In the most arid part of Aragon, a northeast state of Spain, a ghost town with an unusual history waits to be explored. In a country full of vibrant traditions and an active monarchy, a small ruined city may seem unworthy of a place on the itinerary, but Belchite’s history is more than meets the eye.

Perhaps most well-known as a filming location for movies such as Pan’s Labyrinth, The Adventures of Baron Münchhausen, and most recently Spider Man: Far From Home, but more than a picturesque backdrop, Belchite has a darker history. An ancient town turned 20th century battlefield, to put the ruins of this into historical perspective, here’s a quick lowdown on the region…

All of Spain is beyond ancient. Cave paintings and prehistorical artifacts practically cover the “bull skin” of Spain, as Spaniards poetically call the shape of their country. The Romans were her in the first century CE, then the Goths and then the Islamic Kingdoms which brought a cultural renaissance.

Belchite was conquered in 1117 by the memorably named Alfonso the Battler, who gave himself the title of Emperor of Spain and founded an experimental community of knights who vowed “never to live at peace with the pagans but to devote all their days to molesting and fighting them”. Neato. So anyway, the ruined sanctuary of the town you see now was originally built in the 1500s and expanded in a hybrid style known as Mudejar, owing much of its beauty to Islamic architecture. The desolate landscape of the region left a mark on Goya, one of the most famous Spanish artists of the 18th and 19th century, who was born near Belchite and protested the tragedy of war in Spain with a series of engravings.

Belchite’s demise came during the Spanish Civil War, also referred to as the “dress rehearsal for WWII.” Soon after the infamous bombing of the northern town of Guernica in 1937, forever associated with Picasso’s famous large-scale painting, Belchite was bombed by Soviet aircraft and captured by the Republic army. The town was held by Nationalist forces supported by Italian fascists and Nazi Germany, whose troops were almost entirely wiped out.

Ernest Hemingway reported the battle of Belchite during his career as an American war correspondent…

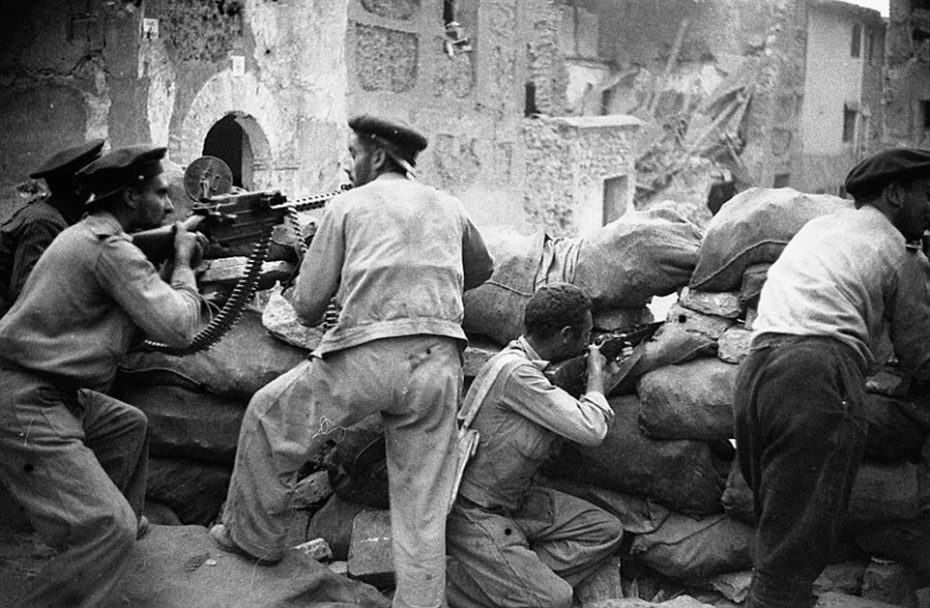

“When we got up with the Americans they were lying under some olive trees along a little stream. “The yellow dust of Aragon was blowing over them, over their blanketed machine guns, over their automatic rifles and their anti-aircraft guns,” he wrote.

“Since I had seen them last spring, they have become soldiers. The romantics have pulled out, the cowards have gone home along with the badly wounded.” Hemingway was one of the first American correspondents to arrive on the scene.

“Those who are left are tough, with blackened matter-of-fact faces … for three days they fought from house to house, from room to room, breaking walls with pickaxes, bombing their way forward as they exchanged shots with the retreating Fascists from street corners, windows, rooftops and holes in the walls. Finally, they made a juncture with Spanish troops advancing from the other side and surrounded the cathedral, where 400 men of the town garrison still held out. These men fought desperately, bravely, and a Fascist officer worked a machine gun from the tower until a shell crumpled the masonry spire upon him and his gun. They fought all around the square, keeping up a covering fire with automatic rifles, and made a final rush on the tower. Then, after some fighting of the sort you never know whether to classify as hysterical or the ultimate in bravery, the garrison surrendered.”

The bloody civil war between 1936-1939 resulted in a victory for the Nationalist forces and installed Francisco Franco in power as dictator for the next 30 years. First person accounts of the fighting were sent around the world almost immediately through the work of reporters like Hemingway interviewing volunteer soldiers.

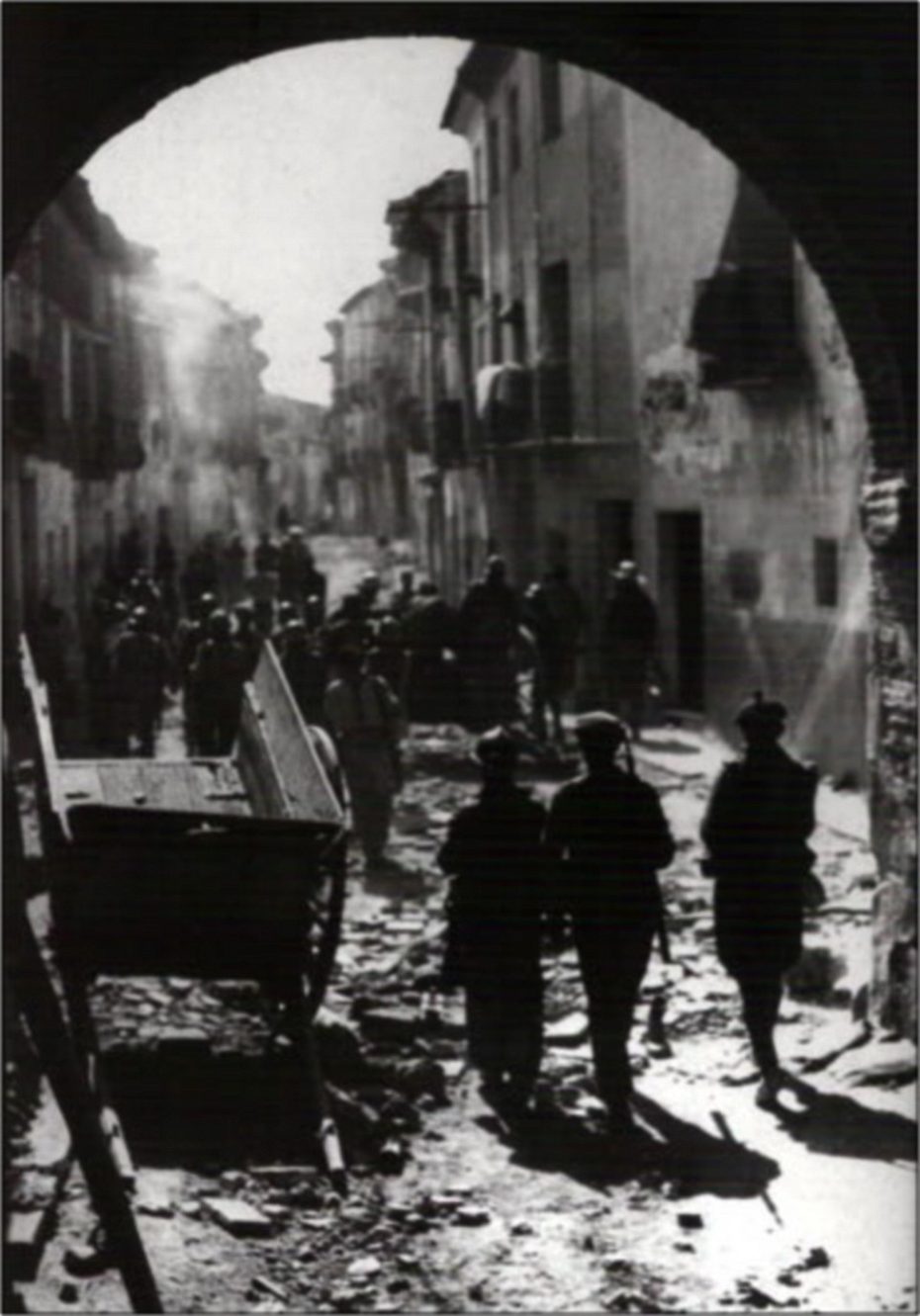

One Scottish volunteer, Hugh Sloan recalled: “You were seeing the person you were killing. That’s a different thing from killing people at a distance. In that respect it was a very bitter battle. I remember walking up what you could call the main street and I couldn’t bear the smell of death. We came to the square. There was a very large heap of dead human beings piled up. And in the very hot weather the smell was completely unbearable.”

Historian Cecil D. Eby writes, “[the journalists] found a town so totally ruined that often one could not tell where the streets had been. People were digging under piles of mortar, bricks, and beams pulling out corpses. Mule carcasses, cooking pots, framed lithographs, sewing machines—all covered with flies—made a surreal collage. Belchite was less a town than a nasty smell”.

While Hemingway had already invented the English-speaking world’s simplified perspective of Spanish culture through his fiction, the more complex reality was crushing down the residents of Belchite.

Resident Tomas Ortin remembered that he “and several thousand other Belchite residents endured the siege for almost two weeks, hiding in their cellars as soldiers fought hand to hand in the streets and artillery shells rained down.”

“‘There was a battle. Who lost? The people did,’ said Domingo Serrano, a former mayor who was born in the old town.”

The devastation rained on Belchite represents more than a total loss for a small Spanish community, it offers one of the first examples of Hitler’s reign of destruction that would crumble many iconic cities, such as Vienna, throughout Europe before his final defeat in 1945.

Carol Reed’s The Third Man film noir masterpiece, starring Orson Welles, was filmed in Vienna, while the city was still divided by four governments and in ruins in 1949. Bombed out cities seem to have always attracted film makers.

Most cities damaged in this way in the twentieth century were reconstructed, often as historically accurate as possible, but Belchite, by a whim of Franco, has been preserved as a witness to the arrival of aerial warfare. He intended it as a shrine to the brave dead who sacrificed for his “cause”. The new town of Belchite was built nearby by Republican prisoners of war under Franco’s orders.

Whether you visit Belchite someday in person or see it in a film, it’s unique history will only increase the pathos of the scenery. Those film makers may not even be aware, but you will.