In pursuit of the African American story abroad, we often look to 1920s Paris, where jazz was first introduced to the French and Black culture was embraced with open arms. It’s a more familiar story than the one about Soviet Russia opening its doors to thousands of Black Americans in the 20th century, where they found social freedom, acceptance and economic opportunity. Under Stalin’s de facto policy of ethnic cleansing, it’s hard to picture the USSR as any kind of paradise for persecuted minorities, but in stark contrast to the trauma and systemic oppression that people of colour had long-faced in the many parts of the western world, Mother Russia poised itself as a beacon of equality, ahead of the historical curve. Turning to a lesser-known chapter of American ex-pat tales, this is the murky, hidden history of an unlikely regime that despite its pernicious past, also tried to make it “great to be Black in the USSR”…

A brief recap. In 1865, slavery was abolished by United States law, leaving behind a form of societal chains in its wake, otherwise known as Jim Crow Laws, which still denied Black citizens freedoms like voting, running for office, equal education and employment opportunities, intermarrying between racial groups, and generally sharing the same rights and everyday facilities as Whites. It wasn’t long before African Americans started looking elsewhere for advanced education and work opportunities. Many as we know, went to Europe, but some ventured further East…

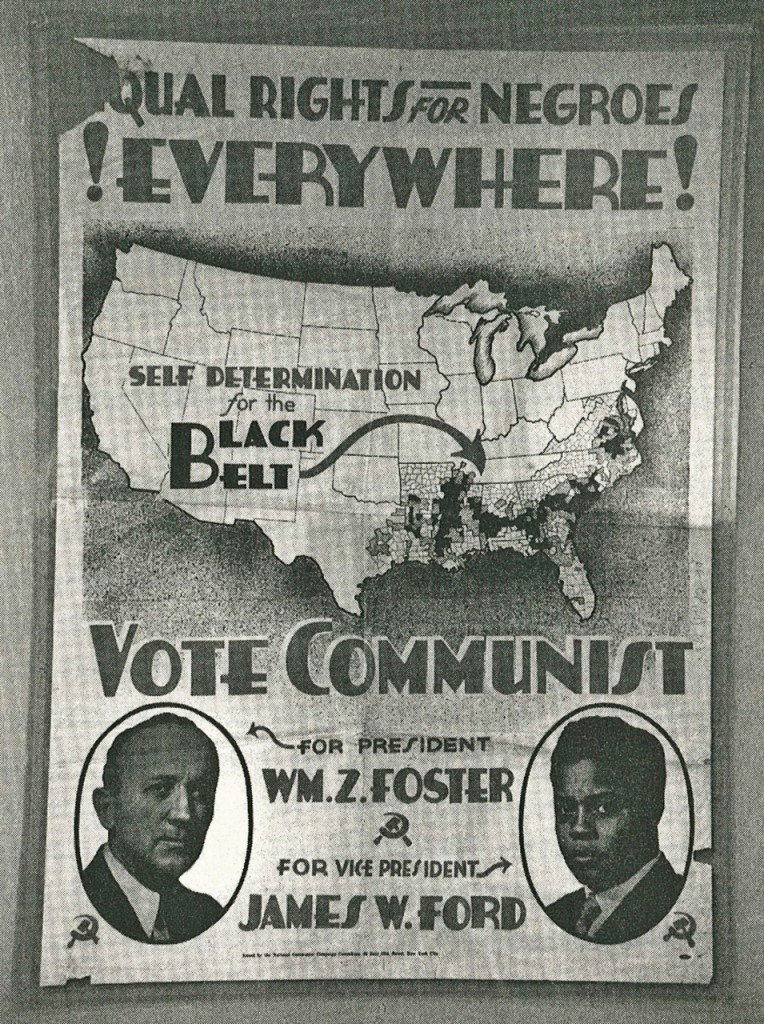

Enter the USSR, an institutional platform sympathetic to the plight of Black Americans, sending hope from afar that a world devoid of racism might just be possible. The Soviet experiment started recruiting African Americans to the Communist party as early as the Great Depression. The timing is worth noting because the worldwide economic crisis had also hit Russia hard. A lack of modernisation crippled its agricultural and industrial sectors, which meant they desperately needed to modernise – and fast.

Among the first African Americans to arrive in Russia after the revolution were specialists in the spheres of industrial production and agriculture, particularly in the cultivation of cotton – the very industry that had prolonged slavery and effectively caused civil war in America. But over in Russia, their agricultural experience born out of forced labour was considered a vital contribution to the economic development of a new state, and most importantly, one they could now actually be paid for, with decent wages too.

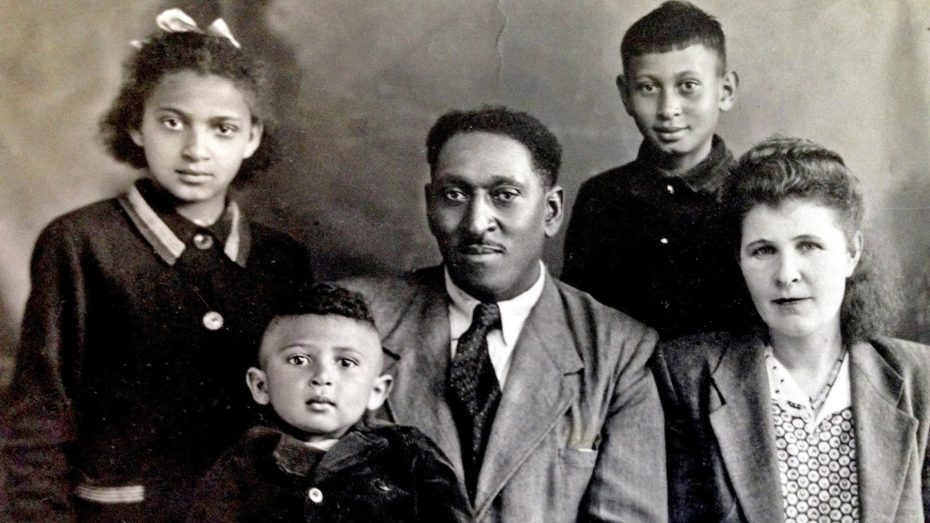

From the 1930s, many Black American émigrés were able to find jobs quickly in the USSR and assimilated into Russian society, facing fewer social barriers. They could marry interracially, learned to speak Russian and to read Pushkin and Dostoevsky. No longer excluded because of their skin colour, they even found opportunities within the film industry. The Soviet Union went to great lengths to ease any lingering hesitancy about how they would be received in Russia by releasing state-sponsored films and short stories that reinforced themes of racial tolerance.

One example of this is the USSR’s most successful of all time – and Stalin’s “favourite movie” – Circus (1936), which depicts a single White mother with a Black child who flees racism in America and follows the circus to Russia where they find acceptance in the USSR. At its climax, the cast sings to her baby in every language of the USSR…

The film has long been considered a notable form of Soviet propaganda. The trauma of slavery and continued injustice of American segregation made rich pickings for Communist agenda, which played heavily on its official stance against racism to denounce western capitalism, but Soviet antiracism also gave African Americans the ability to momentarily step beyond their skin for the first time. Actors and filmmakers could position themselves in front of the camera and have more say in their narrative. These liberties sharply contrasted with early Hollywood, where the Black presence was virtually non-existent and White actors appeared on screen in blackface. Dozens of African American filmmakers and actors moved to Russia and stayed there, where many of their descendants still live.

While rumours grew of a secret genocide of the Ukranian people, the Soviet experiment offered a cathartic experience for descendants of American slavery. It was an alternate reality, where racism –and gender discrimination– were strictly not tolerated, even punishable by state law. Case in point: when Henry Ford sold his model-T assembly line to the Soviet Union in the 1930s, among the thousands of American factory workers that immigrated to the Soviet Union was Robert Robinson, a skilful engineer, and the only person of colour of the Ford recruits. When he was violently beaten by two White American co-workers shortly after his arrival, the Soviet press championed Robinson’s case as an example of American racism and his attackers were promptly kicked out of the country.

With his strange and new-found fame, Robinson tentatively stayed on in Russia, but lived carefully under Stalin’s paranoid regime. Meanwhile, during the Great Purge of the 1930s, the vast majority of Ford’s American workers ended up as political prisoners in the Gulag where they were worked to death. (There’s a book about the incident, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia by Tim Tzouliadis).

While darker truths remained hidden behind the smokescreen of the Iron Curtain, Soviet secrecy managed to keep African Americans nevertheless intrigued by Russia’s core socialist ideologies. In the mid 20th century, Marxist intellectual circles in New York City briefly exposed many prominent African American artists and writers to Communist groups, including the great James Baldwin and Richard Wright. Ever suspicious of treacherous ties to Soviet Russia during the McCarthy era, the FBI kept Wright and Baldwin under constant surveillance throughout the Cold War.

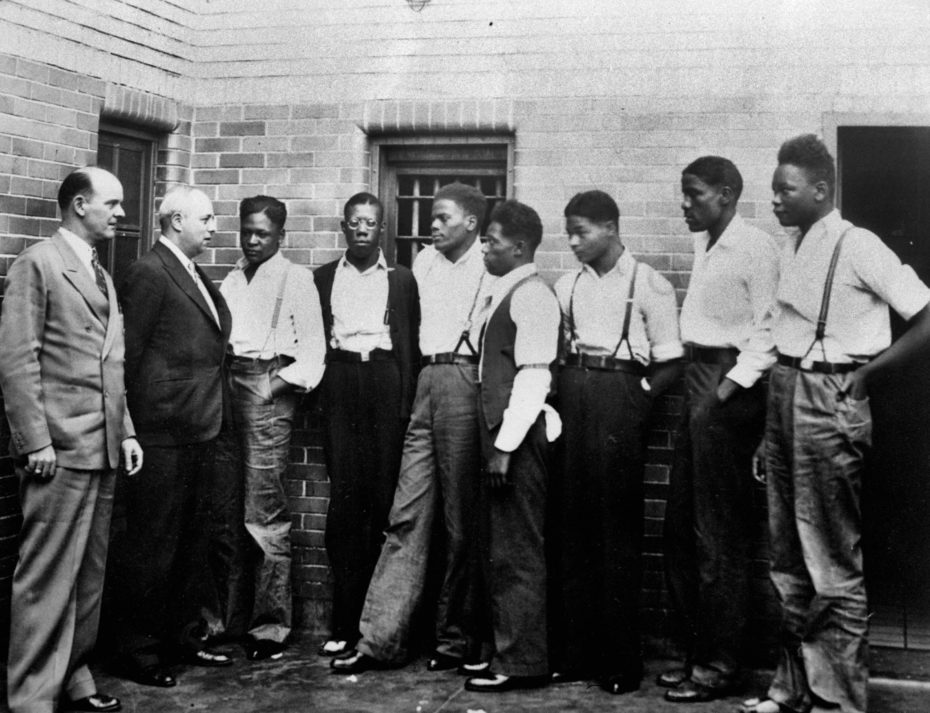

Wright had joined the American Communist party in the 1930s after it funded the legal defence of nine Black teens known as the “Scottsboro Boys”, who were wrongly convicted of rape by an all-White jury in Alabama. Before moving to Paris, both Wright and Baldwin cut ties with the party, recognising its oppressive and dangerous undertones, but the FBI still kept extensive files on them for years.

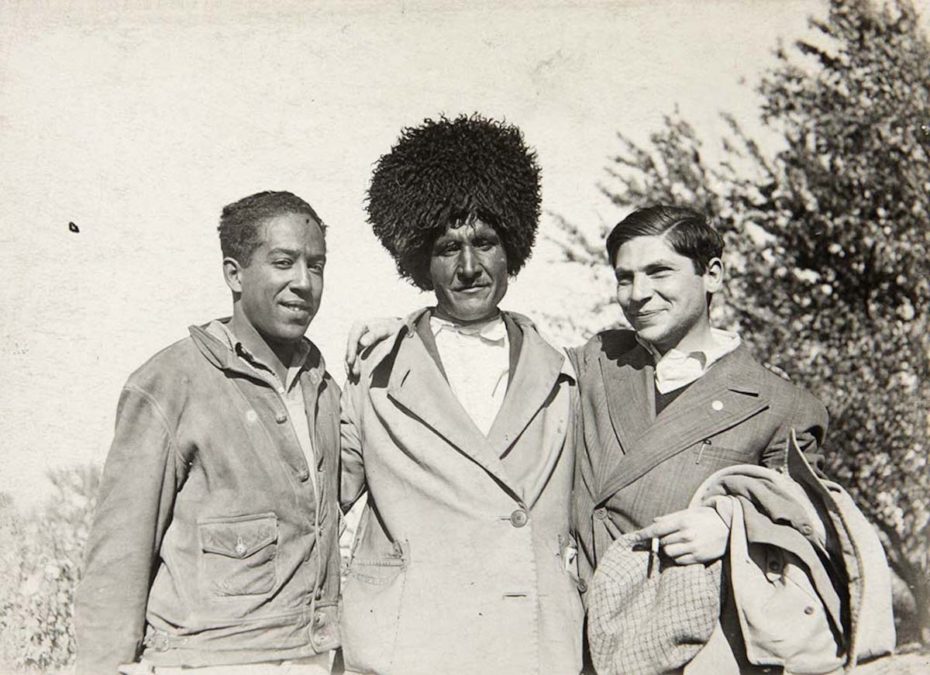

During the Harlem Renaissance, other writers including Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Dorothy West had spent time in Russia through the efforts of an international organisation called Comintern, which advocated communist ideologies abroad in the 1920s and 30s. In principle, antiracism was a quality of a good Soviet citizen and Russia’s lack of involvement in the colonisation of Africa also made it an attractive ally to the Black cause. Geography can take a lot of the credit for isolating Russia from Africa during the slave trade, excluding Soviets from the colonial narrative that Blacks were inferior to Whites. Russians looked towards Africans with curiosity rather than instinctual contempt and hatred. As the Soviet Union backed African nations in their postcolonial fight for independence from western control, thousands of young students from the continent were invited to the USSR on scholarships.

They would learn about the story of Abram Petrovich Gannibal, a prominent African member of the Russian imperial court who started a famed aristocratic Afro-Russian dynasty in the 18th century. After Ottoman forces kidnapped him as a boy from Cameroon, he was sold to a Russian diplomat and “gifted” to Peter the Great, who publicly adopted and freed him. Abram became a military engineer, a high-ranking general and a nobleman. He is also a maternal great-grandfather to the famed Russian poet Alexander Pushkin.

Soviet Russia, however, was far from a paragon of minority rights. The USSR had an infamous reputation for exterminating and repatriating ethnic minority groups, deporting millions of starving working class farmers throughout the 1930s as “enemies of the people”. Indeed, it would eventually be revealed that the Soviet Union would eventually had its own form of slavery.

In the 1960s, as more foreigners; Africans, Asians, Arabs and Latin Americans; immigrated to Russia, the antiracist Soviet rhetoric began to hollow.

Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, what can history teach us? Despite the USSR’s undeniably dark and tragic past, Soviet antiracism can still serve as a worthy bases for historical reflection. It’s inconsistent with the brutality of an oppressive regime, but to dismiss this part of the narrative entirely, and file it away in the archives as a textbook example of misguided propaganda may be a lost opportunity to recall a moment in time when humanity may have also been on the right side of history.

We’ll leave you to read between the lines of this note-worthy feature on Afro-Russians produced by the state-controlled television network, RT. Like all things funded by Putin’s government, it should be taken with a pinch of salt…