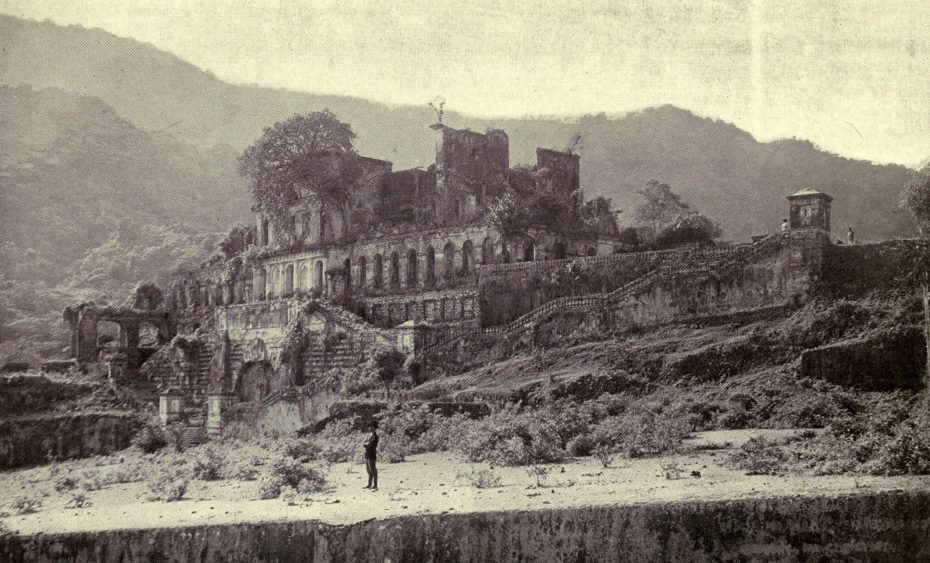

Once known as the ‘Versailles of the Caribbean’, its hollow ruins are one of the few lasting remnants of a forgotten royal court – the first Black monarchy established in the Western world that rose from the ashes of the Haitian Revolution. The brief reign of the first and only King of Haiti is both a surprising and troubling story, but no less worthy of our discovery, as we step back in time through the doors of this Caribbean palace to a lost world, confronting the eye-opening history of the first nation on earth to officially abolish slavery.

French and British abolitionists get much of the credit for the destruction of the transatlantic slave trade according to history, but it escapes many that the date marking the beginning of the Haitian Revolution is designated as the International Day for Remembrance of the Slave Trade & Abolition. Haiti’s independence from French colonial rule remains the only instance in world history of a successful slave rebellion – and the founding event of the first modern Black republic.

Here are the key players to know: founding fathers Jean-Jacques Dessalines (who became Emperor Jacques I), Alexandre Pétion (who became President) and General Henry Christophe, (who later became King Henry I). Like all burgeoning nations throughout history, there was a power struggle between the three, and within just a few years of independence, Haiti’s new Emperor, Jacques I, had been assassinated by his own generals. His death led to the country’s temporary partition, with Henry declaring himself King the north and Pétion, leader of the south. And with that, the building of King Henry I’s Haitian Kingdom in the north began…

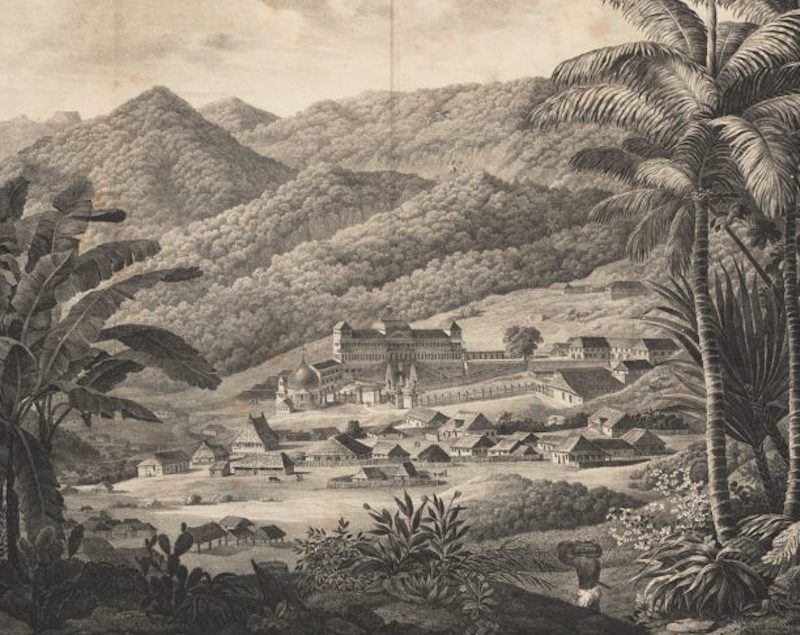

Six richly adorned châteaux, a massive citadel and eight beautiful palaces were constructed to rival the most opulent structures in old Europe during his short reign between 1811 and 1820. Haiti’s “Sans-Souci Palace”, meaning ‘Carefree’ – was the largest of the palaces commissioned. Its gardens were immense, complete with artificial springs and a system of waterworks. Inside, there was said to be mahogany floors throughout, flowing silk curtains and at the top of the grand staircase, a fountain with a gilded sun inscribed with the motto “Je vois tout, et tout voit par moi dans l’univers” (I see everything, and everything in the universe is seen by me”).

The new King of Haiti, known to his former revolutionaries as Henri Christophe, implemented an entire system of nobility with hundreds of dukes, counts and barons who arrived at court in gilded carriages dressed in lavish attire to attend opulent feasts, dances and operas. It was indeed all very reminiscent of the French “Sun King” and his pre-revolutionary Versailles, and was often compared as such by foreign visitors. But this was all part of Henri Chistophe’s plan to show the capability of the Black race to Europeans and colonial powers.

Foreign artists, scientists, musicians and mathematicians were invited to the grand palace, but historical documents have revealed visiting dignitaries frequently mocked the King and his court behind closed doors. Some of the official nobles in his majesty’s royal circle had been given titles such as the Duc de Limonade and Duc de Marmelade, which British dignitaries found comical, unaware that the names were actually derived from place names given by the previous French colonists.

Nevertheless, King Henri was a hero to British abolitionists. He stood up to colonial powers, seized their slaving vessels and liberated their captives, welcoming enslaved survivors as free Haitian compatriots. He brought national education for Haitian boys and girls by sponsoring foreign teachers in his kingdom. He urged Haitians to cultivate wheat and other grains in order to become less dependent on foreign imports. He also created a programme whereby any Haitian could apply to acquire the farms of the former French planters.

Following Haiti’s independence however, both France and the United States pursued a policy that prevented the lucrative ex-colony from participating in trade in the Atlantic. Isolation on the international stage made Haiti desperate for economic relief. Not to mention, the King had a few massive building projects to pay for. On paper, Henri’s plan for a new tax-free society under labour laws called the Code Henry, were praised by philosophers, but in reality, they more closely resembled feudal policies of forced labor.

His critics would argue that as Haiti’s first monarch, King Henry had merely brought old-world despotism to the island and questioned whether any of his policies benefited the average Haitian citizen. Accused of effectively re-enslaving the Haitian people and fearful of an imminent coup or assassination, he shot himself with a silver bullet at the age of 53. His son and heir was assassinated 10 days later. Henry’s queen, Marie Louise Coidavid and their two daughters sought refuge in England where they were taken in by abolitionist Thomas Clarkson.

What happened after the fall of the first Black monarchy in the Western world is perhaps the most shocking part of this little-known history. Within a few years, as had been feared by Haitians ever since their independence, France sailed to the Caribbean island with warships in 1825, demanding Haiti to compensate France for its loss of slaves and its slave colony.

In exchange for peace and French recognition of Haiti as a sovereign republic, France demanded the modern equivalent of $21 billion dollars as a so-called “independence debt” which took Haiti 122 years to pay off (the final payment was made in 1947 via what is now Citibank). In addition to the payment, for many years France required that Haiti provide a 50% discount on its exported goods to them, making repayment even more difficult. It is recognised as one of the main factors that has caused the country’s persistent poverty. This “debt”, which Haiti desperately needed to create institutions for education, industry, and commerce, has never been remedied and likely never will.

As one journalist puts it: “France’s demand for reparations from Haiti seems comically outrageous today – equivalent to a kidnapper suing his escaped hostage for the cost of fixing a window that had been broken during the escape”.

Haiti was the richest and most productive European colony in the world going into the 1800s and France’s historic wealth was practically built on its sugar trade. As for Henri Christophe’s Haitian “Versailles”, it was reduced to rubble in an earthquake in 1843. Its ruins are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.