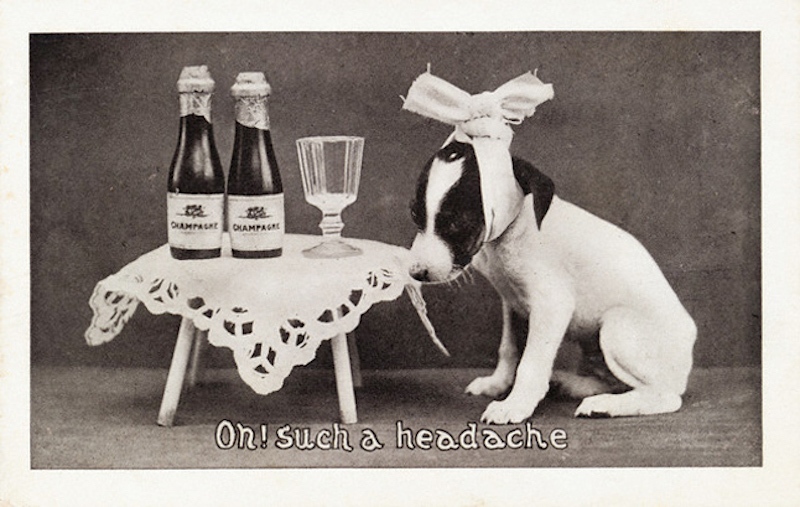

It happens to the very best of us, when the stark light of day wakes us from a slumber with a dry mouth, a sore head and a foreboding sense of shame for our previous night’s antics. For last night, far too much liquor had been consumed, and the party was perhaps a little too hard. As Shakespeare so eloquently put it, “That which hath made them drunk hath made me bold.” As we stumble out from which ever place we had laid ourselves, brief snapshots of the night appear and the unforgiving sense of shame takes over. Some call it hangxiety, others the shameover. And so begins the inevitable conversations with those who were there and who perhaps had a clearer vision of what exactly was said and done, as you retrace your unsteady steps and attempt to decipher who might be owed an apology. Today we can make our clunky excuses through the magic of technology, but this morning-after ritual is one that has been around for centuries – let’s just say that for as long as we’ve had alcohol, we’ve had hangxiety.

Travel back to the first millennium AD, to China, and more specifically to the oasis town of Dunhuang, which welcomed travellers of the Silk Road, taking refuge from the unending desert. The Tang dynasty, which ruled from 618 to 907 AD, is in full swing, sweeping across China, Iran and Turkey and bringing with it a new appreciation for grapes, and consequently, wine.

The Silk Road is thriving, wine is flowing and the opportunities for a good night out are plentiful. Enter the eloquently named Dunhuang Bureau of Etiquette, a convenient service which allowed our disgraced partygoers to purge themselves of their embarrassment, without too much thought. For the Dunhuang Bureau of Etiquette had handily composed a set of drunken apology templates, which officials could have delivered to their hosts, excusing themselves for the previous night’s behaviour. All that was required of the sender was to copy out the helpful little template, enter the host’s name and sign the apology letter, helping ease some of the headache that must have plagued these red-faced revellers.

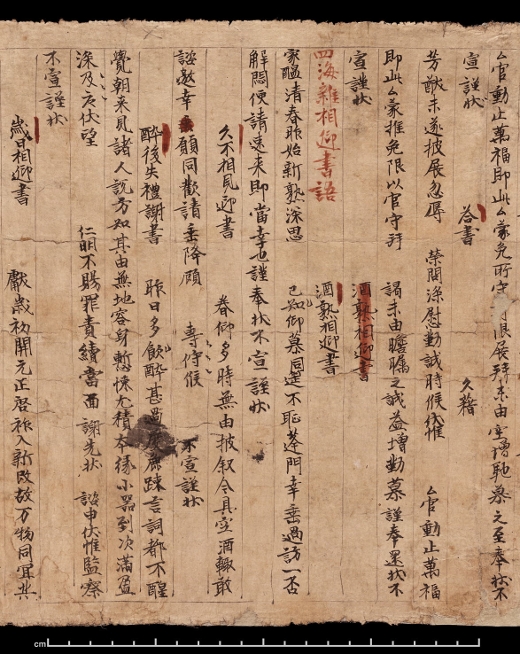

One such example, dated 856 AD, reads:

Yesterday, having drunk too much, I was intoxicated as to pass all bounds; but none of the rude and coarse language I used was uttered in a conscious state. The next morning, after hearing others speak on the subject, I realised what had happened, whereupon I was overwhelmed with confusion and ready to sink into the earth with shame.

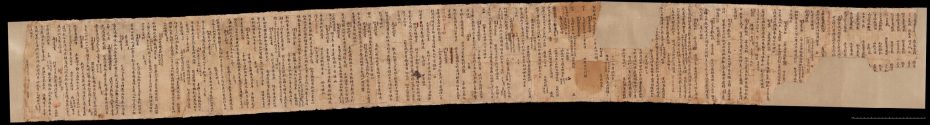

The entire scroll, filled with Form Letters adapted for various situations, can be seen here. The story for how our ancient drunken apology letters came to be found is one that also merits a mention.

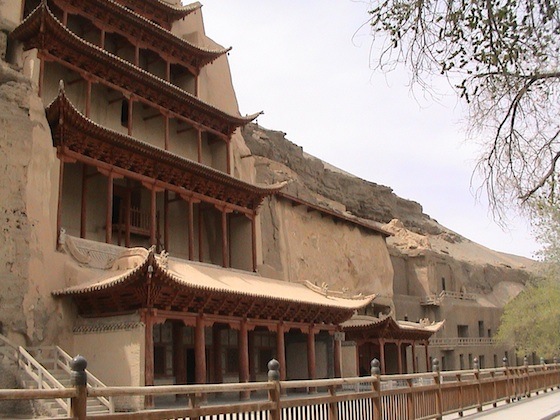

Up until the twentieth century, little was known about the Silk Road. It was only when explorers and archaeologists unearthed the remains of a number of ancient cities, hidden in the desert, that they found a treasure trove of history, made up of sculptures, murals and manuscripts. One of the most notable discoveries was found just outside Dunhuang, in a cave which had been sealed and hidden at the end of the first millennium AD, known now as the Mogao caves.

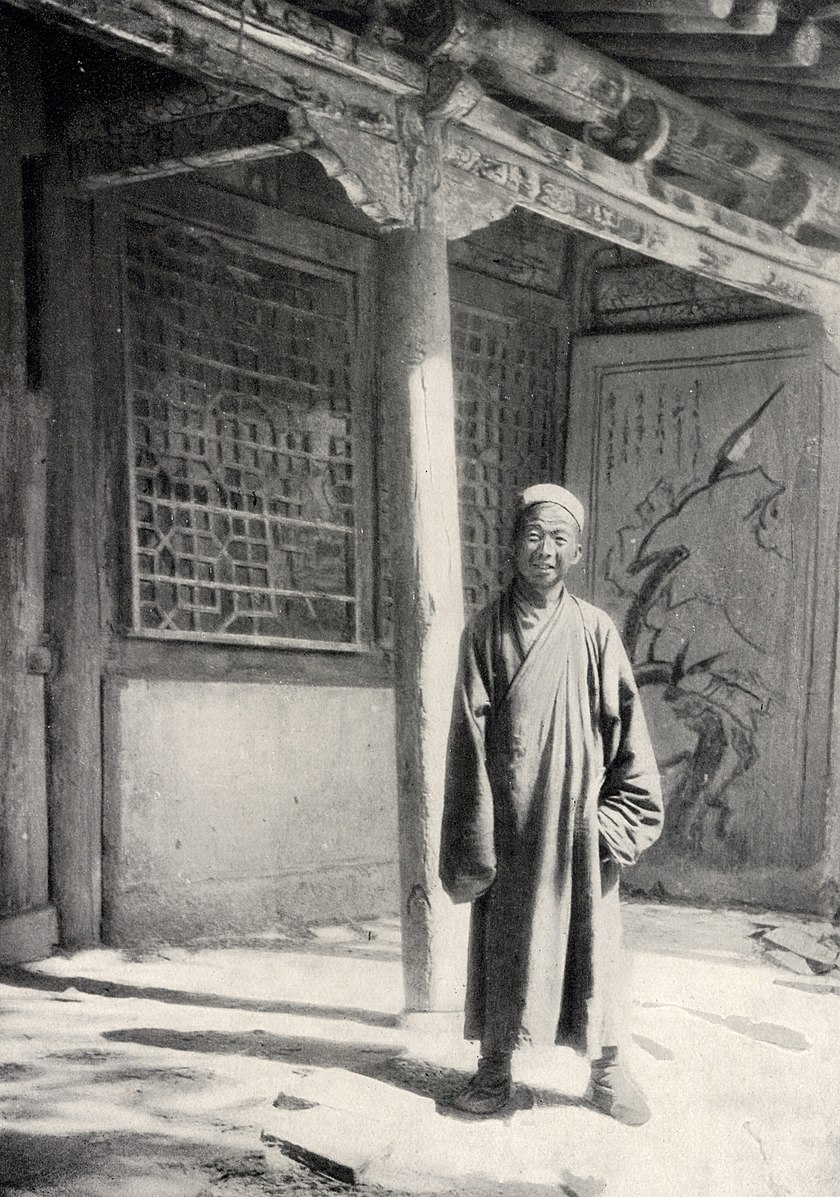

The vital discovery was made by a Chinese monk in the early 1900s, who wished to preserve this spiritual place. He took it upon himself to tend to the cave, meticulously caring for every inch of it and appointing himself as somewhat of a guardian.

One day, the monk observed a crack in one of the cave’s walls and discovered a small, hidden chamber, full to the brim with texts dating from 406 to 1002 AD. Unbeknownst to him, Wang had just excavated a copy of the world’s first dated book Diamond Sutra, which was written in 868 AD and constitutes seven strips of yellow stained paper, pasted together. This however was the very beginning of Wang’s discoveries as he went on to unearth forty thousand manuscripts, paintings and printed documents, which have helped historians to build a rich and enticing picture of the Silk Road’s history. As to why these texts were squirrelled away from prying eyes, the answer is unclear but it is perhaps suggested that the Buddhist monks who did so were wary of an encroaching invasion.

M. Aurel Stein © British Library

Desperate to secure funding to allow him to continue caring for the cave, Wang sold a British-Austrian archaeologist by the name of Marc Aurel Stein, seven thousand of the manuscripts, along with six thousand fragments, and several cases filled with paintings, embroideries and other artefacts. Stein later remarked that the measly sum of £130 which he paid for this incredible haul was one “that will make our friends at the British museum chuckle.” Indeed, this discovery is now considered to be one of the greatest archaeological finds of all time, earning Stein a knighthood but the enduring disdain of those in China.

The collection of work acquired by Stein revealed a world that the West had been oblivious to. The texts were written in Sanskrit, Turkic, Chinese and Tibetan and painted a picture of what it was like to live on the Silk Road during its glory days. Not only were the drunken apologies discovered but along with them, a medley of other documents including slave contracts and police reports.

This remarkable loot is now spread out across the world, displayed in museums in Beijing, Delhi and Paris, while the drunken apology letter finds itself on display in the British Library. A cautionary reminder that one hazy night of your life, might just go down in history in more ways than one. Always drink responsibly!