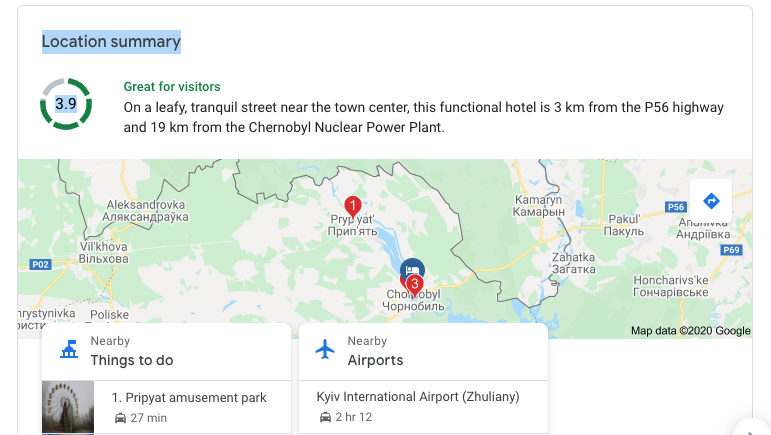

Look online and the Hotel Desyatka appears on booking sites like most other hotels. A quick Google search will tell you that it consists of, “Basic lodging on leafy grounds, offering a cozy restaurant/pub, plus free parking and breakfast.” There’s even a Trip Advisor entry complete with favourable customer reviews and its own website that advertises a hotel “on a tranquil street near the town centre, 3 km from the P56 highway.”

All of which seems quite pleasant until you read the rest of the hotel’s welcoming literature: “Remember your body is exposed to additional radiation exposure. Do not touch anything…they can be a source of trouble for you, your family and friends. Even strangers.”

This menacing sounding message is well served, for the Hotel Desyatka is located deep in the Exclusion Zone surrounding the infamous, stricken nuclear reactor in Chernobyl. Incredibly, the hotel is open for business. So we went to go spend the night in what might be one of the world’s most unusual and remote hotels.

For intrepid visitors to Chernobyl, a day trip alone seems risky enough: multiple military checkpoints guard one of the most radioactive places on earth. With a nightly curfew, and a considerable traveling distance from Kyiv, most trips to the Exclusion Zone don’t allow for much more than an afternoon in the disaster area. These organised tours mostly stick to Pripyat, the city where most of the nuclear plant workers lived, and where you’ll find the now-iconic abandoned Ferris Wheel and funfair.

But the Exclusion Zone itself is a vast area of just over a thousand square miles, and home to around a hundred other less famous villages, towns, railway stations, and Soviet military bases, which the rapidly deteriorating roads have left mostly undisturbed.

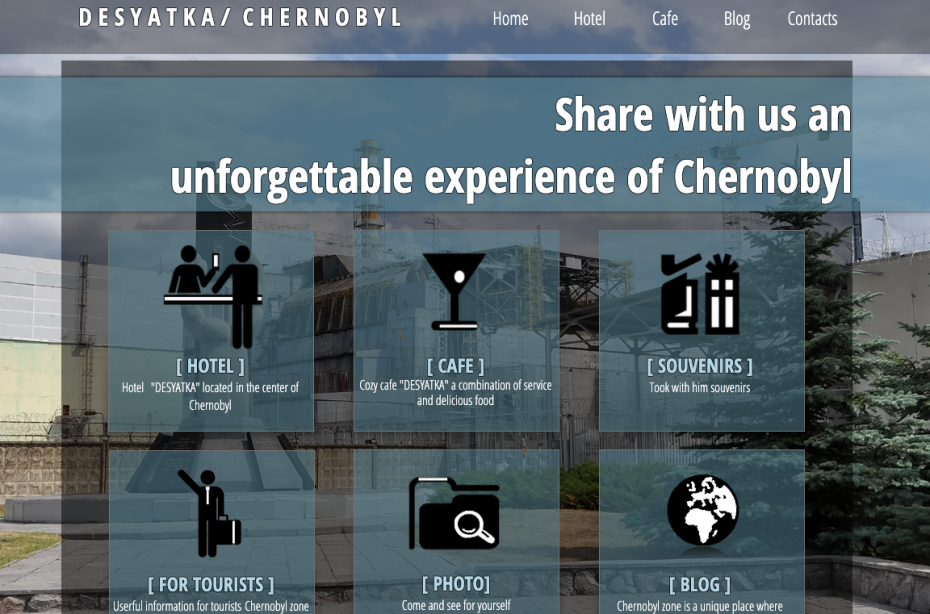

To reach these other worldly areas, several tour groups offer multiple day visits into the Zone, and that means staying the night at the Hotel Desyatka.

Like other hotels, the Desyatka has the usual guest amenities: a café and restaurant, a bar and even wifi, which means you can enjoy the unusual experience of sending emails from one of the most cut off places on Earth. But as the welcome guide explains, “There is no concept of ‘hotel for tourists’ in the Zone, so one shouldn’t expect the usual service and facilities from such accommodations. Nevertheless there are good conditions for relaxing after a day of active exploration.”

The Hotel Desyatka is a small, two floor building, wrapped in yellow corrugated metal, that slightly resembles an oversized shipping container. But walk inside and you could be in any modest hotel; there’s a staffed lobby with maids walking the corridors and there’s even a wire rack on the main desk selling souvenir postcards. You have to remind yourself that you’re in the middle of nuclear wasteland caused by one of the world’s most infamous disasters.

The hotel itself is simple, best described as being in the ‘Soviet’ style. From the tour website: “Visitors are provided with the iron starched linen stamped by the Chernobyl special industrial complex.”

As with any prospective hotels, its worth studying the Trip Advisor reviews:

“For a start you are in the middle of Chernobyl, so this isn’t going to be the Ritz! It did the job for the few hours we were there. The bed was a bit on the soft side, but the duvet was super warm. The shower was excellent.”

“The food was OK, traditional Ukraine fare, and probably the only place you’d be glad to hear, hasn’t been locally sourced! Rooms are basic but comfortable, and although no en-suites, there are plenty of bathrooms available. I left the next morning positively glowing…….or perhaps that was the radiation!!!!!”

“Considering the location of the hotel, I was hugely impressed. The staff are very friendly, the food (breakfast and dinner) was of a high standard. If you are staying within the Exclusion Zone I highly recommend staying here!”

After checking in, we set outside the hotel to explore downtown Chernobyl, heeding the hotel’s advice: “Put a barrier in the way of radiation, wear garments with a minimum of seams and zippers. Change shoes you do not mind to throw away in the event of contamination. Wet wipes to wipe radioactive dust accidentally fallen.”

Whilst Pripyat, a few miles down the road, opened in 1970 as a model city for the youthful workers of the burgeoning nuclear reactor industry, Chernobyl has a far richer history, dating back to the 12th century, and as such, is filled with the ruins of many older buildings. Back then it was a vibrant, mostly Jewish town, with a population in 1900 of just over 10,000, that was decimated first at the hands of the Red Army following the Revolution, and then by a brutal Nazi occupation that saw Chernobyl suffer enough long before the nuclear disaster. Wander around the post-apocalyptic wasteland of Pripyat and you might bump into several other tour groups: the city of Chernobyl you are likely to have to yourself.

The city itself is divided roughly in two by a grass central square, in the middle of which is a pathway lined with signposts each bearing the name of one of the towns or villages that had to be abandoned over thirty years ago. Walk past and you’ll read the names of places like Yaniv, Kopachi and Vilcha, each with a red line drawn through them, as though they’d been struck from history’s records.

To the left lies the old part of town. Wide, leafy boulevards are lined with beautiful Belle Epoque era buildings, that must have once been a beautiful place for an evening walk. But like everything else in the Zone, the cosy looking family cottages and town houses are now in an advanced stage of decay.

Wander the deserted streets and you’ll find parks, a library, schools and children’s playgrounds. You’ll also find heart breaking reminders of the lives left behind; dolls, colouring books half filled in, worn teddy bears, and plastic toys.

To the right of the town square are the newer, Soviet buildings. Built in the Brutalist Communist style, you’ll find yourself in a town frozen in time from before the break up of the Soviet Union: hammer and sickles still adorn the street lamps and public buildings, and standing sentinel outside the government building is a statue of Vladimir Lenin.

Quite surprisingly, amidst the decay and abandonment, you can still find small traces of daily life. There’s a daily workforce of several thousand, mostly employed in the sarcophagus project that was constructed over the leaking reactor, as well as scientists conducting experiments in the unique conditions, and dotted around the desolate landscape, a handful of elderly residents who never wanted to leave their ancestral homes.

The town museum still opens occasionally and there’s a post box that still makes a daily collection at noon. There’s even a supermarket still open, although its shelves are sparsely stacked with goods, reminiscent of the Soviet era, and most of what’s on sale is vodka. Even more surprisingly, there are still people shopping here. Workers in the Exclusion Zone operate on a strict rotation pattern of fifteen days in and fifteen days out, to keep their radiation levels manageable, staying in concrete dilapidated dormitories next to the Hotel Desyatka, which also means that there are chefs, maids and bar staff on hand at the hotel – the only place in Chernobyl open to eat and grab a drink in the evening.

“We will help you relax after a long excursion” promises the hotel website. “Take a break after work….relax with friends over a glass of beer,” all of which is an ideal way to decompress after exploring the nightmarish world outside the hotel door. Although presumably not many people are taking up the hotel’s offer of being a place “to celebrate an anniversary”.

Dinnertime in the hotel doesn’t come with a menu, but traditional Ukrainian food is promptly served, without an option. Borscht soup, plates of breaded chicken, plain potatoes and corn, red cabbage and carrots, are accompanied by two types of synthetic squash juice. As one Trip Advisor reviewed;

“There’s no choice at mealtimes, and service is rather unsmiling, but the food itself – although not fancy – is tasty, nicely presented and there’s a lot of it.”

Its easy to get caught up exploring the abandoned secrets of the Exclusion Zone. Sometimes its as if Chernobyl has become Europe’s largest urban adventure, especially since the excellent HBO show from 2019 that saw a huge increase in the number of visitors. Sometimes you forget the vast human and natural cost of the disaster. From those who died battling the explosion, to the generations suffering from thyroid cancers, to the huge swathes of natural landscape and wildlife still enveloped in radiation. “Remember how many people in this city have given their health and lives to you to live today,” explains Alexander E. Novilov, Deputy Technical Director of Chernobyl NPP for Security on the Hotel Desyatka website.

For a brief reminder, here’s Pripyat 3 months after the disaster:

There is a strict curfew in the Zone that sees the bar close at 10pm (pandemic or no pandemic). After dinner, we decided to wander around the empty town square. Spending the night in Chernobyl is as eerie as it is unsettling. Everything is silent apart from the occasional howls of from packs of wild dogs roaming the forest, and a strange sequence of rising electronic beeps coming from the scientist’s camp, buried deep in the woods a few miles north. When we return back to our hotel for a nightcap in the bar, ours are the only lights still on in the entire town.