Our passports have been gathering some dust since the start of this pandemic, so maybe it’s time we took a moment to find out more about them and consider just how they came to be so important in our lives. Today, the significance on these pocket-sized booklets that allow us to traverse borders, prove our identity, gain access to various privileges, protections and in some cases, even basic human rights, is huge (yet somehow we still manage to lose more than 800 million passports a year). But alas, the passport hasn’t always held so much clout, and there was a time not so long ago, when the idea of a passport was considered a violation of rights, calling for them to be abolished entirely…

The widespread use of passports is relatively new. In 2018, less than half of the American population (up from just 4% in 1990) still weren’t in possession of one. Meanwhile roughly the same number of people in China (120 million) hold passports, representing only nine per cent of the population.

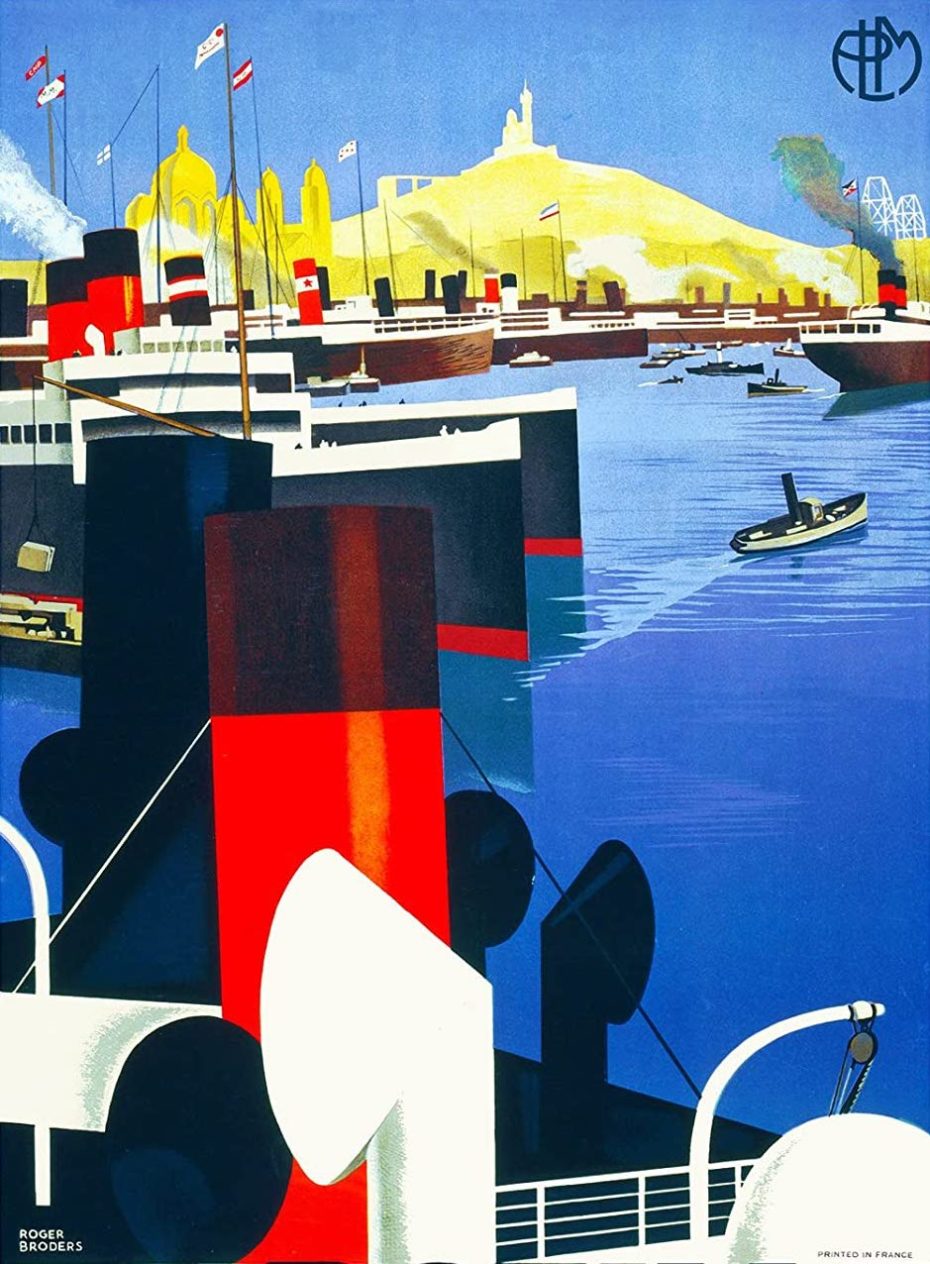

The very word itself, “passport”, came into use during the 16th century and derives from the French words ‘passer‘ (to pass) and ‘port’, which is fairly logical since sea ports were history’s first major hubs of organised travel long before the advent of air and train travel. However, the similar French word ‘porte’ also means door in French, which brings to mind a more romantic travel reference; the idea of a portal to a new world. Let’s say it’s up for interpretation.

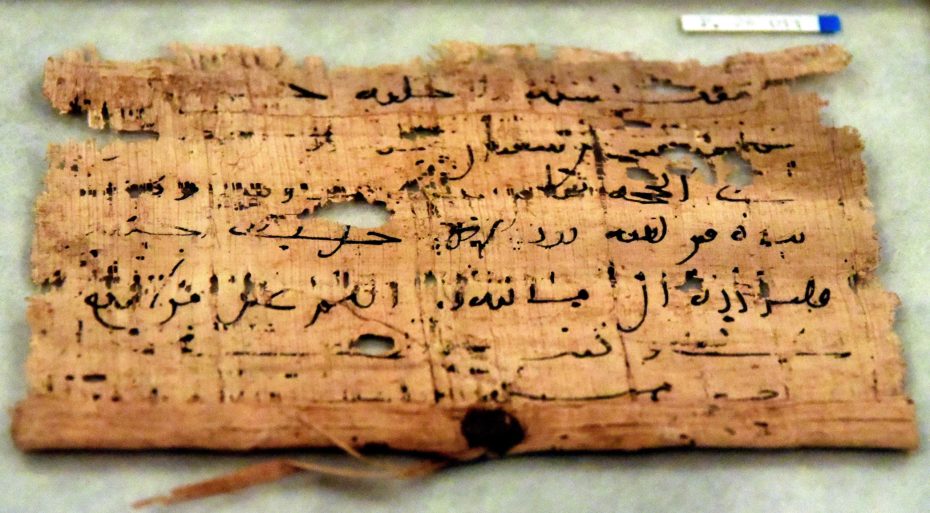

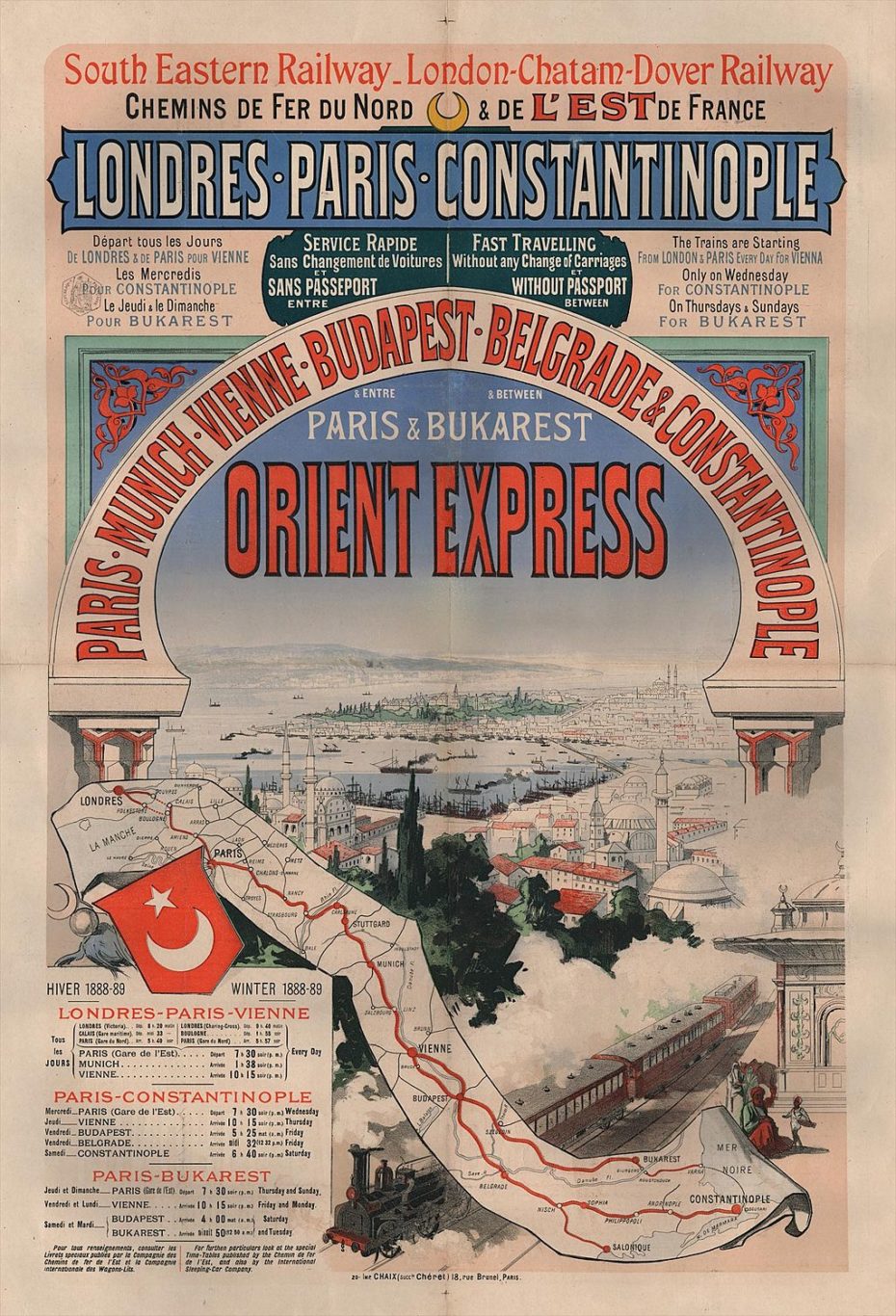

The earliest reference to something that resembles a passport is in the New Testament when Nehemiah was given a letter written by his master, the Persian King, to grant him safe passage across the river. Similar documents were also mentioned in ancient India, the very first dynasty of Imperial China, and medieval Islamic states. But fast-forward to late 19th century Europe, and you could hop on the Orient Express from London without any checks at all….

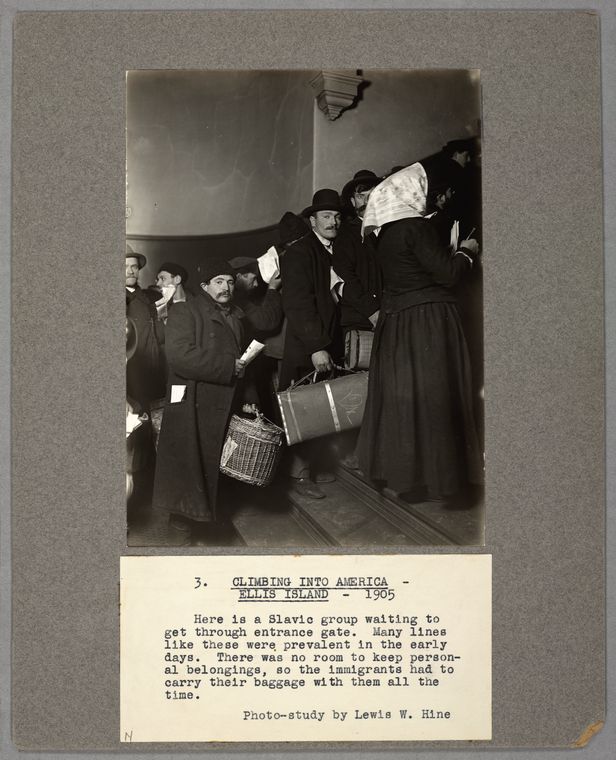

Rail networks were fast expanding and more people were exploring the world and crossing borders via train. It was simply too much paperwork for the authorities to mandate them, so they were ultimately scrapped and even abolished in many countries at the turn of the twentieth century because they were associated with oppressive regimes. In fact, no immigrants to the USA in the 19th century had passports – they simply boarded a ship and arrived in the new world.

Back then, there was no such thing as “illegal” immigration (although there are some exceptions in history, the Chinese Exclusion Act being a significant one). Having safely crossed the Atlantic to Ellis Island, immigrants would be asked a few questions upon arrival (name, age, nationality, family, etc) and sent on their way after clearing quarantine.

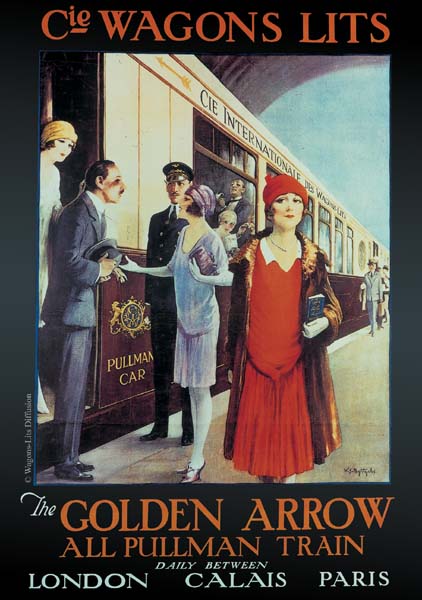

Even at the dawn of the so-called ‘golden age of travel’ of the 20th century, passports were scarcely used and people could travel pretty much anywhere without one. Perhaps the only person on earth who still has that kind of liberty is the Queen of England…

Shakespeare wrote about passports in Henry V, the play that immortalised the warrior King, who of course didn’t need a passport, and to this day, the Queen of England doesn’t require one as they’re all issued in her name. It was under Henry V’s rule in 1414, that the first form of passports are recorded in Britain. As long as one was of a certain standing in society at the time, anyone could be issued a “safe conduct” document by the King himself, citizen or not, while the general lay population would have to pay for such a privilege.

For a vast swath of European history, serfs could not even leave their local area, let alone travel to some other domain. One could however more easily pick up a passport over in France, if they managed to get there. Passports weren’t national documents per se, but rather identity documents.

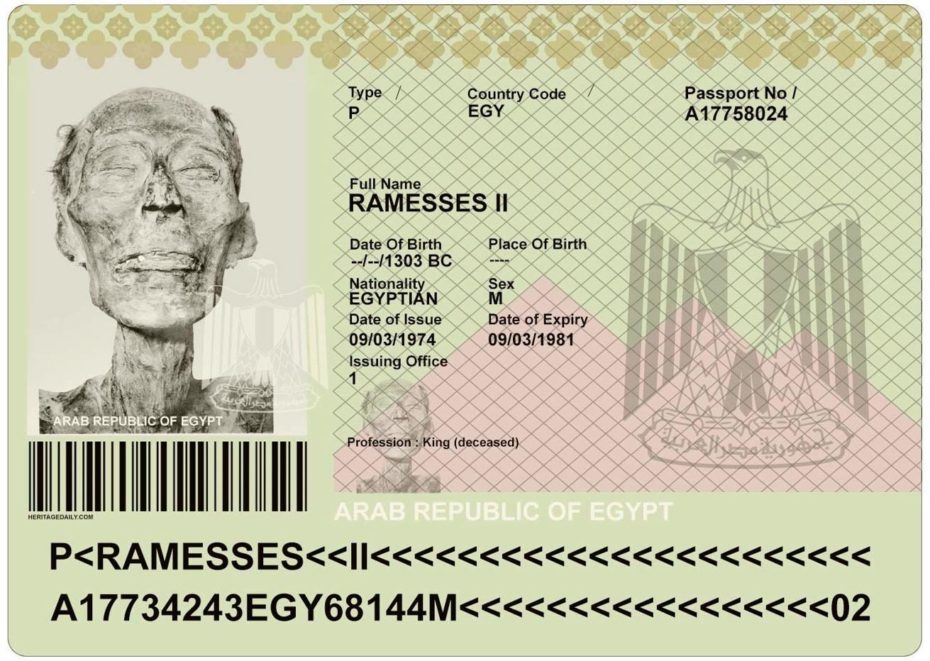

As witnessed throughout history, the rules don’t always apply to everyone. Take Paul McCartney, who in 1967 was travelling to France and forgot his passport. As the story goes, he allegedly pulled the “you know who I am” card and was allowed to board his flight. Meanwhile in 1976, due to a law that anybody (dead or alive) travelling into France officially requires a passport, Rameses II (who died sometime in 1213 BC) required one so that his remains could travel to Paris for study. The Egyptian government did indeed issue the ancient pharaoh a passport.

Passports only became truly widespread after the First World War. In 1914, passports were re-introduced in order to increase domestic security. They were made compulsory in order to know who was moving in and out of countries, to keep an eye out for spies, and to keep skilled nationals at home.

And as Giulia Pines wrote in the National Geographic, “No one, it seemed, much liked the idea of being labeled, packaged, and dehumanized within a passport’s pages, but no one could get around without one.” At this point, passports weren’t being handed out so “laissez-faire” as they were previously. They were becoming much more regulated, strengthening the modern concept of associating identity to one’s nationality. Passports were, according to historian David Cannadine, perceived to be a “threat to civil liberties rather than a safeguard” and were thus once more discarded in the interwar period, until they were revived again at the start of the Second World War, again, for security reasons.

Speaking of security, the 1972 best-selling thriller The Day of the Jackal, the novel intricately details an easy method of obtaining a fraudulent British passport, which was later used by the IRA and the KGB. This loophole went unclosed until 2007, and may have resulted in up to 1,500 fake passports being issued a year.

Fun fact: Actor Ricky Gervais was once the victim of a £200,000 Gold bullion sting where the fraudsters used a fake passport with a picture of David Brent from “The Office” as ID.

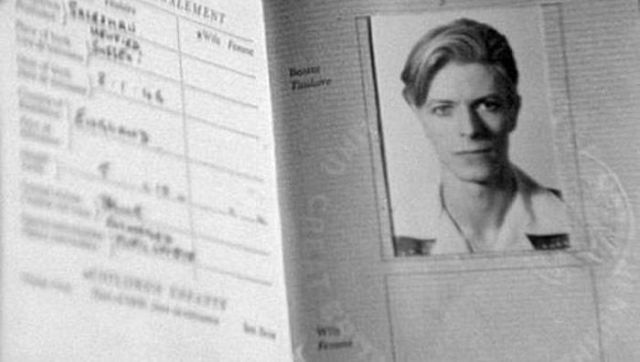

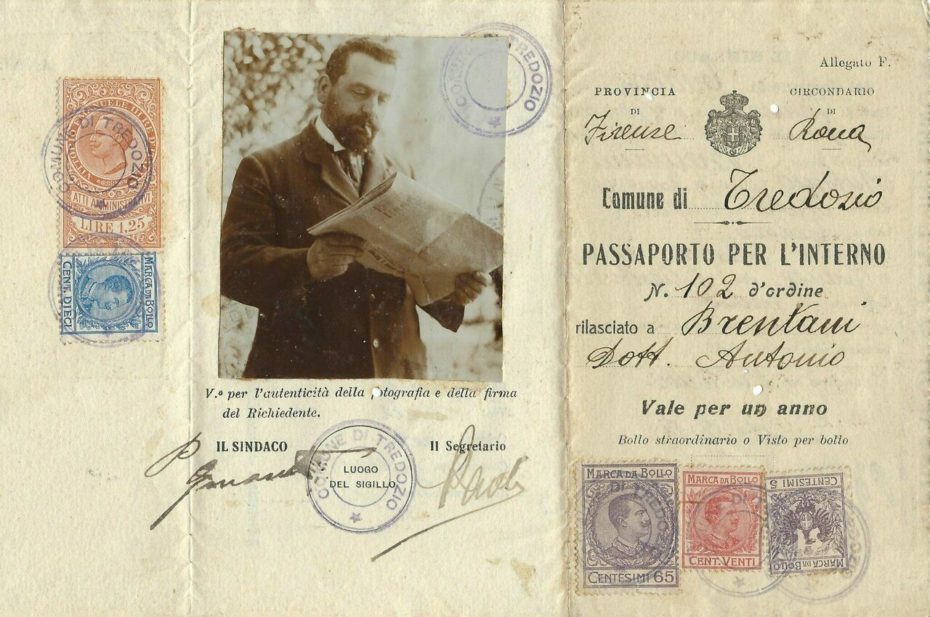

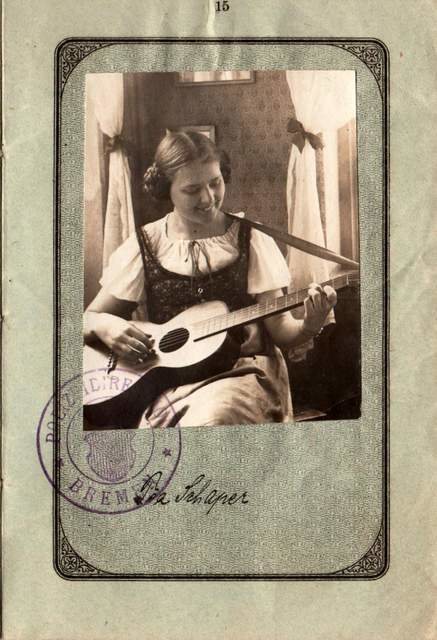

Up until the 1980s, the standards for official passport photos were also slightly more open to some “creative interpretation” and people would sometimes use personal family photographs where they might be casually posing while smoking or holding sentimental possessions, such as guitars, guns and even their dogs.

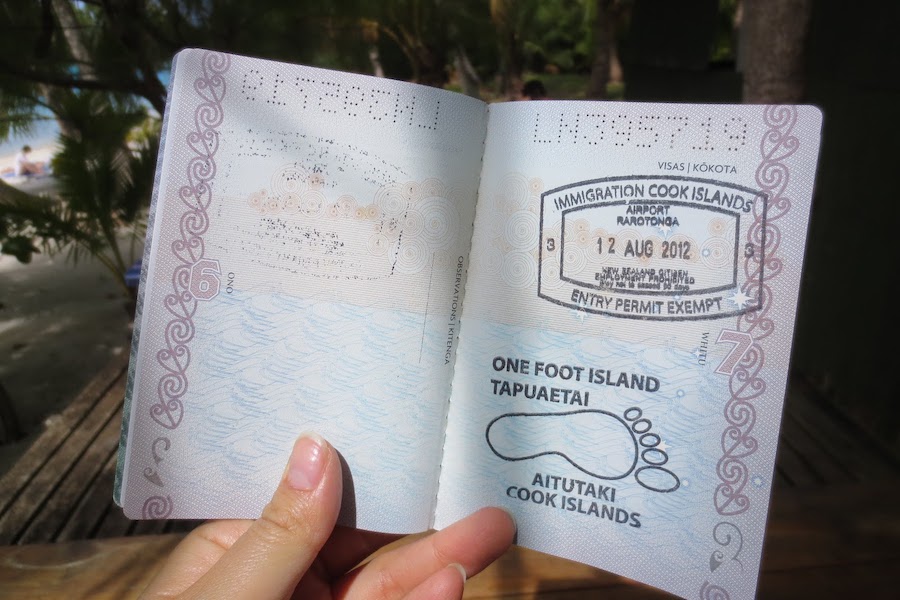

Back then, passports were after all, still treasured booklets full of travel memories; for an old passport full of rare stamps from far-flung or unusual destinations is the world’s best story teller. And if the passport stamp was becoming an endangered species with the introduction of speedy contact-free e-gates before the pandemic, you can bet there’s little hope of a great resurgence now.

Still, there’s room for improvement when it comes to decorating our passports…

While Japan and Singapore are considered as the most “powerful passports” in the world today, granting visa-free access to 189 countries, others arguably compete for the title of “most beautiful”. Combining national pride and some creativity with high tech efforts to prevent forgery, some countries have transformed their passports into works of art using special fonts, inks and secret images, elaborate guilloche patterns, holograms and watermarking. Even the sewed string that binds your passport together is meticulously designed in a special way that makes it obvious if tampering has taken place, and may be micro-braided with multiple colours and fluoresce under UV light.

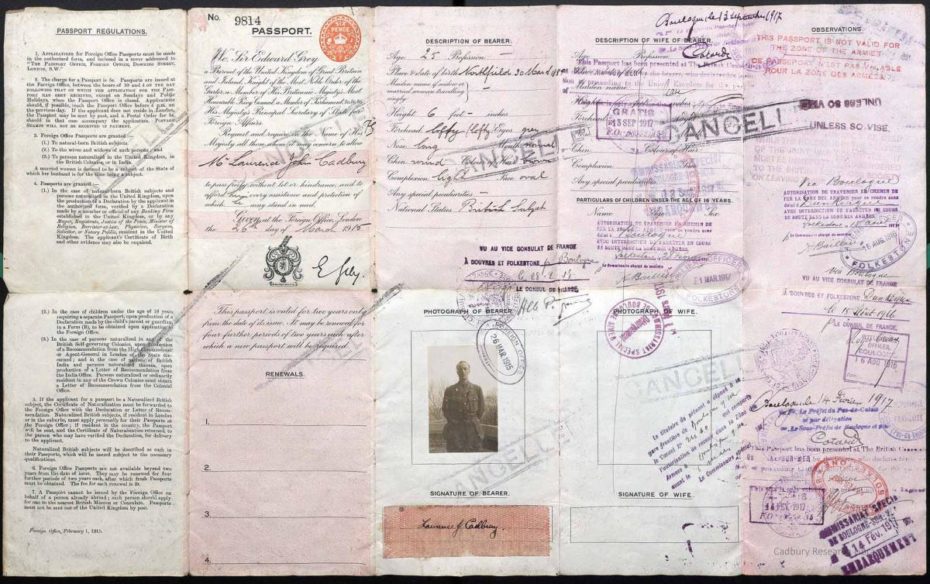

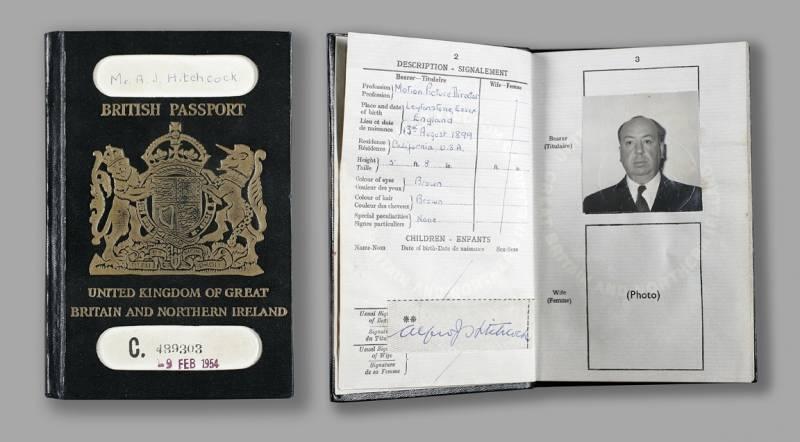

Canada’s 2013 passport redesign became internet-famous for its creative use of blacklight-only images (above). In comparison, the first modern British passport issued in 1915 consisted of just one page including a photograph and signature, which was folded into eight squares and slipped into a cardboard pouch. It was valid for two years.

If you were wealthy, you might have had it in a fancy leather case, and had the paper reinforced with linen. Along with the photo, signature, the document included a list of physical attributes much like today, only slightly more descriptive, for example: “Forehead: broad. Nose: large. Eyes: small”, raising all kind of questions about how this might have fuelled racial stereotyping.

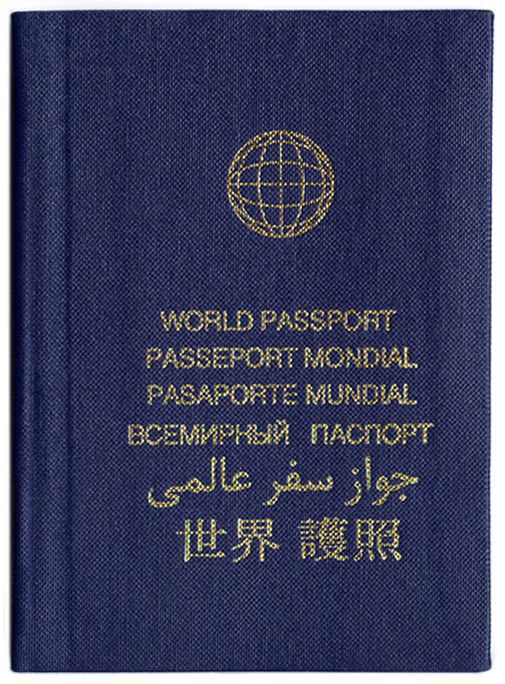

An international peace activist best known for renouncing his American citizenship founded the World Service Authority in 1954, which made it possible to obtain a “World Passport” for use not just as a document for international travel, but a “neutral, apolitical document of identity”. Accepted as travel documents by a very small number of countries across the world, the World Passport falls under the category of a “camouflage passport” or a fantasy travel document and is largely rejected by official governing bodies as a scam. Some notable people have owned World Passports include Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, President Eisenhower (who was gifted one), actor Patrick Stewart (why not), and unsurprisingly, a few criminals and terrorists.

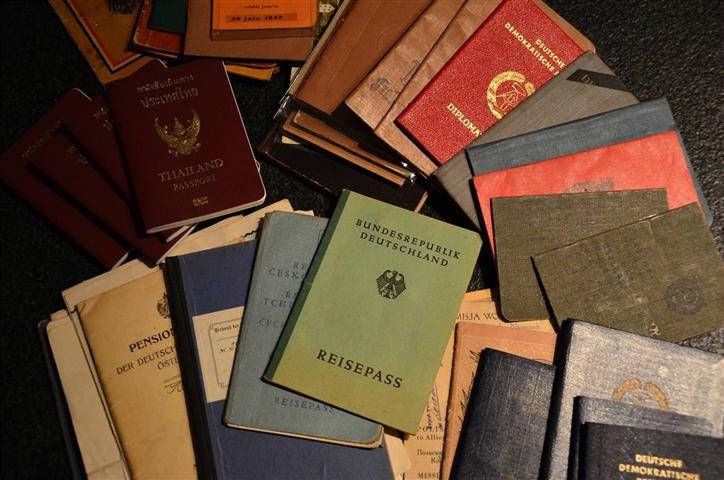

While there is still debate surrounding official travel documents and sentiments of suppression, inequality and surveillance attached to them, especially with new features like microchips, they have become objects of great interest. There is a whole community of collectors. A passport signed by Charles I in 1641 is the oldest surviving British passport, which was incidentally discovered in 2009 when a couple brought it to get valued on a British daytime television show called Flog It!

Celebrity passports often sell for eye-watering prices at auction too. Not so long ago Carrie Fisher’s passport even ended up on eBay. If the idea of starting your own passport collection intrigues you, your first port of call is passport history expert, Tom Topol, who has been collecting expired passports for many years and has amassed more than 700 rare examples. You can follow his pursuits and findings on Passport Collector, such as documents from obsolete regimes including the earliest passports issued to citizens of the GDR, as well as those belonging to kings, queens and travellers of yore.

But while we’re on the subject, why not fish out your passport (make sure it’s still there) give its pages a little flick through for old time’s sake and make a quiet plea to the travel gods that you get the chance to use it again before the end of 2021. And if we don’t meet again before then, here’s to a Bon Voyage!