If Norma Shearer doesn’t ring a bell like other legendary names of the silver screen might, then you too, have fallen victim to the Hays Code. Before we even knew it as “Hollywood”, the American film industry was producing a surreal amount of extraordinarily liberal and racy movies dominated by strong unapologetic female characters, homosexual characters, nudity, sex, drugs and taboo subjects like abortion. But everything changed in the year 1934, when a strict moral code laid out by a government-hired presbyterian pastor, known as William Hays, began dictating the way Hollywood – and America – would behave for generations to come. The longterm impact of the Hays Code on American culture is perhaps only now coming to light. With the way that movies and television have programmed our understanding of history, world view and our denial of “darker” elements for so long, we’re only just beginning to understand how its censorship might have changed the course of history. By all accounts, Norma Shearer was the queen of pre-Hays code film. “The first American film actress to make it chic and acceptable to be single and not a virgin on screen,” she should be considered a feminist icon today for her pre-code career and her portrayal of women’s sexuality. So with Oscar season upon us, let’s talk about the woman whose name has been buried in Hollywood history.

Norma arrived down and out in New York City in 1920 with her mother and sister, hoping to land herself part in the glamorous world of the Ziegfeld Follies. Her father’s company had collapsed after WWI, plunging her family into poverty and she suddenly found herself scraping by in the big city, taking turns with her sister to sleep in a bed. When she auditioned for Harold Zeigfeld at the age of 18, he turned her down quite brutally, allegedly calling her a “dog” and assuring her she’d never make it in show business. Norma had a condition called strabismus; her left eye had a tendency to wander and she didn’t have the conventional figure of a showgirl. But Shearer was too ambitious to let any of that stop her.

She spent the next few years playing bit parts in silent films, pulling tricks, like coughing to grab a producer’s attention as he walked past a line of hopeful starlets. She relentlessly practiced her best angles in the mirror, and even had surgery to fix the cast in her right eye. Shearer finally got her ticket to Hollywood in 1923 when she caught Louis B. Mayer’s attention with her role in a B movie, landing her a contract with the studio. In two years, she went from being an unknown contract player to one of MGM’s biggest stars, often playing the role of a spunky, sexually liberated protagonist. In 1927, the rising star married her boss, studio producer Irving Thalberg. He proposed to her under a monkey tree in the Coconut Grove nightclub and their union was the Hollywood wedding of the year.

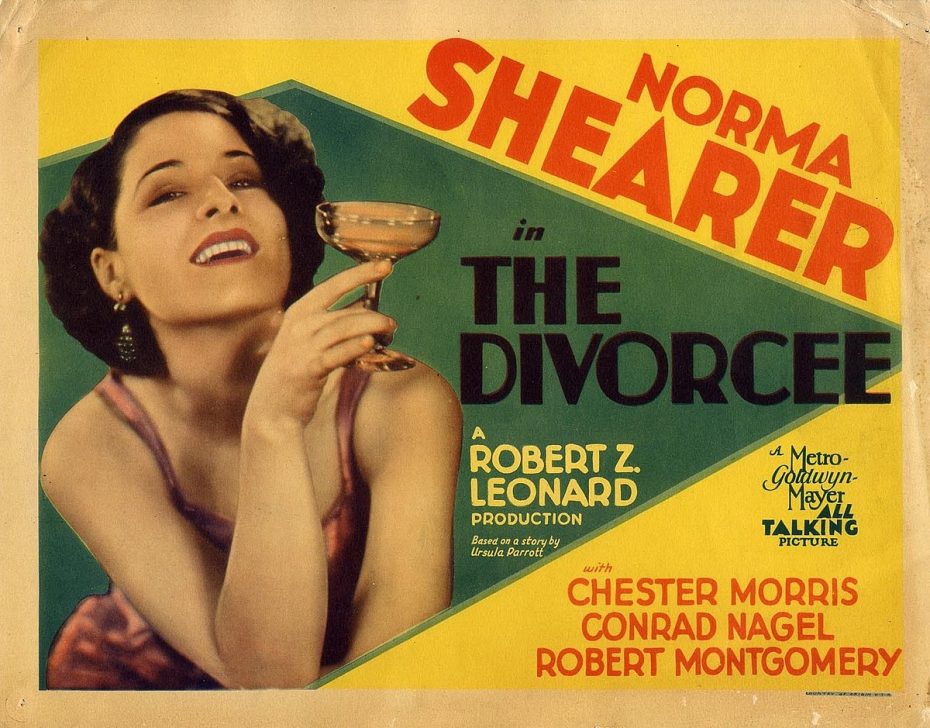

The role that eventually won her an Oscar almost wasn’t given to her. Shearer’s own husband initially did not want to cast her in The Divorcee because he didn’t believe she had the sex appeal. She took it upon her self to organise a boudoir photo shoot to convince him that she could be cast as the sensual lead in The Divorcee.

Her character in the film was that of a wife who discovers her husband’s affair and seeks to settle the score with an adulterous tryst of her own, challenging the double standards of marriage. In the pivotal pre-code film, Shearer played Jerry to be a sympathetic character, someone strong and rather than a bitter and vindictive woman.

She was “the exemplar of sophisticated 1930s womanhood,” wrote film historian Mick LaSale, “exploring love and sex with an honesty that would be considered frank by modern standards.” Norma was able to help change the way women were viewed on screen and with The Divorcee, among other films, she helped pave the way for the likes of Mae West and Jean Harlow.

Multiple films starring Shearer have a similar plot to The Divorcee, or at least feature women owning their sexuality without remorse, for revenge or pleasure. Shearer controlled her choices and her body. Right after The Divorcee, Shearer played the role of an unassuming housewife who reinvents herself when her husband leaves her in Let Us Be Gay (1930). At the time, the idea of portraying a married couple finding happiness apart was pretty scandalous. Private Lives in 1931 followed the story of a recently divorced couple who decide to honeymoon with their new spouses at the same hotel.

Expressing a similar sort of sexual freedom, in A Free Soul (1931) Shearer plays the character Jan, as a woman who is in full control of her actions and freely enjoys having pre-marital sex. In a post-code film, she would probably have been killed off in the script to pay for her “sins” but the movie hinted women that they had more options than they typically considered.

She was once in the running for the role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind. Many thought her unsuited to the role so she opted to remove herself from consideration and joked, “Scarlett is a thankless role. The one I’d really like to play is Rhett!”

Off-screen, Norma and her husband became one of Hollywood’s biggest power couples and were known for having legendary soirees. Writer F. Scott Fitzgerald is said to have based the story of “Crazy Sunday” on one of Shearer and Thalberg’s parties and the story’s protagonist, Stella Calman, on Shearer herself.

She was frequently pitted against other stars like Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, and Jean Harlow as MGM’s top actress and her confidence is said to have rubbed many of them the wrong way. “It is impossible to get anything made or accomplished without stepping on some toes,” Shearer once said, “enemies are inevitable when one is a doer.” She and Crawford had a bitter and long-standing public rivalry which was eventually played out onscreen in The Women.

The talkies spelled the end of many silent film careers, and Shearer was determined hers would not be one of them. In The Trial of Mary Dugan, Shearer showcased her voice to her fans for the first time. She and her brother, a sound designer, were the first brother and sister to both win Oscars. Before this film, Shearer trained with her brother for two years to prepare herself for the microphone.

Shearer loved the screen image crafted for her by her husband that was one of an independent, sexualized, modern woman. Her public persona meanwhile, was that of loving wife and the “first lady of MGM.” Her pre-code roles were also very different from Shearer’s private life. Her husband had a heart condition, and Hollywood historians write about the sexual frustration Shearer must have experienced: “Too loyal and prudent to risk an affair in life,” they say, “she could at least escape into the illusion of sexual adventure on the screen…that happened to satisfy thousands of wives in the audience…”.

When the Hays Code started to be enforced, she quickly went from sensual actress to prestigious actress, but the roles she was offered were shadows of the women she had once portrayed pre-Code.

After her husband’s death in 1936, Shearer struggled to continue in acting. She tried to adapt to the changing times at MGM, but she resisted playing older, matronly roles. During the Great Depression, women’s roles in films transitioned from glamourous, sexual women to the the ideal housewives and mothers, which Shearer did not want to play.

When MGM tried to contest her late husband’s payments for his films to his estate, she took one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, Louis B. Mayer, who has been compared to a 1920s Harvey Weinstein. She won the fight for over $1.5 million in percentage payments while maintaining her tactfulness, grace, and public sympathy throughout the ordeal. And as a result, the public began criticising the greediness of the MGM studio heads. But her industry showdown against Mayer likely contributed to her decline in roles and eventual retirement from film and the Hollywood social scene.

By the time of her death in 1983, Shearer’s legacy was entirely overshadowed by her more “noble” roles in films like Marie Antoinette and The Women. Her pre-Code films are rarely televised, which is considered a great shame because those movies showcase her at her best – as a feminist film pioneer.

“An adventure may be worn as a muddy spot or it may be worn as a proud insignia. It is the woman wearing it who makes it the one thing or the other.”

Norma Shearer