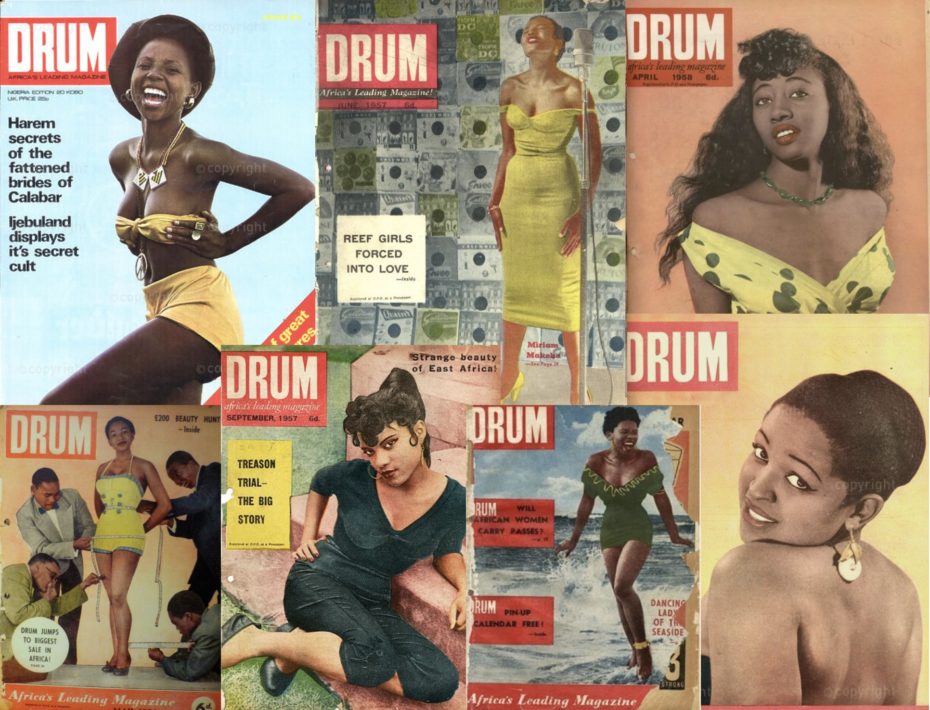

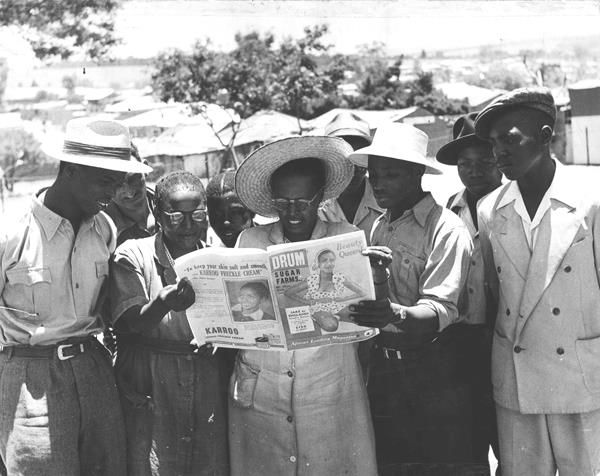

Once described as the “Hollywood of Black South Africa”, in 1951, Sophiatown, Johannesburg was one of the last surviving multiracial neighbourhoods of Apartheid and a symbol of resistance against a racist regime. It was here where the writers of DRUM magazine found their beat and South Africa’s Black celebrities and entertainment found their spotlight. It’s been hailed as “the first Black lifestyle magazine in Africa”, but its heyday was in the 1950s, noted during this era for its early reportage of township life under apartheid. Risking imprisonment, violence, and ultimately, their lives in pursuit of the truth, Drum’s journalists and covergirls blazed a trail for Black South Africans at a time when their freedom was denied, showing the world the true face of Apartheid and capturing the spirit of the Defiance Campaign.

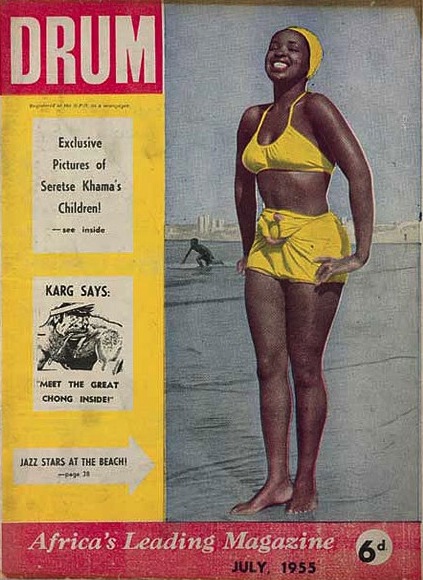

Pictured on the cover of a 1955 summer issue is Dolly Rathebe, who was an up-and-coming actress and jazz singer. Her first cover for the magazine was shot at an old mine dump, by one of Drum’s young photographers, Jürgen Schadeberg. They were both arrested on site for the photo shoot.

He was White, she was Black, and police accused them of being in an interracial relationship, which was illegal under the Immorality Act. For Dolly Rathebe, as a working Black entertainer, such treatment was just a part of daily life, but her impact as a cover girl led the way for others.

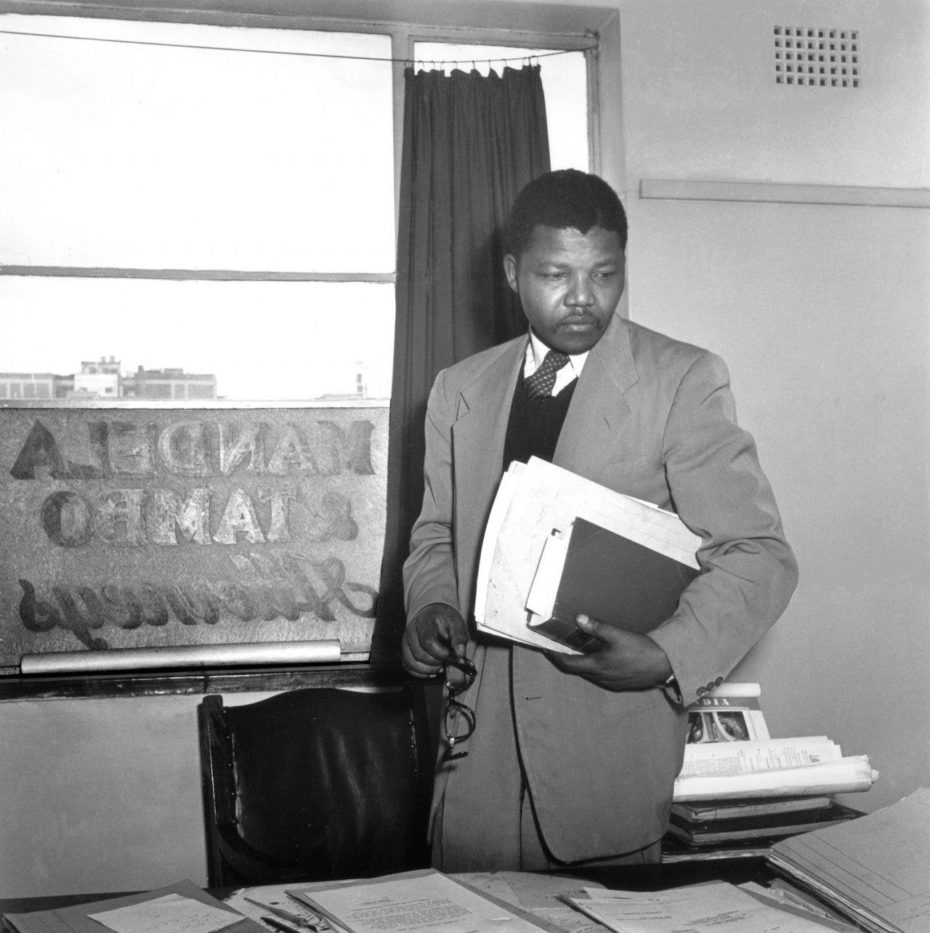

Founded in Capetown in 1951 as “African Drum” by former-cricketer Bob Crisp, the early days of DRUM magazine were problematic on account of their patronising, ‘tribal’ representations of Black South Africans through the White gaze. Failing to capture audiences both domestically and abroad, “African Drum” was a flop facing bankruptcy by its first birthday. That is, until Jim Bailey, a sharp investor and former Royal Air Force pilot, stepped in, replacing Crisp with Anthony Sampson as editor in chief, who would go on to become the authorised biographer of Nelson Mandela. Together, their first line of business included renaming the magazine and moving their offices to Johannesburg, the beating heart of Black culture at the time.

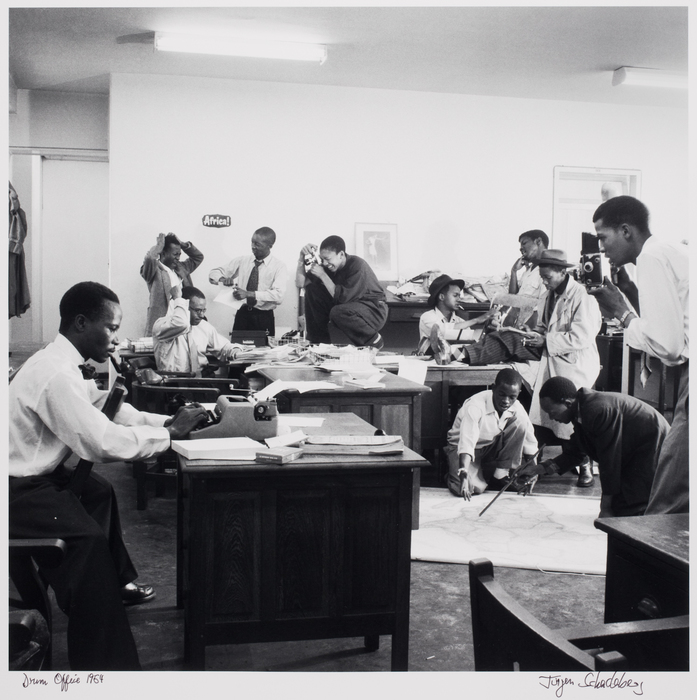

Establishing a task force of talented Black writers, DRUM soon became the continent’s first magazine dedicated to documenting the Black experience in a changing South Africa, where the ramifications of the recently elected National Party’s racist policies were beginning to take full effect.

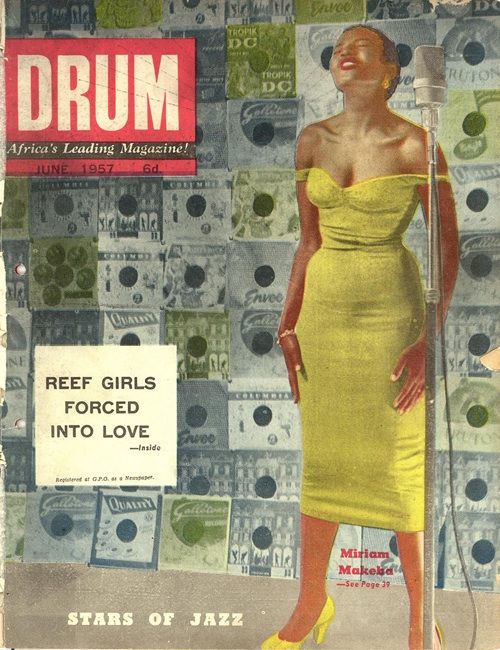

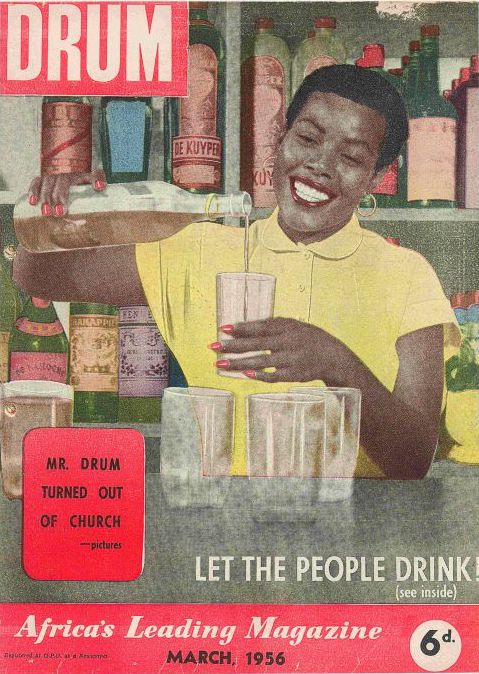

The new and improved DRUM shed a spotlight on the burgeoning arts and culture scene of Sophiatown, South Africa’s answer to Harlem or Saint-Germain. Witty and informed articles covered the township jazz scene which came alive in shebeens (illegal speakeasies), where the music bellowed, drinks flowed, and cover-girls like Dolly Rathebe, Miriam Makeba and Dorothy Masuka sang on stage. People from all walks of life, from poets to gangsters, schoolteachers to artists gathered here, inspiring over 90 of Drum’s short stories about the Sophiatown renaissance.

With Sophiatown as its muse, DRUM told the story of a South Africa where, despite the relentless attacks on freedom and self-expression, Black art prevailed and Black communities resisted. For some readers, the magazine offered a distraction from the oppressive reality of life under segregation, a celebration of Black culture and Black beauty that rejected the White supremacist ideals dominating mainstream South African media. Drum’s journalists moved through Johannesburg’s streets in search of the ideal of African glamour. Cover-girl Dolly Rathebe became the agony aunt, signing off on her “Dear Dolly” letters, helping young lovers find their way. Investigative crime stories with imaginative photography were also popular with readers.

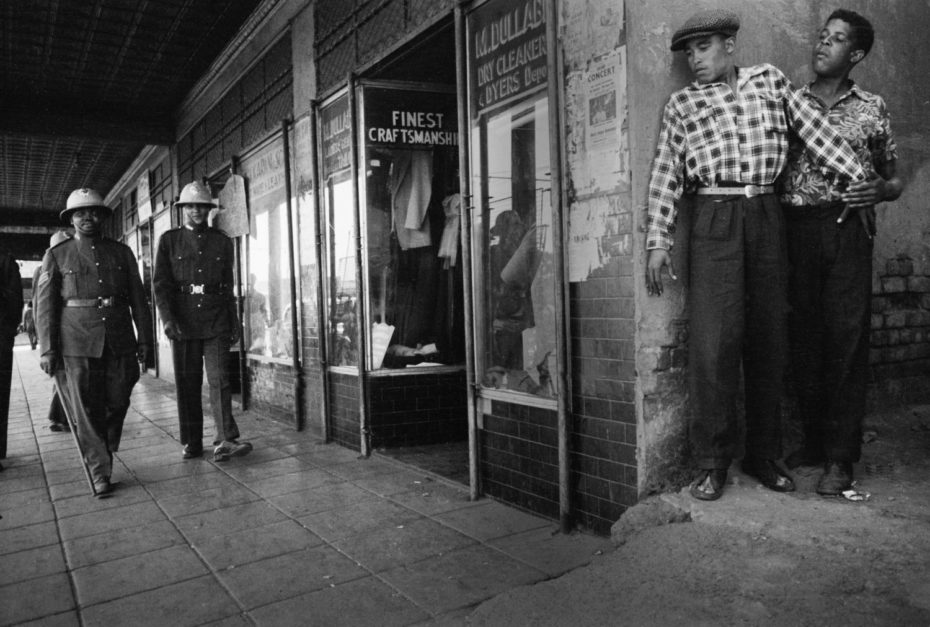

On the other hand, DRUM was also the first magazine to truly expose the multitude of injustices faced by Black South Africans on a daily basis, from police brutality to abusive labour practices and the forced removals of Black communities (including Sophiatown eventually, in 1955) under the Group Areas Act.

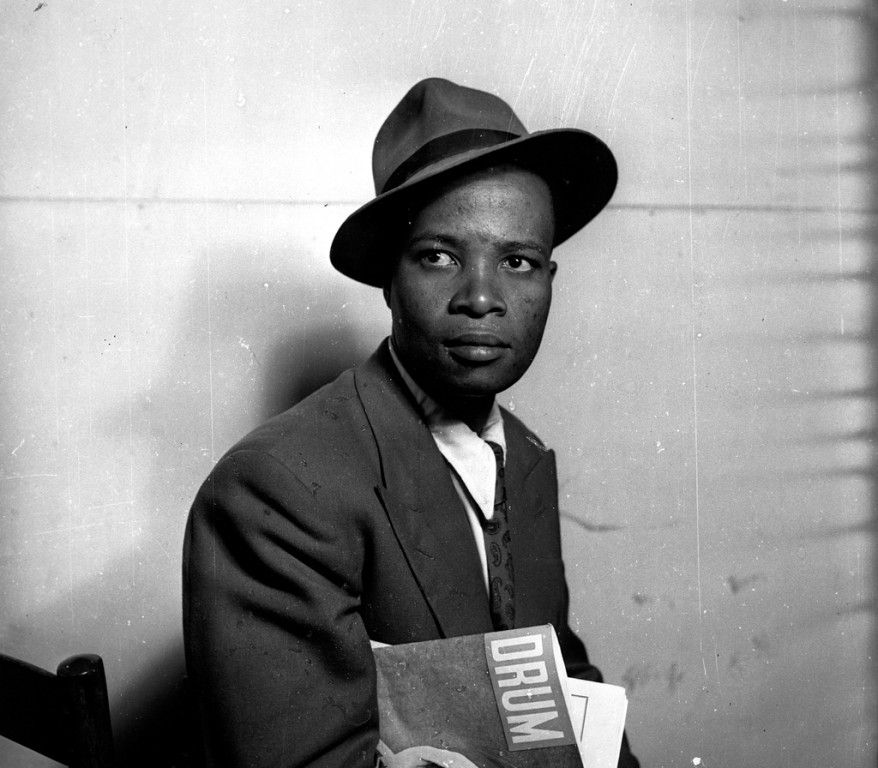

Since Pass laws strictly limited freedom of movement for Black South Africans, DRUM’s editorial team often had to go to extreme lengths in their pursuit of the truth. In one of their first major reports, investigative journalist Henry Nxumalo, affectionately remembered as “Mr Drum”, went undercover as a labourer to expose the horrific slave-like working conditions on a potato farm in the rural village of Bethal. Farmworkers who were tricked into unlawful working conditions and unable to leave freely on account of the contract system recounted stories of beatings, starvation, and even murder. Risking torture and death if captured, Nxumalo managed to escape in the dead of the night and return to Johannesburg to publish the article.

For a piece on the South African prison system, Nxumalo’s intention was to be arrested. Succeeding on his third attempt when he was found without a night pass after curfew, Nxumalo spent five days at the Johannesburg Central Prison, and recounted stories of violence and abuse from the guards. Rumour has it that DRUM photographers Bob Gosani and Arthur Maimane disguised themselves as servants to the warden’s secretary to obtain photographs to accompany his account.

“Mr Drum’s” fearless exposés helped cement DRUM magazine as a force of investigative journalism across Africa while sparking international outrage over the Apartheid regime. Tragically, his life and career were cut short when he was found stabbed to death in 1956. To this day, mystery shrouds the circumstances of Nxumalo’s murder.

Although DRUM was never intended as a political magazine, the editorial team realized early on that one could not tell the story of Black urban life in South Africa without showing the reality of daily life under Apartheid. Though the magazine has been criticised for its problematic heritage and selective coverage of political events – notably, their hesitance to publish reports or images from the tragic Sharpeville massacre of 1960 and their silence on the working conditions for migrant mine workers (attributed to financier Jim Bailey’s family ties to the mining industry) – their coverage of 1950s segregation in South Africa was an indispensable catalyst in the worldwide condemnation of the Apartheid government.

Still, when it came to equal rights between the genders, much like mid-century magazines across the globe, the pages of DRUM left a lot to be desired.

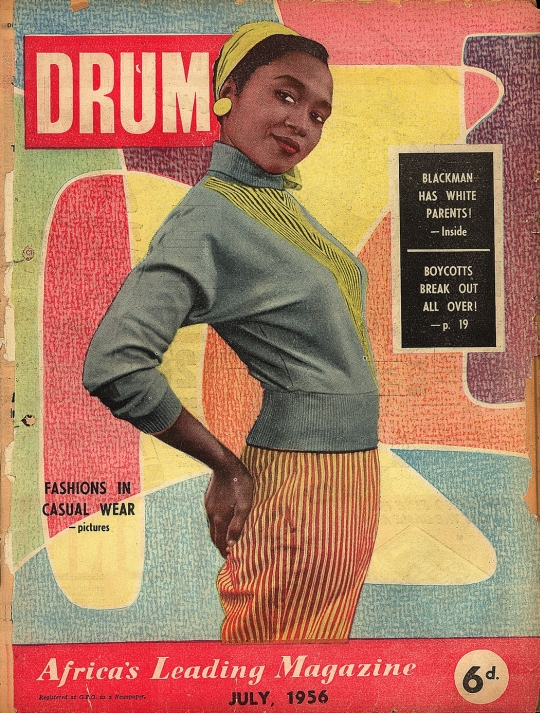

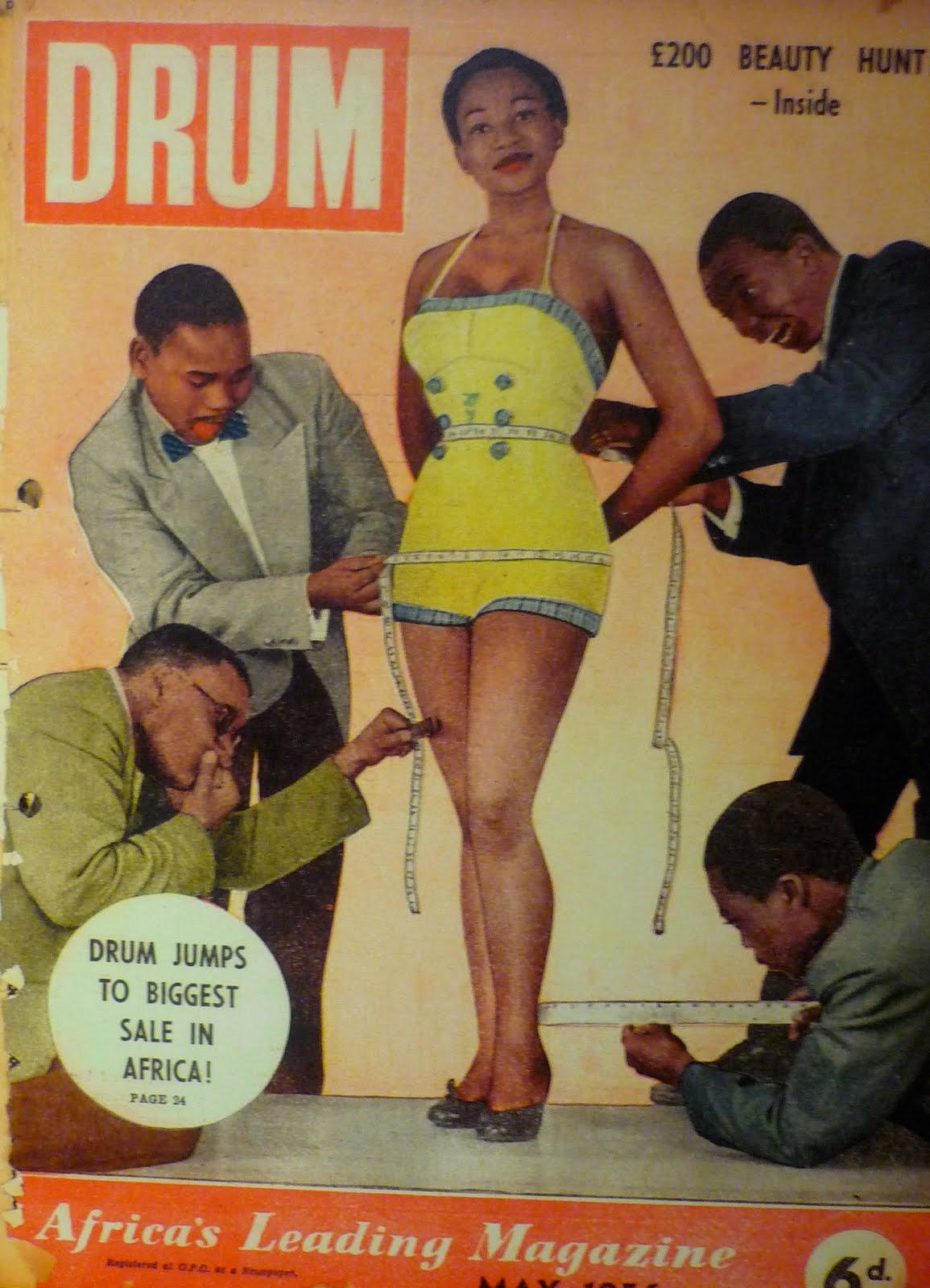

While DRUM did appear to celebrate femininity and copywriters even encouraged men to be at home for mealtimes and help with domestic chores, a woman’s place in the magazine remained under the male gaze, and under his control. Reproducing European and American constructions of gender, DRUM ran its first beauty contest in 1952, which unexpectedly attracted a whole slew of male readers who clamoured to enter the competition themselves. History in fact, dictates that before gender norms took hold, beauty contests were held for both men and women in society as far back as Ancient Greece, and still are in some parts of Africa. For the following year’s contest, the magazine decided to clarify and specify that it was intended for “women only“. And so, gender was being already being defined and reshaped.

Far more troubling, DRUM‘s archives reveal that the magazine regularly ran advertisements for skin-lightening creams, hair straightening treatments and blood-purifying tablets. Such products are also noticeably present in the archives of American magazines like Ebony, Jet and other mid-century Black-owned publications. These cosmetics are still coveted in certain African and Caribbean countries where the image of the sophisticated Black man or Black woman is often held as being in opposition to dark skin.

During a time when seeing a Black model in the 1960s was a rare occurrence in Europe and America, the use of a Black cover girl was indeed groundbreaking under an Apartheid government, but her body was also passively positioned as an object of male desire advertised by the magazine. One of the most popular pin-up girls, Priscilla Mtimkulu, was said to have received 30 proposals of marriage within a fortnight.

If we’re to look for the presence of female staff writers during the magazine’s heyday, unfortunately, we won’t find it. The editor’s decision to have Dolly Rathebe’s popular agony aunt column ghost-written by a male copywriter shows that despite Drum’s aim to promote an equal society, women’s voices were still silenced and a set of ‘feminine voices’ constructed in their place. During the 1960s, only two Black South African women published books in English – from outside of the country.

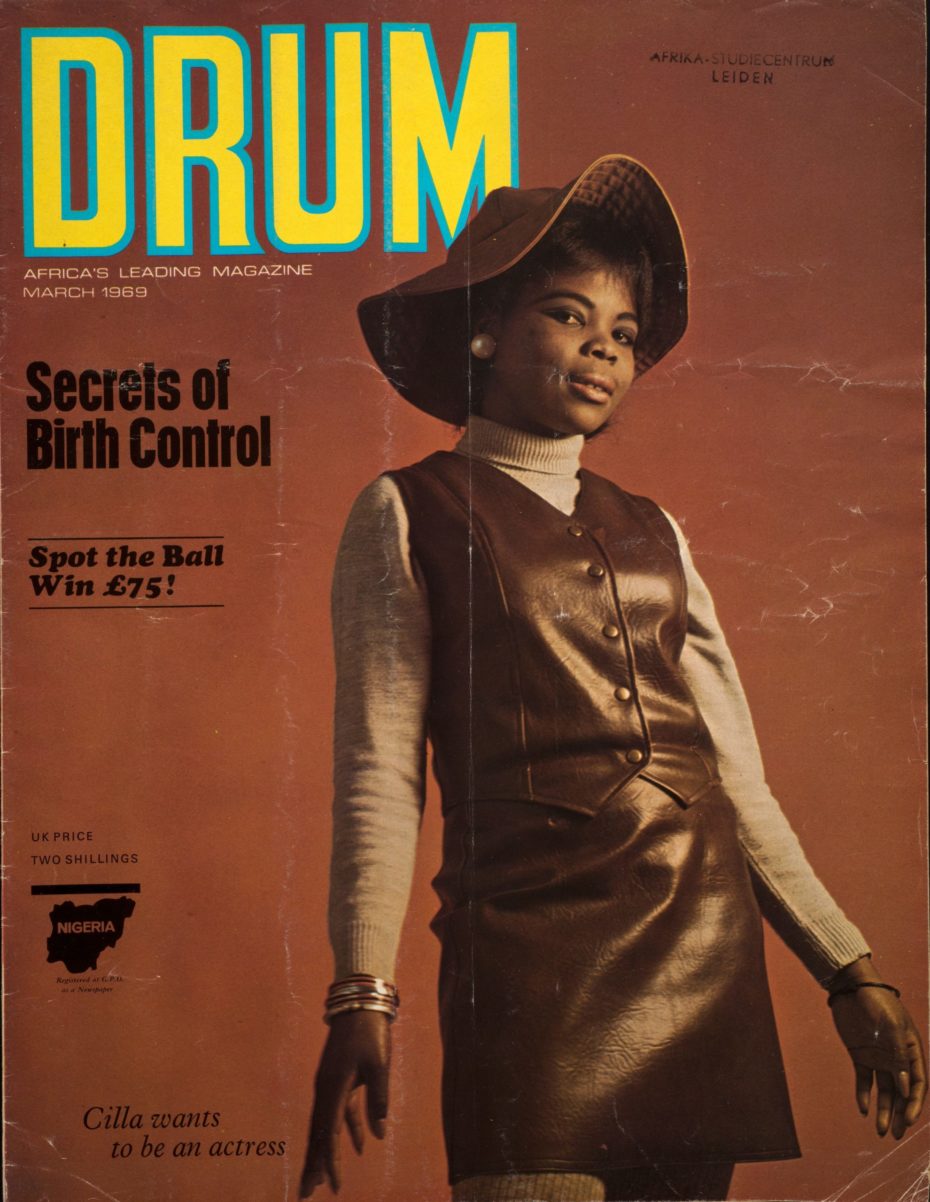

The sixties however did bring about some further improvements at DRUM, as evidenced by the 1965 cover featuring politician, anti-apartheid activist and Nelson Mandela’s second wife, Winnie Mandela. But by 1965, when the Sophiatown renaissance was long over, DRUM had already faded from public favour and become a bi-monthly supplement in the Golden City Post. In its heyday during the 1950s, the magazine sold 240,000 copies across Africa, with special editions printed in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, and Sierra Leone. DRUM was revived in 1968 and today lives on as a bi-weekly lifestyle magazine, the sixth largest in circulation in Africa.

At a time when equal education and employment opportunities were out of the question, DRUM showcased the talents of Black investigative reporters, photojournalists, and creative writers as well as artists and musicians while offering leaders of the defiance campaign a platform to share their message with the world. Even the office telephonist, David Sibeko, became leader of the Pan-African Congress.

“DRUM was a different home; it did not have apartheid,” wrote photographer Peter Magubane. “There was no discrimination in the offices of DRUM magazine. It was only when you left DRUM and entered the world outside of the main door that you knew you were in apartheid land. But while you were inside DRUM magazine, everyone there was a family.”