You would think that being Frank Lloyd Wright’s earliest protégé; the woman behind so many of most of the iconic drawings to come out of his practice; might just give you a leg up in the world. So how is it that the legacy of one of the first women to become a licensed architect in the world can so easily be erased from history, her story condensed down into a mere footnote, clumsily attached to the work of her male partners? The work of Marion Mahony Griffin is still present across America and Australia, but the woman behind the architecture has been given little of the attention that she deserves.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation/Frank Lloyd Wright Trust

Marion Mahony Griffin was born in Chicago in 1871, the same year that the Great Fire destroyed over 3 square miles of the city, killing hundreds. Whilst Marion would have been all but eight months old at the time, The Great Rebuilding as it was known, would go on to influence her in later life, inspired by two of the major architects who took in the project, Daniel Burnham and Louis Sullivan.

Perhaps it wasn’t all too surprising then that Marion was destined to make waves, having grown up with a mother who strove to evoke change, particularly for women. After Marion’s father Jeremiah died when Marion was 11, her mother Clara trained to become a teacher, establishing herself as a respected school principal. Clara was also part of the pioneering Chicago Woman’s Club, a group who campaigned relentlessly for women’s rights.

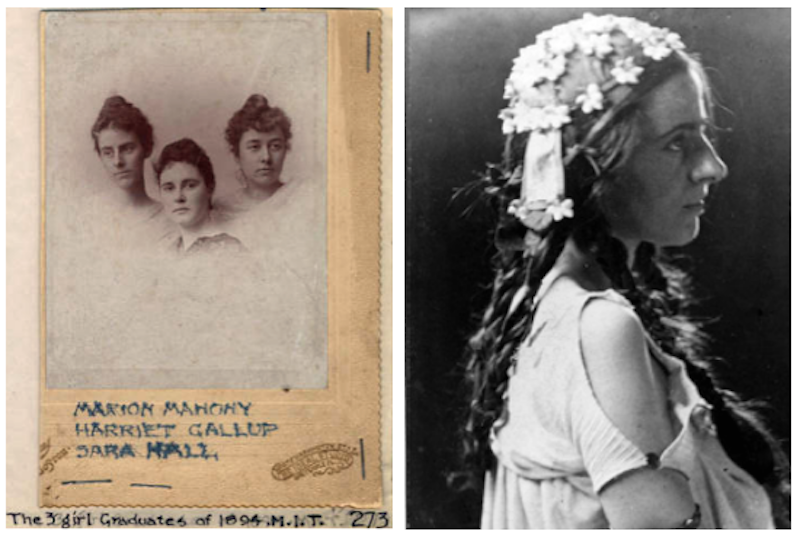

Marion’s formative years and her mother’s influence may well have set the tone for Marion’s own ambitions, which gave her the confidence to apply to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to study architecture. Here she became only the second woman to graduate with such a degree. The first, Sophia Hayden would give up the idea of a career in architecture, out of sheer frustration for her treatment in the professional community.

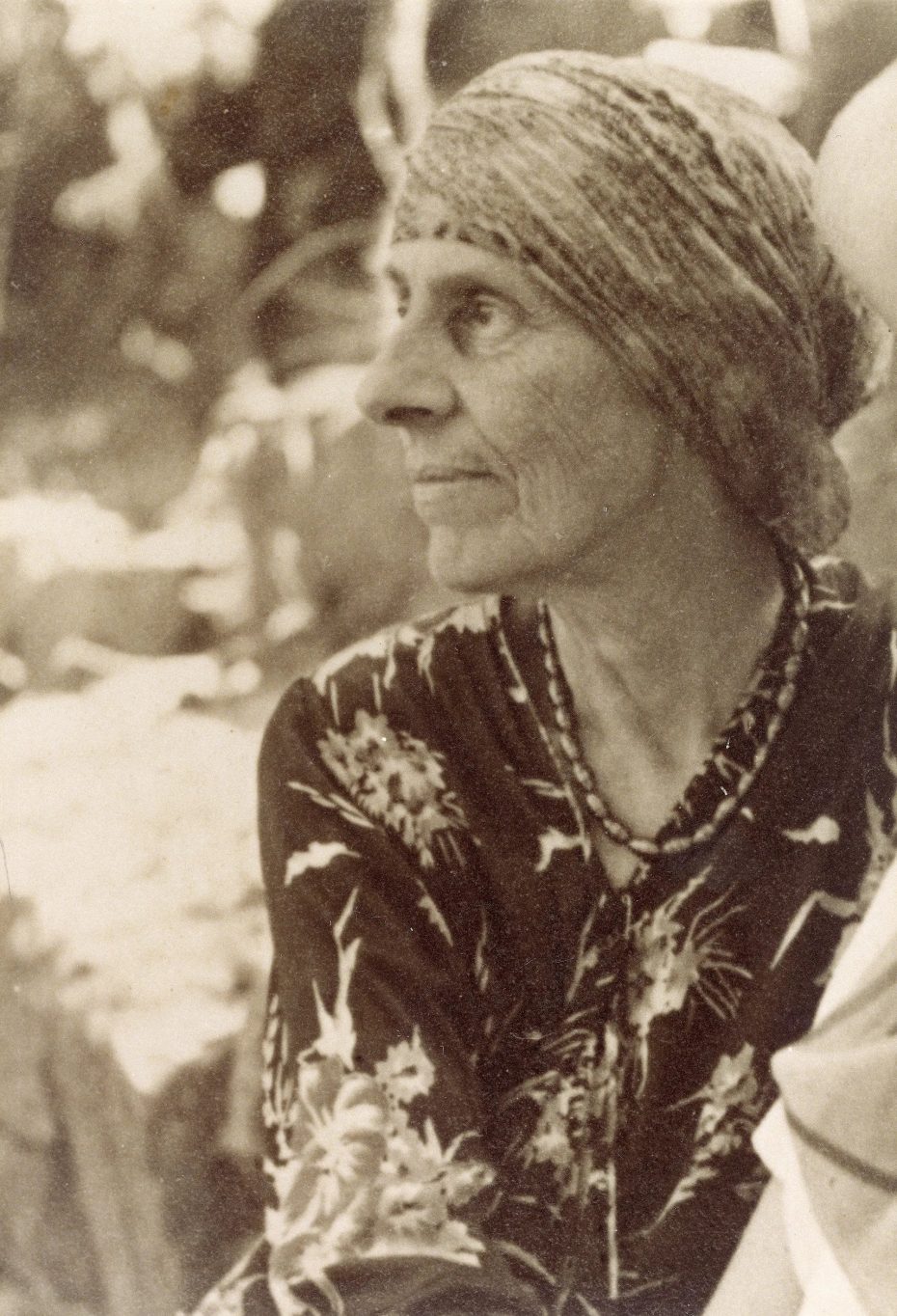

Marion however, was undeterred, perhaps thanks to what colleagues and acquaintances described as a “pronounced personality” and her ability to get a room full of men to stop and pay attention to her.

After graduating from MIT, Marion took herself off to Europe, travelling across the continent and undoubtedly making mental notes of the landscapes and environments which would later be interwoven into her work. When she hopped off the boat after her trip and presented herself at immigration, she declared herself; Marion Mahoney, architect.

Enter, Frank Lloyd Wright, renowned architect, who to this day often gets described as one of the greatest pioneers of the 20th century, and credited for realising the first truly American architecture. Unfortunately for Marion, despite being Lloyd Wright’s very first employee and working with him for 15 years, she gets little recognition for her work alongside him. Marion’s colleague Barry Byrne would later say of Marion that, “when around Wright there was a real sparkle.”

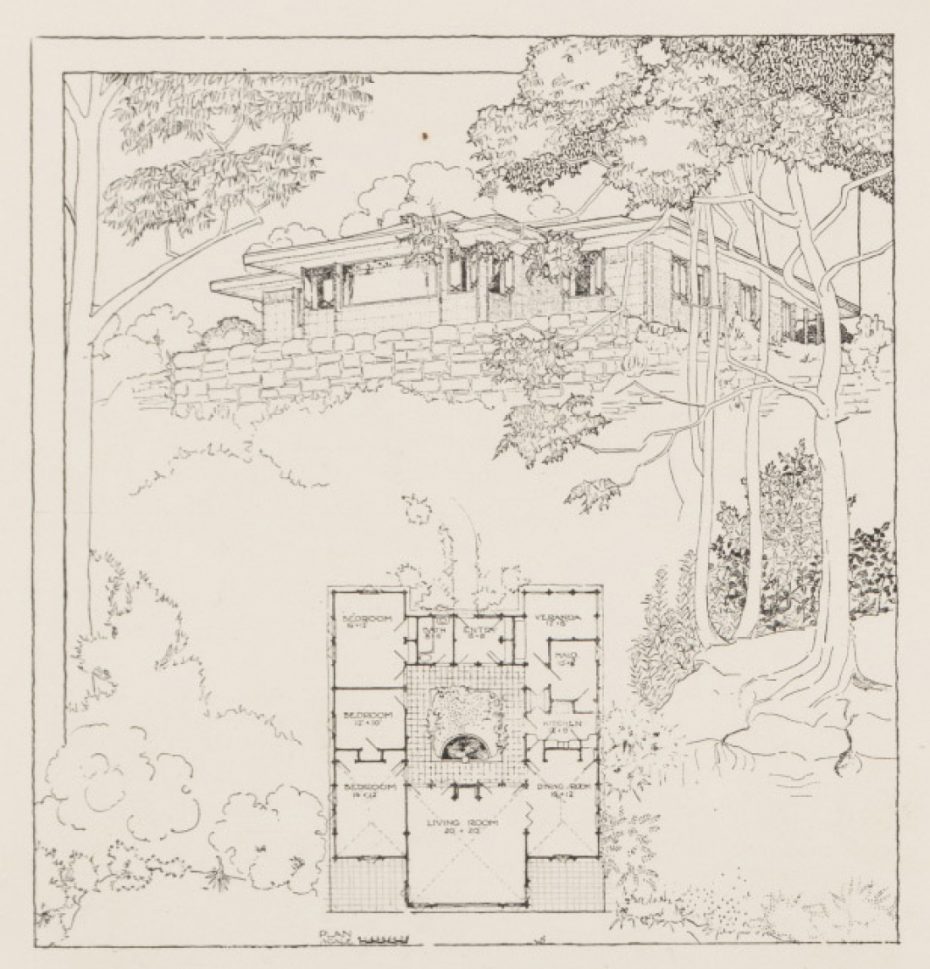

During her time working for Lloyd Wright, Marion would often win a kind of informal competition that Lloyd Wright would host in the office, pitting his protégés against one another in a bid to design parts of a project for him. Marion would more than often come out of these competitions triumphant, but unacknowledged. For if people were to later reference these elements as being designed by Marion, they would be abruptly set straight by Lloyd Wright.

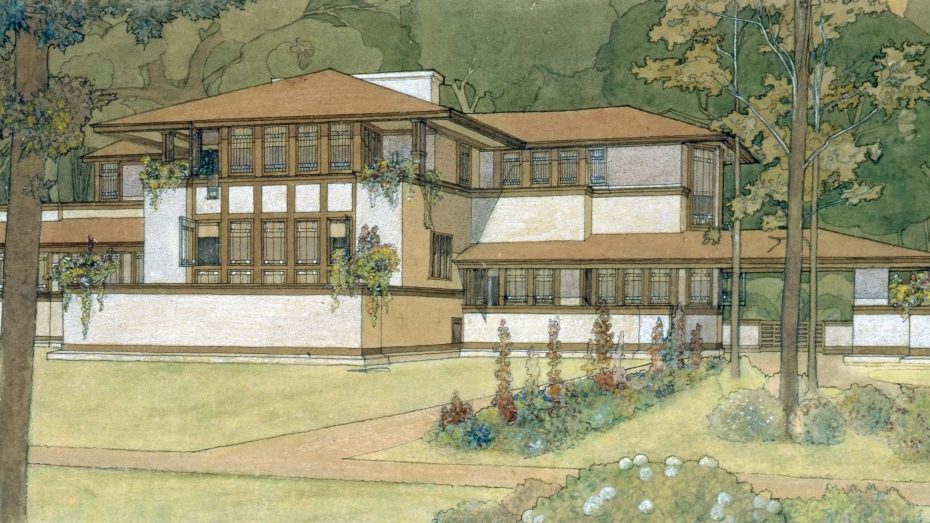

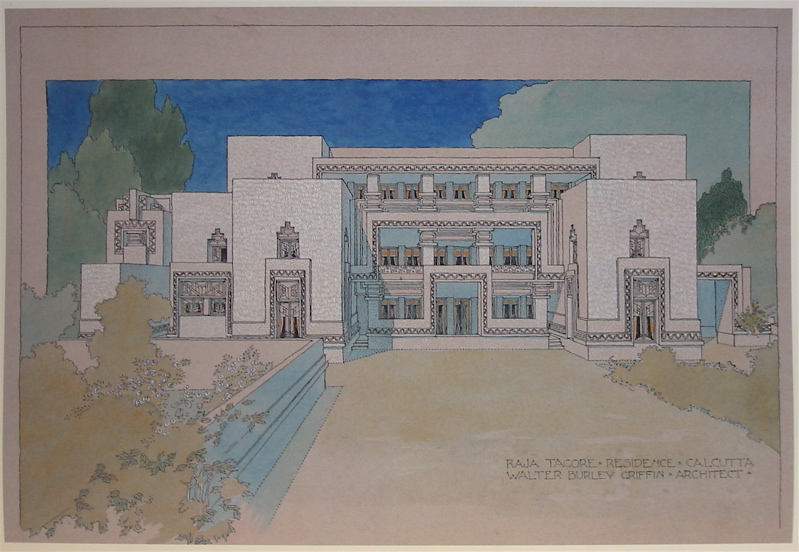

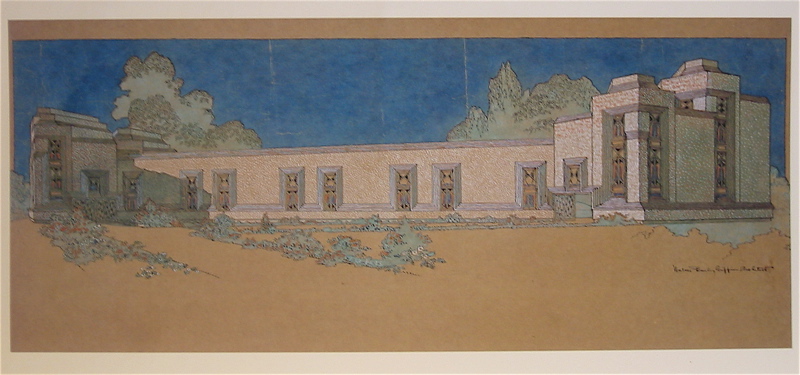

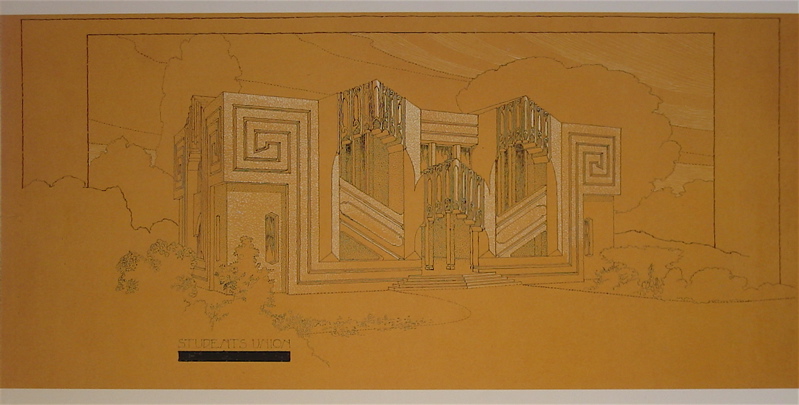

Indeed, some of Marion’s best work was long attributed to Lloyd Wright. In the German publication Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe, a much-celebrated collection of Lloyd Frank’s lithographs, current historians now credit Marion with at least half of the drawings. Marion is consistently still praised for her architectural renderings completed during her time with Lloyd Wright, which a number of architectural historians have cited as being among the finest ever produced.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the relationship between Marion and Lloyd Frank was to turn sour. In 1909, Lloyd Wright left for Europe with a new woman on his arm, leaving both his practise and his first wife behind in America. Marion was devastated that Lloyd Wright could abandon his work so easily, later writing in her unpublished memoir, The Magic of America, that, “when the absent architect didn’t bother to answer anything that was sent over to him, the relations were broken.”

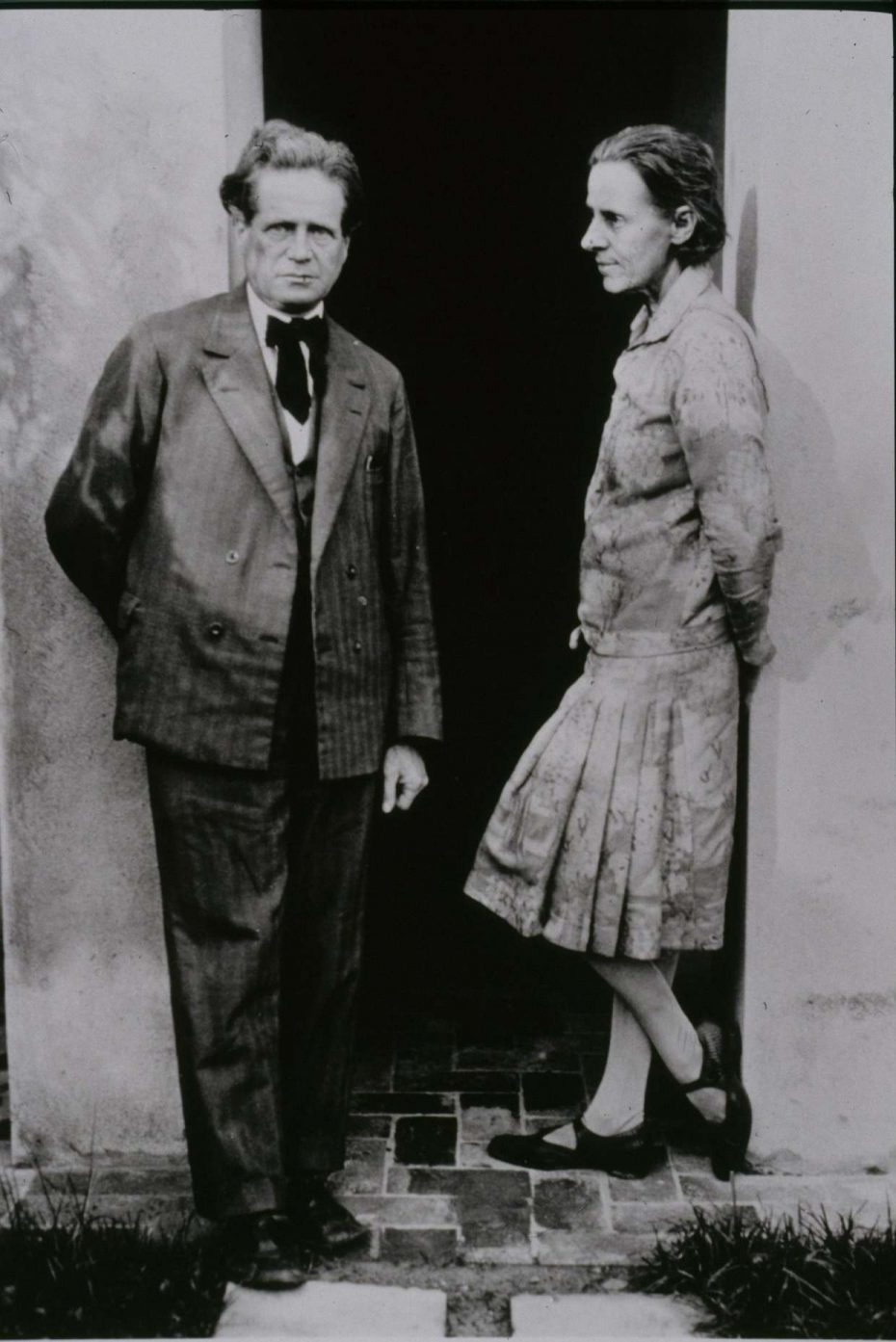

Two years later Marion went on to marry fellow architect Walter Burley Griffin, whom she had met whilst working for Lloyd Wright. A sign of the times, Marion seemed content to once again work in the shadow of another male architect, citing that she was happy to be his “useful slave”. The pair established a successful architectural firm together and began to take on projects across America.

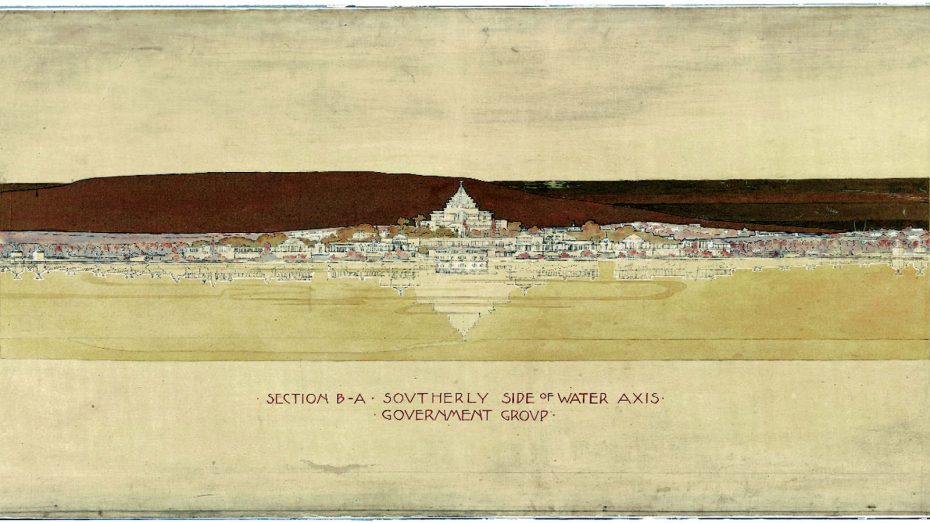

In 1912, Marion persuaded Walter to enter a new competition, which sought to find architects to design the new capital of Australia, in Canberra. In typical Marion style, it was her exquisite renderings which took in the richness of the Australian landscape, that won the competition for the couple.

As was the theme of Marion’s career, her crucial input to the project went largely unrecognised in the media, with most newspapers heralding the work of Walter and all but erasing Marion from the picture. It was only thanks to a studio visit from the Australian author (Ms.) Miles Franklin and Alice Henry, a feminist activist from Australia, that the Sydney Daily Telegraph referenced Marion’s involvement in the project.

With the media buzz around the Griffins and their acclaimed win to design the capital of Australia, news soon reached Lloyd Wright. It’s safe to say that Marion’s former boss was less than supportive of his ex-prodigy, in fact he made it publicly known that he considered the Griffin’s work “second-rate”.

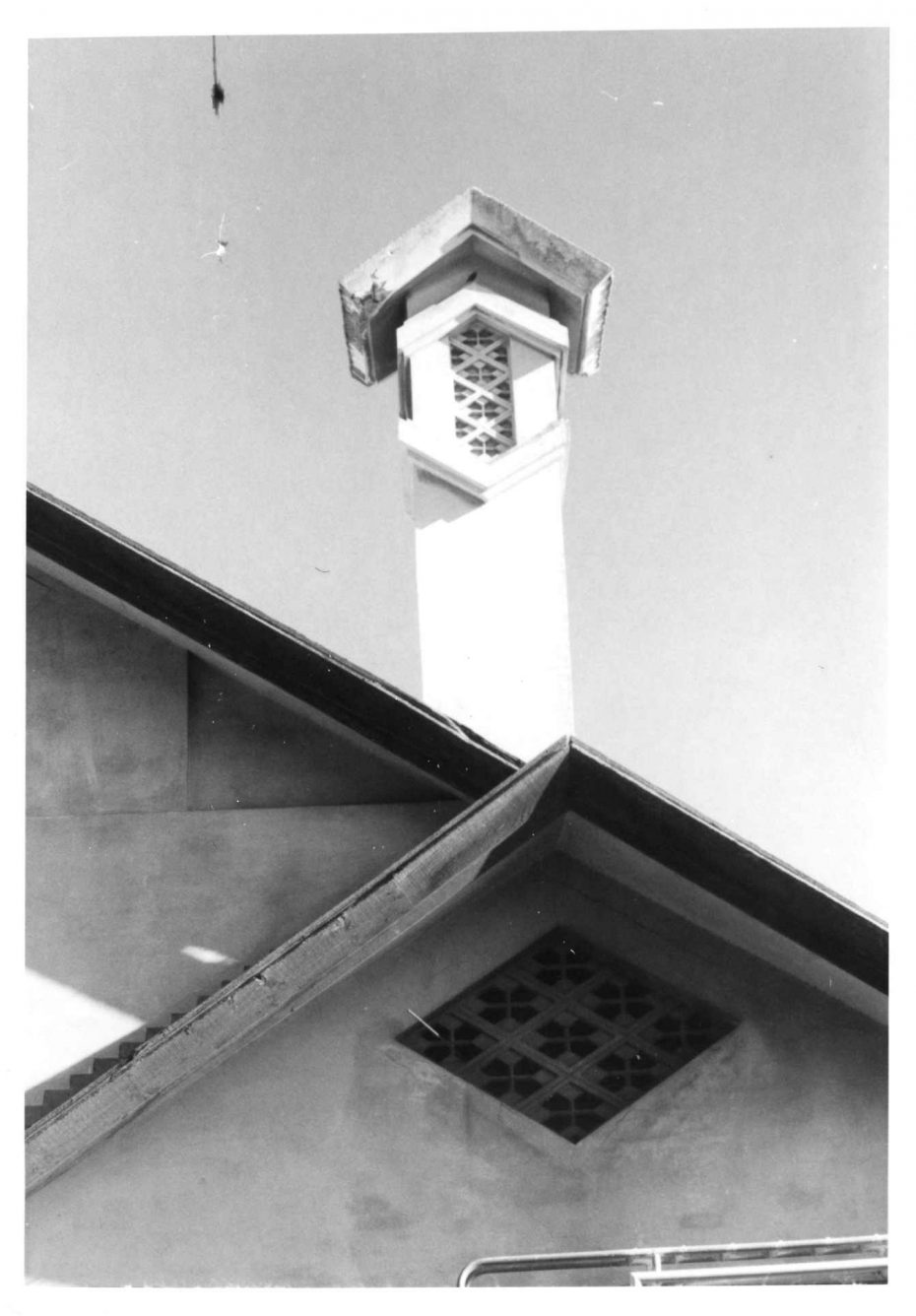

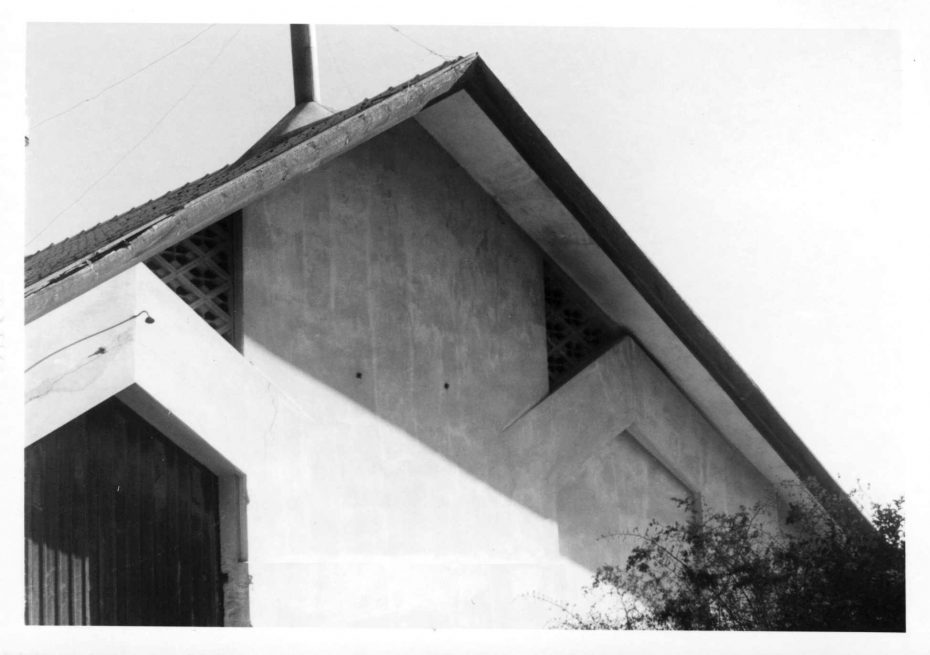

The Griffins would take on a number of projects in Australia, including the community of Castlecrag in the 1920s and the Capitol Theatre in Melbourne. Marion drew inspiration from the rich colours of the Australian landscape and was incredibly interested in the relationship between nature and the manmade world.

Much of Marion’s work can now be seen as incredibly forward thinking, intertwining nature with her design concepts and promoting what can now be described as landscape urbanism. However, when Walter died in 1937 and Marion returned to America, much of her work was simply forgotten.

Most historians looking back on Marion’s life abruptly cut it short after Walter’s death, who died 24 years before Marion. This however simply isn’t the case as Marion carried on lecturing, designing and writing, even penning her own memoir which would sadly remain unpublished.

Marion’s life ended as she battled dementia and ultimately died a pauper in 1961 at the age of 90. Her death certificate mistakenly lists her as a “Teacher in a Public School” and her marital status as “never married.” There is now a small plaque in memory of her at Graceland Cemetery.

History has tried to forget Marion and the mark she left on this world, but now more than ever it is time to unearth the stories of pioneering women and make space for them to be heard.