During the pandemic, the Eiffel Tower has been undergoing a fresh paint job ahead of the 2024 Olympics that harkens back to its golden hue of the early 20th century. But at that time, the Eiffel Tower was more than just an attraction: Gustave Eiffel was using his new tower as his personal laboratory of scientific innovation. In 1909, Eiffel built its first wind tunnel at the foot of the tower, which was made available to the earliest pioneers in aviation and aircraft design. The wind tunnel, still in service in Paris, inside “the oldest aeronautical test laboratory still in working order,” can be considered one of Eiffel’s littlest-known monuments.

While best remembered as the architect behind the Eiffel Tower and the internal structure of the Statue of Liberty, Gustave Eiffel was a civil engineer by training with an entrepreneurial spirit. Eiffel made a name for himself at the young age of 26 as the overseer behind the Bordeaux railway bridge, known as the Passerelle Eiffel. He constructed the Eiffel Tower between 1887 and 1889 to be the centerpiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle. At the inauguratiaon of what was then the tallest structure in the world, he said, “I ought to be jealous of the tower. She is more famous than I am.”

Although, the tower was supposed to only stay up for 20 years and many artists and writers publicly shared their dislike of its architectural aesthetic. Eiffel realized to save his tower, he would have to make it more than just a cultural landmark. “It will be for everyone an observatory and a laboratory,” he said, “the likes of which has never before been available to science.” He solidified this commitment by engraving the names of 72 men in science into the first-floor edge.

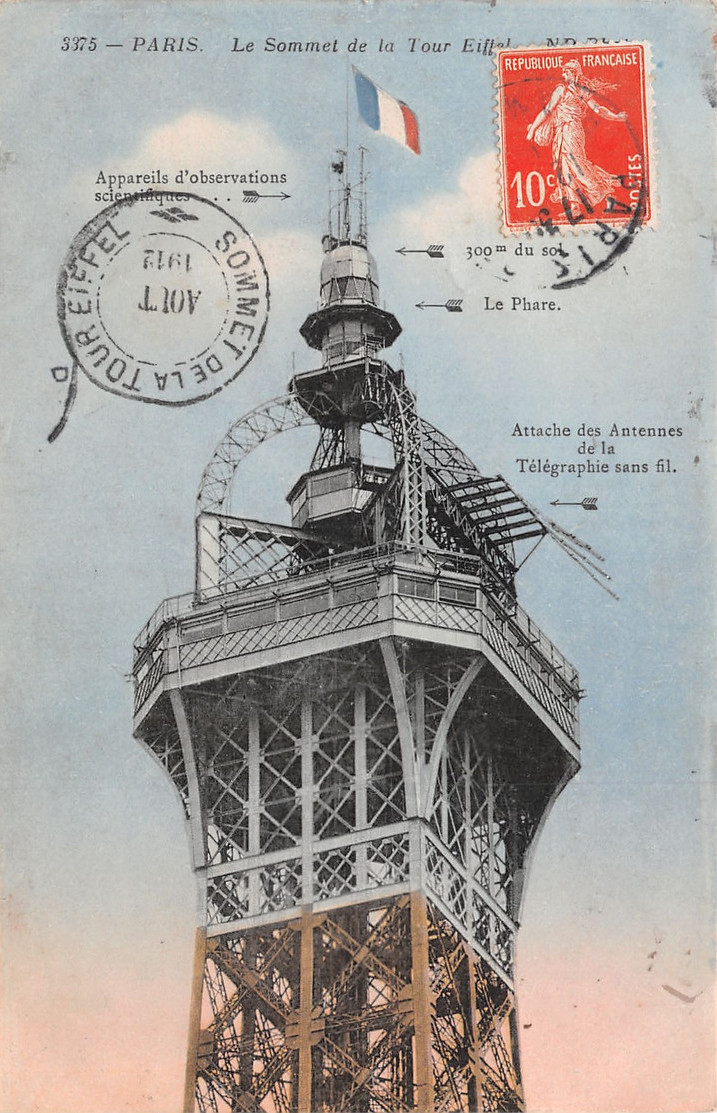

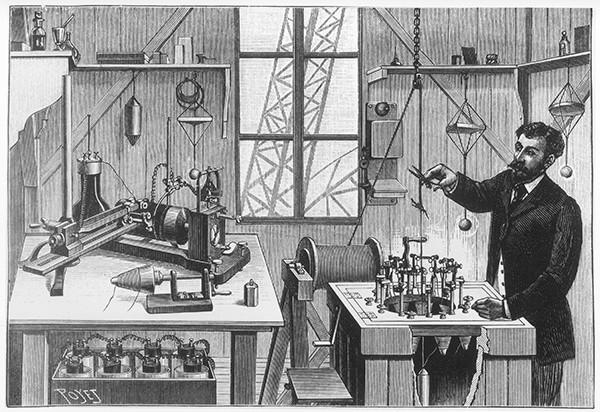

A weather station was installed at the top as well as a manometer, which measures the pressure of gases and liquids. Eiffel had inventor Eugène Ducretet to conduct experiments, including sending a wireless transmission from the tower’s third floor to the Pantheon, 4 kilometers away. Eiffel even let the French military research radio communication. This proved a valuable asset during World War I, when French forces jammed German communications, a significant factor in the winning the First Battle of the Marne. An intercepted message between Germany and Spain also led to the arrest of exotic dancer and spy Mata Hari.

Following his involvement as an engineer in the Panama Scandal, a corruption case involving a French company that failed to build the famous waterway, Eiffel switched focuses. He knew that rigorous scientific testing of how objects moved through air would be needed in the budding aviation industry. Starting in 1903, when the Wright brothers also had their first powered flights, Eiffel experimented with drop tests. He measured the impact of gravity on two- and three-dimensional shapes released down a 115-meter cable on the Eiffel Tower.

He designed a machine to record drag and made observations about the relationship between surface area and resistance, which allowed him to found the fundamental laws of air resistance. The bottom of the Eiffel Tower wasn’t the only space for research. His third-floor office was a hotspot for studying astronomy and physiology and a large-scale Foucault’s Pendulum was connected to the second floor’s underside.

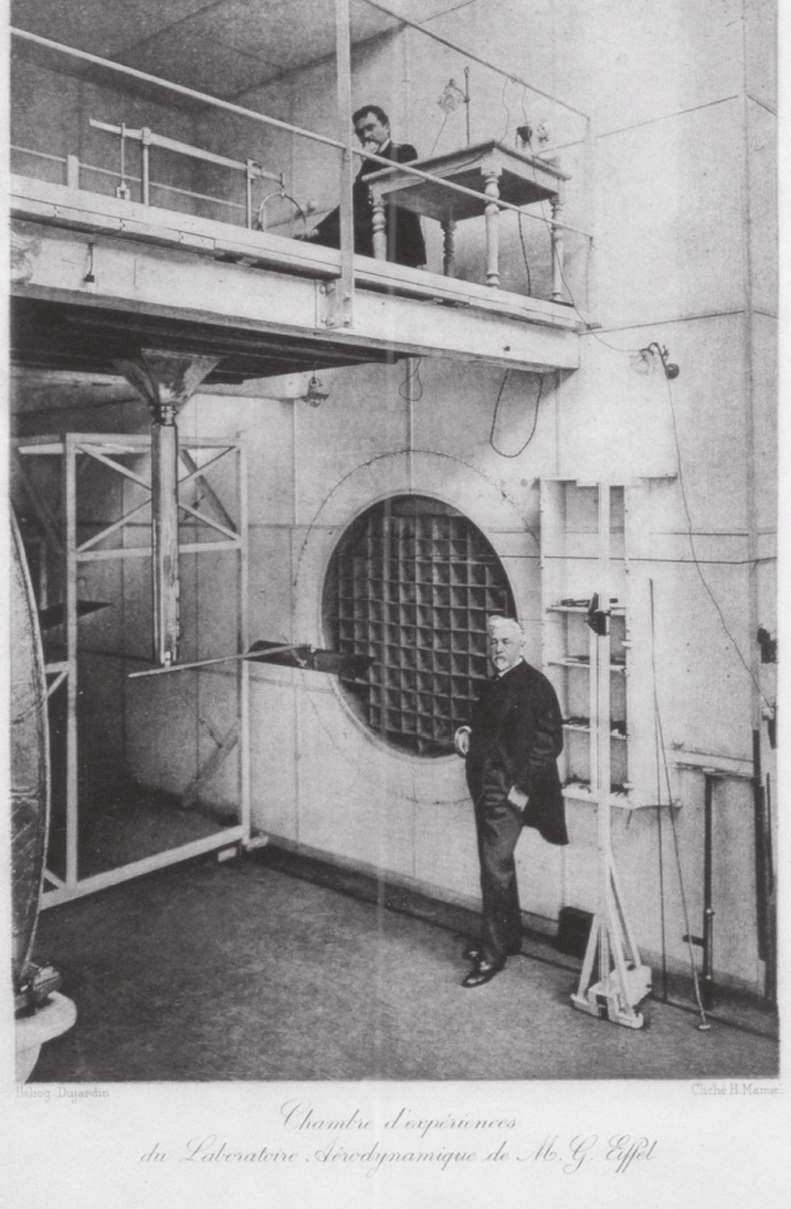

Although, Eiffel realized he needed a more sophisticated apparatus to study relative motion. By the time he were in his 70s, his status and wealth was such that he decided to build one of the world’s first wind tunnels. He had long been fascinated by wind, even worrying it would knock down his tower. As he said, “The wind has always been a concern for me. It was an enemy.”

Wind resistance not only tests an object’s durability and strength, but also its aerodynamic potential. Powered by the same generator that supplied electricity to the tower’s elevators and lights, a Sirocco blower created a horizonal air column that was 1.5-meter in diameter. With an airspeed of about 20 meters per second, the tunnel was meant to confirm “the theory that air moving around a stationary body produces the same drag as the body moving through still air.”

From 1909-1912, Eiffel conducted around 4,000 tests with his so-called “Eiffel Tunnel,” including research on more than 20 planes. Wilbur Wright’s 1908 trip to France, in which he gathered crowds for his flights and appearances, further intensified aviation mania.

Having proved the potential of the technology, Eiffel decided to expand. In 1912, he moved his tunnel to the 16th arrondissement and added a second, larger wind tunnel to his laboratory. With increased space, he continued to test scale models of aircraft design, which was especially important with World War I looming.

In this vintage reportage from 1962, Eiffel’s grandson takes us into the lab…

One plane brought to the lab was the Paulhan-Tatin Aero Torpedo, a collaboration between pilot Louis Paulhan and airplane pioneer Victor Tatin. The experimental torpedo had been designed to eliminate drag and was displayed at the Grand Palais in Paris. Peugeot also tested a car in the wind tunnel in 1914, changing the back design to be more aerodynamic.

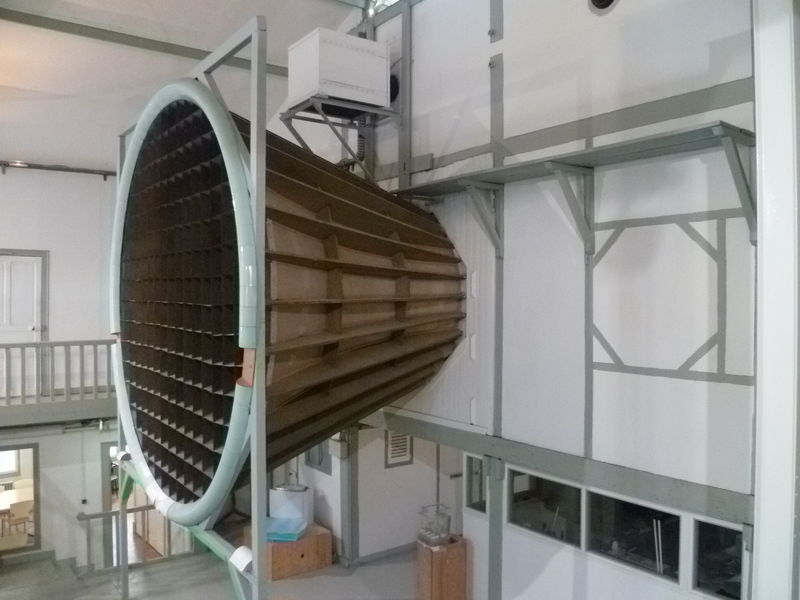

The tunnel was donated to the French government in 1920 and Eiffel died in 1923 at age 91. In 1929, the Groupement des industries françaises aéronautiques et spatiales (GIFAS) became in charge of the lab. By 1945, the construction and automotive industries, especially for racing cars, began using the facility more frequently. Porsche relied on the tunnel while designing its 917 Le Mans car as well as Audi, Citroen and Ligier. The Eiffel Tower itself continued to be a conduit for communications innovation, such as broadcasting audio programs (Radio Tour Eiffel) and television, including the Queen of England’s 1953 coronation.

In 1983, the wind tunnel was classified as a historical landmark. And even today, one of the two tunnels is still functional, making it “the oldest aeronautical test laboratory still in working order.” The two-meter fan produces a wind at the speed of 100 km/h. In 2001, the wind tunnel was transferred from GIFAS to the Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment, which tests boats, bridges, cars and stadiums as well as continued innovations in plane design. This has significant ramifications for sustainability, as vehicles that are more aerodynamic often burn less fuel. In this setting, more than 100-year-old technology and the designs of tomorrow meet.

As Benoit Blanchard, manager of the Laboratoire Aerodynamique Eiffel, told aeronewstv.com in 2015, “He [Eiffel] made a wind tunnel that, even today, is still modern enough to be interesting and competitive in many areas concerned with aerodynamics.”

Aeronautical engineering students still visit the lab to study the construction of tomorrow’s aircraft. Under normal circumstances, the facility is open for special visits (enquiries: +331 42 88 47 40).