Pink for girls, blue for boys. Heels for women, flats for men. Corsets for ladies, burly silhouettes for gents? Turn back the clock and you’ll find history is full of contradictions. In fact, until the 20th century, pink was a boy’s colour, high heels were invented for men and yes, they also wore corsets. The infamous lace-up undergarment typically conjures up images of a woman, clinging to a bedpost as the someone behind her yanks with all their strength to get that wasp waist down to eighteen and a half. We might picture the heaving gowns of the Renaissance that required corsets just so a woman could stand upright, or the extreme S-bend Edwardian corsets. But whatever it is you think of when you hear “corset,” it’s unlikely that you think of a man, at all.

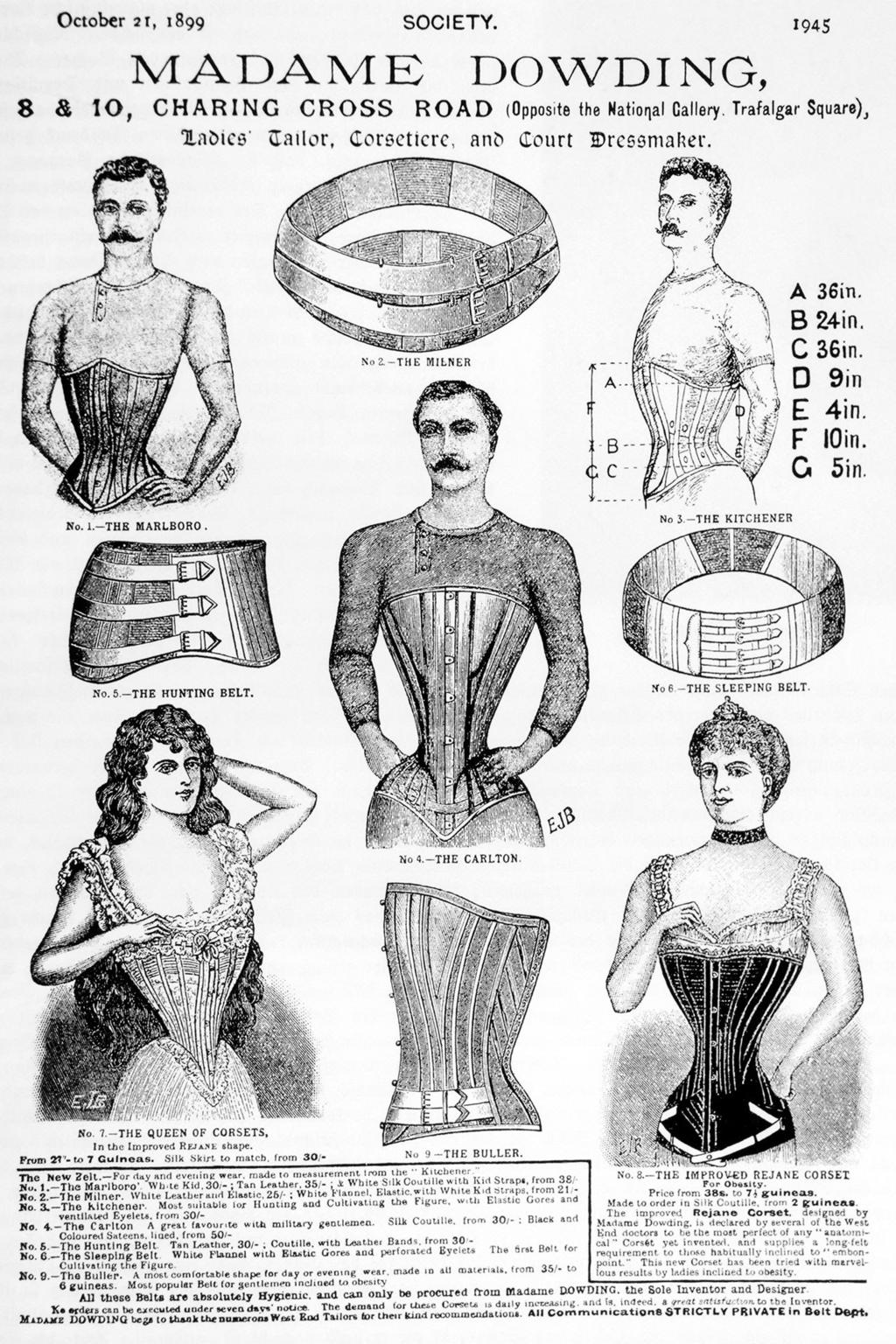

The corset has endured hundreds of iterations from its induction into fashion by Catherine de Medici in the 1500s up until its usage diminished as a result of rations for the second World War. But men have been involved in corsets since corsets were invented. One of America’s founding fathers, Thomas Paine, was a corset maker by family trade. According to research, “Stays or corsets were used in the army (especially among the cavalry), for hunting, and for strenuous exercise, not unlike a weight lifter’s belt today”. Purser Thomas Chew, a 30-year career Naval officer, who fought in the War of 1812 wore his corset to sea. But as history has shown, sometimes function becomes fashion…

“The secret…”, wrote one 19th century Frenchman, “lies in the thinness and narrowness of the waist. Catechize your tailor about this … Insist, order, menace … Shoulders large, the skirts of the coat ample and flowing, the waist strangled – that’s my rule.”

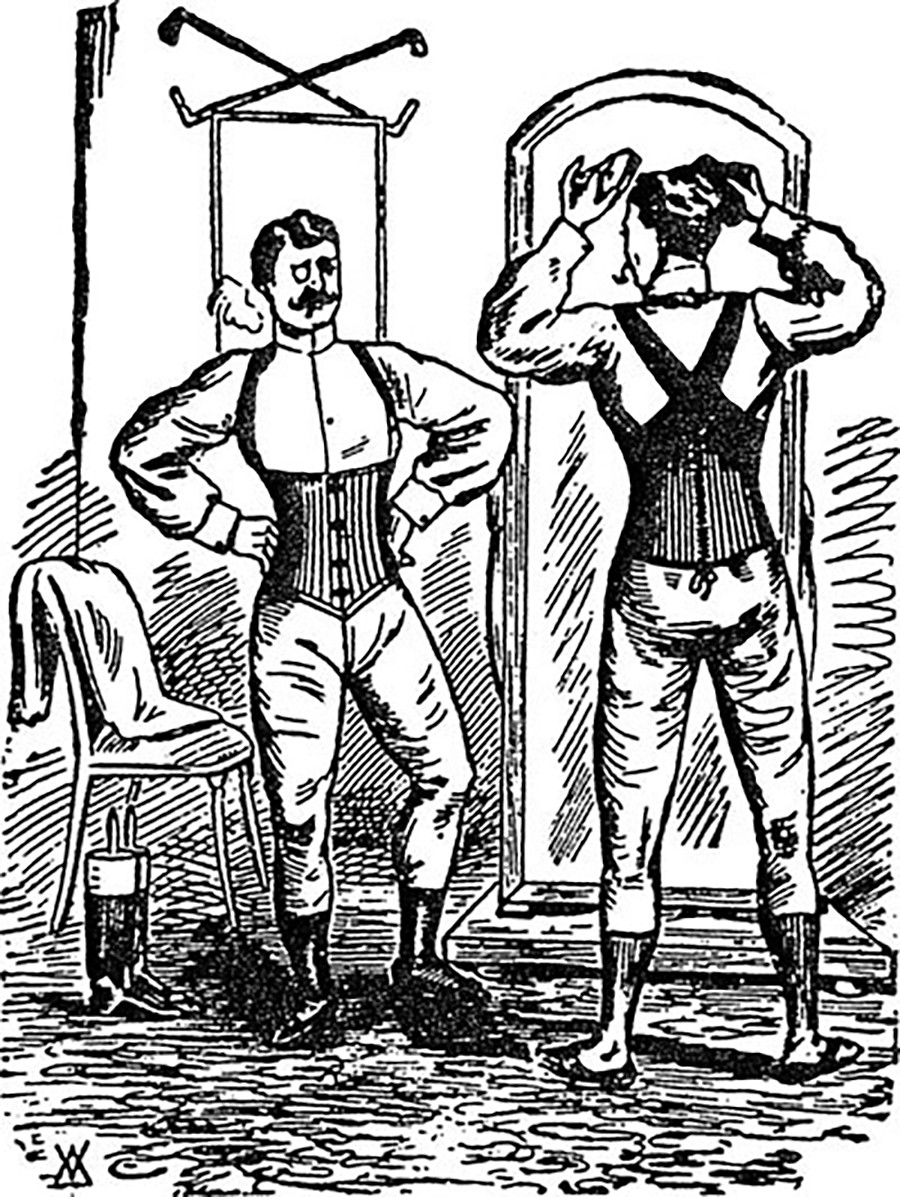

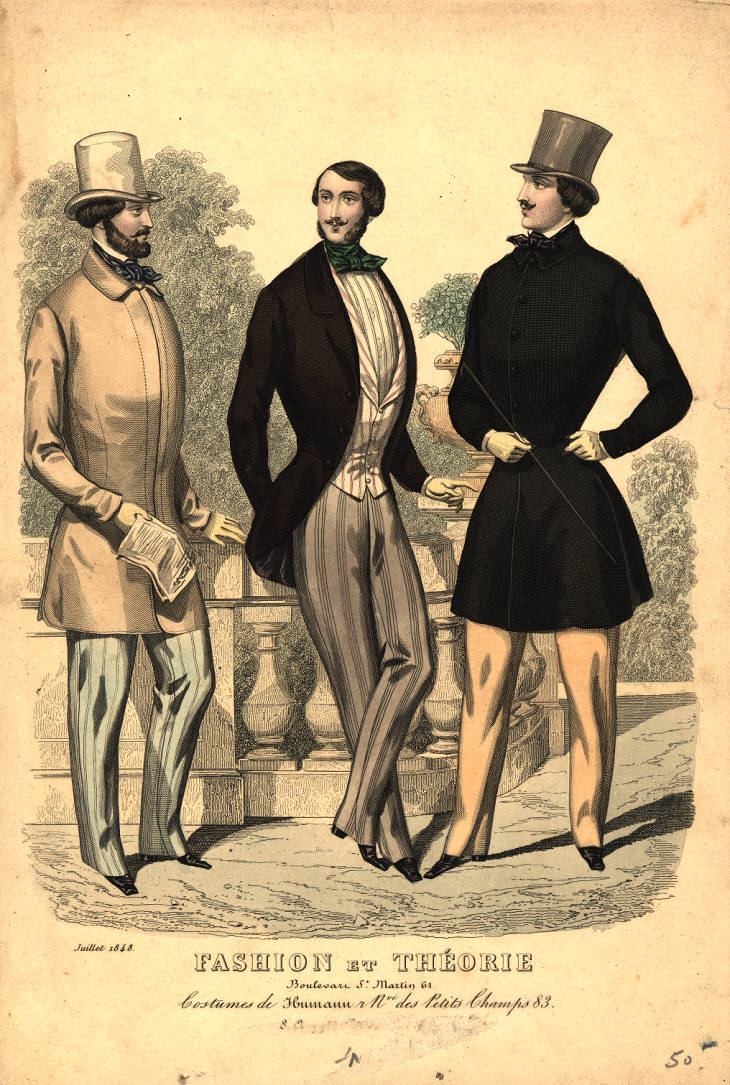

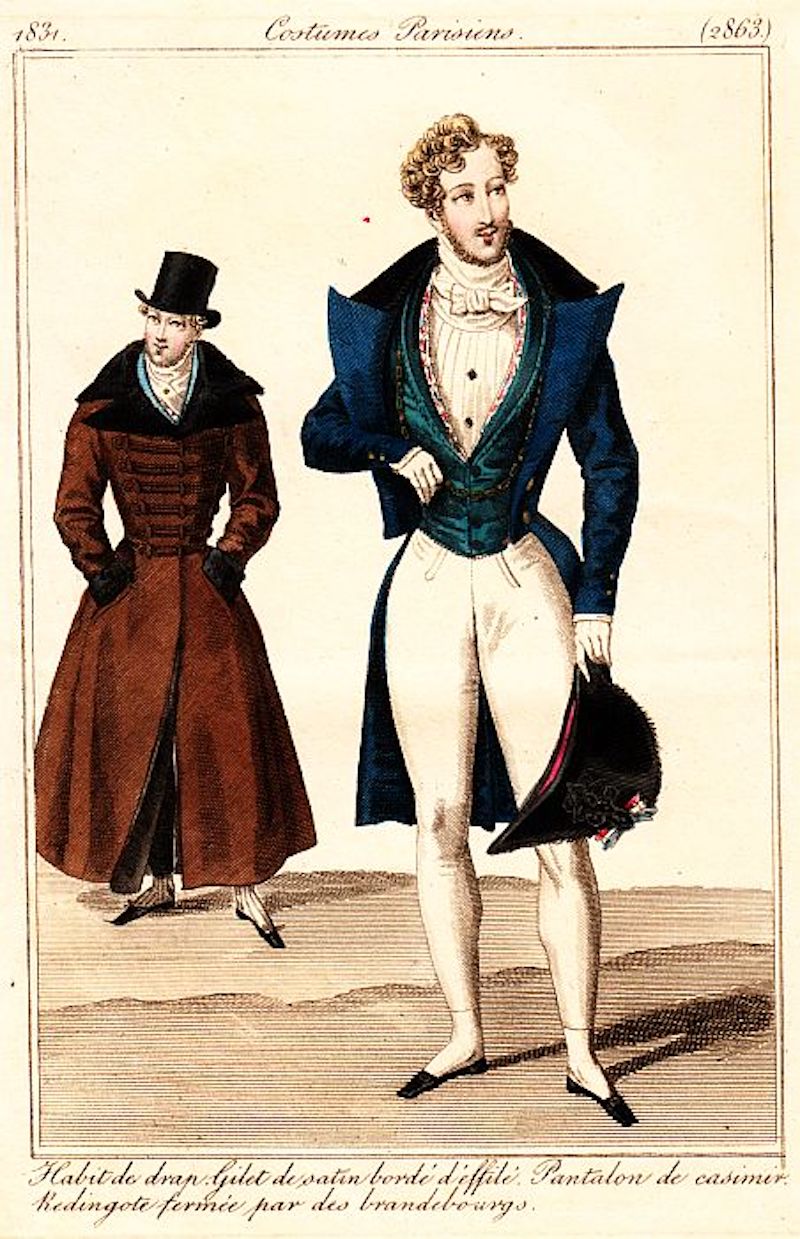

Dandyism is a fascinating era for men’s fashion and became a widespread trend in late 18th – early 19th century Europe, particularly in Great Britain. Dandies strove to imitate an aristocratic lifestyle, placing particular importance upon physical appearance and using refined tailoring to exaggerate the natural figure beneath fashionable outerwear.

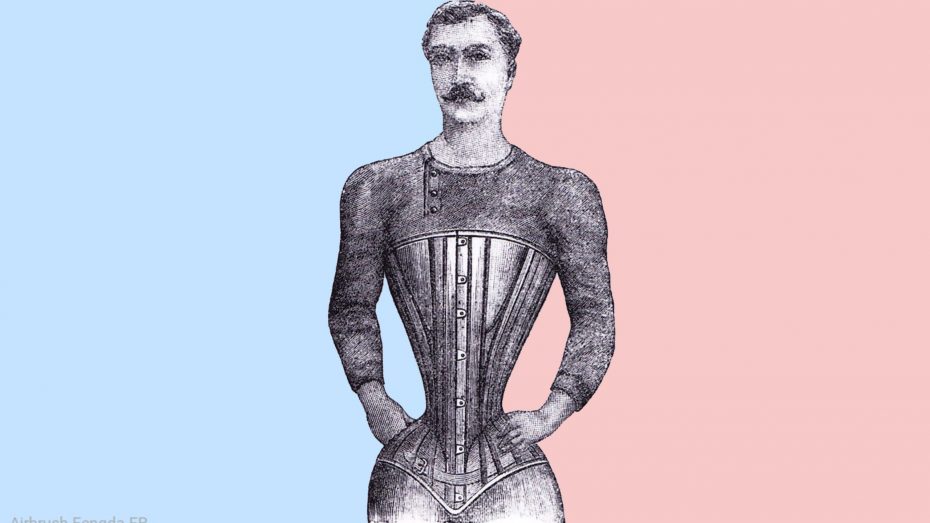

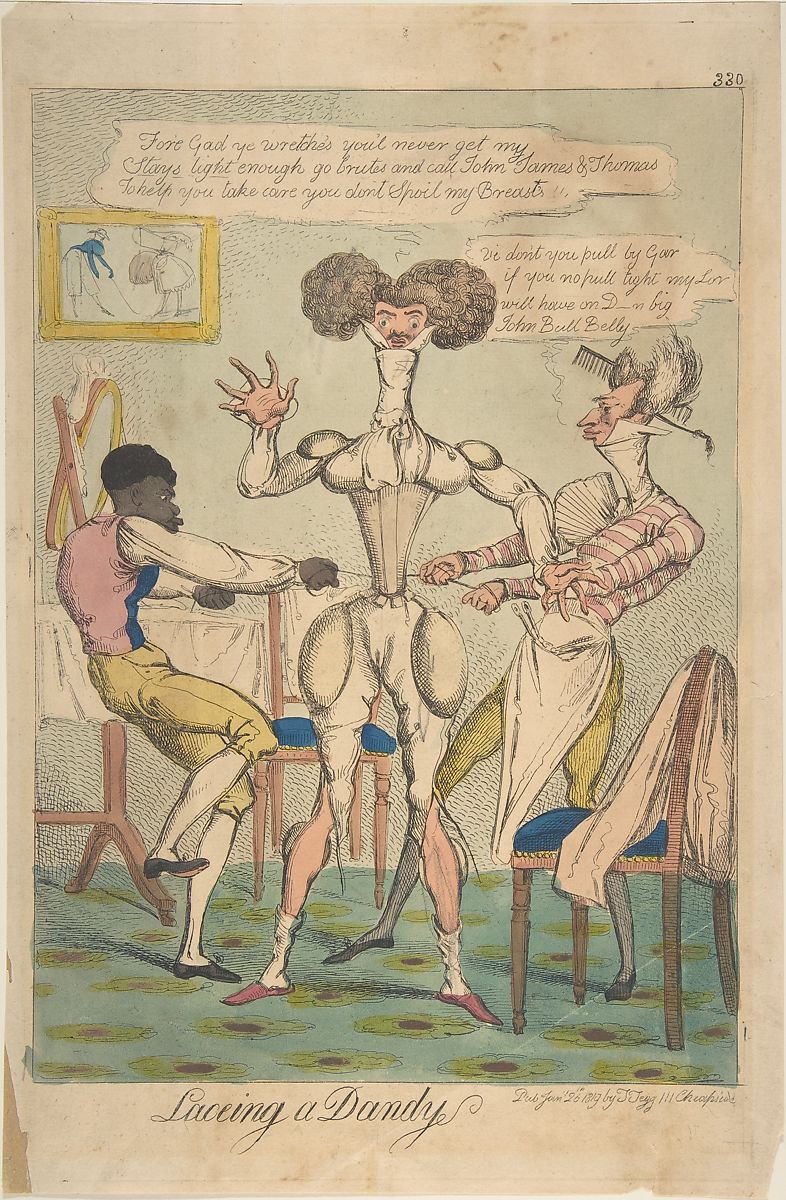

A dandy had a wide arsenal of tricks to enhance his figure, which included adopting fashions that often emphasised feminine characteristics. If he wasn’t slender enough, his underwear might include corsets or stays (boned undergarment), and special pads elsewhere to enhance his chest, shoulders, thighs, shins and buttocks.

One historical fashion curator states, “The breeches in the 18th century were short and stopped right below the knee, so it was desirable to have a nice S-curve to the calves,” Denis Bruna explained, thus the popularity of socks with interior padding. “Around 1820, men wore corsets, certainly for the first time in the history of clothes,” he added, “because it was important to have a very tight and thin waist.”

Preceding the dandy, society knew the “macaroni”, an even more fashion-conscious figure of early 18th century England who had borrowed style notes from the flamboyant male courtiers that once frequented the French courts of Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette. (From a young age, the “Sun King” was a passionate dancer and his love of dramatic artifice was beautifully interwoven into the royal costumes, which included tights and tutus galore).

The “macaronis” got their name from the rising excitement at the time around Italian pasta, which was a then-novel product brought to England by wealthy aristocrats returning from their “Grand Tours” of Europe. Known to converse using a mixture of languages and bilingual puns, a macaroni was a well-travelled male who sported tighter waistcoats, heeled shoes, rouged lips and cheeks, pox patches, powdered wigs, lace cascading from his collar and sleeves with bejewelled fingers and manicured nails. He was said to belong to the Macaroni Club and referred to all things fashionable and contemporary as “very macaroni”. He also gambled a lot, ate very little and generally “exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion”, which ultimately laid himself open to satire.

After the social upheaval of the French Revolution, the dandy brought about a more understated male dress code, but much of British aristocracy still relied on the tailors of Savile Row to give them a silhouette that recalled statuesque Greco-Roman male beauty, even if beneath their clothing, they didn’t quite have the figures to match.

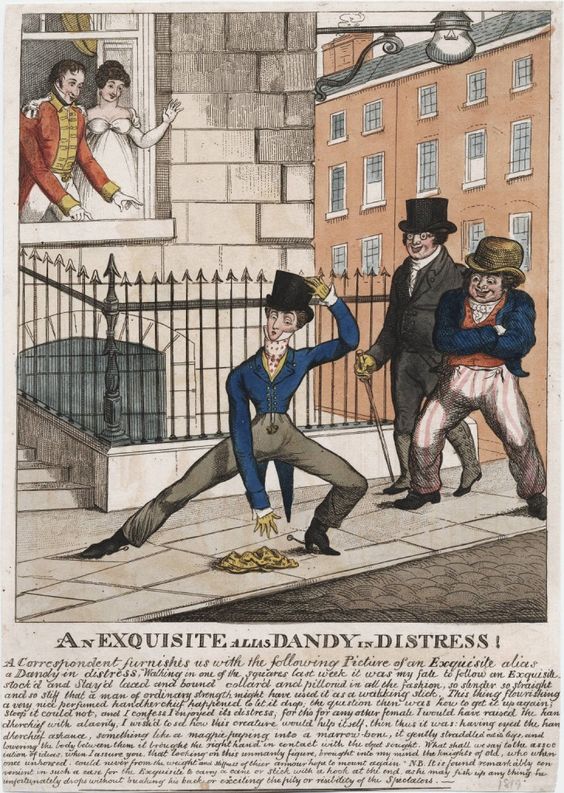

The “redingote,” a Francophile mispronunciation of “riding coat” was a discreet and alternative form of corsetry for men in the 1820s. When it passed from France to England, its popularity remained for about a decade, but like the macaroni, the dandy fell victim to public ridicule.

Caricaturists simply loved to mock them, portraying their style as a symbol of inappropriate bourgeois excess, effeminacy, and possible homosexuality, although modern critics suggest the trend was likely evoked by a metrosexual expression of early consumer capitalism. Feeding into a longstanding rivalry between the English and French, 19th century British humour also stereotyped fashionable French dandies as thin and underfed while contrasting them with the manliness of well-nourished Britons.

Throughout the 18th and 19th century, a historical phenomenon was also brewing, known as the Great Male Renunciation, which would eventually set the tone for menswear for centuries to come. It would see men renounce the desire to dress beautifully or uniquely, losing their zest for fashion and instead, choosing to be more practical, simple and functional. The prominence of the dandy thus diminished entirely after the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, leaving fashion to become a woman’s game. At the same time, women were asking for more rights and gender equality, gradually adopting masculine fashion to express those desires. The women’s rights movement and the threat of role reversal in the mid-nineteenth century increased a need to assert male dominance. With that, stigmas were created surrounding male dandification, and effeminate dressing officially became taboo. Men had essentially abandoned their claim to be considered beautiful and until the rise of the counterculture in the 1960s, the standards for men’s dress went largely unchallenged in the Western world.

Contemporary fashion designers have since attempted to revive the men’s corset, such as Jean Paul Gaultier and Alexander McQueen. In 1995, Mr. Pearl, a noted corset maker and performer, famously walked in the McQueen Spring show sporting an 18 inch trained waistline. With the likes of Dita Von Teese and the Royal Opera House as clients, Mr. Pearl not only devoted his craft to creating corsets, but he also stays corseted 24/7.

“My work is not about being fashionable. I do not follow fashion at all. I’m interested in an ideal, a kind of expression of elegance, which really has nothing to do with fashion.”

–Mr. Pearl

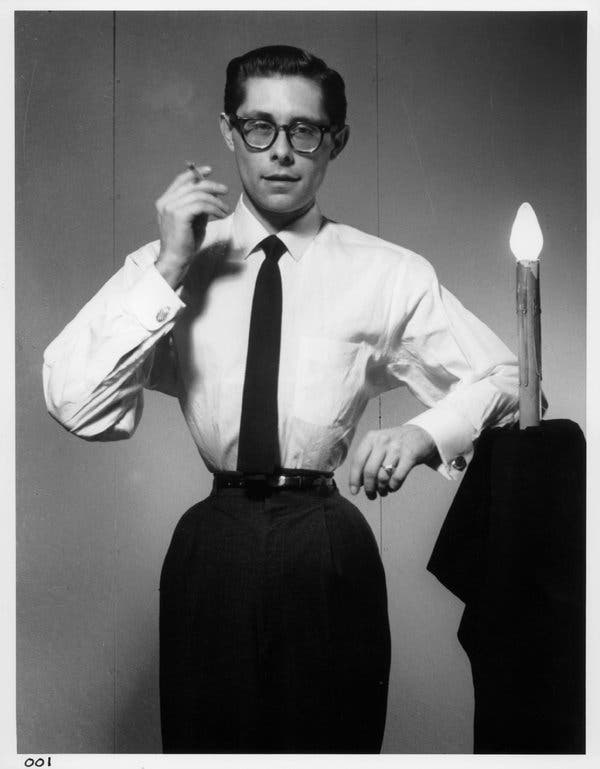

Mr. Pearl was largely inspired by the extreme body modification artist Fakir Musafar, pictured below in 1959, who specialized in extreme body modifications, which he called “body play.” Still, the 20th century wasn’t quite ready for the male corset.

Of course for women, the corset comes with enough controversy, having historically signified both beauty and oppression. But as Generation Z demands more freedom from gender roles and today’s fashion industry responds by merging womenswear and menswear catwalks into one gender-neutral platform, prepare for the fashion pendulum to swing in unexpected directions. Men’s fashion has enjoyed so much variety in the past and while this new 21st century cultural shift might not spawn directly from the French flamboyance of 17th century Versailles or the dandyism of 18th century England, just remember, history has seen it before and likely, will again.