For over 50 years, a 27-mile network of pneumatic tubes provided upwards of a third of New York City’s mail. Nowadays, speed is the name of the game, whether its technology constantly increasing the speed of digital communication or Amazon delivering goods at record rates. But 100 years ago, pneumatic tubes, basically 19th-century physical internets, were all the rage to send messages and goods underground, often in a matter of minutes. Most people are still unaware that NYC has those pneumatic mail tubes buried 4 feet underground – or in places you’d least expect…

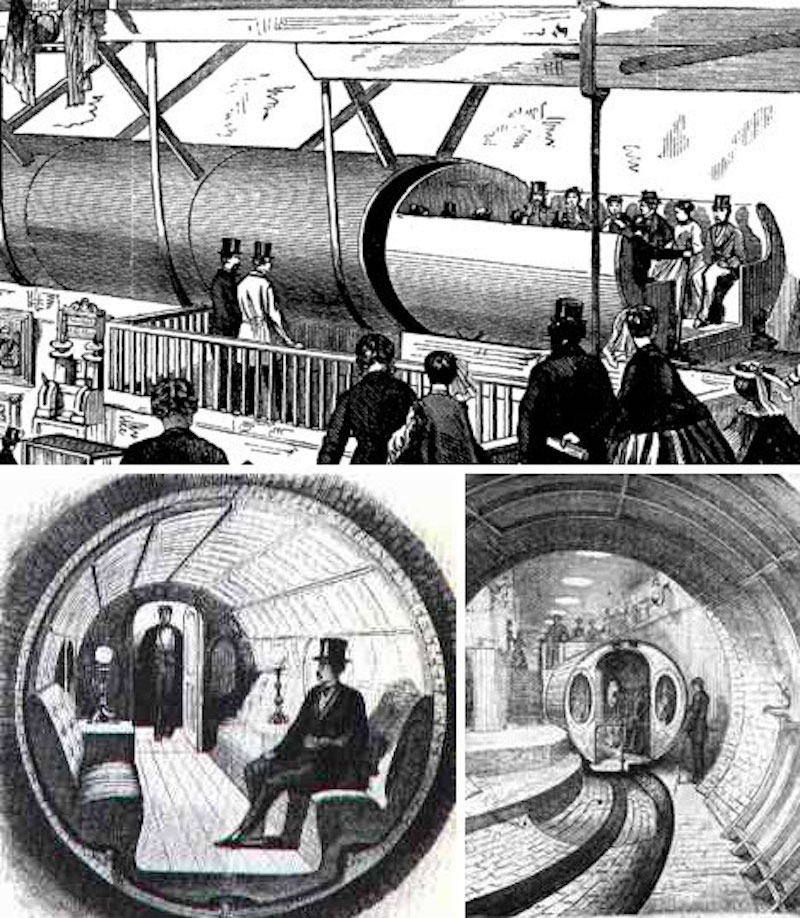

Invented by Scottish engineer William Murdoch, pneumatic tub transportation systems were first used for telegraphs in London in 1854, connecting the London Stock Exchange to the Electric Telegraph Company. This expanded all over Europe, to Berlin, Paris, Prague and

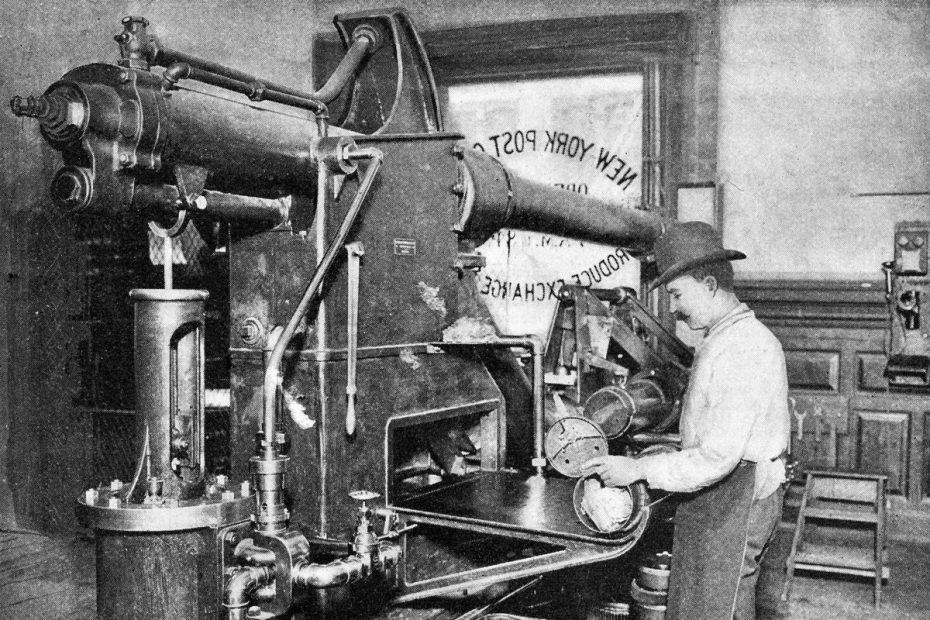

Vienna. Philadelphia was the first American city to adopt this system in 1893, with New York following in 1897, although New York had previously experimented with a pneumatic subway system. Over a hundred spectators including Post Office officials were present at the unveiling.

The first package was a Bible wrapped in an American flag and copies of the Constitution and President William McKinley’s inaugural speech. As post office worker Howard Wallace Connelly wrote in his autobiography, things quickly turned comical. An artificial peach was sent through the tube — a joke targeting politician Chauncy Depew who was the master of

ceremonies. (Hansen had previously been called a “peach”). The stakes were further heightened when a cat made the underground journey. As Connelly wrote, “ How it could live after being shot at terrific speed from Station P in the Produce Exchange Building, making several turns before reaching Broadway and Park Row, I cannot conceive, but it did.”

Depew, for his part, described the pneumatic tubes as “the age of speed.”

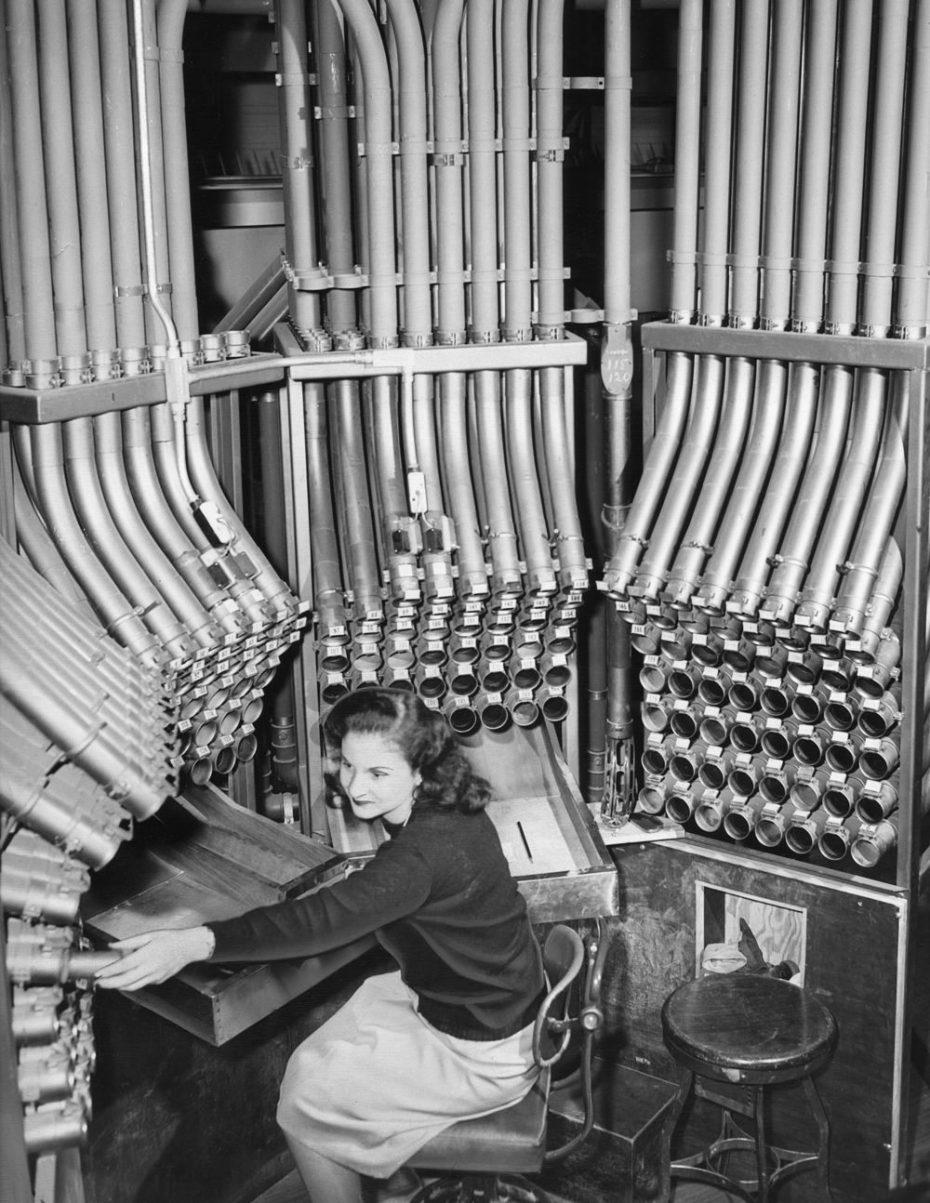

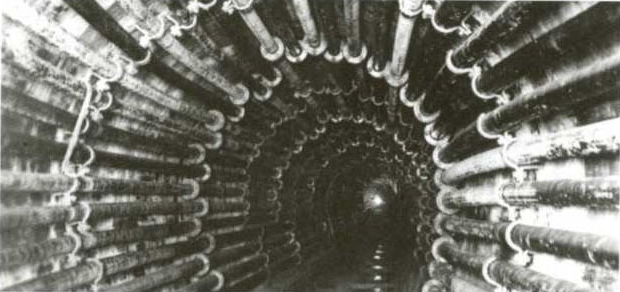

“Everything that makes for speed contributes to happiness and is a distinct gain to civilization”, he said at the dedication. The tube mail system was located 4 to 6 feet underground, with rotary blowers and a

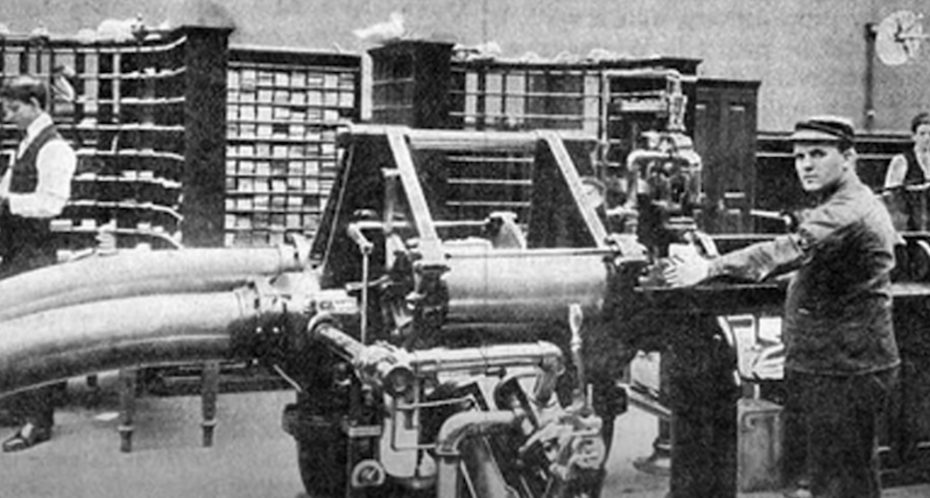

compressors providing the air pressure (around 3 to 8 pounds per inch) that could move the 25-pound steel tubes at average speeds of 30-35 mph.

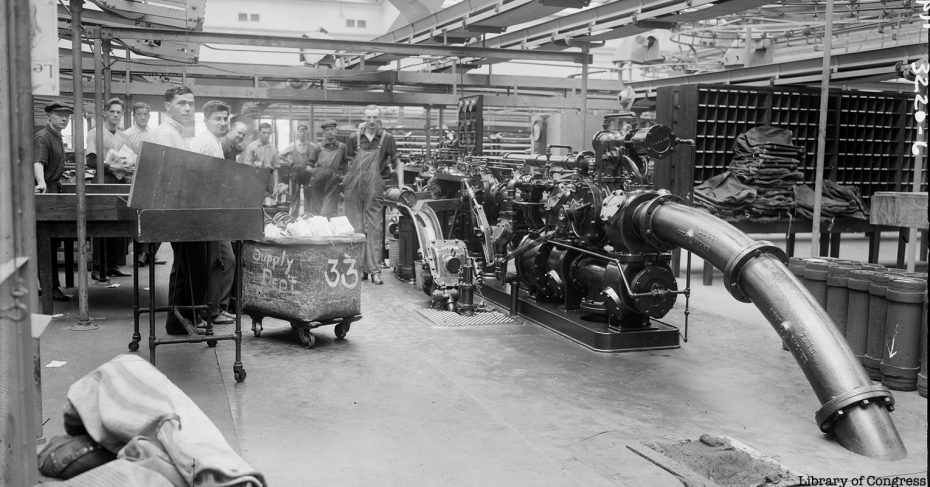

At 24-inches long and 8-inches wide, these cylinders could hold up to 600 letters. A team of 136 “Rocketeers” and dispatchers made sure the

system ran smoothly, transporting upwards of 95,000 letters per day.

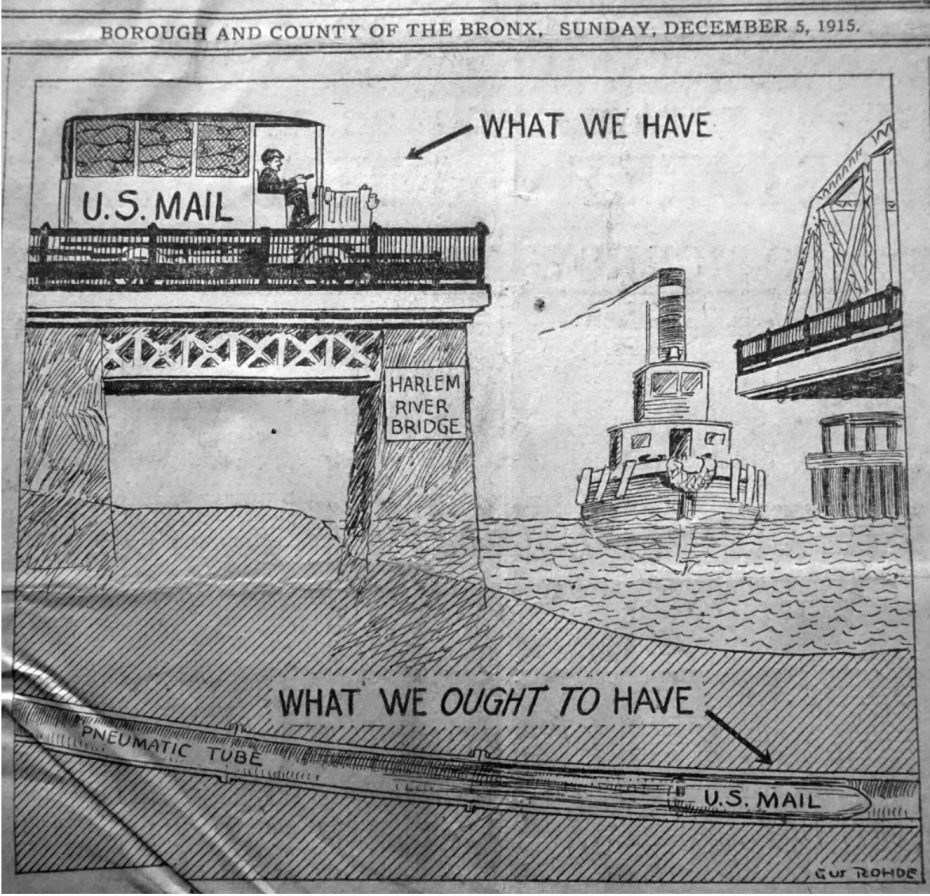

The original tubes were less than a mile long, from the old General Post Office to the Produce Exchange. It quickly grew to cover both sides of Manhattan Island with a crosstown line. Extensions were added to the Bronx and Brooklyn using the Brooklyn Bridge. There is even a rumour that a popular Bronx sandwich shop used the system to send their sandwiches – the real submarine sandwiches! It took only 20 minutes for a canister to travel from the General Post Office to Harlem. A 40-minute mail wagon route was reduced to 7 minutes.

Despite its speed, the pneumatic mail system proved to be an expensive operation to upkeep. The federal government was required to pay an annual rental payment of $17,000 per mile in 1918. Service was halted during the first World War to save on costs, but the tunnels continued to prove resilient. During the Great Blizzard of 1947, which saw a record 26.4-inches start falling over Christmas, the tubes meant holiday gifts and letters could still be delivered.

As the population of New York City continued to grow however, the system struggled to meet increasing mail needs; the federal government had to pay private companies to dig and lay pipes and their reach was limited because of existing gas and sewage lines. Further, breakdowns were not uncommon, requiring streets be dug up to recover clogged mail. The tube size also limited the type of mail and there were frequent complaints of water and oil damage to the letters.

The beginning of the end of the system came in April 1950, when the line to Brooklyn was disconnected due to bridge repairs. In 1953, the recently inaugurated President Dwight. D. Eisenhower appointed Arthur Summerfield as postmaster general. Summerfield ceased all pneumatic mail services and switched to the more economical automobile-driven delivery system still in use today.

As reported in Wired, “Conspiracy theorists allege that the pneumatic tube system was dismantled primarily to sell a new fleet of General Motors delivery trucks to the city of New York.” (Summerfield did own a GM dealership). While certain places like Paris kept their pneumatic mail system into the 1980s, most became archaic in the age of more efficient technology.

But in an era when attention has shifted to sustainable and green energy processes, some tech innovators are reconsidering the pneumatic tube’s potential (take Elon Musk’s proposed Hyperloop for superfast human transportation).

With some of New York City’s pneumatic tubes still in place, projects have been proposed to bring them back into use, including for a fiber optic cable system. And if you go to Old Chelsea Post Office or the New York Public Library (hint: Humanities and Social Sciences department) and look hard enough, you can still spot remnants of the pneumatic system.