The Victorians loved their secrets. They hid them in the details but wore them on their sleeve with the help of a few small but elaborate accessories. The nosegay, also known as a posy or a “tussie mussie”, was one of the more discrete lady gadgets of yore that had multiple uses…

For one, if she was unfortunate enough to be born before the revolution of proper sanitation, the nosegay was to a lady what a mask is to the Covid-19 generation today: essential. A small portable bouquet of flowers held together by a funnel-shaped posy holder pinned to one’s dress or attached via a delicate chain, would not only help camouflage the unpleasant smells of the sewage-ridden streets, but also mask one’s own potentially-embarrassing odour during a time before daily bathing was encouraged. The term nosegay arose in fifteenth-century Middle English as a combination of nose and gay (the latter then meaning “ornament”), hence, an ornament that appeals to the nose or nostril. As early as the 1500s, this was its original and practical use, but in the 19th and early 20th century, the nosegay found a more covert and communicative role for eligible young ladies and their gentleman callers.

The use of flowers as a means of secret communication bloomed alongside a growing interest in botany, particularly among women, for whom plant collecting became a highly desirable pastime, encouraged by fashionable ladies magazines and periodicals (see: Botany and the forgotten sexual revolution).

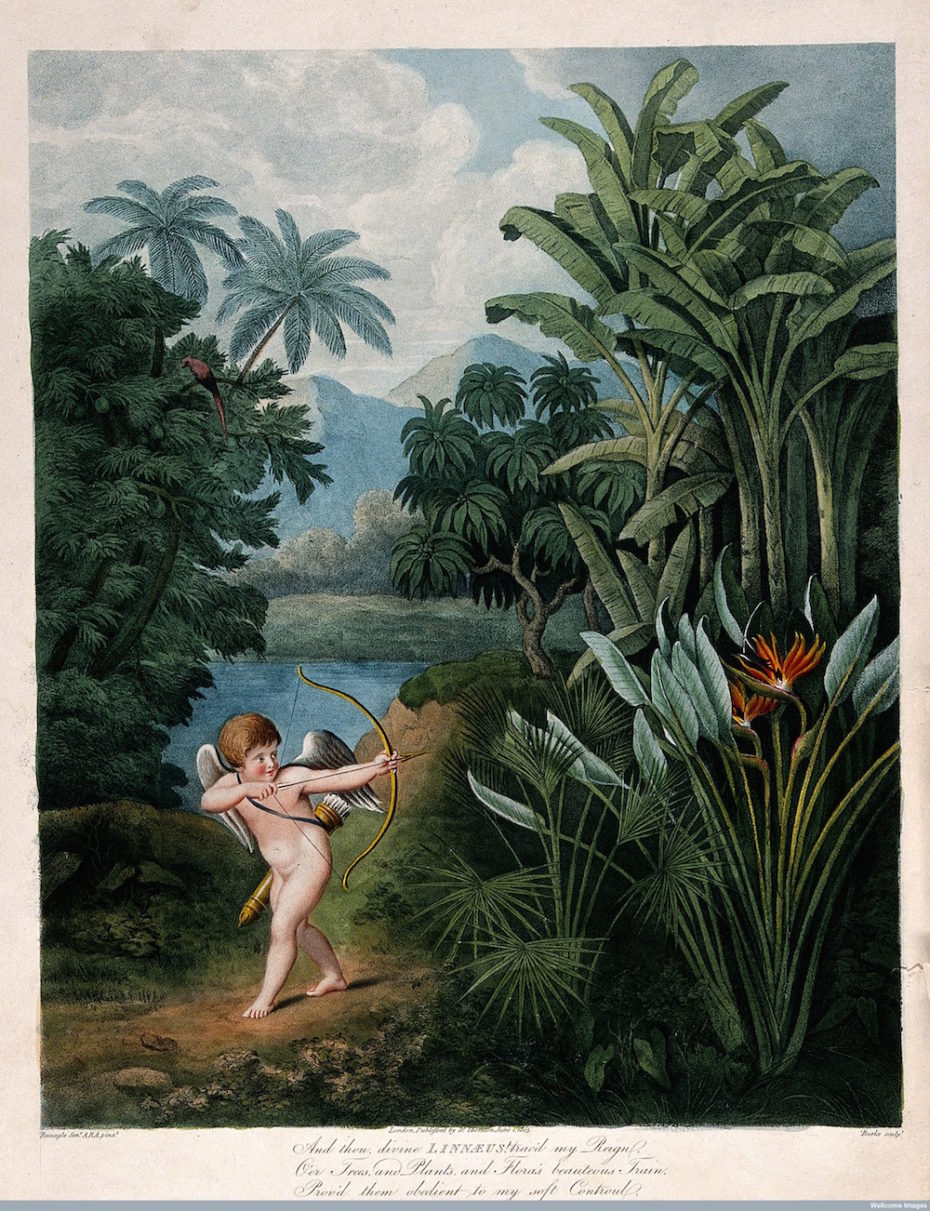

Beginning in the late 18th century, a new wave of Enlightenment botanists had sexed up the study of plants, going as far as to juxtapose our own reproductive systems with plant anatomy, comparing the stamen to a man’s phallus, the style to a woman’s intimates, even the plant petals to a bed and the leaves to the bedroom curtains.

Carl Linnaeus, the great Swedish botanist, identified pollen as the impregnating male sperm that could be carried “promiscuously” in the wind. He described female plants as either virginal or promiscuous flowers that exude a seductive scent when they’re ready to mate, triggering the birds, bees and butterflies to join in on celebrating her nuptial rites.

Conservative organisations didn’t like the direction that botany was heading in and by the early 19th century, there was a strong counter movement underway to censor botanical textbooks for women. But of course, like most things forbidden, the seduction of botany only intrigued educated liberal females further. It was around this time that the nosegay reached its peak as a fashionable statement piece to express a woman’s life status or inform male suitors of a her acceptance (or refusal) of their courtship.

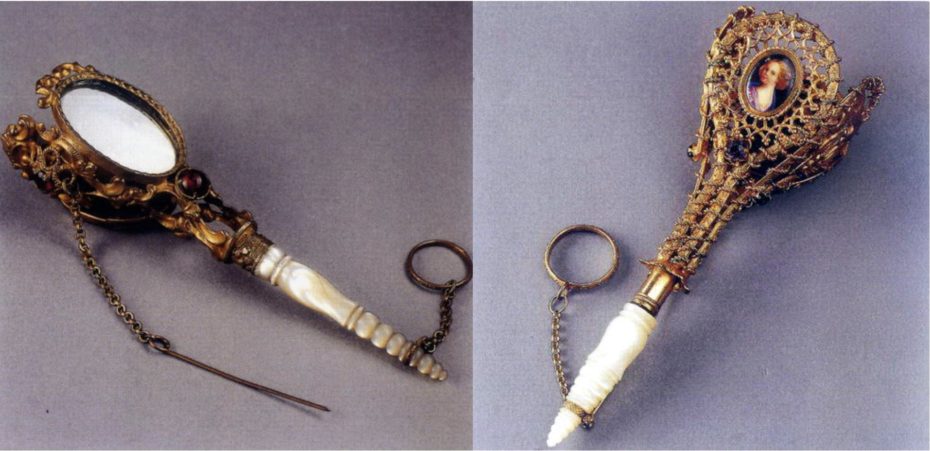

If a lady received a nosegay or a tussie mussie from a gentleman caller, she had to be careful about how she wore the flowers on her dress, which was made possible thanks to the posy-holder, or the “port-bouquet” as it was known in France (Porte – to wear, bouquet – a bouquet). The closer she pinned the flowers to her heart, the better chances her suitor had at winning her over. The posy holders, crafted in decorative floral shapes, were created to keep delicate and expensive silk dresses protected from water droplets.

The handle of the posy holder bunched the wet stems of the flowers together and contained a piece of moist moss like a sponge, wound around the base of the bouquet stems (“mussie” refers to the moss). Scent-soaked cotton balls were also common, wedged into the posy holders to keep the fragrance strong and some models could even be filled with water.

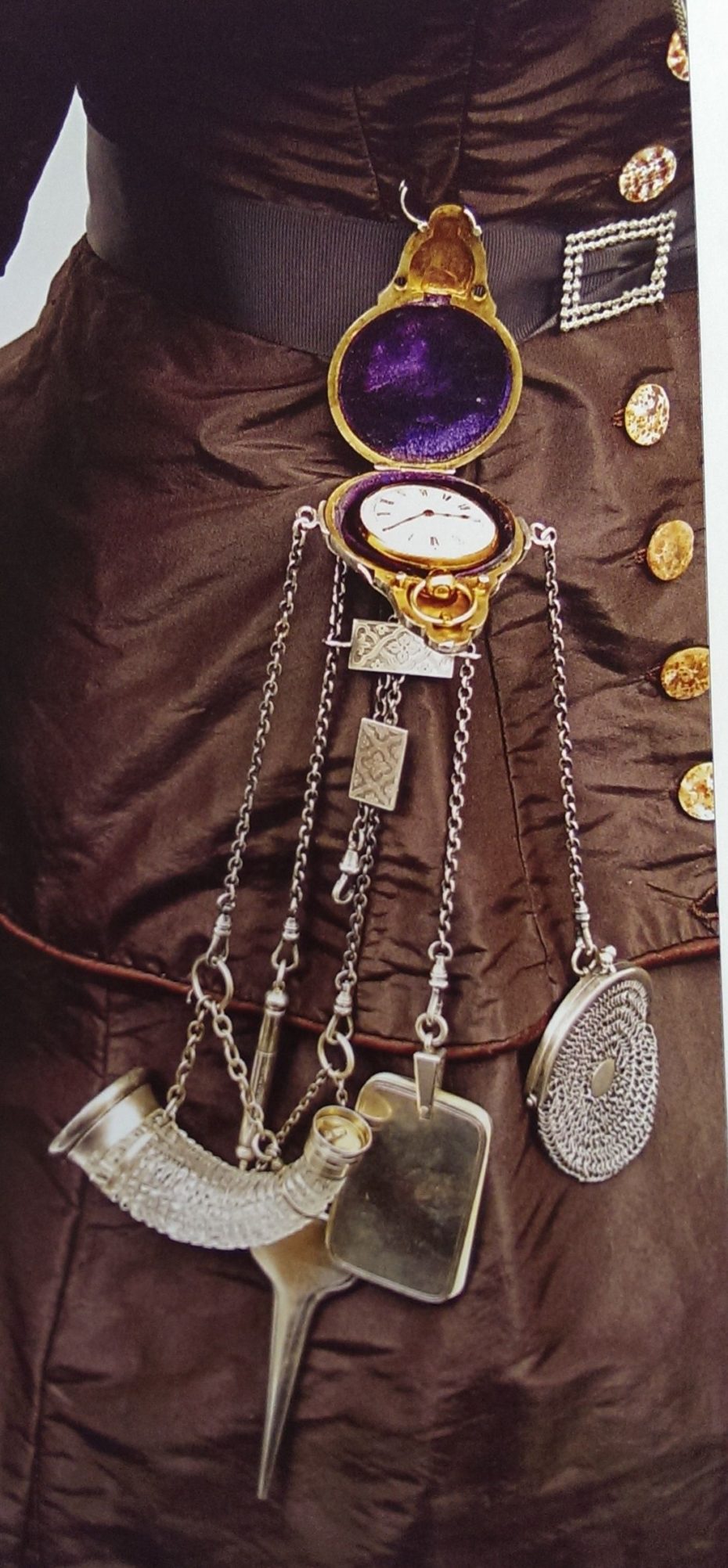

At a formal occasion, when presented with a tussie mussie (as it came to be known in Victorian England), the posey holder also allowed a lady to keep the flowers suspended from her hand using a chain, so that she was free to dance unhindered. Along with dance cards, they were one of the items that might typically hang from a lady’s chatelaine, the inside out handbags of yesteryear.

And like the chatelaine, the design of posy holders could be astonishingly ornate and elaborate for such a tiny accessory. Adorned with precious metals, glittering stones, pearls, shells; even mirrors and miniature paintings, they were flashed around the courts of Versailles, Imperial Russia and 19th century China but most notably in Victorian England, where they became the ultimate fashion fad.

With the rise of superstitious beliefs surrounding ‘exotic’ medicinal plants introduced by colonial explorers that could ward off diseases, some designs were inspired by containers used by alchemists in the Middle East, or more romantically, inspired by Ottoman Turkey, where the language of flowers finds its roots. The cornucopia design was the most common but some more practical models came with built-in tripod legs for resting the small bouquet on a table, turning it into a miniature vase at home.

Specific floral arrangements were used as a form of self-expression and often exchanged to send coded messages that could not be spoken aloud in polite society. For example, the mimosa, whose leaves close at night, or when touched, represented chastity. The deep red rose and its thorns symbolised an intense passion, while pink roses implied suggested something closer to a passing fancy.

“Talking bouquets” could contain numerous hidden meanings or compliments waiting to be deciphered by impressionable young debutantes and floral dictionaries became essential reading (similar to the coded language of hand fan movements). We’ll leave you with a few useful translations for a crash course in the secret language of flowers…

White rosebud: a heart untouched by love

Baby’s Breath: Everlasting Love

Calla Lily: Magnificent Beauty

Camellia: Perfected Loveliness

Daffodil: Unrequited Love

Forget-me-not: Memories

Gardenia: Secret Love

Gladioli: Sincerity

Jasmine: Cheerful & Graceful

Lilac: First sign of love

Lily: Purity of Heart

Orange Blossom: Marriage and Fruitfulness

Violet: Modesty

Sweet-pea: goodbye