Do we still have to ask where we are with gender equity on Wall Street? Let’s take stock…

Decades before they had the vote, when women were still shut out of stockbroking on venues like the New York Stock Exchange (among many other things), they took it upon themselves to launch their own Stock Exchange. In 1870, 32 year-old Victoria Woodhull from Ohio became the first female stockbroker along with her younger sister, Tennessee Claflin, when they opened a brokerage firm on Wall Street. Born into an impoverished family, she had already risen from rags to riches by joining the Spiritualist movement to become a sought-after medium; her apparent skills most notably admired by Cornelius Vanderbilt. But Victoria made an even greater fortune on the New York Stock Exchange by advising the business magnate financially, and on one occasion, he followed her advice to sell his shares short for 150 cents per stock, earning him millions on the deal.

To the shock of Wall Street brokers, the young sisters had made their way into the artery of America’s growing place on the international financial stage, a feat which the New York Sun described at the time as “Petticoats Among the Bovine and Ursine Animals.” Headlines varied in positivity, from “the Queens of Finance” to the “Bewitching Brokers,” according to the New York Herald, while other men’s journals published sexualized images of them, insinuating the link between un-chaperoned women and “sexual immorality”, even prostitution. The act itself of buying and selling stocks for a client was seen as a form of gambling in the 19th century; an immoral and unsavoury way to make money for men, let alone for someone so “unstable” as a woman, whose primary duty was to uphold a family’s purity even if her husband couldn’t.

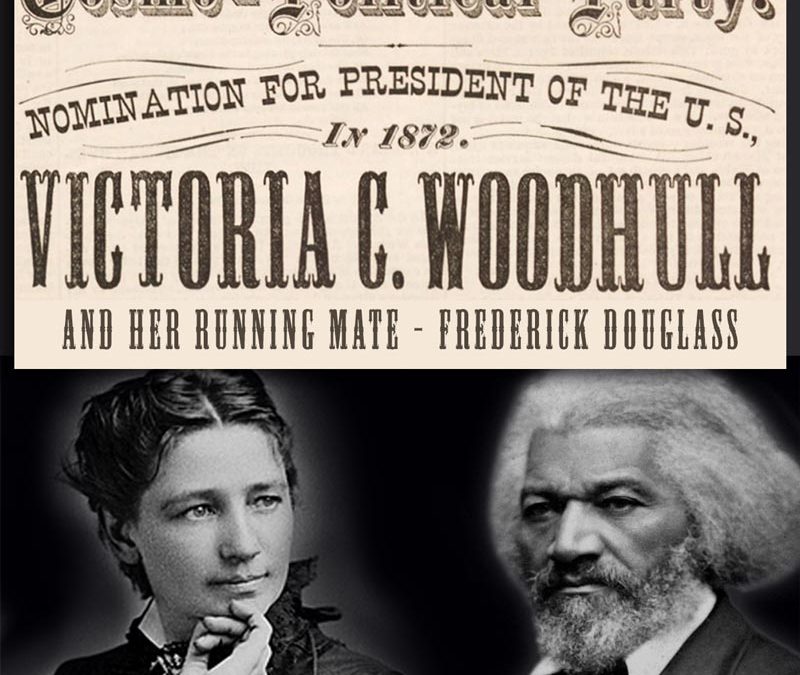

Unfazed, Woodhull and her sister also became among the first women to found a newspaper in the United States, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, as well as prominent leaders of the women’s suffrage movement. And as if that wasn’t enough, before women even had the right to vote, in 1872, Victoria became the first woman to run for President in the United States, with famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass nominated as her running mate by the Equal Rights Party. While the campaign was never taken seriously in mainstream circles (even Douglass didn’t acknowledge the campaign and some historians dismiss her candidacy because she hadn’t yet reached the constitutionally mandated age of 35 to serve), can we just take a moment and imagine what the world might look like today if it had been taken seriously?

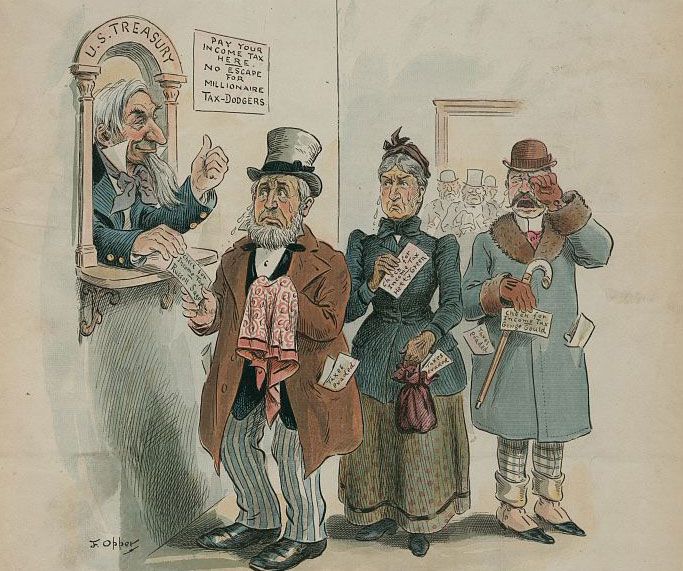

But back to Wall Street circa 1880, where a woman’s presence was being treated with increasing suspicion and another woman-owned brokerage business had popped up on the Lower West Side called the Uptown Stock Exchange. A Mrs. M.E. Favor began to run ads in the newspaper inviting ladies to invest with her. Outrage ensued, as businessmen feared their emotionally-driven wives might be lured to gamble their husband’s fortunes away. Of course, plenty of fortunes were already being gambled away without a woman’s help.

Such was the case for Hetty Green, who became known as “The Witch of Wall Street,” while paying off a number of her husband’s debts and keeping the City of New York itself afloat with loans on several occasions, including the Panic of 1907 when she wrote a check for $1.1 million and took her payment in short-term revenue bonds. Still, Hetty gained a legendary reputation not for being successful, but for being a cheap old wench.

As history remembers it, she only wore black, swore profusely and there were all kinds of rumours circulating about her frugality. It’s said she only ate oatmeal or 15 cent pies, refused to change clothes until they’d been worn out to save on the cost of soap, and allegedly, spent one night searching her entire carriage for a lost stamp worth two cents. “Just because I dress plainly and do not spend a fortune on my gowns,” lamented Hetty, “they say I am cranky or insane.” So this was the general public perception of America’s first female tycoon; of a strong middle-aged and independent woman who had vastly increased her inheritance through shrewd investments. No woman in the Gilded Age made as much money as Hetty Green and estimates of her net worth range from the equivalent of $2.35 billion to $4.7 billion in 2021, making her arguably the richest woman in the world at the time.

“It is the duty of every woman, I believe, to learn to take care of her own business affairs,” wrote Hetty. “A girl should be brought up as to be able to make her own living … whether rich or poor, a young woman should know how a bank account works, understand the composition of mortgages and bonds, and know the value of interest and how it accumulates.”

As for her investment tips? “In business generally, don’t close a bargain until you have reflected on it overnight […] Before deciding on an investment, I seek out every kind of information about it […] I buy when things are low and nobody wants them. I keep them until they go up and people are crazy to get them. That is, I believe, the secret of all successful business.”

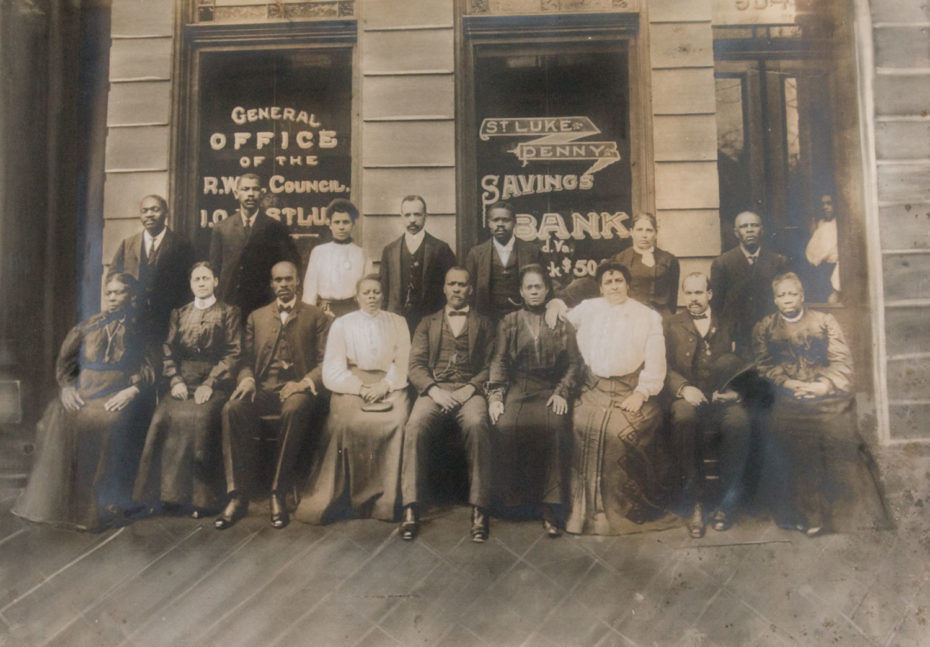

And although her story is not based in New York City or primarily in securities, let’s not forget the Queen of America’s Black Wall Street. Over in Richmond, Virginia, whose Jackson Ward neighbourhood had a booming business and entertainment scene, the first ever bank to be chartered by a Black woman in America, was opened in 1903 by the daughter of a former slave, Maggie Walker. The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank survives to this day as the oldest continuously operated African-American-owned bank in the United States. In 2020, Walker was one of eight women featured in “The Only One in the Room” display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

World War I provided a new moment for women get their foot in the door of finance, at least, temporarily, and under the understanding that it was their patriotic duty. In the absence of men, they were considered to be an important asset for reaching war bond subscription goals. “If they cannot shoulder a musket and fight for their country as men can, at least they can do their part by buying a Liberty Loan.” Women in the work force; notably bookkeepers and stenographers; also played their part in actually selling Liberty Loans.

Before the war in 1910, fewer than a million individuals owned corporate stock in the United States; but after the war, by the 1930s that number had increased more than tenfold. Those who had subscribed to Liberty Bonds were more likely to invest in stocks and bonds, advancing the development of US capital markets. The women who powered the Liberty Bond sales in the absence of male sellers during World War I deserve much of the credit for that. In 1927, the New York Times mentions an Irma Eggleston, who after ten years, had set a national sales record by selling $30 billion worth of bonds.

During the Jazz Age, the first organisations for women in finance originated in 1921 with the beginnings of the Association of Bank Women and the formation of the Women’s Bond Club. Female membership at the New York Stock Exchange wouldn’t become a reality for another four decades, but there is mention of a woman seeking membership as early as 1927.

And there was one brief period in the New York Stock Exchange’s history when women almost entirely replaced men on the trading floor: World War II. Once again, performing their patriotic duty, in the early 1940s, dozens of women filled the empty posts as carrier pages and quote clerks, but they rotated back to off-floor or secretarial jobs when men returned home at the war’s end.

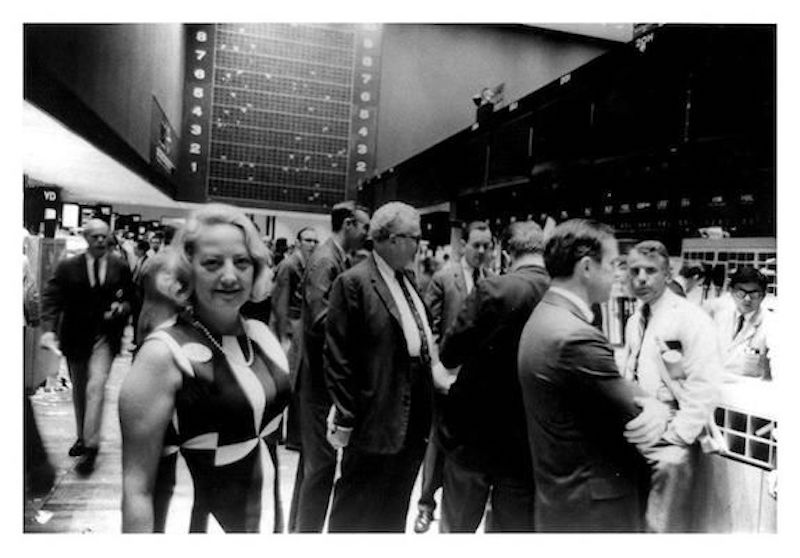

The post-war years opened some new career opportunities for women in Wall Street, notably in 1958 when Mary Roebling became the first woman governor of the American Stock Exchange. In 1965, Julia Montgomery Walsh and Phyllis Peterson became the first women members and most notably in 1967, Muriel Siebert came on to the scene as the first woman to purchase a seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

She was one woman, amidst 1,365 male members. Against the backdrop of the women’s liberation movement, Siebert’s arrival marks one of the most significant pushes for gender diversity on Wall Street, although for many years to come, it would still be a case of grinning and bearing the system. In the 1980s, while there was a small minority of elite women like Elaine Garzarelli, who predicted the 1987 market crash, most faced inhospitable workplaces.

Despite already enduring significant pay gaps, after the 2008 crash, women took the brunt of industry layoffs even though some unpopular opinions questioned whether the crisis would have even occurred had they occupied more positions of power. And then in 2018, a story went viral about 23 year-old Lauren Simmons, who became the only full-time woman trader at the New York Stock Exchange and the second African American woman in the Exchange’s 228 year history to have such a position.

How is it that in this day and age, stories of women working on the stock exchange are so surprising, so rare that they become newsworthy? More than 200 years ago, when 24 men stood under the branches of a buttonwood tree outside 68 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan and signed on as founders of the New York Stock Exchange, women were already participating in the formation of the young nation’s capital structure.

Founding Father First Lady, Abigail Adams secured large gains in trading bonds over farmland and persuaded her husband John to get in on the action early. In 1759, a whopping 61% of investors in the Pennsylvania Indian Commission Loan were women. How have we not come leaps and bounds since then, for a woman’s presence on Wall Street to no longer be a curious novelty, but commonplace?

So everyone’s talking about the latest stock exchange saga, and maybe you’re feeling a little out of your depth chiming in amongst those with a little more experience. Well now you’ve got something just as valuable to bring to the table of conversation.