Not-so-fun fact: Until January 31st of 2013, it was illegal for women in France to wear trousers. It made headlines at the time when a 200 year-old law requiring women to ask police for special permission to “dress as men” or else risk being taken into custody, was finally revoked. The law had been kept in place since 1799, despite repeated attempts to repeal it, in part because officials said the unenforced rule was not a priority, and part of French “legal archaeology.” In a nutshell, lawmakers simply forgot the law still existed on the books. While comically absurd, this is a poignant reminder of the many liberties we take for granted today in Western society. While modern freedoms offer women a variety of sartorial choices, we forget that something so simple as the right to wear trousers was one of the most debated subjects of the women’s rights movement. Let’s step into the trousers of the women who have paved the way for us…

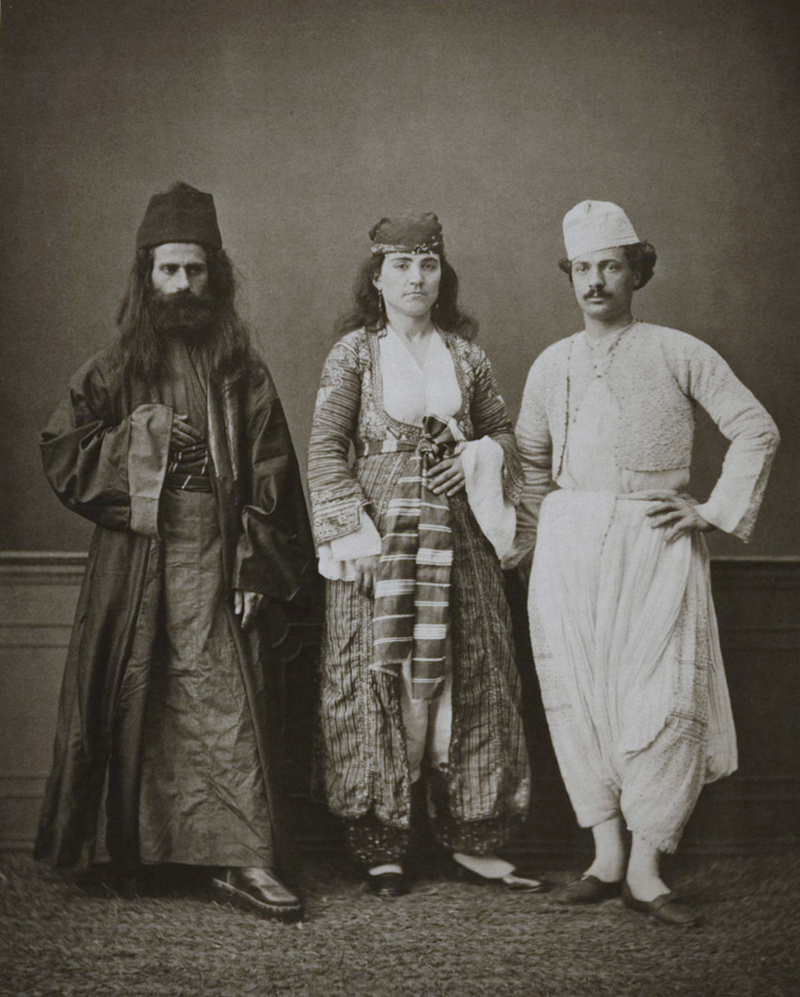

While Western women were subjected to a trouser ban for much of history, many societies in Eastern cultures did not share the same sentiment. Researchers estimate that Central Asian women have worn trousers for thousands of years, and women in pantaloons were widely documented by Western visitors to the Ottoman Empire. So why is it then that these two societies shared vastly different views regarding women in trousers?

There’s an assumption that women’s desire to wear pants came from their desire to appear less feminine in their quest for gender equality. In truth, western women’s taste for trousers didn’t originally stem from a desire to imitate men, but rather, from Ottoman Muslim women who had been wearing trousers for centuries.

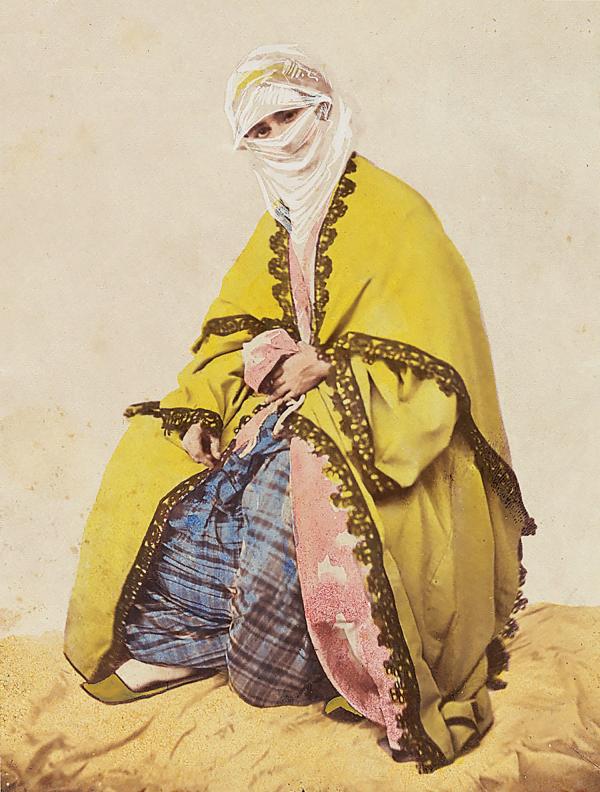

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu is one of history’s rare examples of women who had the privilege of travelling abroad during the age of Enlightenment. In 1716, she traveled to Constantinople with her British ambassador husband, and found herself enamoured with the Turkish style of dress. As one of the first Europeans to document daily life in the Ottoman Empire, during her trip, she observed that women appeared to be freer than Western women as a whole. They could walk unaccompanied at night, obtain a divorce, and even wear trousers in the streets.

Unlike Western society, women’s trousers were not a matter of fashion but practicality. In ancient Turkish culture, men and women’s clothing was almost identical in appearance. Both genders were accustomed to horseback riding for long distances and “unisex” Turkish clothing showed a societal preference for practicality and comfort over gender norms.

Typical Turkish trousers were called şalvar, described as long and baggy, falling past and gathering tightly at the ankles. They more closely resembled the modern trouser long before European men had adopted anything similar (they were still stuck in their short breeches and calf-enhancing hosiery until the late 18th century).

Lady Mary returned from her trip with trunks of clothing worn by the Muslim women she encountered, sharing them with members of her social circle, even posing for public portraits modelling the garments.

She wrote about her experiences and observations, creating intrigue amongst the fashionable elite. Her letters and firsthand accounts invoked honest conversations about freedom of dress, property rights, and other social, economic, legal, and marital freedoms that women were denied in Europe. As more women began to travel and discovering foreign cultures, it seemed Western society, which held a strong Eurocentric bias, was falling behind the East regarding women’s rights issues.

So in a surprising historical twist, it was fact Muslim women who we can thank for greatly influencing many upper-class educated western women in matters of style and social reform.

Despite full-length skirts being the norm for Western women, the “Dress Reform Movement” picked up traction in Europe and the Americas during the Victorian era. In this period, women were openly advocating for their rights to wear trousers. One popular concept that emerged was the “rational dress” argument, which asserted that trousers should be allowed because of their practical and comfortable features. After all, trousers permitted a woman to move around more easily and protected her legs from the cold.

Rational dress enthusiasts were also staunch proponents of the radical women’s rights movement. They viewed society’s rejection of trousers as another symbol of women’s oppression. Amelia Jenks Bloomer, the first woman to own, operate and edit a newspaper for women, is a notable example. She controversially adopted a version of women’s trousers as worn by women in the Middle East and Central Asia, topped by a short dress or skirt and vest, while promoting it in her magazine.

As more women emulated the style, including prominent American women’s rights leaders like Elizabeth Stanton, it was soon dubbed as the The Bloomer Costume or “Bloomers“.

But for the majority of Victorian society, which valued modesty and femininity, the women’s trouser held no place. For Christian particularly, skirts and dresses were the only appropriate lower garments for women and anything else fell into the dominion of men. Additionally, the adoption of Turkish culture was viewed by many to be heathen and un-Christian. The fact the bloomers allowed women to take part in more activities such as horseback riding and other forms of exercise also attracted backlash from the medical community, which argued that wearing trousers was a danger to women’s fertility. Bloomer-wearing women were thus depicted as impious, morally-depraved infertile heathens!

The criticism, harassment and humiliation endured by women in bloomers eventually proved too much. Even Amelia Bloomer herself had dropped the fashion by 1859, in favour of the newly-invented crinoline, which she considered as a “sufficient reform”. The new hoop skirts were much lighter and “easier” to manage and women quickly forgot the Turkish dress alternative. Activists feared that the attention on women’s trousers detracted from other more pressing issues in the women’s movement debates. Once again, they began dressing more “lady-like” to secure crucial ballots such as the women’s right to vote.

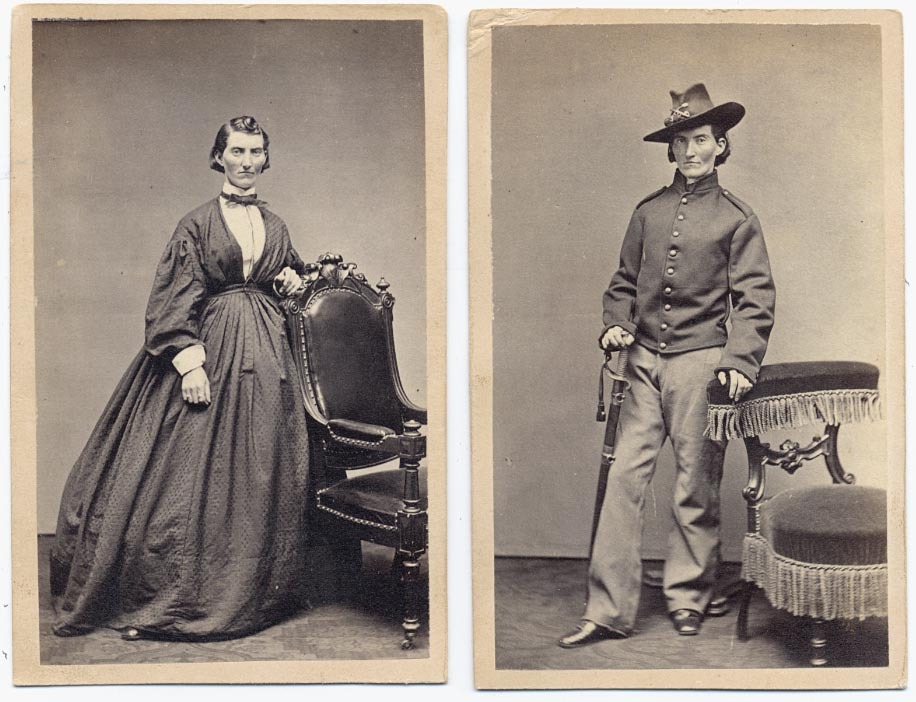

This is not to say that women never wore trousers again in the 19th century. During the American Civil War as well as European wars, some women donned trousers while acting as field nurses. And let’s not forget the women warriors who served wine on the battlefield and the gender fluid “secret soldiers” of the American Civil War. Some of the more daring and ambitious women also realised they could get paid more for work or gain access to certain professions if they disguised themselves as men.

By the early 20th century, the attitude surrounding women in trousers began to expand, along with the scope of women’s activities, such as women’s tennis and bike riding becoming the norm. Once again, women altered their clothing to achieve their desires, but still, wearing trousers was only acceptable for athletic purposes and they did not have the right to wear trousers in public. In 1938 American teacher Helen Hulick was jailed for five days after denying three judge requests to show up to court wearing pants. Pictured below is Marlene Dietrich, arriving at a train station in Paris in 1933. for violating the ban on women wearing trousers. The internet often captions this as Marlene “being detained by police for wearing trousers in public during her arrival in Paris in 1933”. While her look did send the French press into a frenzy of commentary on her “gender-bending” ways, there was no warrant issued for her arrest, although no doubt some newspapers would have picked up on the French law at the time which prohibited women from wearing trousers.

It was trend-setting style icons like Dietrich, Coco Chanel and Katharine Hepburn that helped bring trousers or slacks into the mainstream western clothing market during the 1930s however.

One Vogue excerpt reads:

“…if people accuse you of aping men, take no notice. Our new slacks are irreproachably masculine in their tailoring, but women have made them entirely their own by the colours in which they order them, and the accessories they add.” She suggested that the fashionable, modern woman should wear slacks “practically the whole time” – unless she was the guest of “an Edwardian relic with reactionary views.”

In the 1940s, World War II further encouraged women to bring trousers into their everyday wardrobe as they played a vital role in the war effort. Taking a step back in the 1950s however, post-war values advocated that women leave the workforce and take up child-rearing once again, shifting women’s trends back to dresses and skirts. During the second wave of feminism in the 1960s and ‘70s, women’s trousers finally gained acceptability in the workplace and several state laws in America declared it unlawful for employers to deny workers the right to wear pants based on their sex. We saw the rise of the pantsuit or “trouser suit” in the 80s and 90s, when American women holding political office could finally gain the right to wear trousers in their local and government Senate. Today, us ladies don’t give much thought to slipping into a pair of vintage jeans, leggings, or trendy corduroys before leaving the house. It’s easy to forget women’s long and turbulent struggle to advocate for something so basic as the right to wear trousers. At least now that you’ve read up on this not-so-straightforward story, you can call yourself a real smarty-pants!