We have all heard of the Beat Generation, but have you been keeping up with the Kardomahs? Across the pond from Ginsberg’s gang and a couple of decades earlier, there was a group of bohemian artists and writers who beat them to it. The Kardomah Gang are Wales’ and the world’s forgotten intellectual boyband, who are remembered more for their careers as solo artists. Today, let’s dust off their back catalogue, work through the early years and together unearth a rare b-side, called ‘the lost café culture of the 1930s’.

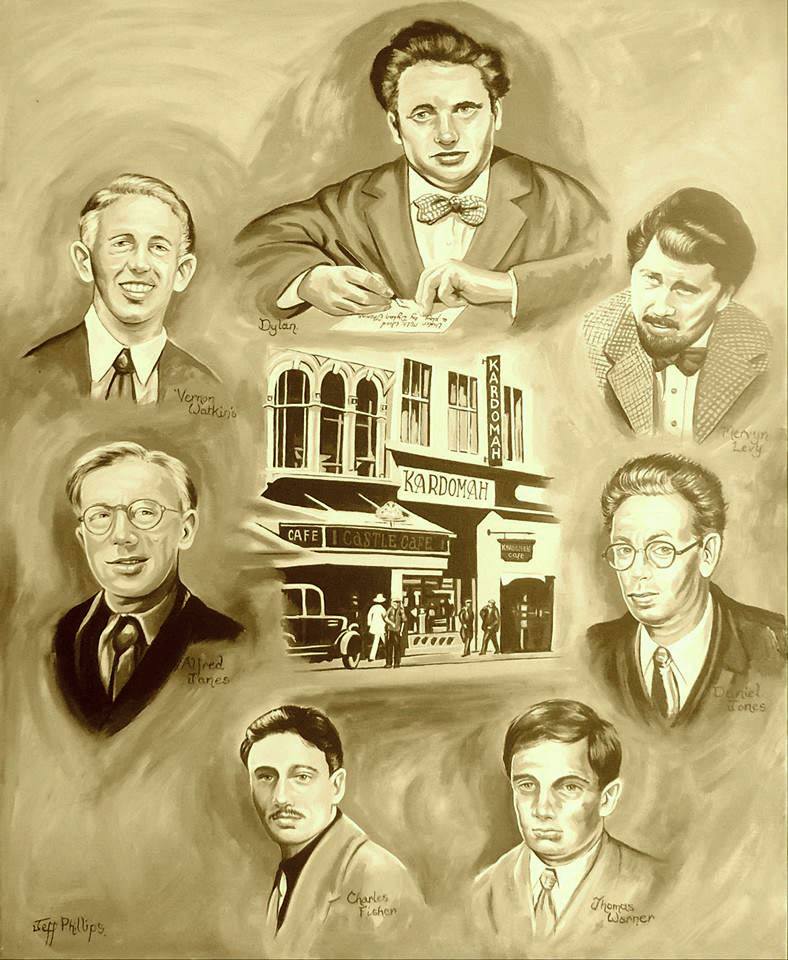

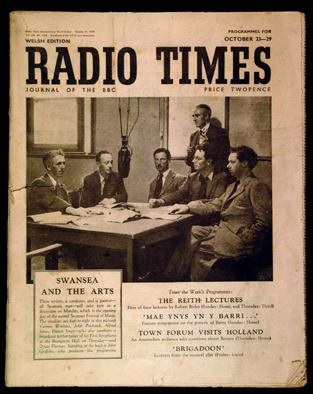

The Kardomah Boys’ main man was Dylan Thomas, a young newspaper reporter at the South Wales Daily Post who would go on to be one of the most important poets of the 20th Century, or as I like to call him, the Harry Styles of the group.

Fellow future poet Charles Fisher was working as a journalist at the same paper during the early 1930s. He and Dylan bonded over spoof thriller literature and would stretch out their lunchbreaks writing drafts in the cheap and cheerful café opposite their office in Swansea. Charles’ Dad was the head printer and ‘overlooked the long absences from the newsroom’, so the pair of slackers got away with it.

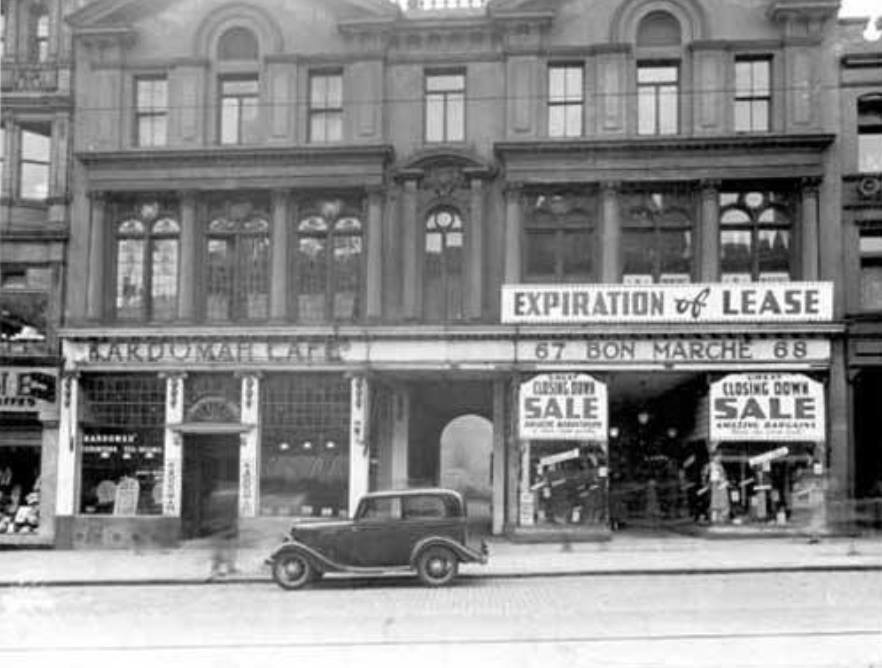

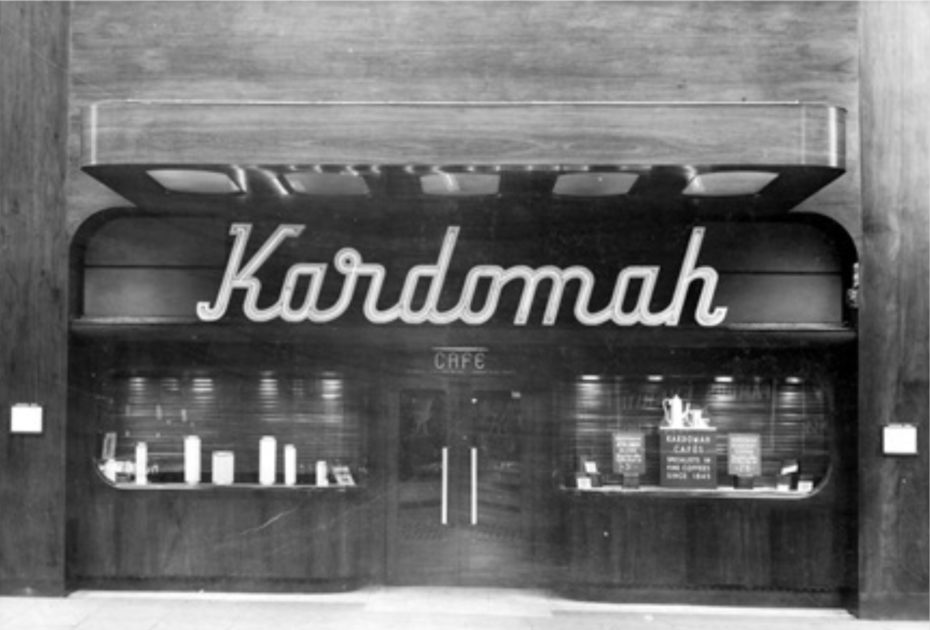

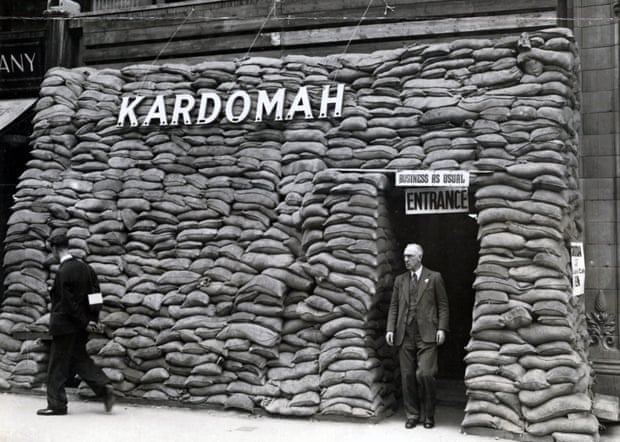

The Kardomah café was not your regular greasy spoon, it was a hip hang-out for Swansea’s bohemians to be and be seen. It successfully fashioned itself as an upmarket yet everyday place for customers to lounge as long as they liked, all for the price of one coffee. The waitresses there didn’t simply serve coffee, they caffeinated the conversations of their own Lost Generation.

People from all walks of life, who perhaps didn’t feel welcome in other establishments, came to eat good food, smoke, ponder life, drink, and listen to live jazz. Just like today, coffee shops in the 1930s became the perfect places to find your pen-chewing tribe, watch the world go by, or put that big idea on paper, regardless of whether you’re a dreamer or a doer.

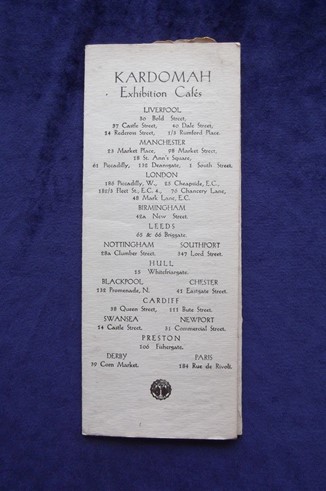

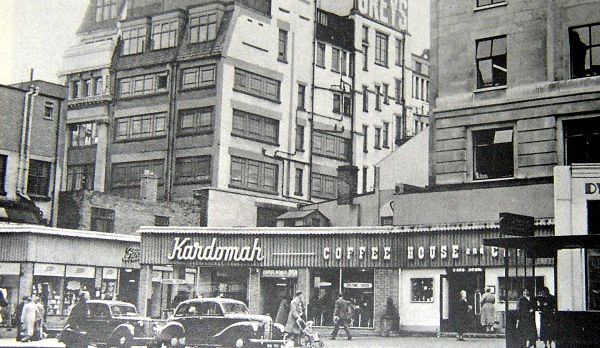

Around 20 UK towns and cities saw Kardomah cafés pop up on their high streets. Think of them as the Starbucks of their day, but family-run, with nicer coffee, a bohemian spirit, better food, string quartets, stylish interiors, less evil… ok, scrap that. Let’s say, the Kardomah cafés were what coffee chains should be.

The more time Dylan and Charles spent nursing their cold coffees at the Kardomah café when they should have been working, the more local bright minds they met. This included poet and translator Vernon Watkins, composer Daniel Jones, Marxist scholar Bert Trick, and artists Alfred Janes and Mervyn Levy, amongst others. This wasn’t a case of a manufactured boyband line-up reshuffle, the group changed shaped naturally, depending on who took a seat at their table that day. ‘We had no manifesto to publish, no theory of art to propose’ said Charles, ‘we were all too individualistic for that’. The informal nature of the group suited their informal regular meeting place, and so they gained their name and a reputation as a collective, whether they liked it or not.

‘Kardomah – My Home Sweet Homah’, was the name Dylan gave to the café where they put the world to rights. The Kardomah comrades would sit and air their big fish small town blues and dream about the bright lights of London and New York’s literary scenes. Nothing was off the table, the group would ping pong from ‘Stravinsky and Greta Garbo’, to ‘death and religion’, then to ‘Picasso and girls’.

The Kardomah Gang also plotted and planned their own pursuits; the portraits they would paint, the symphonies waiting to be composed, and as Dylan poetically put it, how they would ‘ring the bells of London and paint it like a tart’. Oo-er. Indeed, they all went on to do just this, Dylan even cracked America, the sign of any successful solo artist.

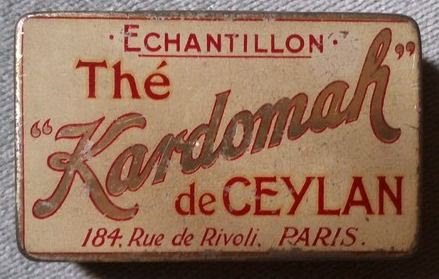

The Swansea café on Castle Street was special, as it birthed the Kardomah Gang, and coincidentally was once the site of the church where Dylan’s parents married in 1903. However, these beatnik chic cafés were dotted all over the UK and even spread to Paris and Sydney at the height of their popularity in the 1950s.

Despite the exotic name, Britain’s first coffee shop chain was born in Liverpool, in 1844. Originally a tea dealing and grocers company, Kardomah evolved into a coffee brand in the 1890s, which still exists today, selling instant coffee.

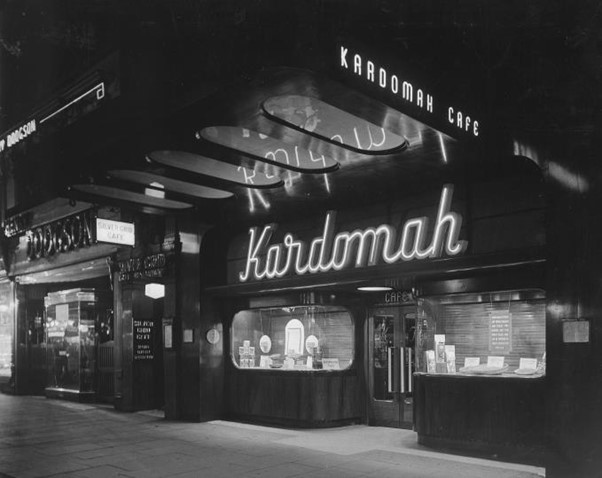

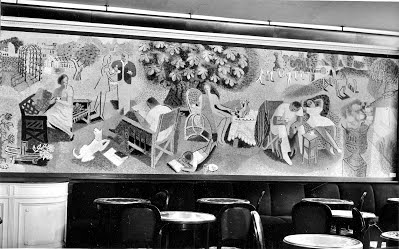

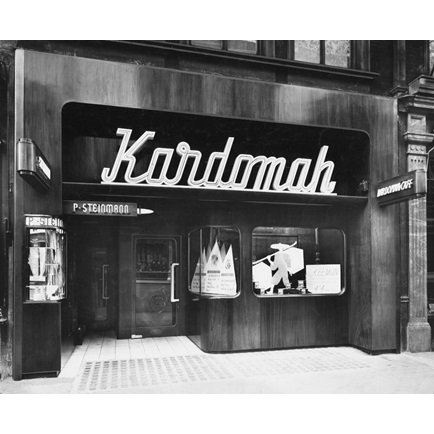

Kardomah coffee was cool, not in a hipster coffee nerd kinda way, but because it opened small towns up to the big buzzing world. The Manchester and London branches were arguably the snazziest as they were designed by Sir Misha Black between 1936 and 1950.

Misha Black was the architect and designer behind the iconic City of Westminster street signs, as well as London Underground’s modernist moquettes. The branch on Manchester’s Market Street had sleek art deco signage and a Hollywood golden age sweeping staircase. This location was a hangout for L.S. Lowry and other Mancunian artists of the day, hatching plans to take the creative world by storm.

There was something in the air in Kardomah cafés around Britain, and I’m not just talking about the smell of coffee, or smoke. Birmingham had a Kardomah Gang of their very own, which rose to prominence from the 1930s to the 1950s, alongside the popularity of the city’s two Kardomahs.

Unlike the all-male clique that was the Welsh Kardomah Boys, the Birmingham Surrealist movement had a female member in their intellectual ensemble, the artist Emmy Bridgwater. She was joined by fellow bohemian painters and thinkers Conroy Maddox, Desmond Morris and brothers John and Robert Melville. They lived by the Surrealist tradition of dreaming while ‘being in the world’ and so would meet informally at the Kardomah café in New Street to discuss their theories. The Brummie Beats were not very well-known at the time and remain that way today. However, in academic circles they are considered the ‘harbingers of Surrealism’ in Britain, after building links with the movement’s French origins through pals André Breton and Salvador Dali. See, you never know what that table next to you in the coffee shop may be plotting.

In the 1960s, Kardomah cafés became the haunts of mods and their lambrettas before gradually dying out. After World War II, many of these havens of great expectations turned to dust and devastation.

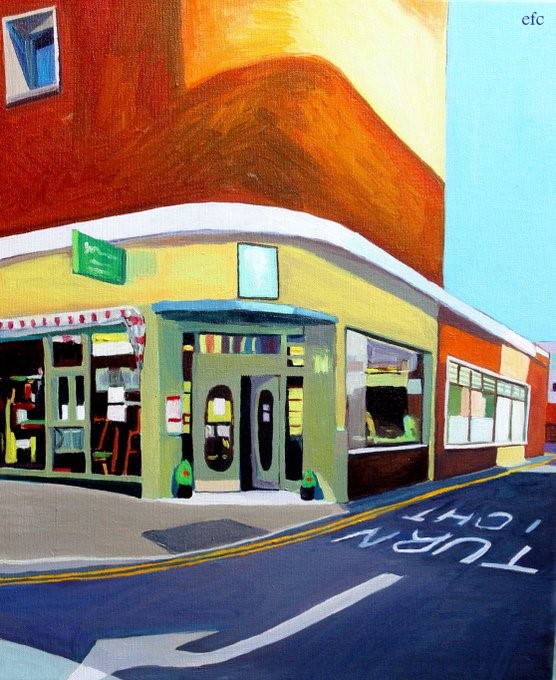

The ‘ugly, lovely town’ of Swansea, as labelled by Dylan Thomas, took a big hit in the Blitz, and the Kardomah on Castle Street was destroyed. Now, do you want the good news or the bad news? Well, it was rebuilt down the road on Portland Street and is still going strong today, but this sadly remains the last standing Kardomah café in the world, a reluctant independent.

Swansea’s relocated Kardomah café opened in 1957 and is still run by the same family today. Many of its current clientele have been loyal customers since it’s rebirth and meet regularly for frothy coffee and good company.

The fixtures and fittings have gone largely unchanged. The genuine 50s retro feel has revived popularity for nostalgia seekers and art deco devotees alike. The joy of this café on the corner is that it hasn’t moved with the times, and what a blessing that is.

You’ll still find the waitresses wearing their lace pinafores, mopping the tiled floor and wiping the wood panelled counter tops at closing time, a scene ripe for a Hopper painting.

‘I first caught sight of my beloved in there, and fell hook, line, and sinker’ says one pictureless profile. ‘We’d always go KD before the cinema on a Friday night‘. ‘The custard slices, oh I can taste them now! ’. This forgotten coffee chain lives on in cobbled together memories on online nostalgia forums. It wasn’t just the ‘Home Sweet Homah’ of the British Beats, but the knickerbocker glory days for the everyday Kardomah boys and girls all over the country.

The last remaining Kardomah café has a lot on its plate, and I’m not just talking about their generous portion sizes. It’s holding a torch for the hidden layers of history which have unfolded in its branches around the country, reminding people that the ripples in your coffee cup can create big waves around the world. Although the Kardomah Gang succumbed to the allure of London and plotted their way out of Swansea, their work shows that you can never, and should never, forget where you came from. Love your ‘ugly, lovely town’ and your friendly local caff, if the British Beats can’t beat it, join them.