There’s a reason why Google autofills questions about the authenticity of Black presence in 17th and 18th century Europe – lots of people are asking. The hit Netflix show Bridgerton is Shonda Rimes’ first historical drama, but anyone who enjoys the screenwriter’s work (be it Grey’s Anatomy, Private Practice, Scandal and many more), knows that you can count on her to bring the diversity.

Period dramas set in Europe tend to be entirely devoid of diversity, but not with Shonda. And if you thought Bridgerton was a wholly fictitious picture of the Regency era, think again. What most people don’t know is just how present Black people were in 18th and 19th century Europe – at literally every level of society.

Before writing her book Black London: Life before Emancipation, author Gretchen Gerzina walked into a well-known London bookshop one day, and asked for for the paperback edition of Peter Fryer’s exhaustive Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. “Madam, there were no black people in England before 1945.” This of course, is false. Off by just a few centuries, Africans were already known to have likely been living in Roman Britain; as early as the 3rd century AD, a troop stationed at Hadrian’s Wall was reported to include Black soldiers, and in medieval times, Black musicians were a common feature of Britain’s courts. This commonplace, revisionist misconception is just what Gerzina wanted to tackle (and we highly recommend reading the result).

Now granted, Bridgerton sits in the steamy Harlequin fantasy romance genre, but the point that Shonda Rimes’ light-hearted series surreptitiously raises is that history has been largely written by its “winners”; through White eyes; and that the full story is still in the process of bringing itself to light. So let’s shine our spotlight on the Black historical presence in Europe, from the aristocratic and royal circles, bohemians and artists, early activists and political pioneers to the working class…

The Royal Circle and Aristocracy

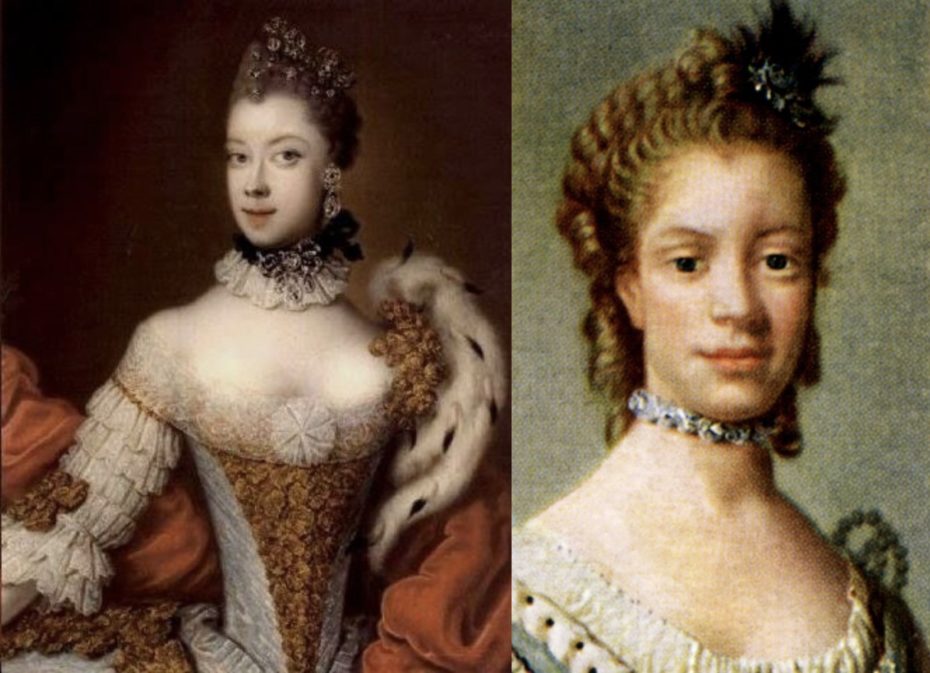

Queen Charlotte, “Britain’s First Black Queen”?

The rumour that Queen Charlotte was of Black ancestry has been circulating since the 1940s, but a historical researcher claimed outright in a 1999 PBS documentary that Charlotte had an “unmistakable African appearance.” The 1761 Allan Ramsay portrait (pictured below) was cited as evidence, supported by her direct lineage from what has been claimed to be a “Black branch of the Portuguese Royal House”.

During the press frenzy amidst the newly announced engagement of Meghan Markle and Prince Harry, numerous comparisons to Britain’s rumoured first Black Queen were made. When asked about the 18th century monarch who was married to the mad “King George”, a Buckingham Palace spokesperson told the Boston Globe: “This has been rumoured for years and years. It is a matter of history, and frankly, we’ve got far more important things to talk about.”

Whether Queen Charlotte was “actually” of Black ancestry may never be known (it’s disputed that she was in fact of Mozarabic ancestry), but attitudes toward her ethnicity alone, reflective of contemporary (mis)information, are worth examining.

As for Queen Charlotte’s portrayal in Bridgerton, played by Golda Rosheuvel, we’d argue that her interests went far beyond matchmaking. Charlotte was a keen botanist, a patron of the arts (a young Mozart was often invited to the palace) and she founded numerous orphanages as well as a hospital for expectant mothers. She was also close friends with Marie Antoinette.

Dido Elizabeth Belle

Until the early 1990s, this portrait was simply titled The Lady Elizabeth Murray, and her conspicuous Black companion portrayed on almost equal terms; at eye level and with a charismatic, direct gaze; was assumed to be her “servant”. It later came to light that the unlikely sitter was Dido Elizabeth Belle, daughter of Sir John Lindsay, a Royal Navy officer and a beautiful slave girl he’d found chained to the hull of an enemy Spanish ship captured in the Caribbean. Dido was brought to England in 1756 and grew up as the adoptive sister of her cousin Lady Elizabeth, an orphan also raised at Kenwood House, a neoclassical villa with the best views of Hampstead Heath. It also happens to be one of London’s most stunning house museums today, with an art collection to rival the Tate and a jaw-dropping library boasting a perfectly pastel ‘Wes Anderson’ colour palette.

John Lindsay’s uncle, Earl William Murray and his family raised and educated Belle as a free gentlewoman and she enjoyed semi-aristocratic status, admired for her refined accomplishments. It’s suggested Dido helped influence the Earl in his abolitionist sympathies while doing secretarial work for him, and in his will, Murray conferred her freedom and made her an heiress. In 2013, Dido’s story was dramatized in the movie Belle, starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw:

The family commissioned a now-famous portrait of Dido and Elizabeth playfully posing on the terrace of Kenwood House (seen above), described as one of Britain’s most unique paintings “depicting a Black woman and a White woman as near equals”. A replica of the piece hangs on the villa’s walls today (the original was moved to Scone Palace in Scotland). There is plenty to learn about Dido’s life at Kenwood House, which is staffed by a lovely team of volunteers stationed in every room offering softly whispered anecdotes about the objects or paintings they might notice you admiring. The incredible art collection includes Rembrandt, Turner and Vermeer to mention a few and the 18th century interiors will leave you agasp.

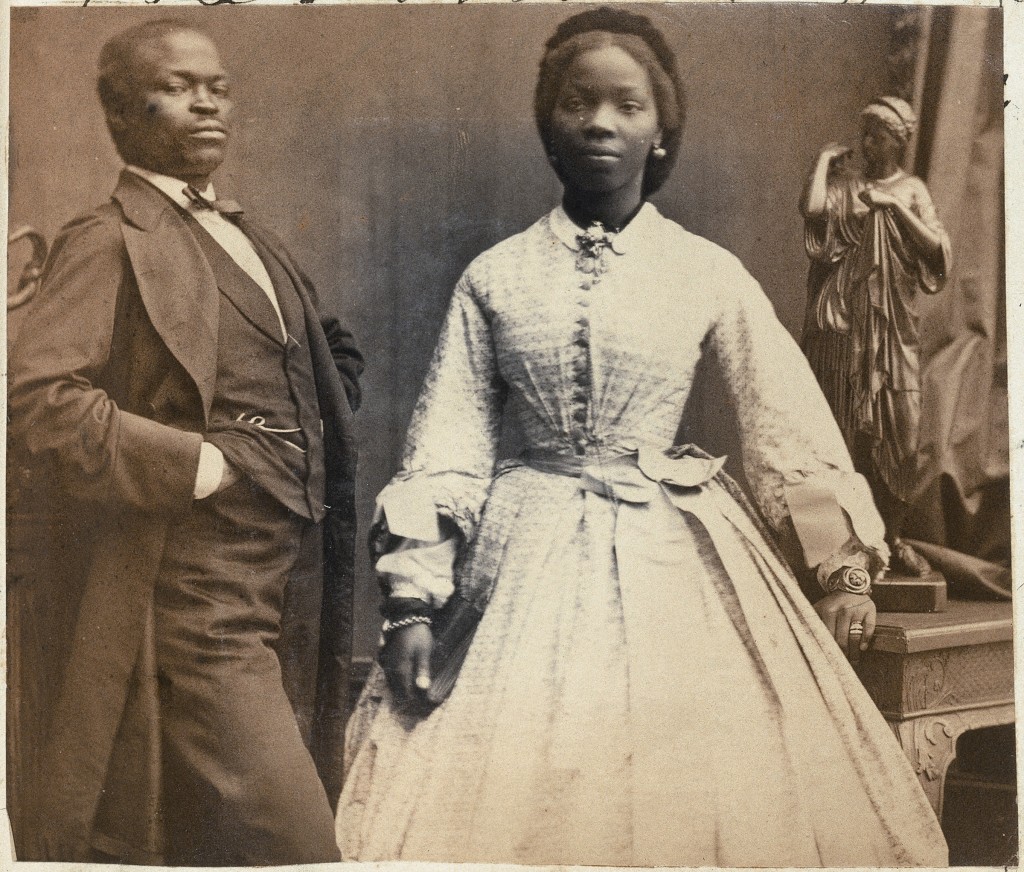

Sarah Forbes Bonetta, Queen Victoria’s God-Daughter

Her parents were tribal royalty, but they were killed in a brutal raid on her village. Sold into slavery at the age of 4, she was later presented as a gift from King Gezo of Dahomey to Queen Victoria at the age of 7. Sarah (now named) won the Queen over with her natural regal manner, and after noticing her talent and passion for learning, not only did Queen Victoria personally pay for Sarah to receive a higher quality education, but the monarch also made the former princess her own goddaughter.

Where history is often concerned with laws and battles and kings, the story of Queen Victoria’s African goddaughter has been left out of the history books. Read her full story here.

In the Arts

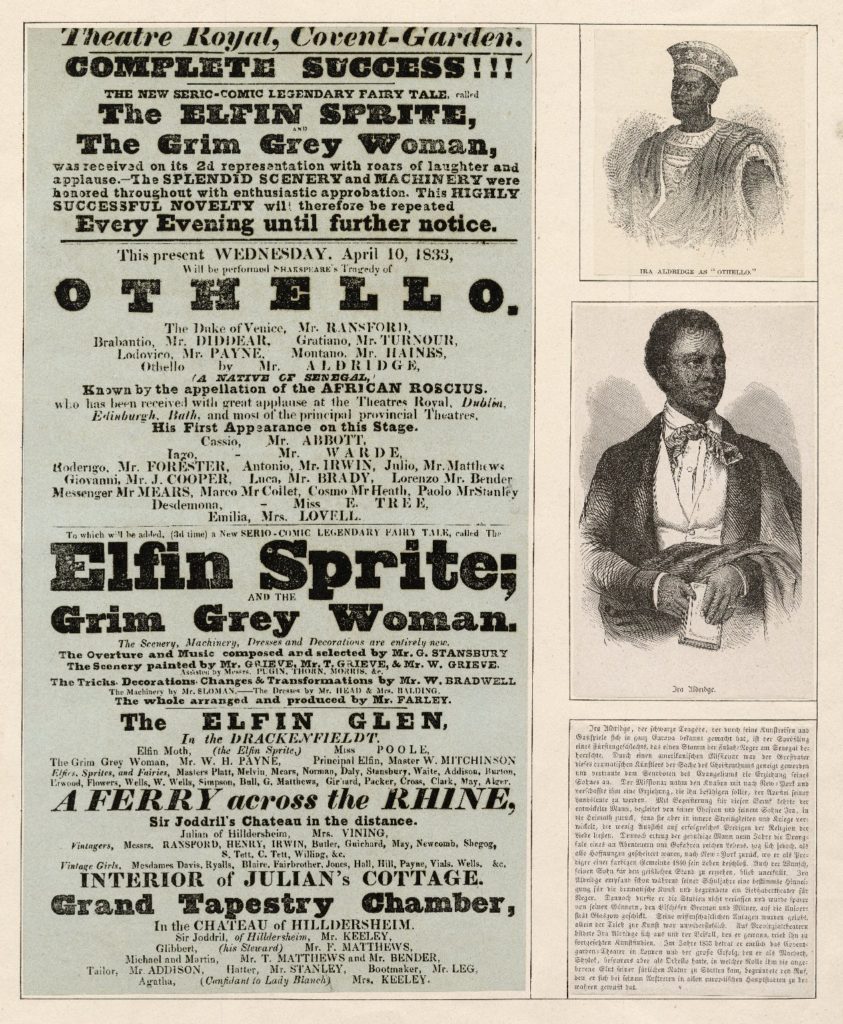

Ira Aldridge, Shakespearean Actor

Preferring to call himself a “scion of Senegalese royalty” rather than an American, Ira had to pursue his career in Europe after his life became endangered for taking on roles like “Romeo” with the African Company in New York. He wasn’t the first Black Shakespearean actor, but arguably one of the greatest.

At 17 years of age, he played “Othello” at the Theatre Royal, Covent-Garden, becoming the first Black actor to play a Shakespearean role in Britain. Othello is a role written by a White man intended to be played by White actor in Black makeup, but the fact that Shakespeare put them into mainstream entertainment reflects the fact that they were a significant element in the population of London. During Elizabeth’s reign, before the English were slave traders or had major colonies, historical research shows the Black people of London were mostly free. According to historian Miranda Kaufmann in her book Black Tudors: The Untold Story, it was a period of relative acceptance and some indeed, both men and women, married native English people.

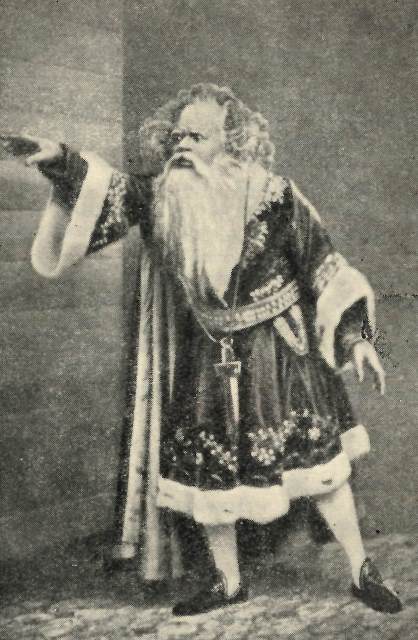

Orson Welles and Lawrence Olivier continued to play Othello well into the 20th century, but Ira Alridge can be considered an pioneer in transforming attitudes towards roles performed “racial impersonation” on the stage. But even London wasn’t without its racist critics. As he toured the country, taking on other starring roles including Richard III, Shylock, Iago, King Lear, and Macbeth, he often made public speeches on the evils of slavery, inspiring abolitionists. “Largely forgotten by theater historians,” he found greater fame touring Europe and Russia before returning to England with wider acceptance. He remains the only actor of African-American descent of the English stage honored with bronze plaques at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon.

Fanny Eaton, Pre-Raphaelite Muse

Meet one of art history’s most prolific but largely forgotten muses, who captured the attention of a secret society of rising young artists called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Fanny Eaton was born in Jamaica in 1835, and in the 1840s, Eaton and her mother immigrated to England. She was employed for about a decade as a domestic worker before she started to model for pre-Raphaelite painters like Simeon Solomon, William Blake and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose work helped redefine Victorian standards of beauty and diversity.

Invited into the bohemian arts world, she regularly sat for life classes at the Royal Academy of London at a time when Black individuals were significantly underrepresented, and typically negatively represented in art. Portrayed as everything from a slave girl to the sister of Moses, she was nevertheless held up as a model of ideal beauty, helping move artistic inclusion forward.

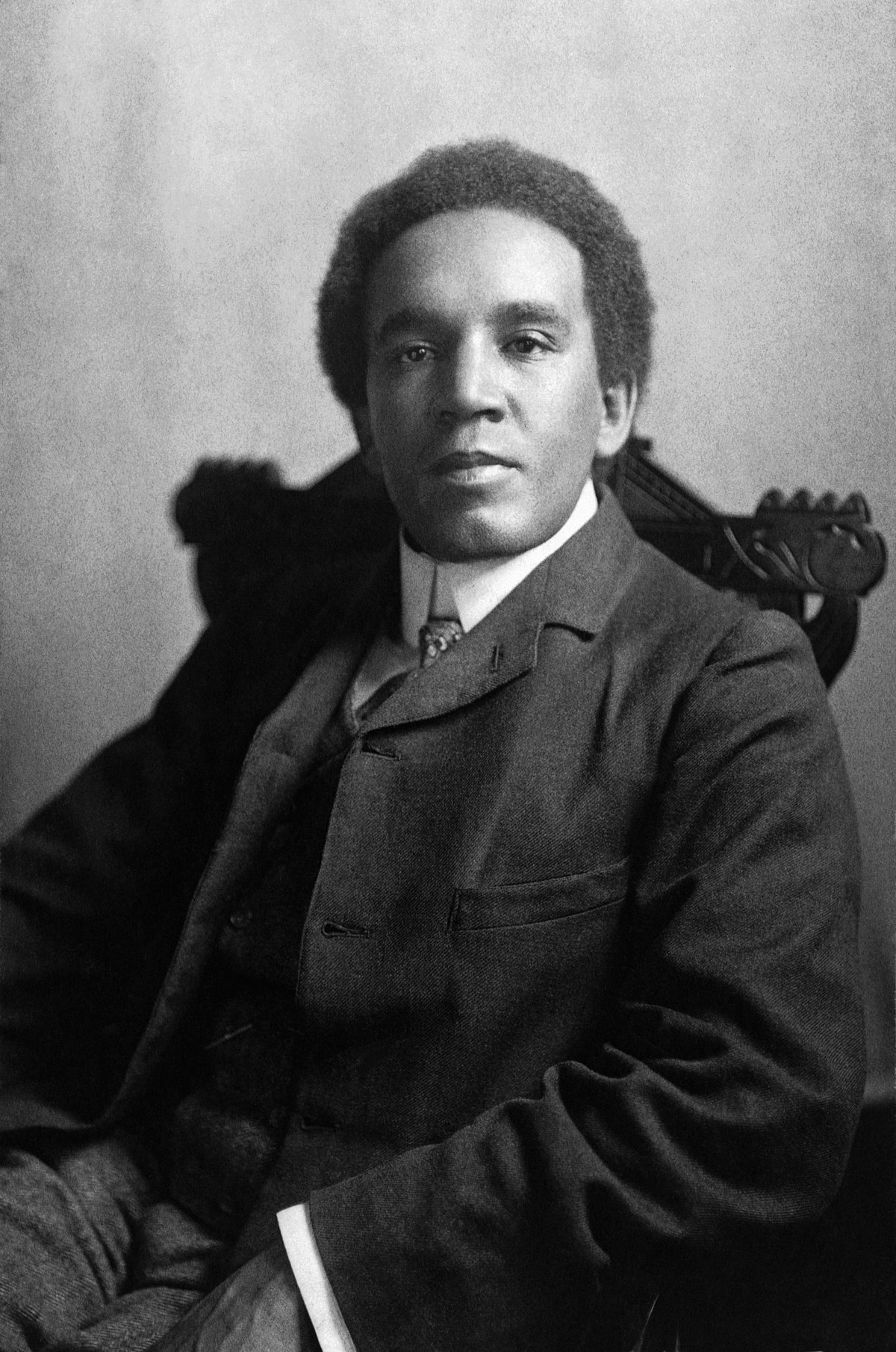

Samuel Coleridge Taylor, Composer

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was a composer and conductor, most famous for three cantatas on the epic poem, Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. One interesting thing to note is that this is the first of bi-racial people on our list who was born to a White mother and a Black father. One might ask the question of why this pairing was the less common, or if this was perhaps one of the few sets of parents in which neither parent was a slave. His father was Dr. Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, a Krio from Sierra Leone who returned to Africa without learning that his mother Alice Martin was pregnant, since they were not married. He studied at the Royal College of Music from the age of 15, was later appointed a professor at the Crystal Palace School of Music and conducted the orchestra at the Croydon Conservatoire. He drew from traditional African music and integrated it into the classical tradition and in 1904, Coleridge-Taylor was received by President Roosevelt at the White House.

This documentary made about him in 2013 includes performances of several of his pieces, and tells the story of his prominent place in music.

Alexandre Dumas, Author

Despite seeing all those90s films that were adapted from his books (and featured nearly all-White casts), The Three Musketeers, The Man in the Iron Mask, and The Count of Monte Cristo to name a few, many of us still remain unaware that their author was Black.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67307740/Portrait_d_Alexandre_Dumas_par_Nadar__1855.0.png)

Dumas’ mother was an enslaved woman in present-day Haiti, and his father was a French nobleman. Like Dido Elizabeth Belle, he was whisked away by his father to France and given an education and military career. His writing earned him great financial success and his country hideaway outside Paris, the Château Monte (named after his first successful novel), was often filled with strangers who took advantage of his generosity. He spent lavishly on women and sumptuous living (researchers found that he had a total of 40 mistresses). Dumas is an unmistakable Titan of the written word, but the circumstances of his birth lead to several similar uncomfortable questions: why did he not write more about his origins in Haiti?

Early Activists and Politicians

Olaudah Equiano, Abolitionist

Writer and abolitionist, Olaudah Equiano was born around 1745 and was kidnapped from his Ibo home in Nigeria when he was a child. He survived the Middle Passage to Barbados on a slave ship by sheer miracle. His biographers note that he was “unusually lucky” in that he was “taught to read in London at the age of 12… and he was eventually able to purchase his own freedom (for £40 in 1766).”

He is best known as Britain’s first Black political leader and the author of the best-selling autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, which became one of the earliest-known examples of published writing by an African writer to be widely read in England. By 1792, it was a best seller. The biography details his survival on the slave ship, fuelling a growing anti-slavery movement in Great Britain, Europe and the New World.

He worked to improve economic, social and educational conditions in Africa and also became involved in helping the Black Poor of London who were mostly African-American slaves freed after the American Revolution. Equiano became a prominent figure in London and developed a friendship with the Countess of Huntingdon who helped promote his book.

John Richard Archer, London’s First Black Mayor

John Richard Archer was born in 1863, but at the start of the 20th century, he was elected Mayor of Battersea, which made him the first Black mayor in London. The election itself was fraught with racism against him, but he won nonetheless. He also staunchly supported the Pan-African movement, made famous by Malcolm X.

He was reelected several times, but at his first victory, part of his acceptance speech said: “My election tonight means a new era. You have made history tonight. For the first time in the history of the English nation, a man of colour has been elected as mayor of an English borough. That will go forth to the coloured nations of the world and they will look to Battersea and say Battersea has done many things in the past, but the greatest thing it has done has been to show that it has no racial prejudice and that it recognises a man for the work he has done.”

Black Working Class in Regency Britain

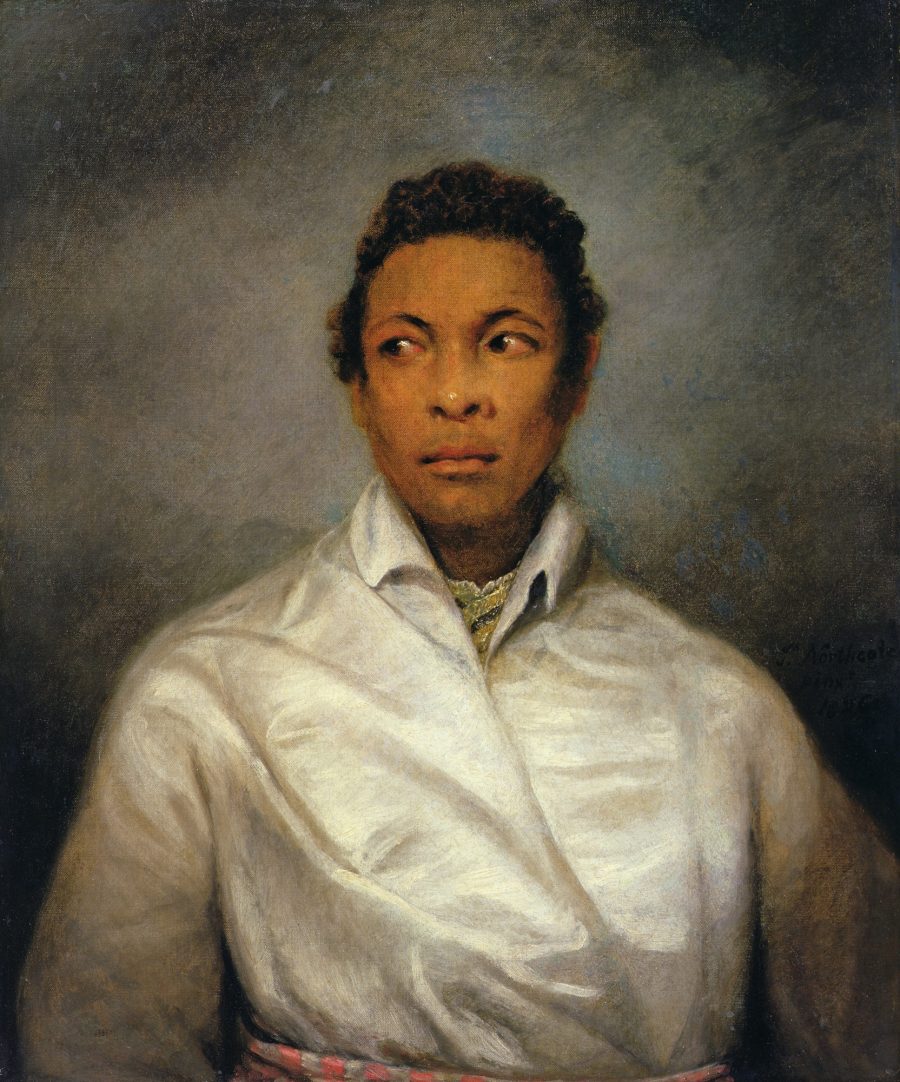

By the Regency era, there were a large number of black people living in Britain, brought about by the empire’s increasing dominance of transatlantic trade in the 18th century, most notably the trade of enslaved Africans. Nineteenth century Black Britons worked in a variety of professions; shopkeepers, artisans, labourers, peddlers and street musicians, amongst others, but the biggest employment sector for both White and Black working class populations was domestic service. Despite the diversity of occupations held by Black people in Britain at the time, the role of domestic servant is by far the most frequently depicted by artists of the period. Although very rarely documented, there are some of these servants who were able to rise in the ranks and resist oppression and anonymity…

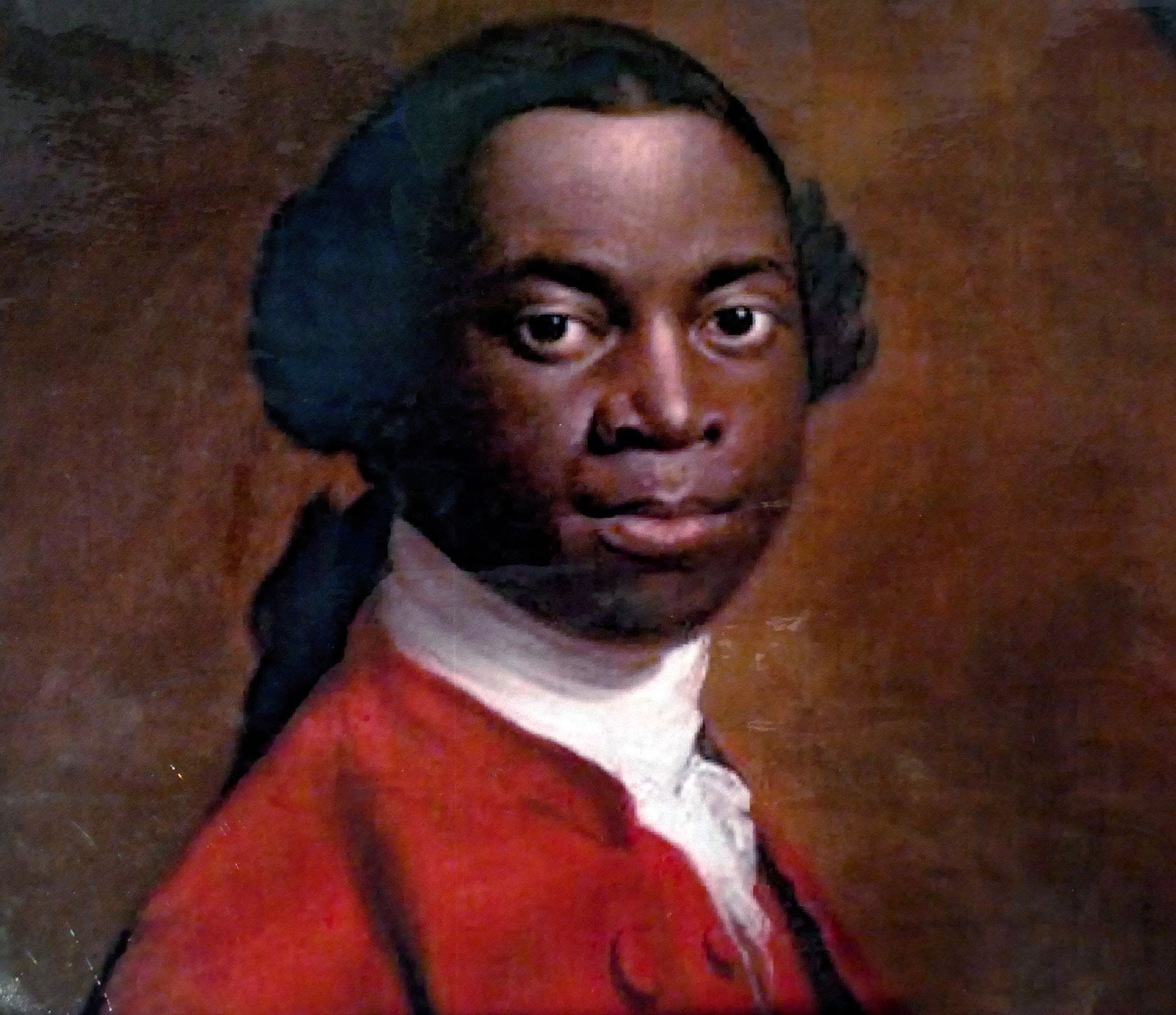

The portrait above, painted in the 1770s, may be of Francis Barber, a Jamaican manservant of author Samuel Johnson in London who was born on a ship transporting slaves from Africa to the West Indies. While he was effectively Johnson’s slave, though the status of slavery was ambiguous at the time, Barber notably assisted in Johnson’s revision of his famous Dictionary of the English Language and other works. Johnson made Barber his residual heir, with £70 a year (equivalent to £9,000 in 2019), which enabled him to open a draper’s shop. Though Barber was essentially an enslaved person for much of his life, which cannot be equivocated, he climbed his way into a more comfortable station, thereby making himself somewhat of a role model for others wishing to one day do the same. Other records show for example, that at the end of the 18th century, a Cesar Picton in Kingston-upon-Thames went from slave to tradesman to gentleman as a coal merchant and property owner, and in Nottingham, George Africanus, started up an employment agency for servants.

The character of Bridgerton‘s Will Mondrich was based on real-life boxer Bill Richmond, a black slave who fought alongside the British during the Revolutionary War. He later moved to England where he became one of the world’s most famous bare-knuckle boxers. An articulate, respected man, he was invited to act as usher at George IV’s coronation.

While these success stories of Black individuals were rarely documented, much less celebrated, there was another picture of the Black presence that was given preferential treatment on the Imperialist agenda and widely communicated in Europe.

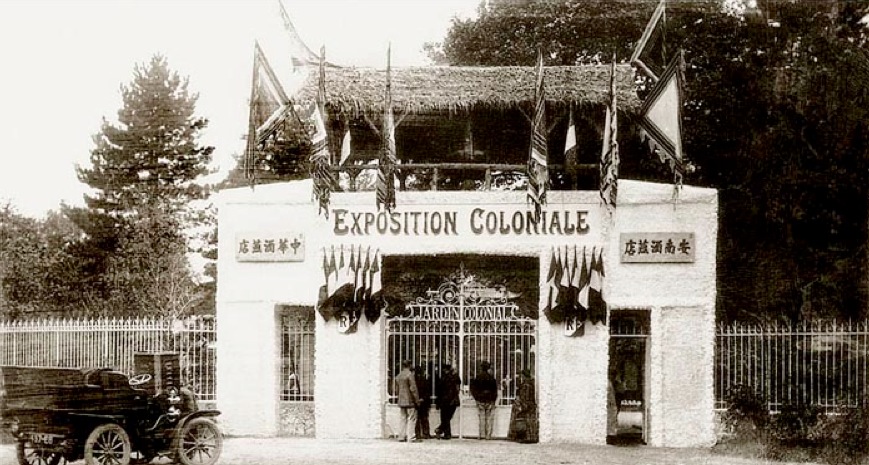

More than thirty-five thousand men, women and children left their homelands for major cities like Paris, London and Berlin during the high noon of Imperialist Europe and took part in ‘exotic spectacles’ – what we can only refer to today as the equivalent of a human zoo. Entire families were recruited from the colonies and placed in replicas of their villages, given mock traditional costumes and paid to put on a show for spectators. An opportunity to demonstrate the power of the West over its colonies, the expositions became a regular part of international trade fairs and encouraged a taste for exoticism and remote travel. Europeans gawked at bare-breasted African women and were entertained by re-enactments of “primitive life” in the colonies. Here, anthropologists and researchers could observe whole villages of tribespeople and gather physical evidence for their theories on racial superiority and the invention of the savage.

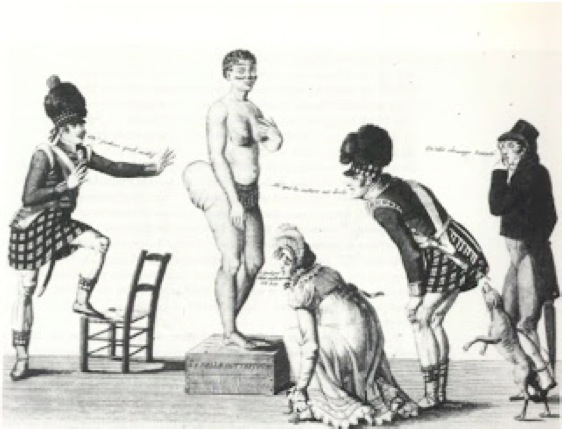

Sarah “Saartjie” Baartman, a 20 year-old girl from South Africa, was emblematic of the dark era that gave rise to the popularity of human zoos. She was recruited by an exotic animal-dealer on location in Cape Town and traveled to London in 1810 to take part in an exhibition. The young woman went willingly under the pretence that she would find wealth and fame, only to find herself being exhibited in cages at sideshow attractions. Read more about Sarah’s story and Europe’s human zoos here.

While uncovering the hidden history of Black excellence, what must never be forgotten is the mountain of injustice and suffering that was climbed for a few to find success. For it’s not the fact that Black individuals were able to reach the highest levels of society that should surprise us, but the courage and perseverance it took to get there in the face of impossible adversity. Here’s hoping we might see more of that journey addressed in season 2 of Bridgerton, and in the meantime, if there are stories you’d like to add that we missed (and there must be) please guide us and our readers to their stories in the comments.