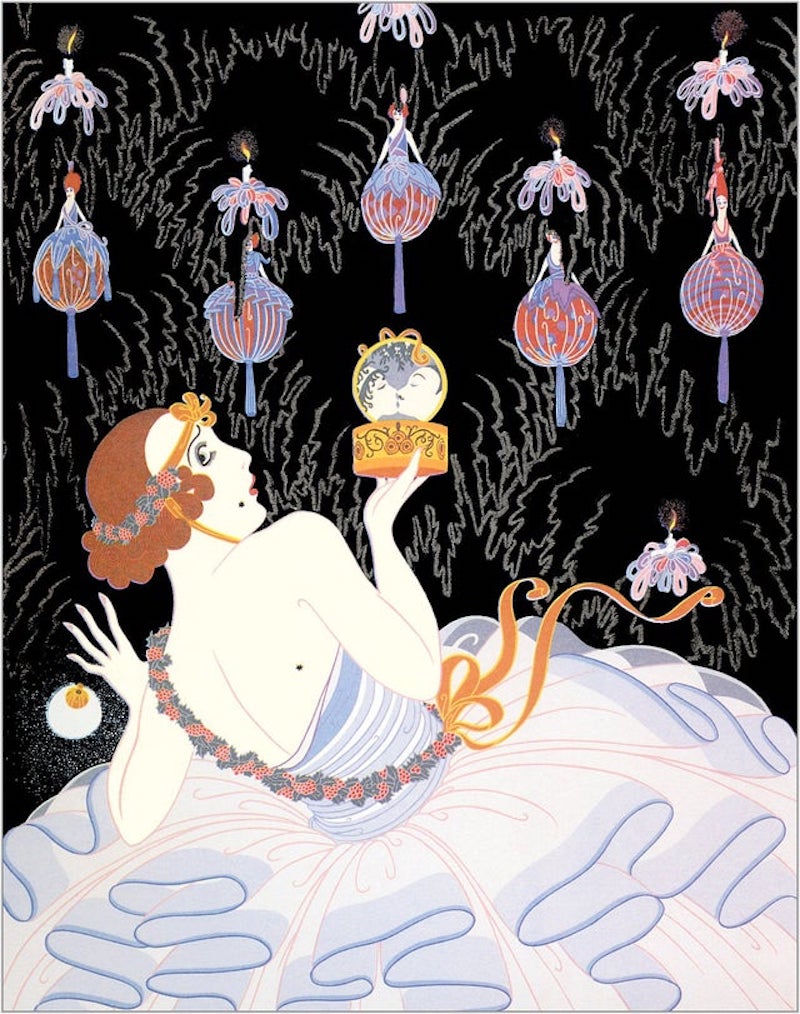

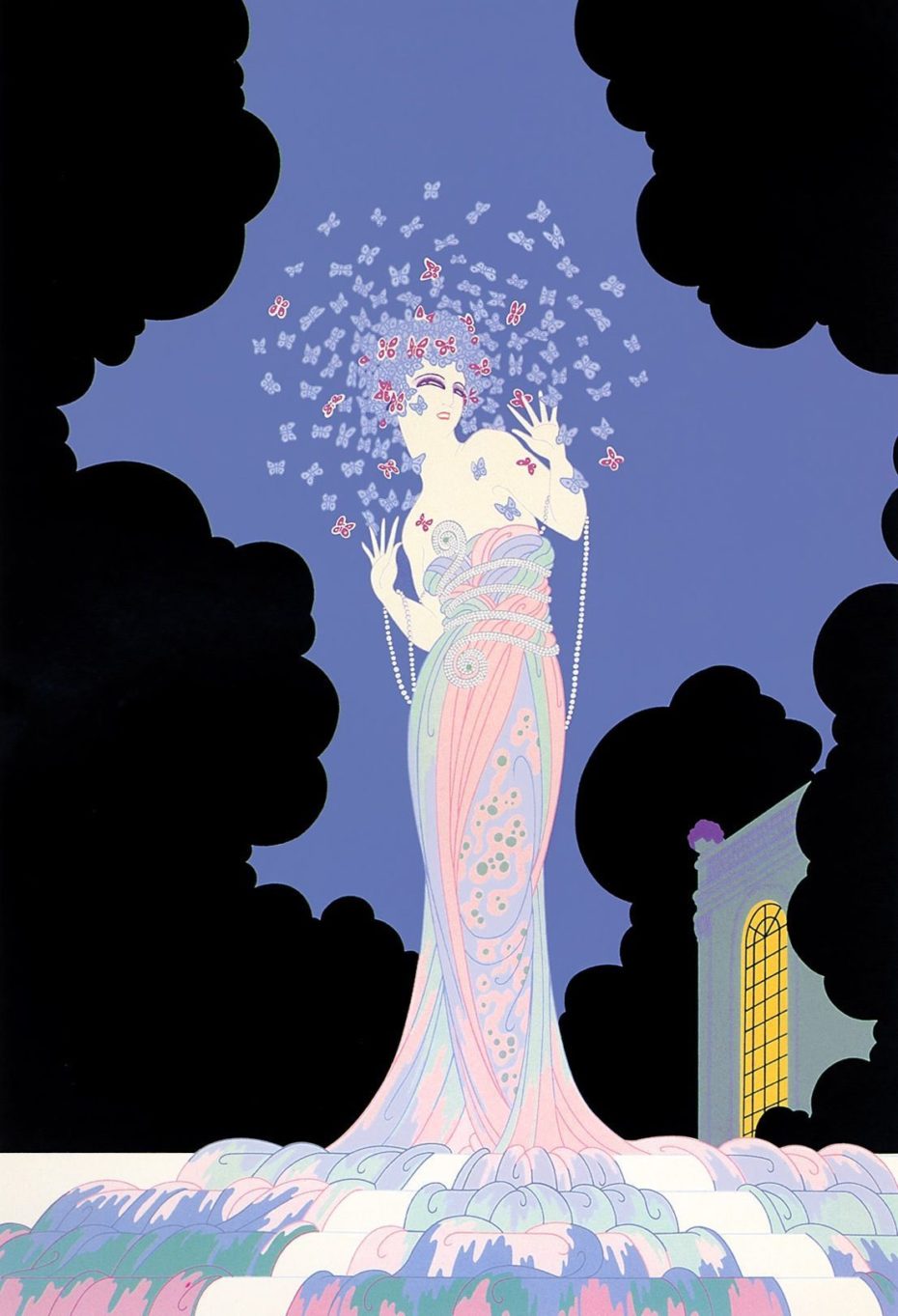

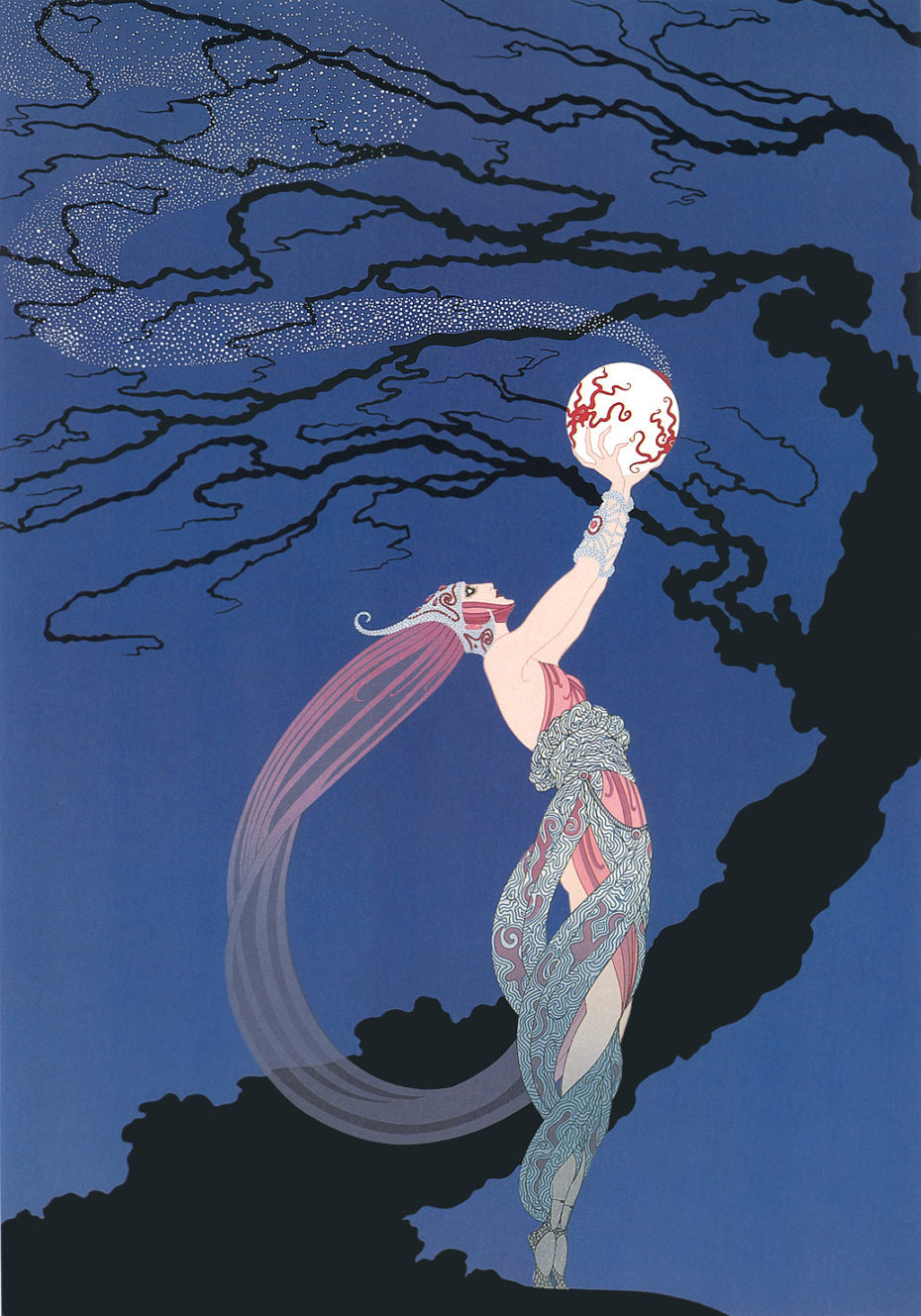

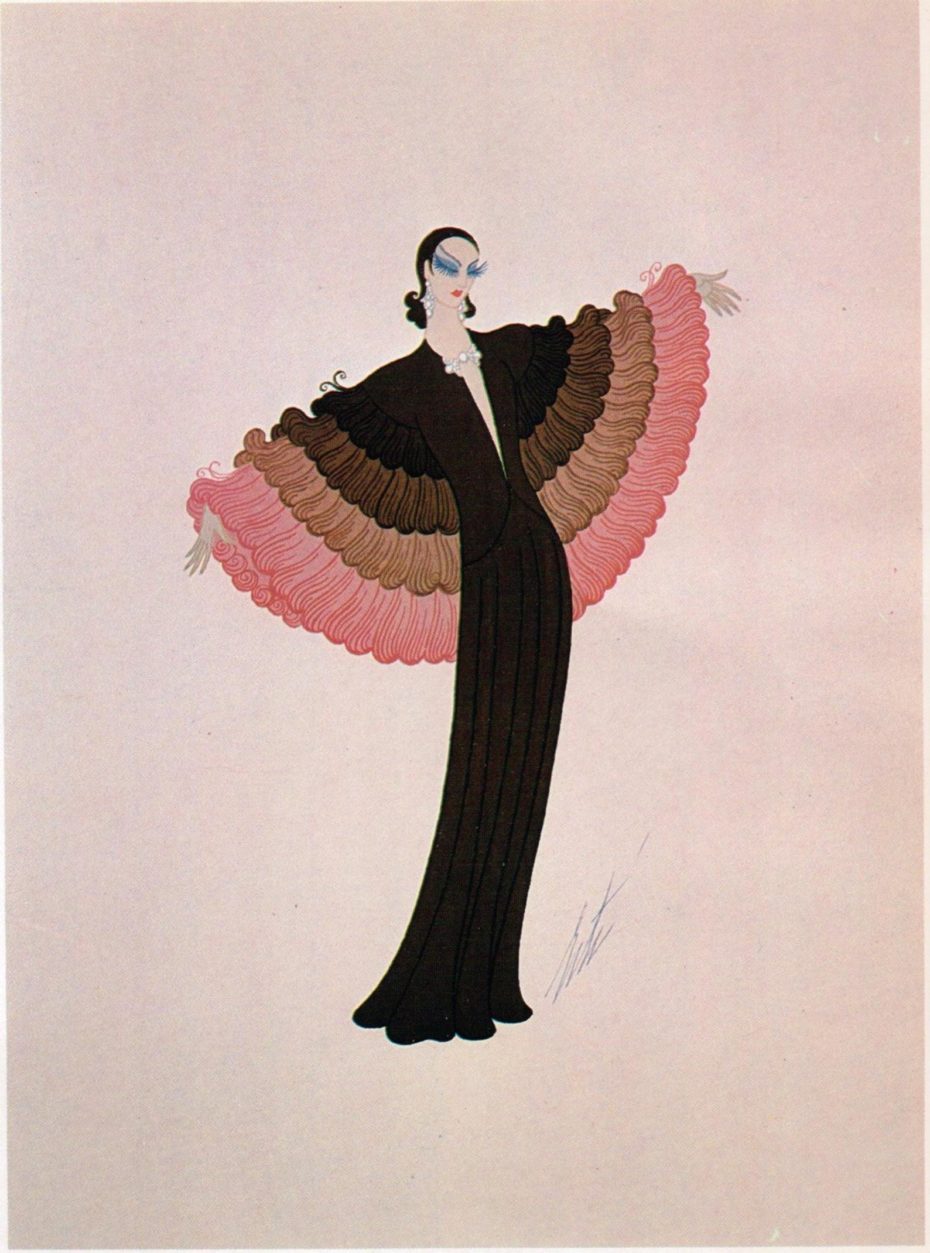

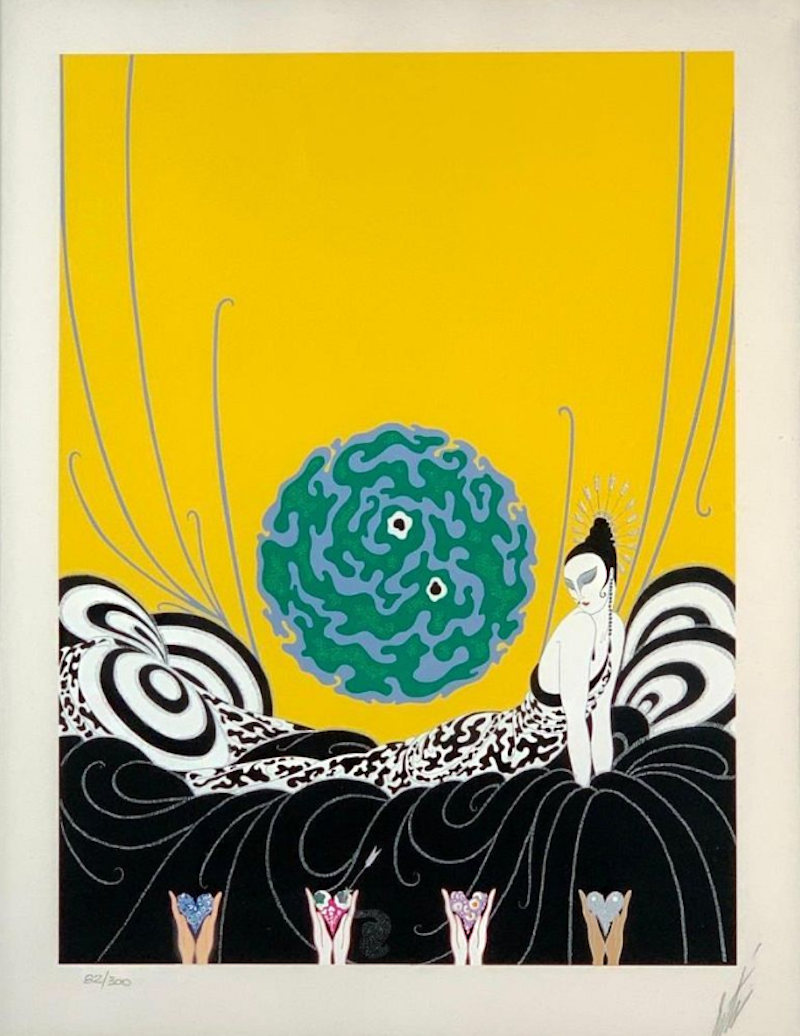

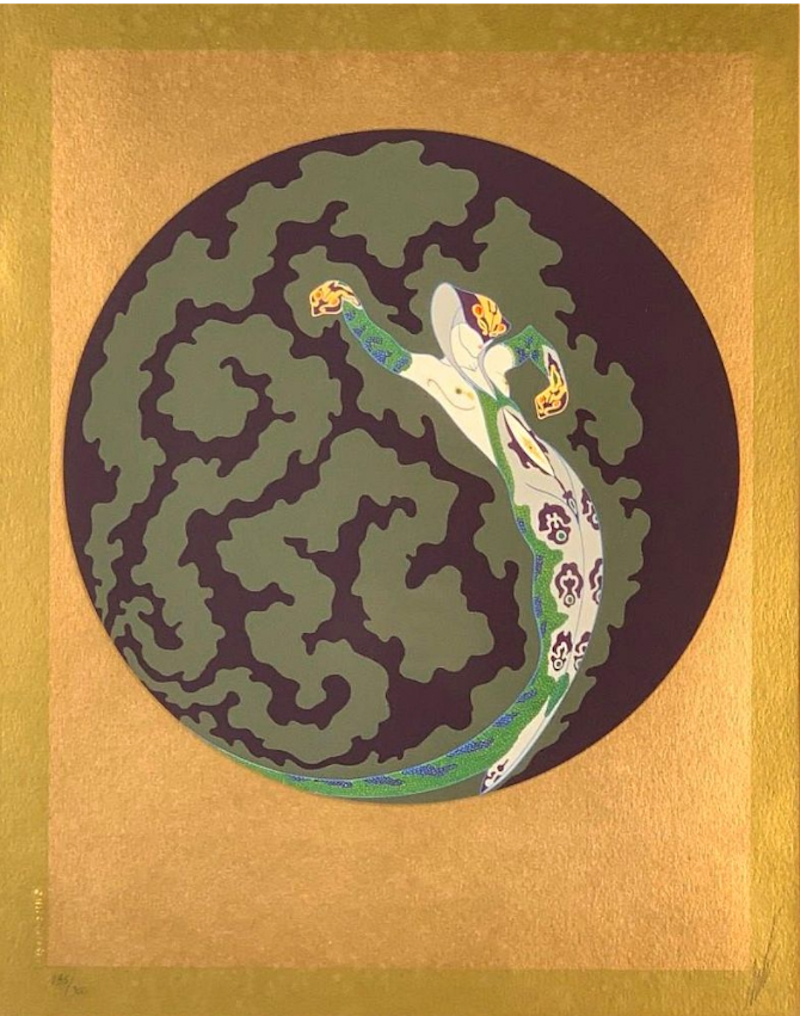

Art Deco is characterised with a general sense of extravaganza, cultural melding, draped elegance, vibrant patterns and textures. Erté is then the godfather of the movement giving it both an initial push and reviving it towards the end of the century once again. Today, he continues to inspire countless artists, designers, and style icons, sometimes even unknowingly, by having paved the whimsy of modern design in all its forms.

By the age of five, Erté, born Romain de Tirtoff, had already designed an evening dress for his mother. He was raised an aristocratic family in Saint-Petersburg, Russia, where his days were filled with cultural sightings at the Mariinsky theatre. He was in the audience the night that Nijinski, ballet’s greatest male dancer, was fired for scandalously appearing on stage in his tights without a jockstrap to protect his modesty. Romain flirted with the idea of becoming a dancer himself but came to the conclusion that “I could live without dancing, but could not give up my passion for painting and design.”

In 1900, he visited the Paris Exposition Universelle as a young boy; and by 1912, not yet twenty, Romain had moved to Paris as a correspondent for a Russian magazine “Ladies World”. While sketching models for fashion houses, he found himself another job with a small couturier “Carolyn”, but his unbridled imagination proved too eccentric and the young designer was quickly let go and advised: “Young man, do anything in life, but never try to become a costume designer again. You won’t get anything out of this.” Offended but not discouraged, Romain de Tirtoff would soon find a kindred spirit in the turn of the century’s most prolific couturierm Paul Poiret.

Poiret, who was already regarded as the King of the fashion world by the time their paths crossed, played a critical role in Romain’s early career, even assigning him the pseudonym “Erté”. Poiret’s exotic world more than appealed to Tirtoff. The shows, the colours, and the magic that he saw in Russia, the newly-christened Erté knew that he could push way beyond the borders in Paris — and he did.

Late critic Brian Sewell writes in his essay that Erté, “he brought theatre into the field of fashion.” His experience, after all, was one rooted on the stage and he refused to bow his designs to everyday life. Instead, he brought everyday women to the stage. He never liked working with conventional classic beauties, and said he always preferred women with “certain defects” and unique attributes that he could highlight.

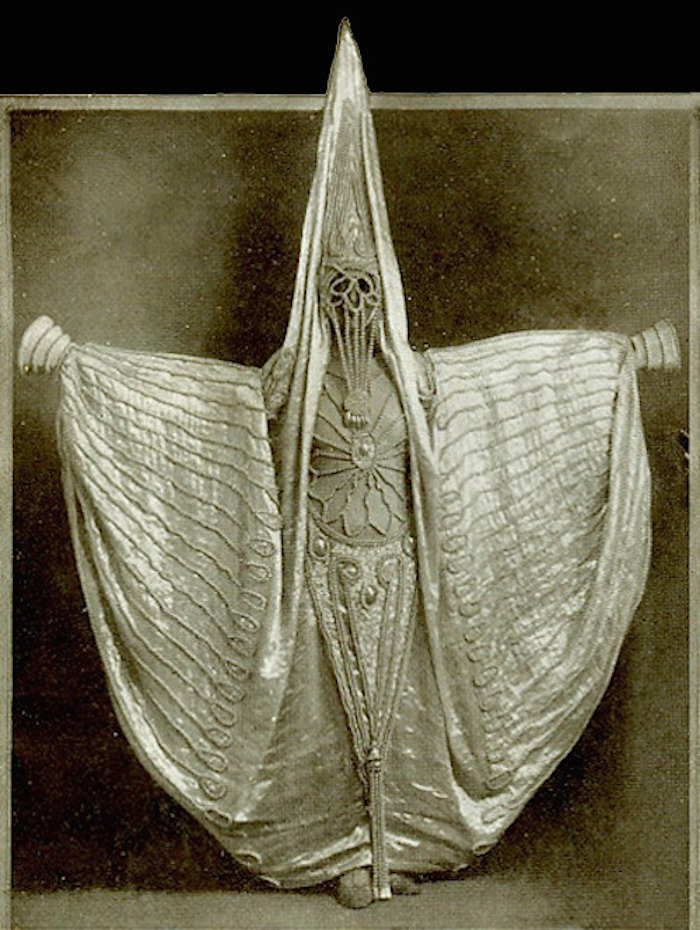

One of his greatest muses was Italian heiress and patroness of the arts, Marchesa Luisa Casati, who emerged as the brightest celebrity style icon in early 20th century European society. Tall and elegant with flaming red hair and unnaturally large green eyes, she was frequently dressed in eccentric get-ups designed by Erté and carried herself in a manner that was absolutely scandalous for her time. Unbeknownst to many, the Marchesa is possibly the most artistically represented woman in history after the Virgin Mary and Cleopatra. The original Lady Gaga if you will, her influence, propelled in large part by Erté, is all around us.

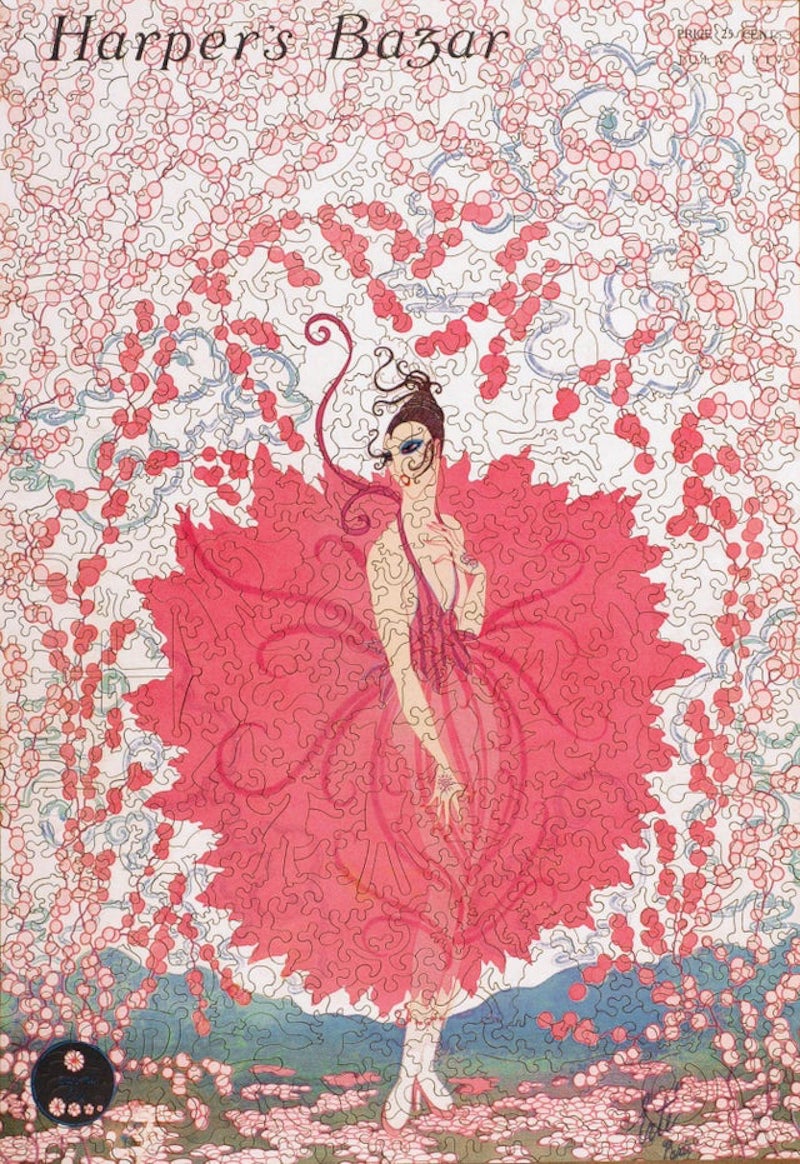

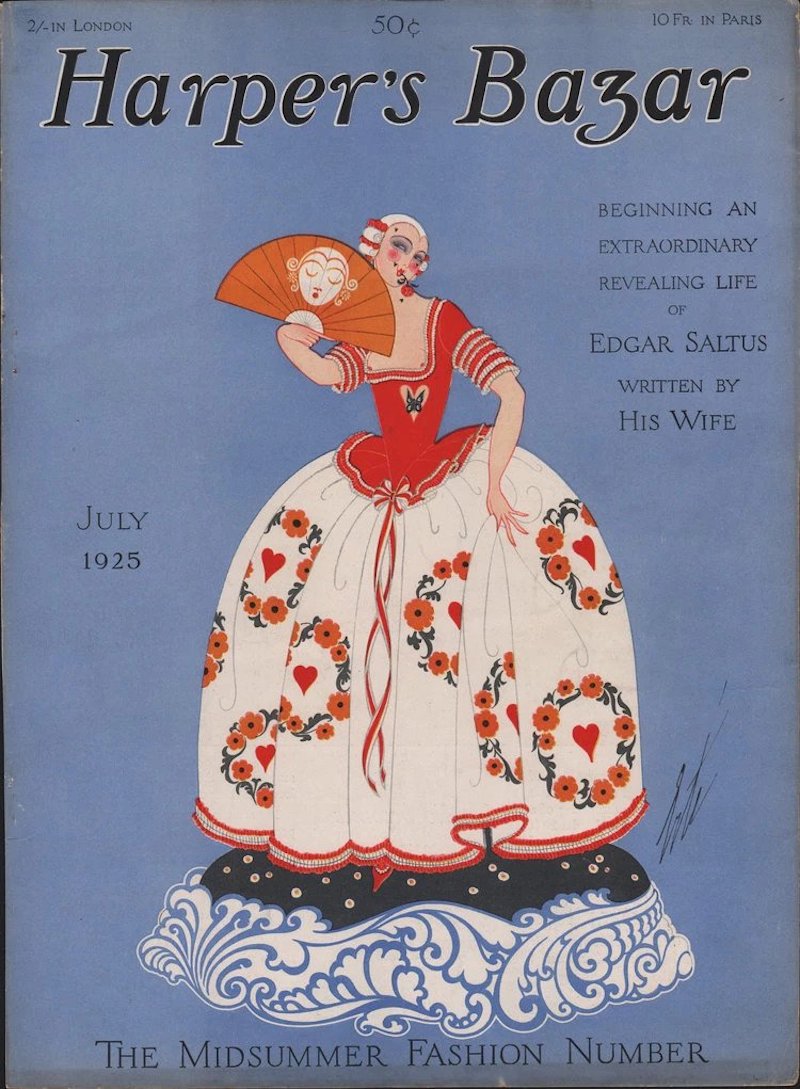

As World War I broke out, Erté had to seek financial stability stateside and thus started his long-standing relationship with Harper’s Bazaar magazine. He owes much of his initial popularity to the publication which he worked with for 22 years. It was there that he designed more than 240 magazine covers and took charge of America’s artistic direction for two decades. Harper’s Bazaar was the perfect medium to introduce American society to his newfound artistic freedom in Western Europe and today his covers can sell for thousands of dollars at auction.

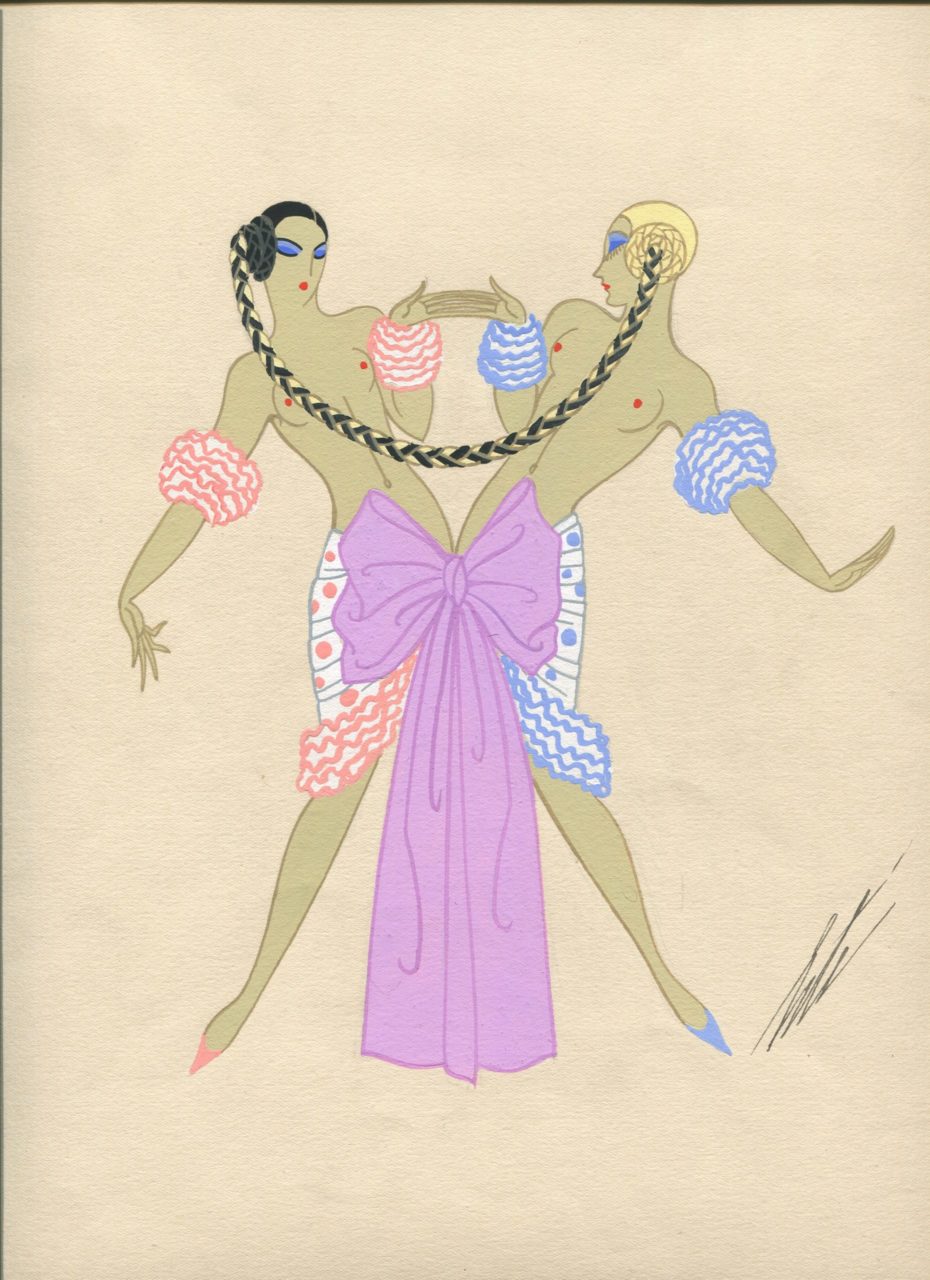

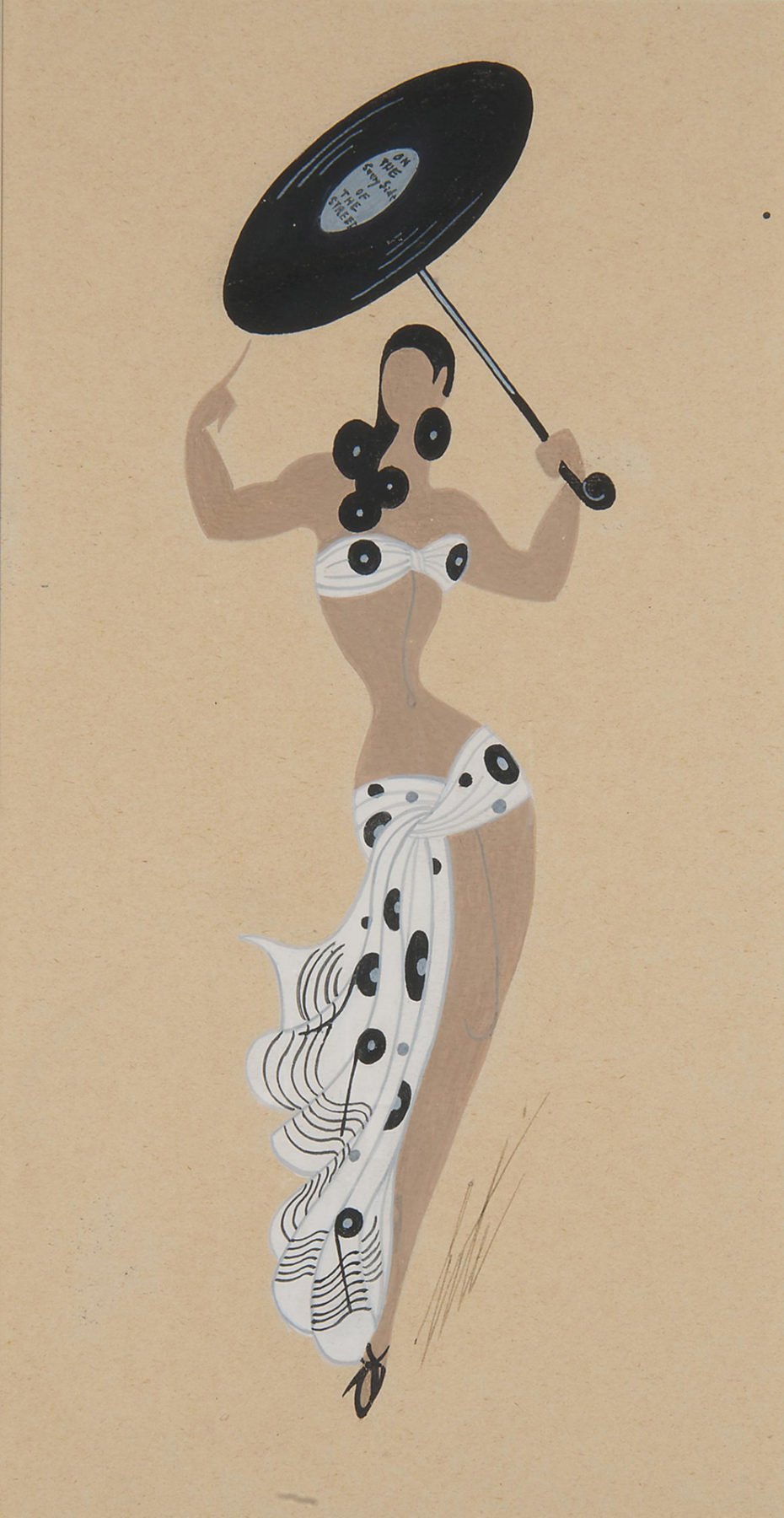

Seeing the limitations of couture fashion, it was during the Jazz Age that Erté then took on another feat where his imagination could really go wild: ballet and theatre.

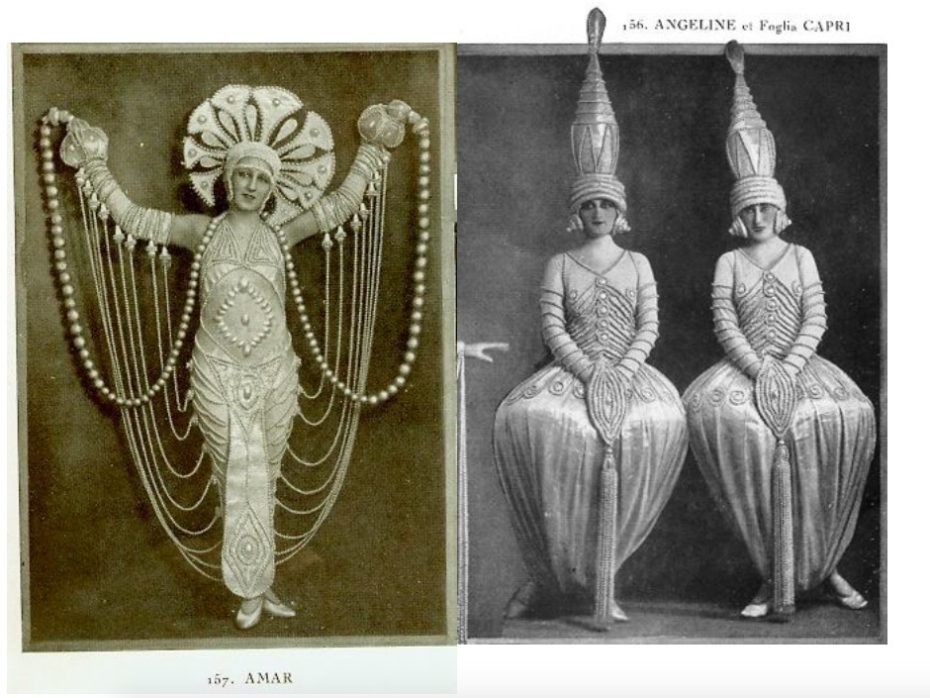

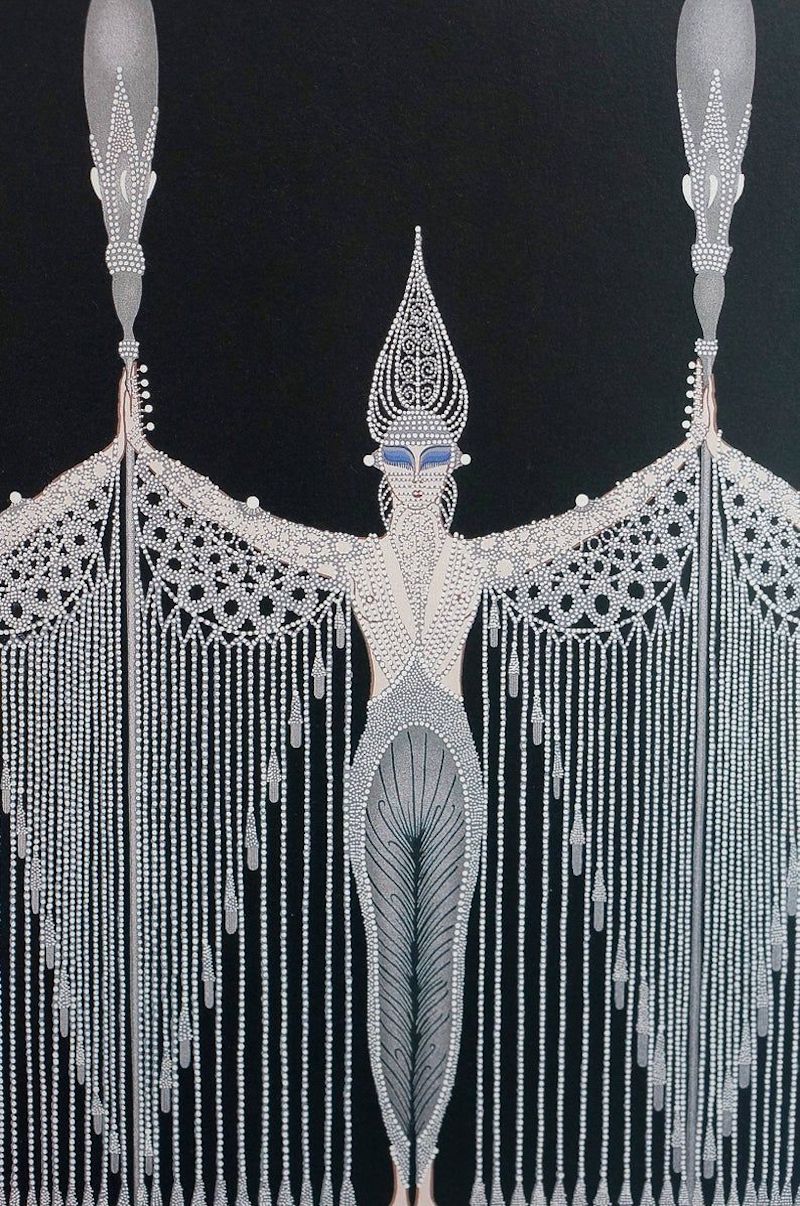

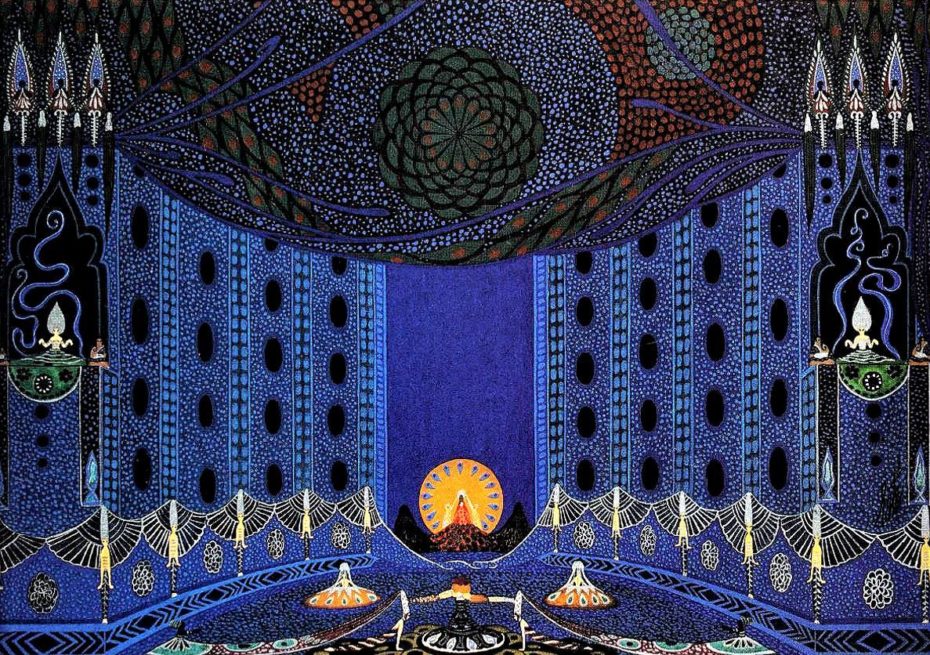

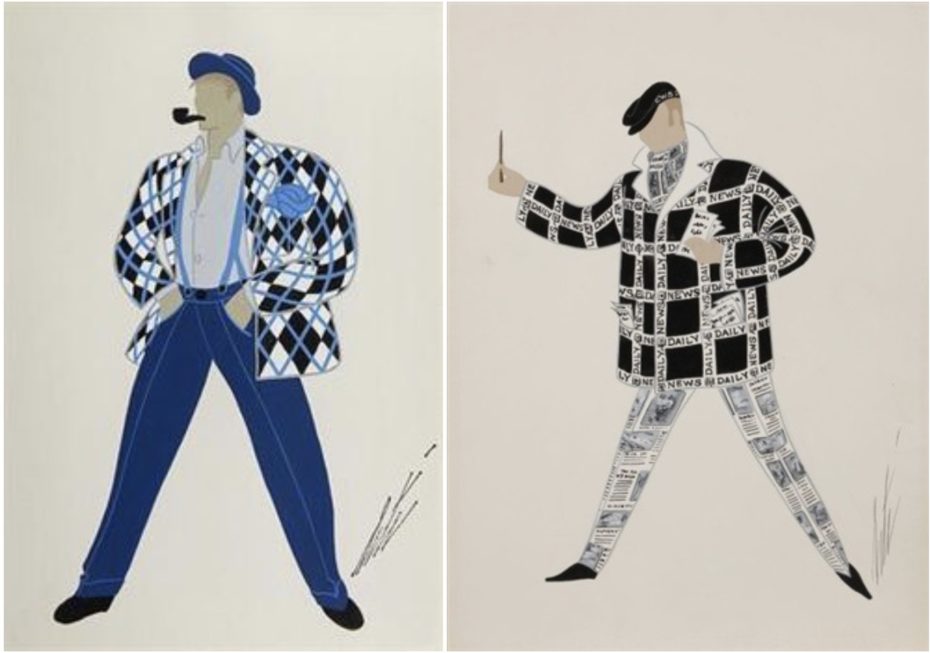

His costumes, programme designs, and sets also graced the stages of Broadway at the Ziegfeld Follies of 1923 and Paris’ renowned Folies-Bergere starring Josephine Baker. Presenting women as superwomen, adorned in futuristic fashions, vibrant colours and fantastical textiles, “imagination,” he said, “is the main thing in my work. Everything I have done in art is a game of imagination. And I have always had one ideal, one model – dance movement. ”

Men’s fashion was not off limits either – reintroducing velvet, silk and brocade fabrics that hadn’t been seen on men’s suits since the 18th century, and were unthinkable for the masculine aesthetic at that time…

Erté produced over 22,000 designs throughout his career, crossing over into several mediums including interiors, sculpture, accessories, jewellery and even cuisine. In 1930s Paris, he created an “Erté dessert” for a famous brasserie; a decadent and mountainous composition of exotic blue strawberries. He also dappled in the movies, designing the costumes and sets for classic films of the 1920s like Ben-Hur, The Mystic, and The Restless Sex.

In the 1970’s and ‘80s, Erté unearthed Art Deco once again with his “Numbers” and “Alphabet” limited-edition prints. These became a “must have” for all fashion aficionados. He encapsulated diverse aesthetics including Russian iconography, Byzantine mosaics, Greek pottery, Indian and Egyptian art, high Parisian fashion and the theatricality of Parisian cabarets – and his experience with design gifted everyone a piece of wonder.

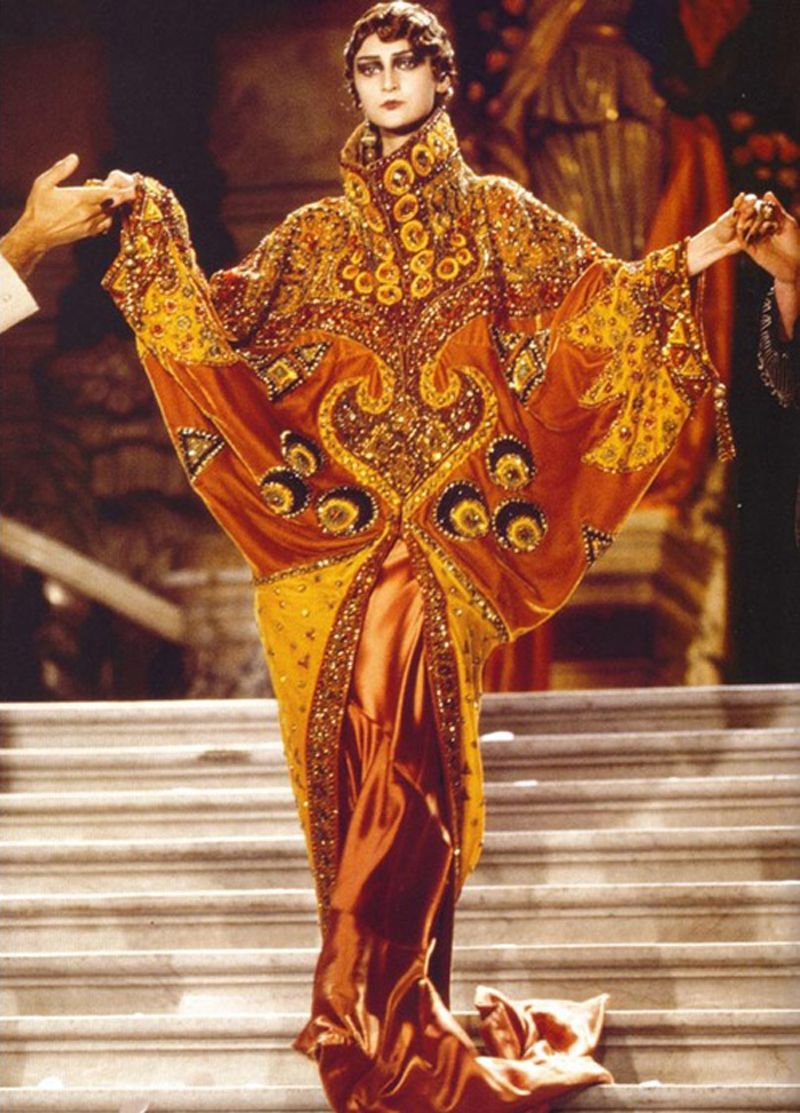

In 1998, the house of Dior under Galliano dedicated its Haute Couture collection was an indisputable ode to Erté, his mentor Paul Poiret and their 1920s muse, Luisa Casati. Similarly in 2010, Karl Lagerfeld’s resort collection for Chanel sent Casati lookalikes down the runway dressed in silvery gowns heavily-inspired by looks Erté had designed for the eccentric heiress.

Ever impeccably dressed in tailored suits, and often photographed at home in Paris with his beloved cats, Erté and Karl Lagerfeld in fact, both maintained a very similar persona of the elegant yet eccentric dandy.

Think of Cher and her Bob Mackie moments in the seventies and it’s hard not to see Erté’s influence too. Other designers like Oscar de la Renta and Marchesa have forever changed their manner of designing by adopting Erté’s draping technique and sustainable fashion militant Stella McCartney most recently featured the designer’s signature motifs in her 2020 collection.

Erté’s distinguished career spanned over 80 years, and when he died at the age of 98, naturally, he had already designed his own funeral invitations, as well as a mahogany coffin which was decorated with Art Deco floral wreaths. His was such a characteristic style, Art Deco as we know it today, that it set a backdrop for the entire 20th century. In a sense, he changed the way we view fashion today: a performance of art rather than an everyday trifle. As a fashion magician of sorts, the value of Erté in the world of style and art is no doubt, immeasurable.

About the contributor