It was supposed to be a straight-forward renovation project for Paris-based architect Agathe Marimbert. Her clients were first-time buyers, a young couple who had recently moved into their second floor apartment of an 18th century building in the 10th arrondissement before deciding it could use an upgrade. Work was in full swing; Agathe’s plans for a remodelled, light-filled space were underway and builders were busy opening up walls when suddenly, things came to an unexpected halt. Something had been hiding behind the walls, and it wasn’t asbestos.

“During the restructuring of the apartment, we stumbled upon what appeared to be clandestine frescoes of French revolutionary supporters, which the previous owners had covered up during their installation of a bathroom,” Marimbert tells us. “It was by re-opening this enclosed space between what is now the kitchen and the living room (which we think used to be a double doorway) that we uncovered signs of something quite astonishing beneath the paint”.

Following the completion of the renovation, we sat down with rising Parisian architect Agathe Marimbert to find out more…

What exactly did you find on the frescoes?

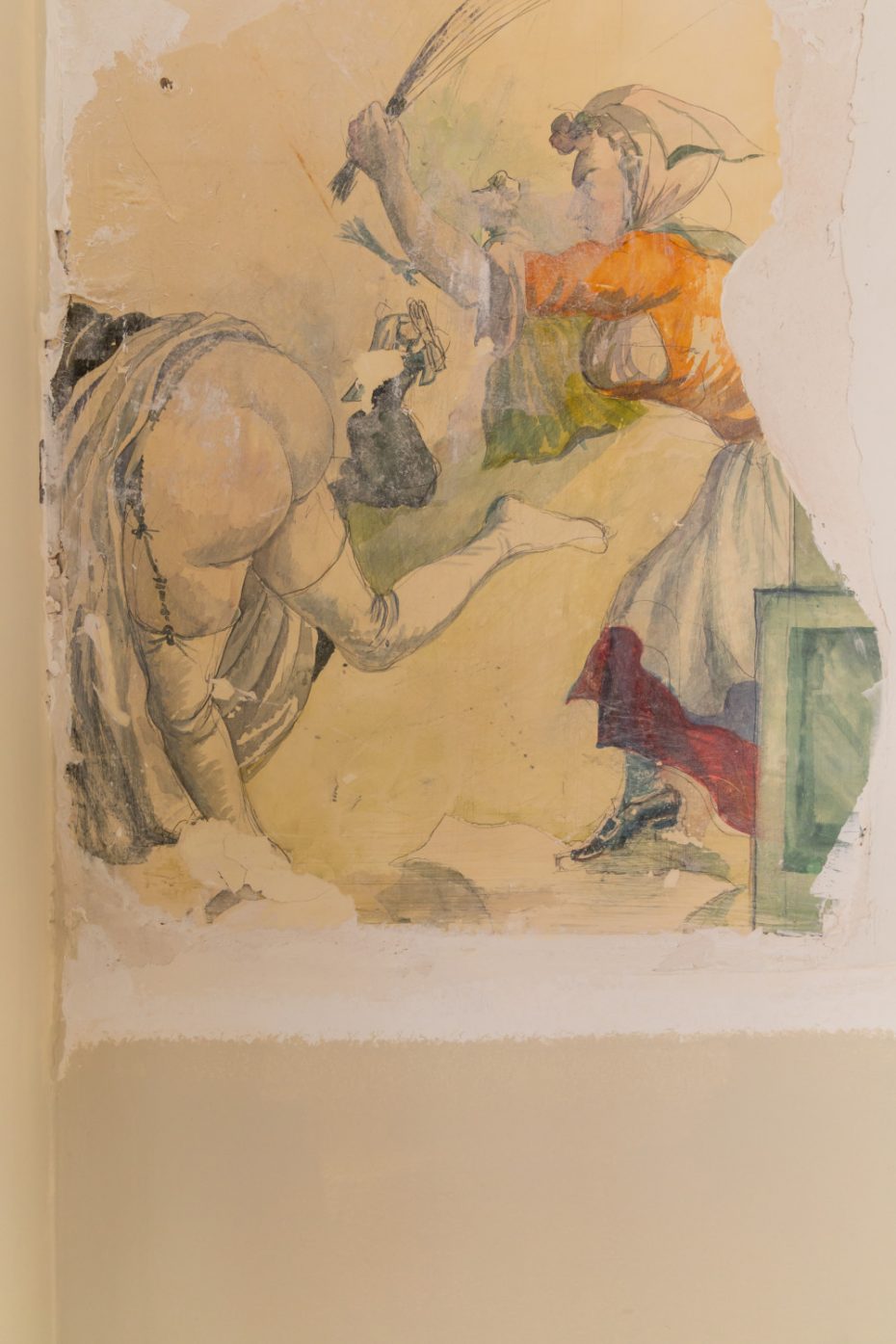

Agathe Marimbert: A large fresco adorns what is now the kitchen of the apartment, and depicts several scenes. On the left is the scene of a public caning or “bastonnade” as it’s known in French. In the foreground, a nobleman is being caned by a woman in a headscarf and apron. Another woman of the clergy, perhaps a nun (fitting with the anti-religious atmosphere of the revolution) is seen imploring the mercy of another woman, who is hitting her with reeds.

AM: Above that scene are other symbols more clearly linked to the time of the revolution: a bloody Guillotine, which has just performed its function. Part of the fresco has been lost, but we can imagine a head rolling into the basket.

We also found all the iconic symbols of the revolution. The banner and the cockade of France. We can read two inscriptions which translate to “unity, indivisibility of the republic, liberty equality, fraternity or death” and “we break with religious superstitions and place one’s faith in the supreme being and the rationality of enlightenment.”

AM: Other notable symbols of resistance we see are the Phrygian cap (which Marianne would wear later), the masonic eye (a reference to the Supreme Being), bayonets and pitchforks (reminding us that the lower classes fought with whatever was available to them). There are depictions of Roman civil servants known as lictors who were typically responsible for enforcing court decisions. Having also succeeded the monarchy, the Roman republic was a constant source of reference for the revolutionaries.

© Sloft

AM: A third scene depicts the assault on a manor by a troop attacking with a cannon. The attackers are encouraged by a violin player in the foreground, who we imagine might have lead them with a revolutionary anthem such as “La Carmagnole“.

Who is behind the works?

AM: The building dates to the 1780s, and according to records, used to be the commercial headquarters to a brotherhood of trunk makers. What is now my clients’ apartment on the second floor would have been the business’ office.

AM: Our trunk makers may very well be behind the frescoes. It’s commonly known that the vast majority of revolutionaries were provincial folks, artisans in particular, led by major players of a political movement known as the Club des Jacobins…

AM: We brought in an experienced restorer who has restored 18th century finds before but it’s been a struggle to fully identify and date the fresco without a signature. On a painting, typically we have more clues such as the frame, the canvas support etc. There is always the possibility that it had been added to over time before it was eventually covered up.

Does it often happen in Paris to find frescoes behind walls?

AM: This is the first time this has happened to me and I don’t know any professional peers that have encountered something like this in their work here in Paris. It’s amazing that the previous owner just painted over them, as if they made sure not to damage them too much while hiding them. In general, people either keep frescoes (especially those on the ceiling which are more frequent and recent) or destroy them completely by sanding them down. Unfortunately, our builders had already drilling into parts of the wall before the hidden frescoes became apparent, but as soon as they noticed traces of something beneath the layers, they called me over. Luckily, my clients happen to be very passionate about history. I can’t say many other customers would have chosen to keep these frescoes because they have quite a strong presence visually. Not everyone wants to have breakfast every day in front of a nun’s bare buttocks or a bloody guillotine.

Is there a protocol to follow when finding things like this?

AM: One should always bring in a specialist to get an opinion on what you’re discovering, but unfortunately, it’s rare that interiors are under protection, which all too often allows owners to ransack woodwork, painted decorations, and sculptural work. In our case, had previous owners left some kind of record of what was underneath the layers, who knows what else we might have found. The entire apartment might have been covered in 18th century graffiti. What we’ve sadly lost is lost forever, but we can recover and clean damaged elements and do it justice.

Do you think this increased the value of the apartment? Should we all start scratching behind our walls for treasure?!

AM: I think it certainly increases the value and cachet of the apartment. It’s always worth learning about the history of our buildings. Haussmann buildings may hold less surprises, but older buildings must surely still contain some nuggets waiting to be discovered.

Following this experience, do you hope to make similar discoveries in your career as an architect?

That would be great! Who doesn’t want to reveal what is hidden?! As an architect, finding clues to the original structure of the building is always fascinating. These kinds of discoveries anchor the project in a historical context and give it so much more meaning.