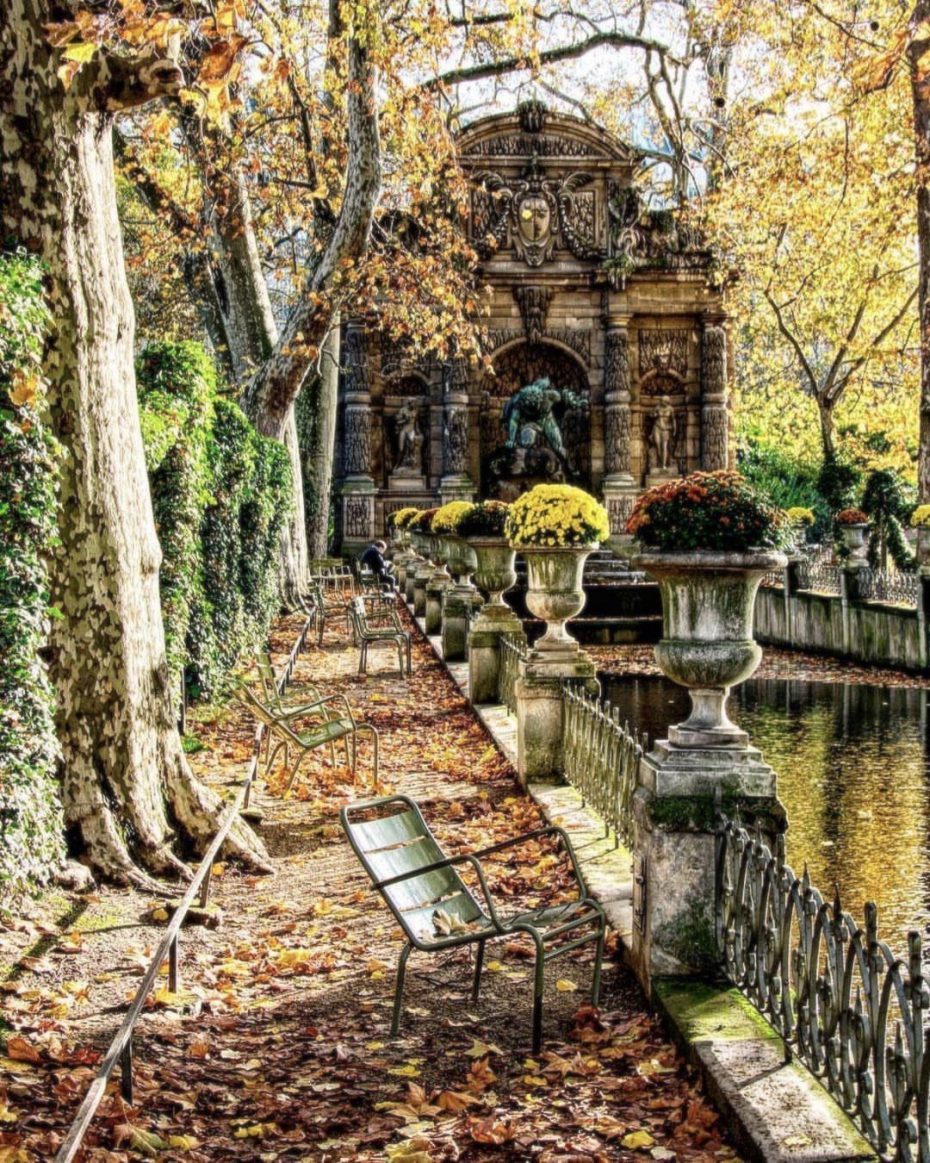

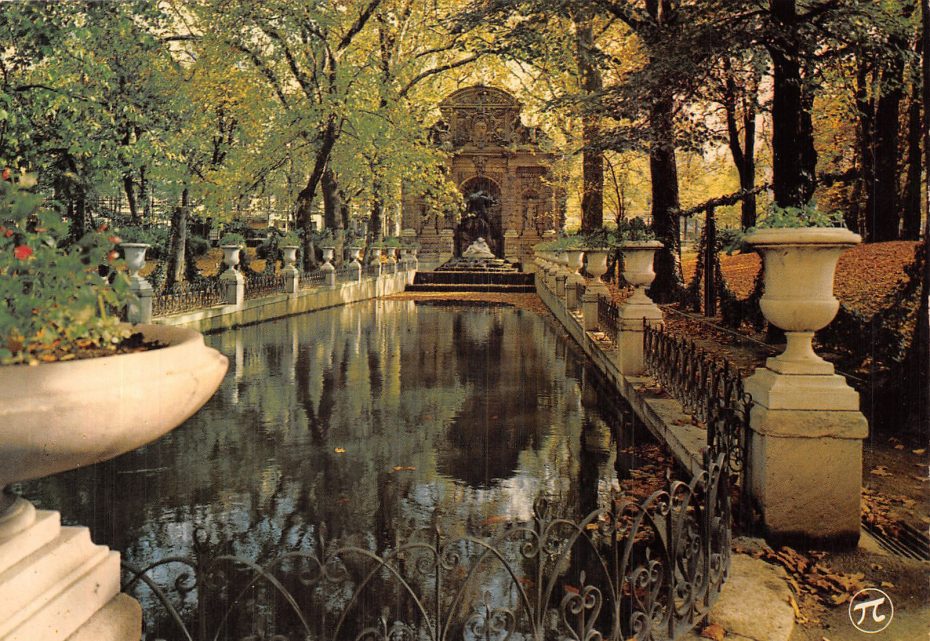

As if plucked from a 17th century Mediterranean estate waiting to transport Parisians to the hills of Florence; tucked away in a corner of Paris’ Luxembourg gardens is one of the city’s most underrated beauty spots. The Medici Fountain, crowned with an Italian grotto and flanked by ivy drapes, is an impossibly romantic place alluding to the story of a troubled, homesick queen. In fact, throughout the iconic Jardins de Luxembourg, you’ll find clues to the legacy of a woman far from home, nostalgic for the surroundings of her beloved Florence. And this forgotten Italian connection is perhaps most evident in the near-replica of a Tuscan palace she had built right at the heart of Paris’ most famous park…

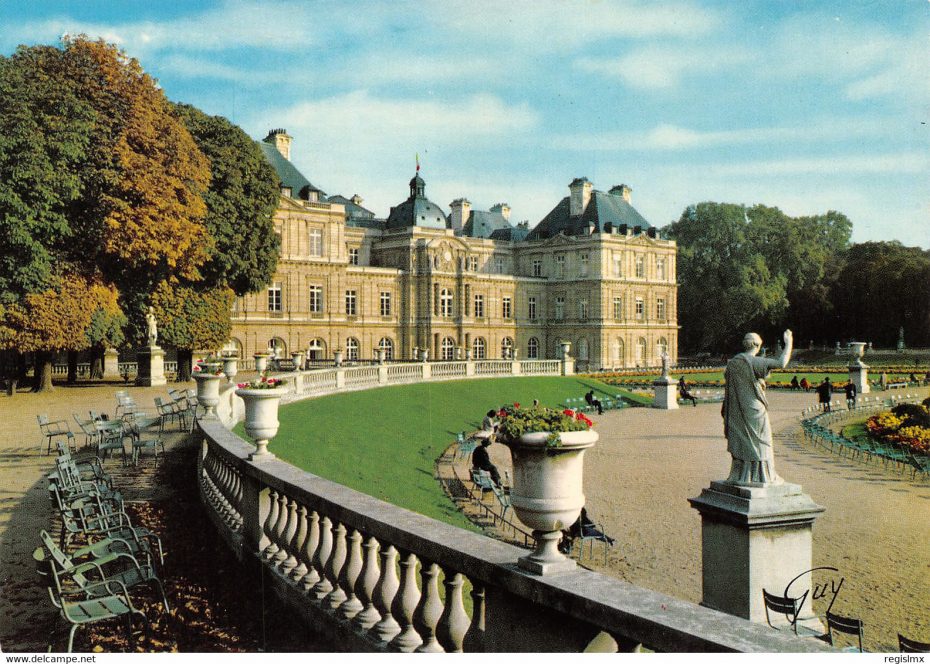

The Palais du Luxembourg may not be up there with the most iconic of Parisian landmarks, taking a backseat to the Eiffel Tower and the Sacré Cœur when it comes to the sites that visitors traditionally flock to. Home to the French Senate since the 1950s, on a Sunday afternoon, you’ll find dapperly-dressed children sailing toy boats out on the front pond and couples strolling arm in arm enjoying the surrounding gardens, largely unaware of its intriguing Italian backstory.

You could indeed be forgiven for thinking that this typically Parisian scene is the result of just another French regent with expensive taste, but this extravagantly ornate palace with all its lavish embellishments is in fact modelled on the Tuscan childhood home of an Italian princess, Maria de’ Medici, who incidentally became France’s most hated queen.

Marie de’ Medici (born Maria) was a member of the notoriously powerful Florentine banking family; the daughter of Francesco I de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Her childhood was filled with the sort of tragedy and scandal one might expect from a Brothers Grimm fairy tale. When Marie was just a toddler, her mother, the Archduchess Joanna of Austria fell to her untimely death while heavily pregnant with her unborn child. Her deathbed was still warm when Marie’s father took up with the woman who would become her stepmother (many suspected that his late wife’s unfortunate tumble may have been more of a push). The Grand Duke however didn’t have to endure the suspicion for very long because within a few years, both he and his second wife were dead too – some historians say they were poisoned by Marie (hence her historical nickname: the “Poison Queen”), while some believe they were killed by malarial fever. Whatever their cause of death, it now made Maria de’ Medici the richest heiress in Europe.

Despite her rather morbid reputation, Marie still remained somewhat of a hot prospect on the royal European dating scene thanks to the significant newfound wealth. The fact that she was also considered quite the looker didn’t hinder her chances either. When Marie got wind of France’s King Henry IV’s interest in her hand in marriage, she was keen to accept her prestigious suitor. The wedding of Marie de’ Medici and the French King was an exuberant affair, held in Florence and attended by hundreds of guests, who were treated to a newly-invented genre of musical entertainment called opera. The only minor drawback was the lack of a groom. You see, King Henry was not actually present at his wedding. Instead the marriage was carried out by proxy, so even on her wedding day, Marie had still not met her future husband. Despite the rather peculiar start, when she arrived in Paris for the first time in 1601, Marie was already pregnant, and a few months later, the future King Louis XIII of France was born.

But the marriage itself wasn’t exactly the fairy-tale ending that we might have hoped for Marie after the trauma she had endured in her childhood. King Henry might have been one of the most powerful men on the continent but like many men in positions of power, he had a weakness for women. His reputation as a professional philander was well known across Europe, leaving behind a medley of mistresses and illegitimate children in his wake. In fact, one of his most famous lovers, Henriette d’Entragues gave birth to a son just a few months after Marie. Henry had a habit of getting his mistresses pregnant at the same time, and seemed to enjoy watching their cat fights play out publicly, much to the delight of gossip-hungry courtiers. His legitimate and illegitimate children were raised together and Henry was often seen dining at the Louvre with both his wife and his mistresses together. There’s an entire Wikipedia page dedicated to his notoriously tangled love life. Perhaps his portrait’s smugness says it all…

The French court treated Marie with about as much respect as the King did himself, and despite bearing him six children in total, he initially refused to make Marie his Queen. Following the King’s lead, the French court regarded Marie as a foreigner and treated her with disdain. But after a decade of pleading with him, Henry finally organised Marie’s coronation, though his motives were somewhat more practical than compassionate. Headed off to war, Henry needed his wife to act as regent over the country in his absence. Little did he know that karma had wicked plans for him – because the day after Marie finally got her crown, King Henry IV was assassinated.

In an even more ironic twist of fate, Henry’s carriage was stuck in Marie’s post-coronation traffic when the assassin attacked him. Rumours of course circulated that Marie had had a thing or two to do with Henry’s untimely death, doing no favours for her popularity in France.

Following her husband’s death, Marie became the official ruler of France, entrusted with the job until her son Louis became of age. In the short time she had, Marie certainly got to work. Having been living in what she considered a shabby and run-down Louvre palace, Marie was desperate to create a pied-à-terre of her own. So she set about creating the Palais du Luxembourg, formerly known as the Palais Medici.

Nostalgic for Italy, Marie chose to model this decadent building and the 25-hectare park on her childhood home, Palazzo Pitti (above) and sent her architect to Florence to make notes on how to recreate it for her in Paris. The Tuscan influences would act as early precursors for Chateau de Versailles and the Chateau de Vaux-le-Vicomte.

Marie now had her moment to shine, and shine she did. The Queen commissioned a decadent central staircase and sumptuous apartments for herself, adding matching suites for her son and future King of France, Louis XIII. She continued the legacy of Medici art patronage by commissioning 24 works by the renowned Peter Paul Rubens, who was commissioned as her personal portrait painter. He painted her as almost godlike, depicting her in poses of strength, poise and determination; images that were at the time mostly reserved for war heroes. These paintings are now known as the Marie de Medici cycle and hang in the Louvre.

Whilst Queen Marie brought glory to France in some ways, such as financing the expedition of Samuel de Champlain to North America, which resulted in France laying claim to Canada, she was largely uninterested in politics. As a result of her shaky authority as Queen, there were many attempts to overthrow her, most notably by her son, Louis. When he came of age, Marie had flat out refused to cede her power to her first-born child, so he went and organised a coup d’etat in 1617, dethroning his own mother and sending her to exile at the Chateau de Blois.

Marie remained a prisoner there for almost two years, when in 1619 she – get this – allegedly escaped the castle by scaling a wall with a rope ladder. Say what you will about Marie, but she was a fighter (with exquisite taste in art). She would ultimately claw her way back into the French court but despite her numerous attempts to take back the throne, Marie was eventually banished for good by her son Louis in 1631.

Medici died in 1642, in exile and comparative poverty in Cologne, far from both her homeland and the Italian Left Bank palace that she had built. Despite her adventurous story, she is not a historical figure many are familiar with, but her legacy lives on in her Luxembourg gardens. And technically, we also have Marie to thank for the palace of Versailles. You’ll find her statue among a series of 20 white marble queens that flank the the central gardens, in honour of the women who left their mark on France at a time when the circle of power was very much a man’s world.

And of course, you’ll find her Florentine fountain, one of the most romantic hideaways in Paris, where ducks bathe happily under the stone nymphs; a heavenly slice of Italy in the heart of the capital.