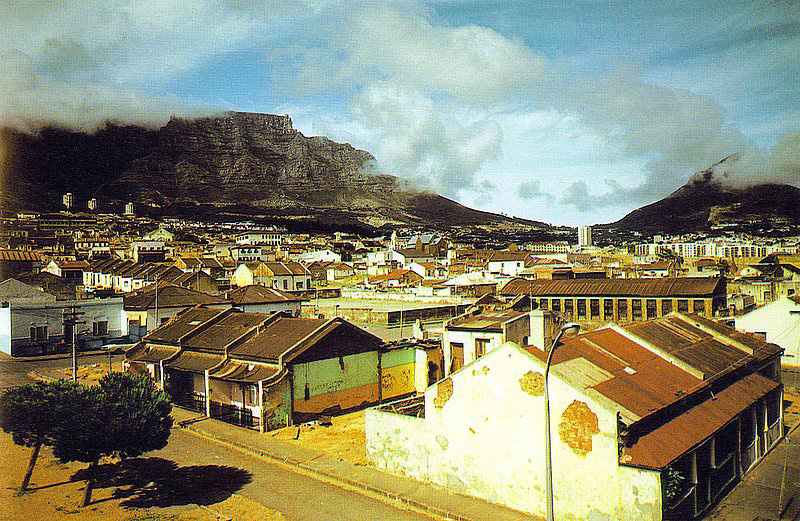

Once upon a time, at the southernmost tip of Africa, nestled in a hollow between the shores of the Atlantic Ocean and slopes of Table Mountain lived an awesome bourgeoning community of thespians. District Six was home to bohemians, artists, merchants, preachers, students, business people, gangsters and everyone in between. Think New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1950s, Paris’ Pigalle in the sixties or San Francisco’s Castro district in the seventies; a throbbing enclave comparable in vibrancy to the stomping ground of both the Lost Generation and the Beat generation put together. It was here in the centre of the District Six universe where a working class community’s joie de vivre transcended poverty and adversity; where diverse love stories played out and queer fashionistas strutted their stuff. Here was a place where people knew each other and everyone looked after everyone else’s children – until the apartheid wiped it off the map.

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

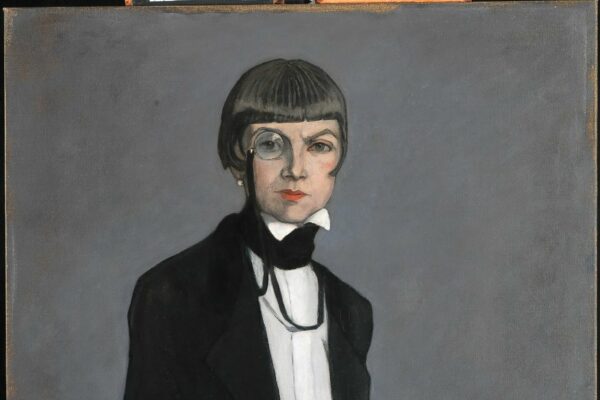

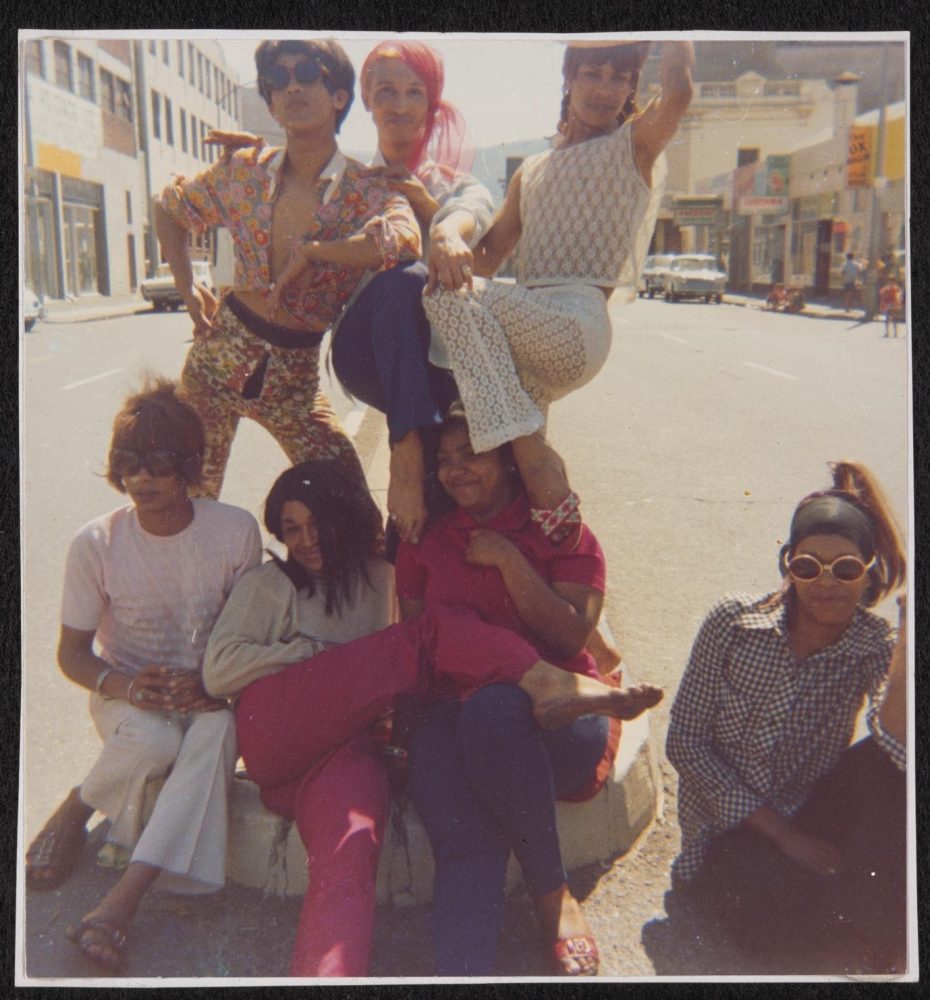

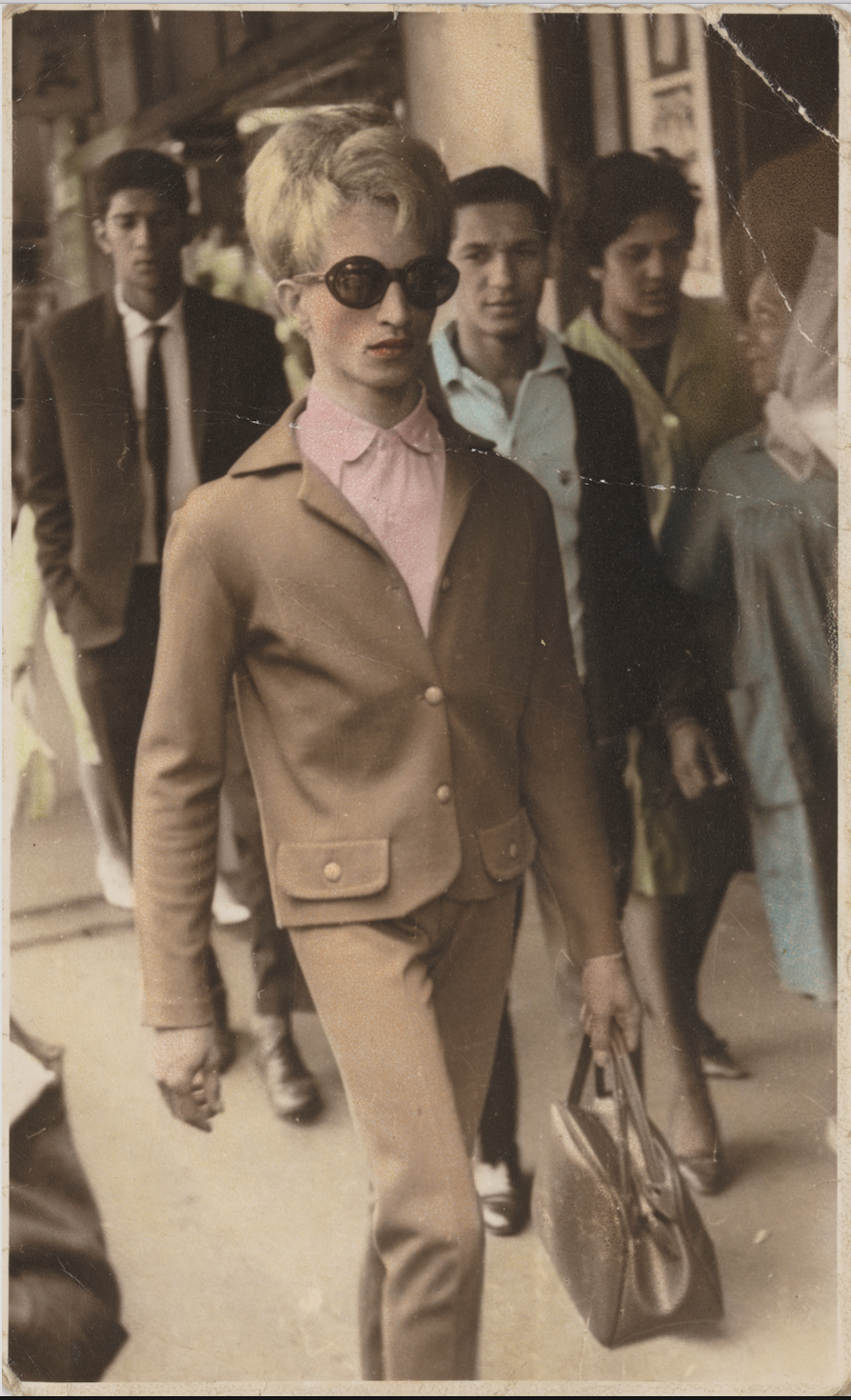

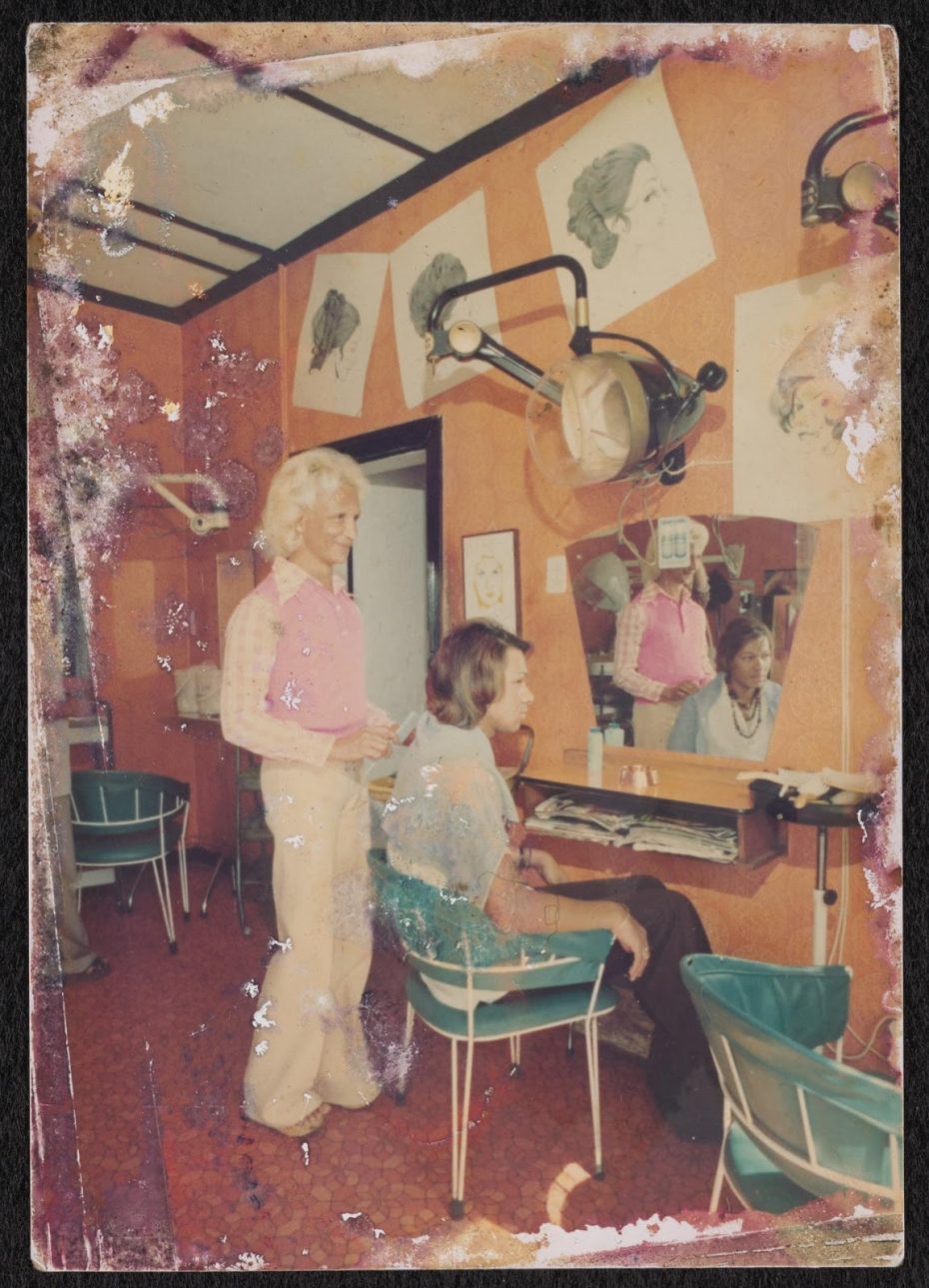

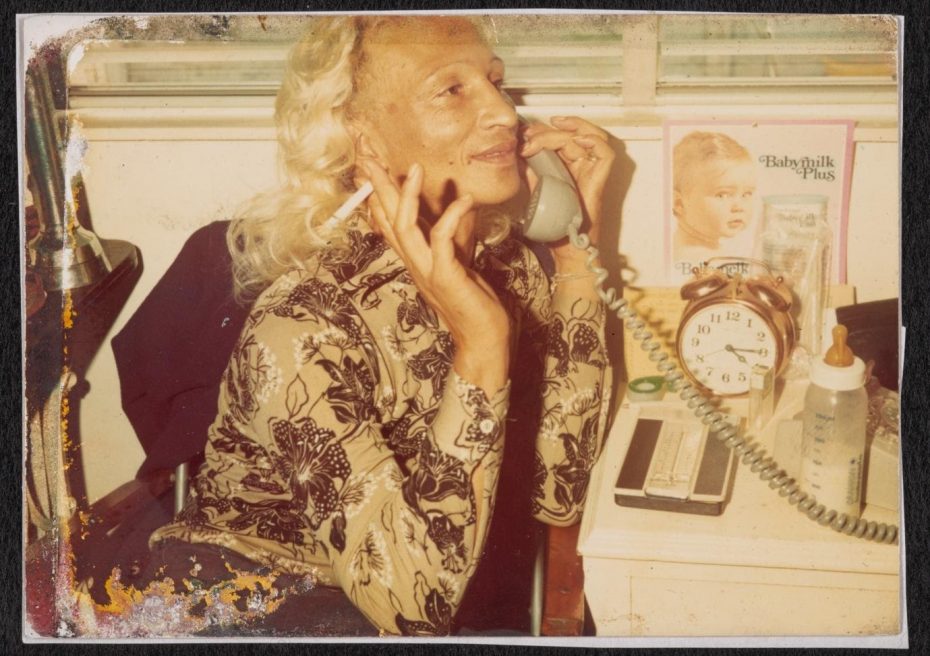

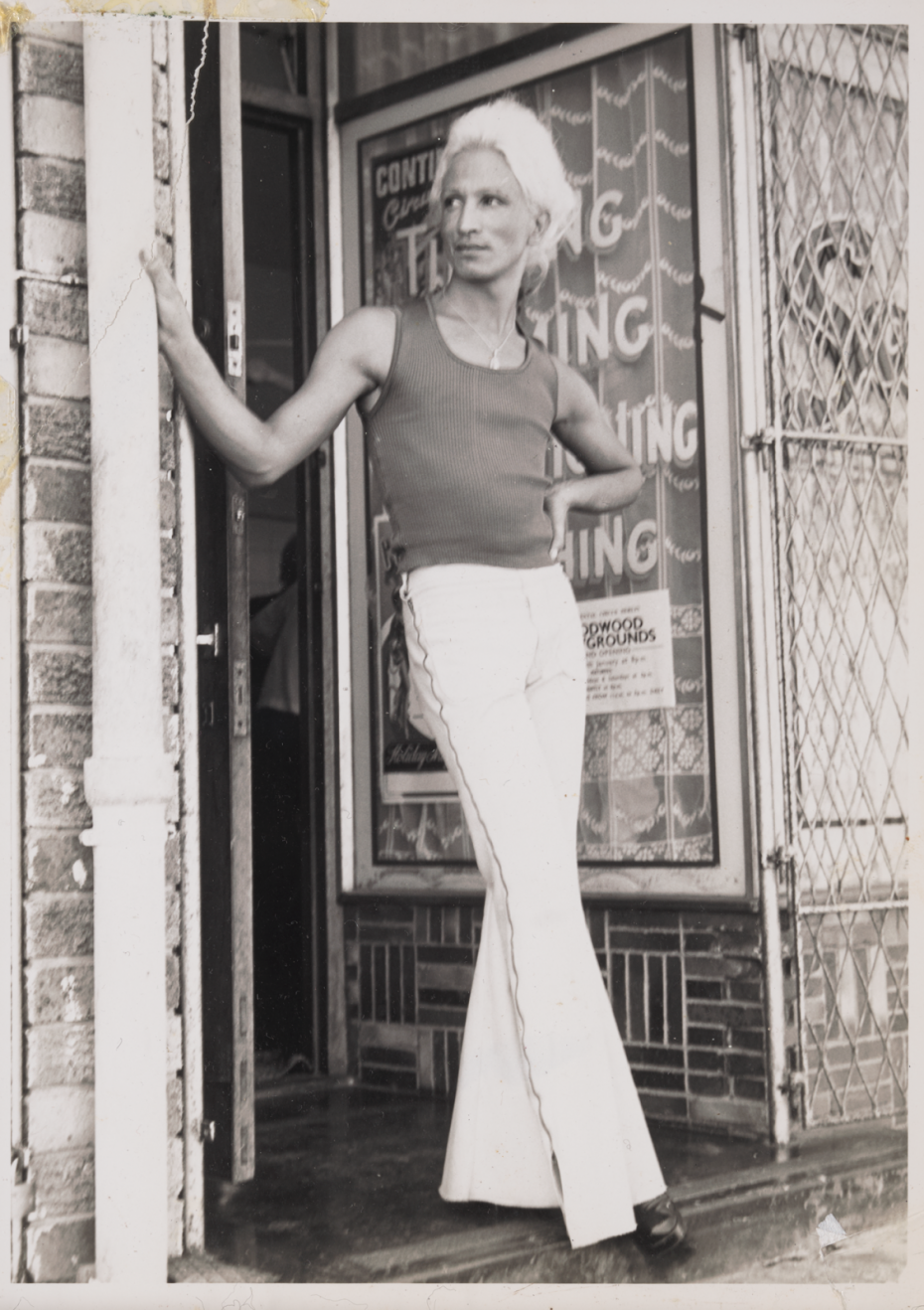

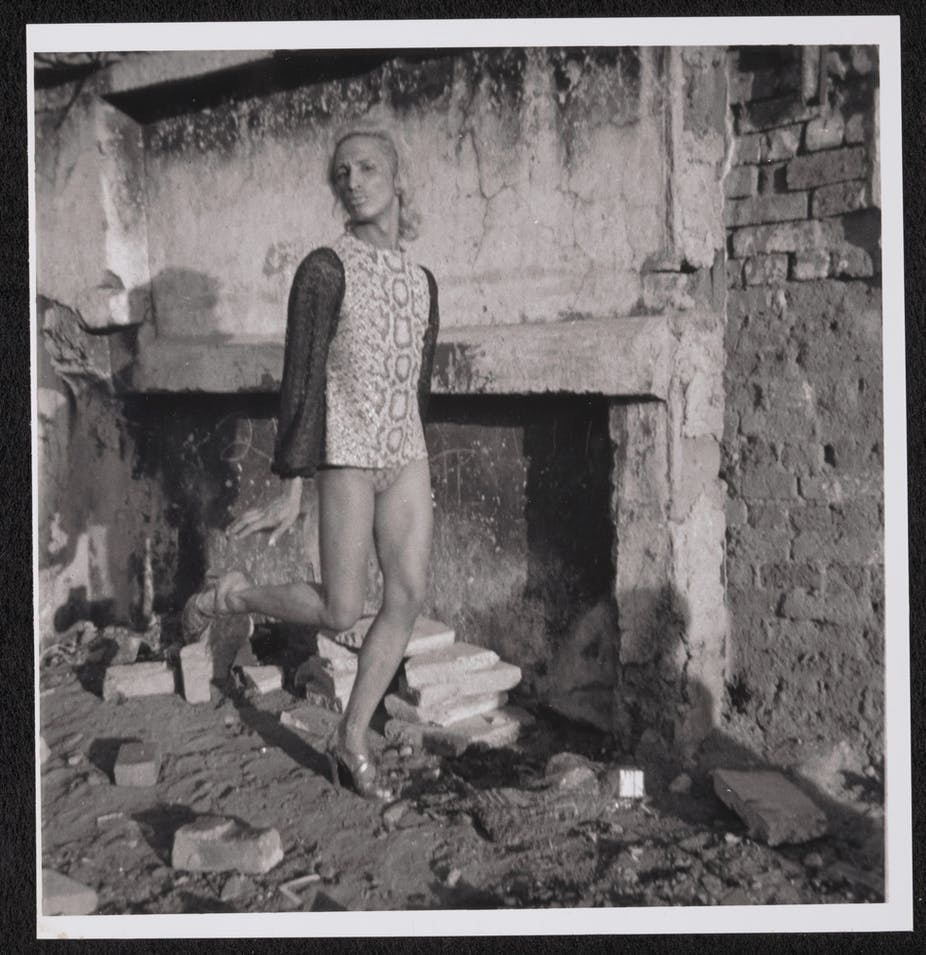

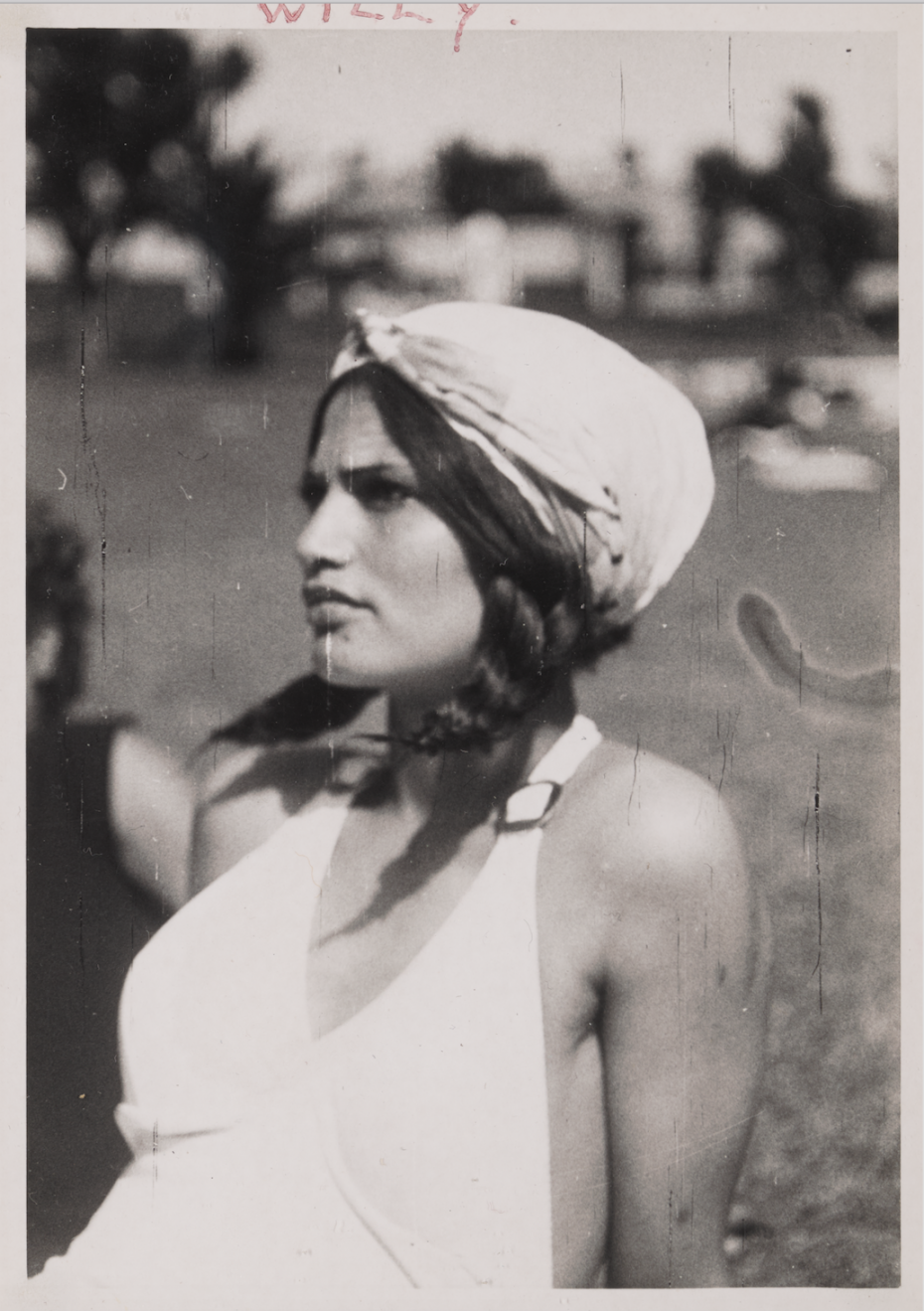

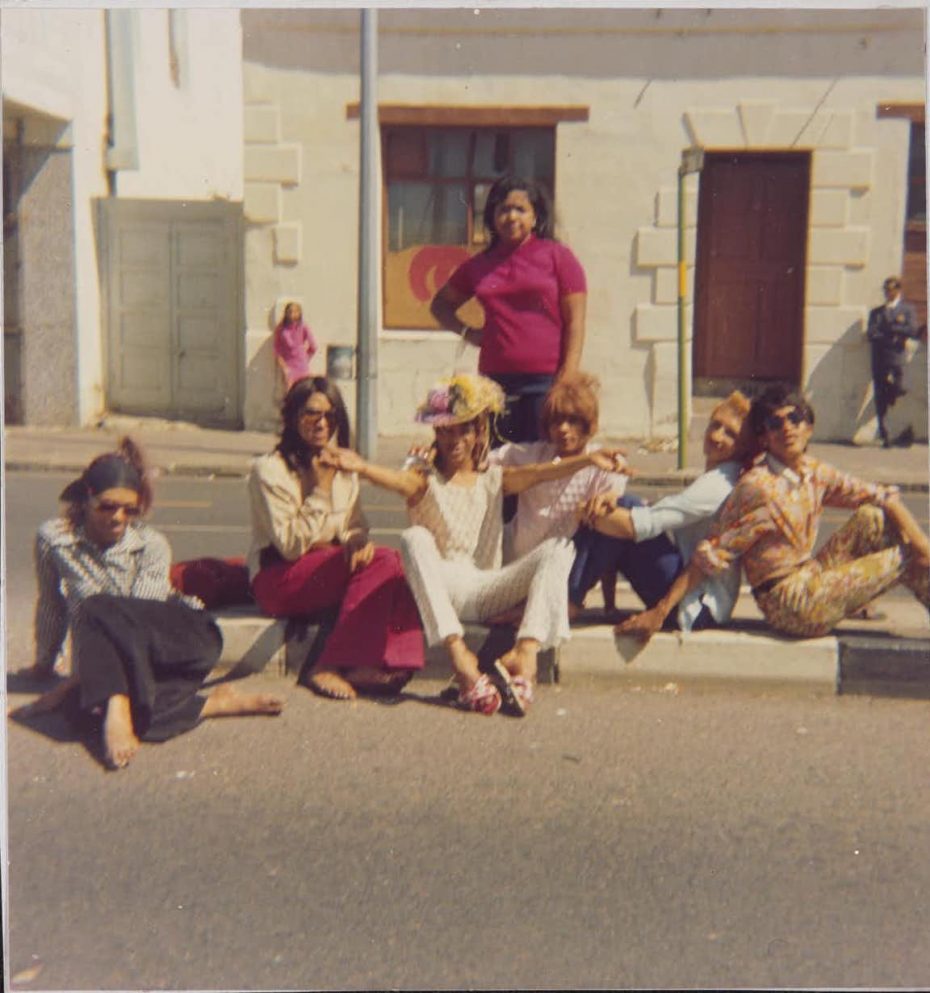

At this point in our journey it’s appropriate to introduce you to Kewpie (birth name Eugene Fritz, 1941 – 2012, also known as Capucine), a gender-fluid hairdresser to the stars, fellow drag queens and bohemians of District Six. Celebrated as the “daughter” of the community, she struck an arresting figure in her trademark beehive, stilettos and fishnet stockings. We can’t think of a better historic guide to take us through the scintillating streets and introduce us to the kaleidoscope of colourful inhabitants of District Six.

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

Kewpie kept an exhaustive archive of photographs that had been taken of her and her friends and personally labelled each and every snapshot. In 1999 she transferred her collection to Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA), a queer archive based in Johannesburg.

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

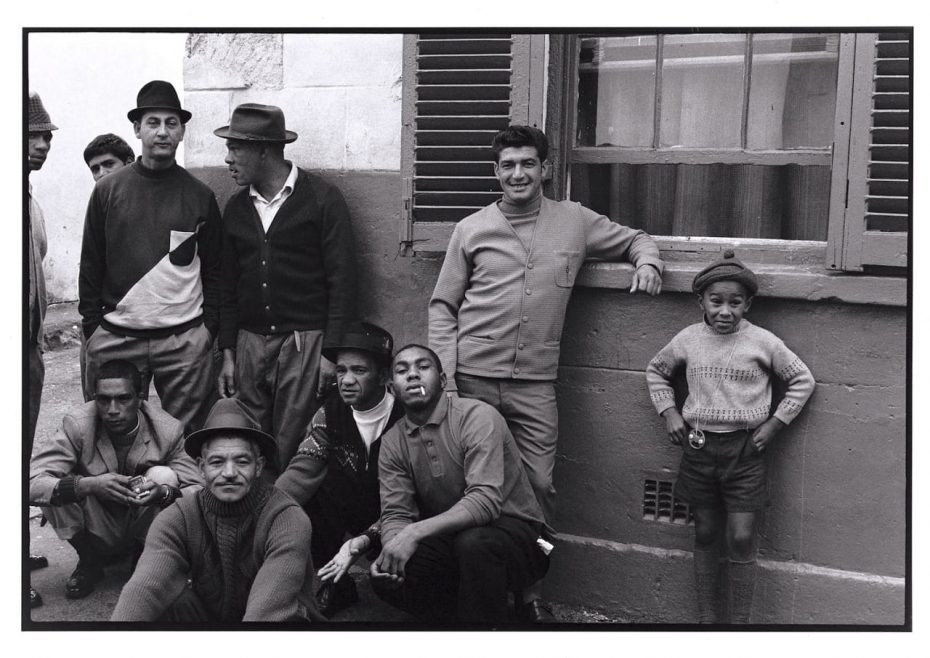

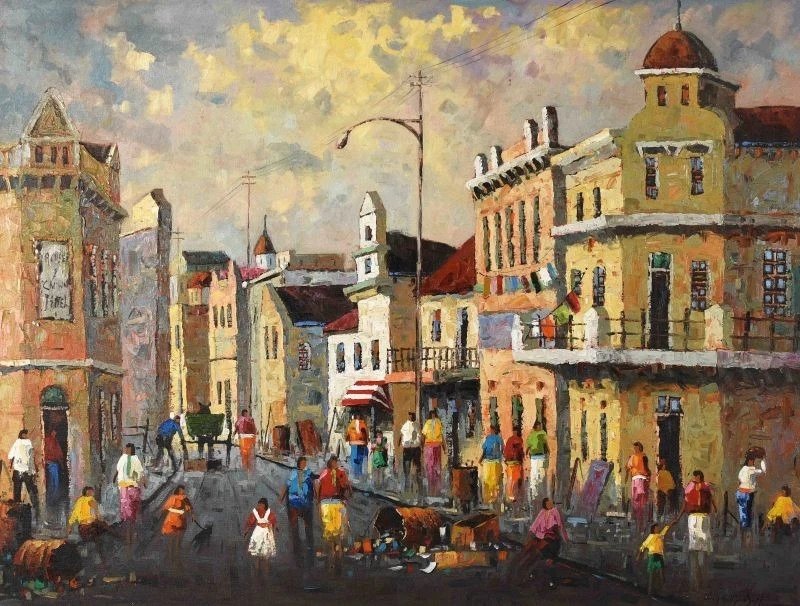

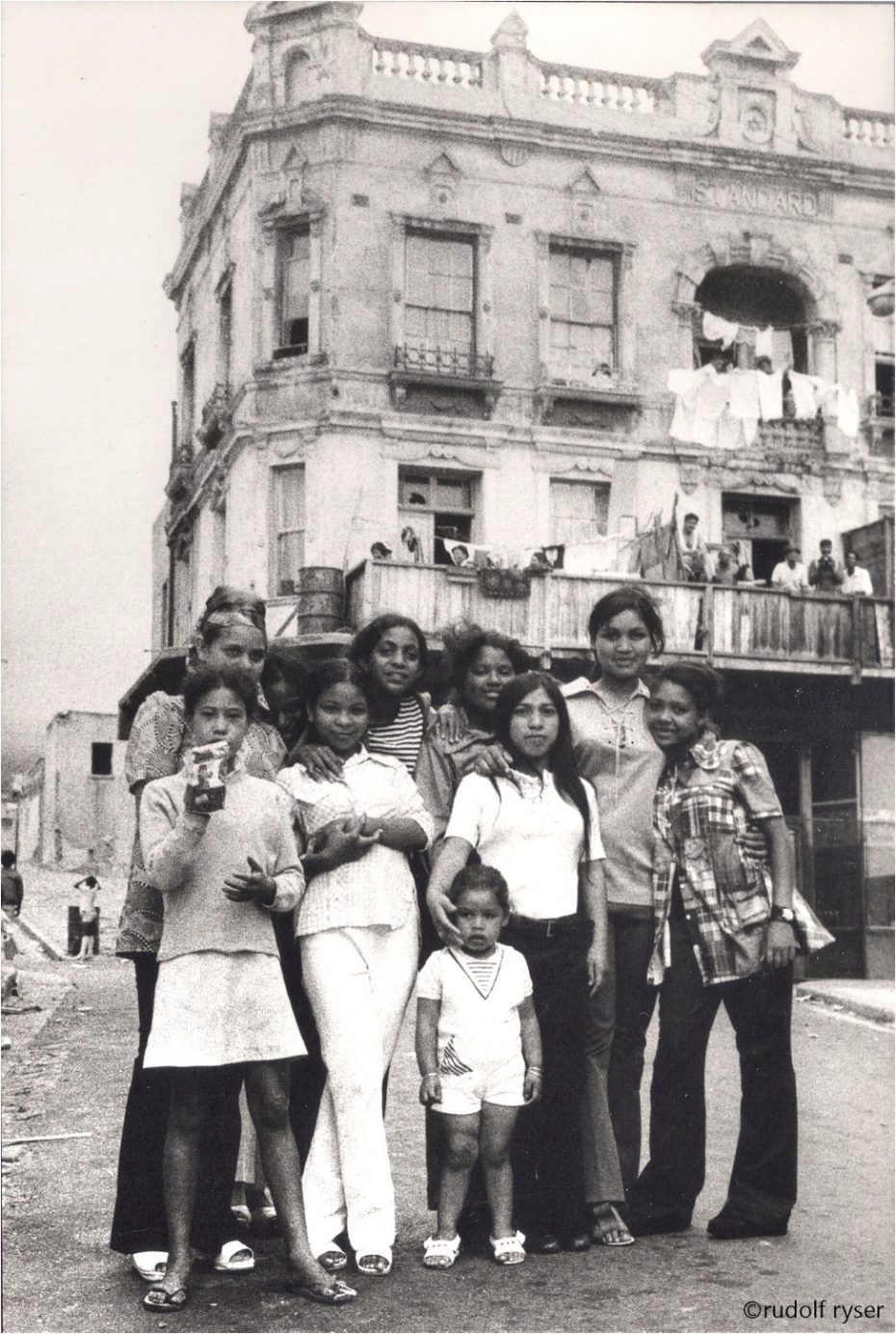

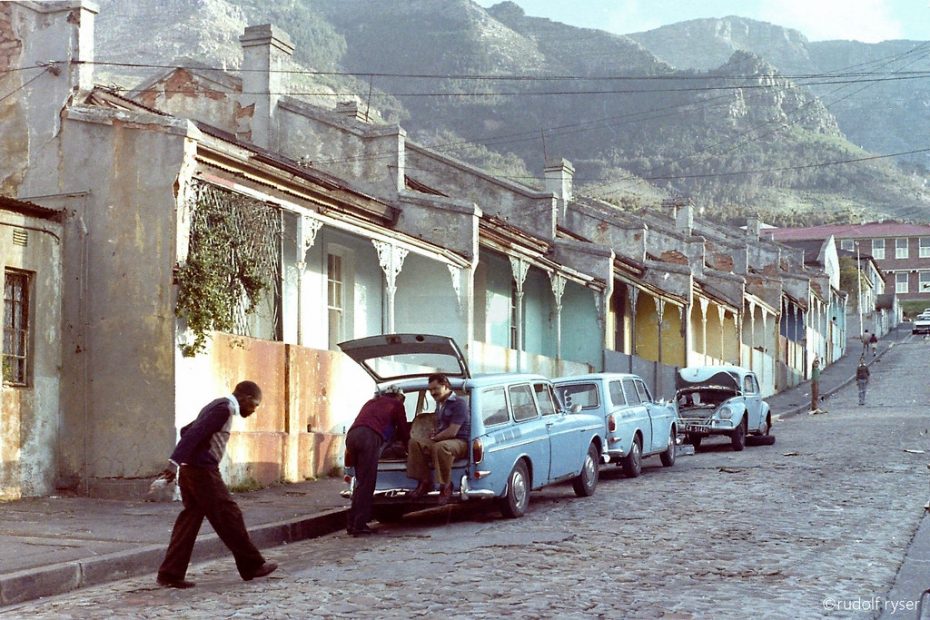

With Cape Town being a port city, sailors, soldiers and other globe-trotters found themselves drawn to this multicultural, if somewhat insalubrious, neighbourhood which culminated in a melting pot of fluid cultural influences, as one can well imagine. In the early days of District Six beginning around the 1860s, harpooners, soap-boilers, straw bonnet-makers, tinsmiths, bellhangers and candle makers mingled with fishermen, washerwomen, prostitutes and paupers who inhabited this place and co-existed harmoniously, all laying the foundations for the incessant hustle and bustle of this now legendary society.

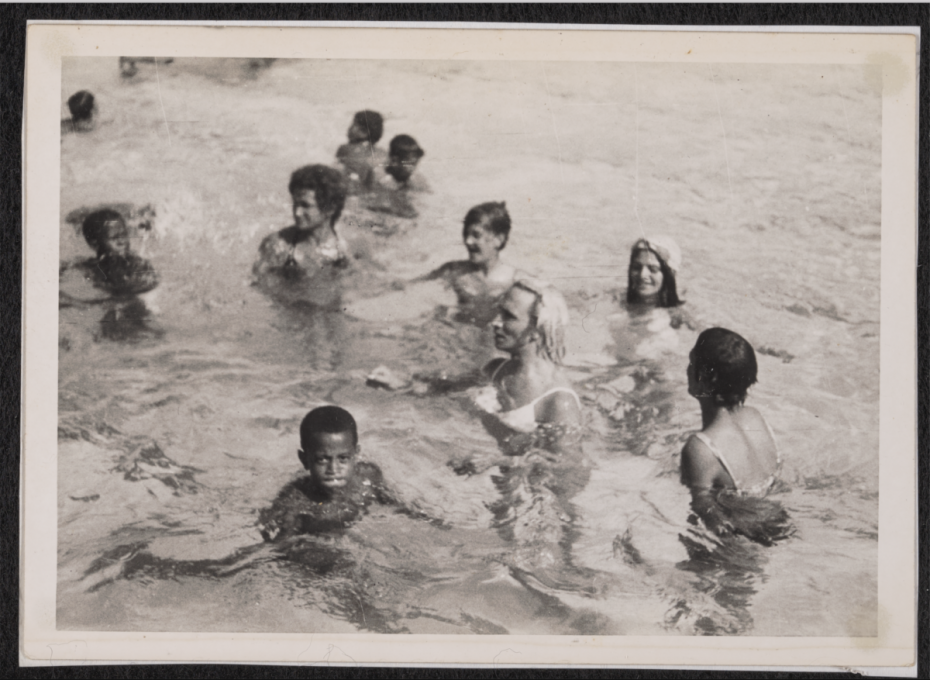

Jews, Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Malays (often political exiles from Java), ‘Coloureds’ (as they were referred to at the time), Africans, Indians and Whites lived in relative harmony, they mingled in a way that demonstrated how diversity was a strengthening factor, not an obstacle. Immigrants and freed slaves arrived to District Six, some stayed and some left after a brief stint in the neighbourhood. It was a transient, cosmopolitan community that kept evolving with history, each wave contributing to a new variety of influences, customs and peculiarities.

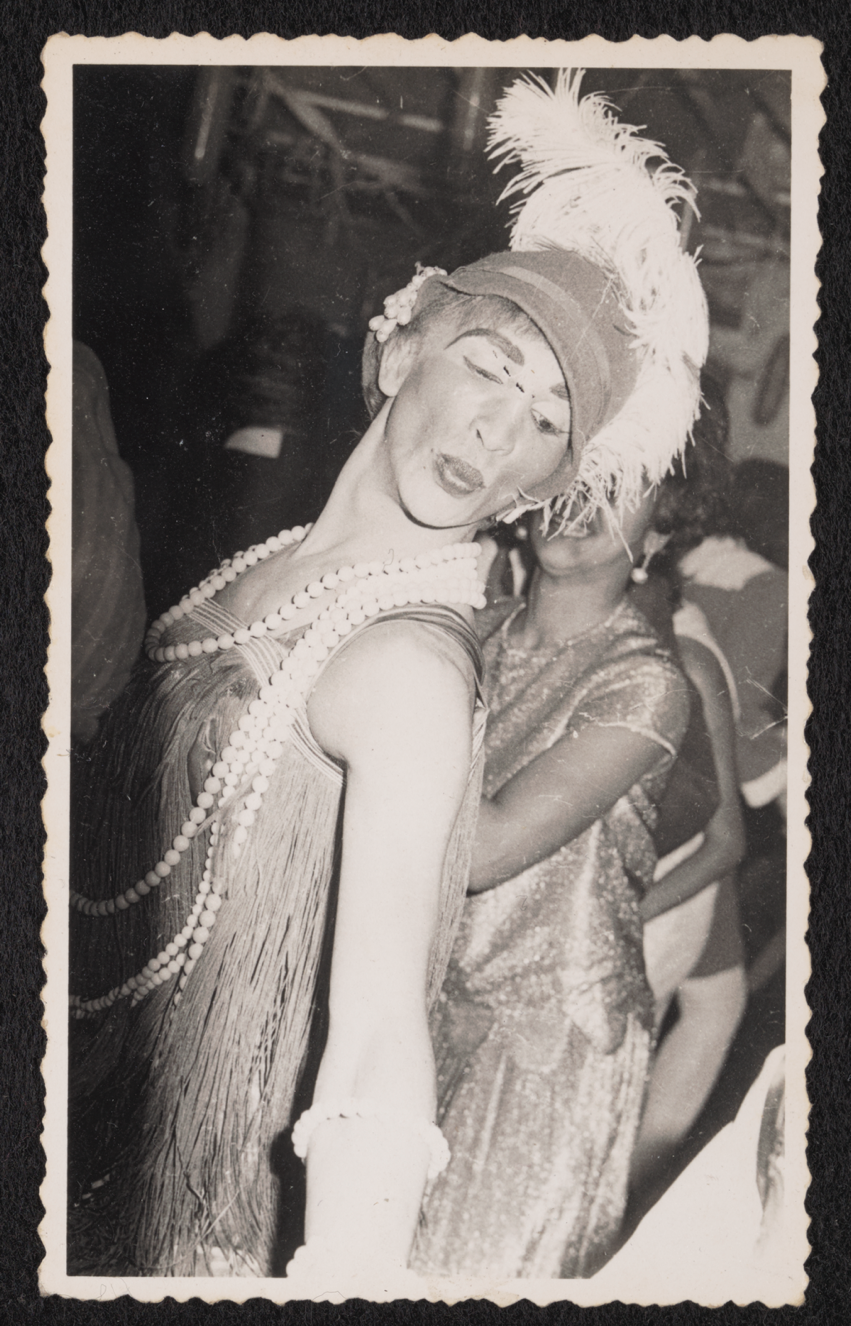

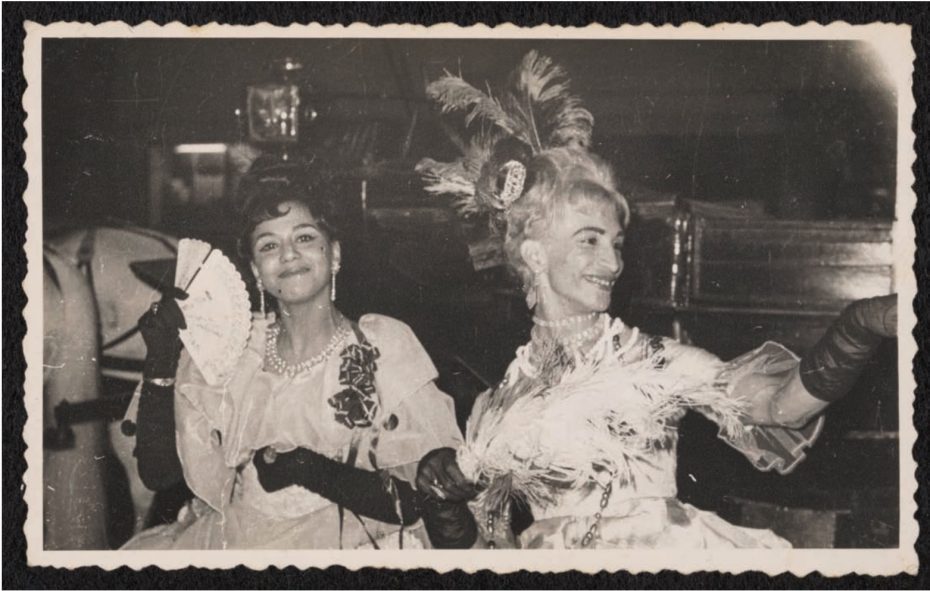

Social events were abundant in District Six. Extravagant beauty pageants, music concerts, all-inclusive street parties, cabaret and sensational fancy dress balls were at the order of the day. One such event was a Seventeenth Century-style Parisian ball hosted by the Ambassador Club on Sir Lowrie Road with our heroine dressed as Marie Antoinette, arriving at the ball in a horse-drawn carriage. According to Kewpie, “Driving through with these four horses and the carriage with my driver going along, and we had a traffic cop in the front and a traffic cop at the back. And at that time coming through the roads, the main roads, the bioscopes were coming out and people were going home. They forgot to go home … It was like a fanfare.”

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

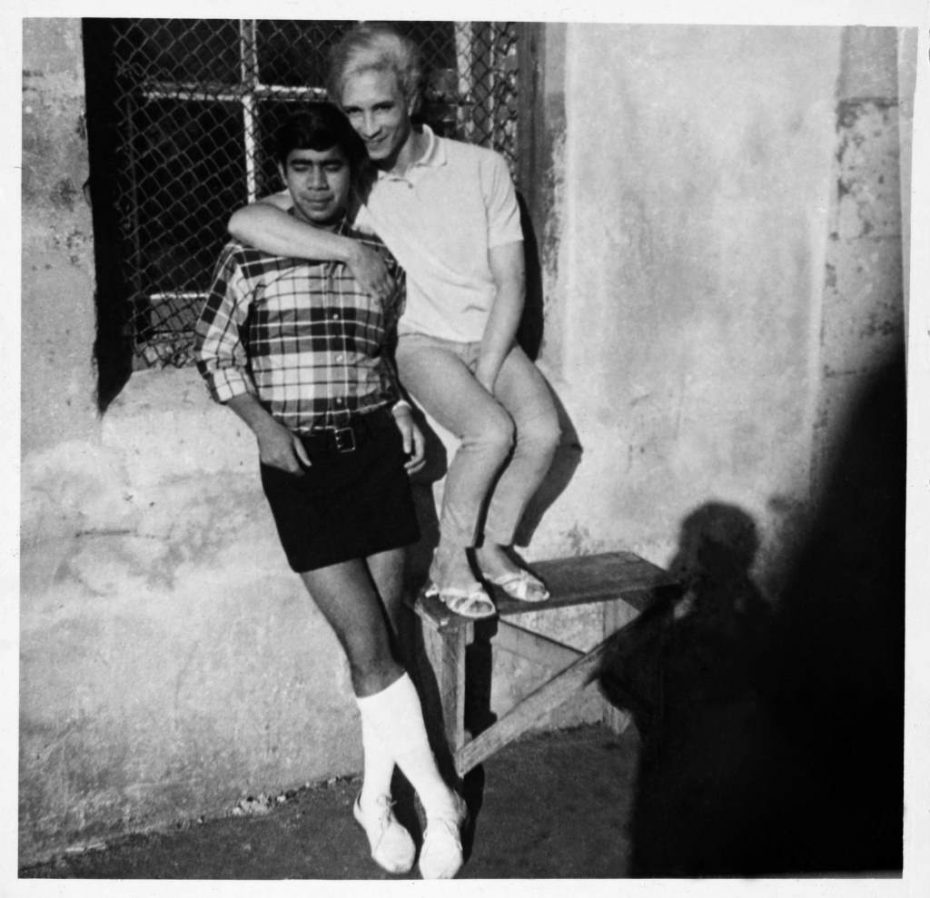

“At that time we weren’t called as gays, we were called as moffies then. But it was beautifully said, not abruptly,” recalled Kewpie in a 1997 documentary. The term can be highly offensive in today’s usage, but many members of Cape Town’s queer community were proud to called themselves “moffies” because it was more often used to identify talented entertainers and dancers and associated with the performance culture that developed in District Six. Mid-century Cape Town was more tolerant of the gay community than the rest of South Africa — encouraging gay men to flocke to the city from other regions.

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

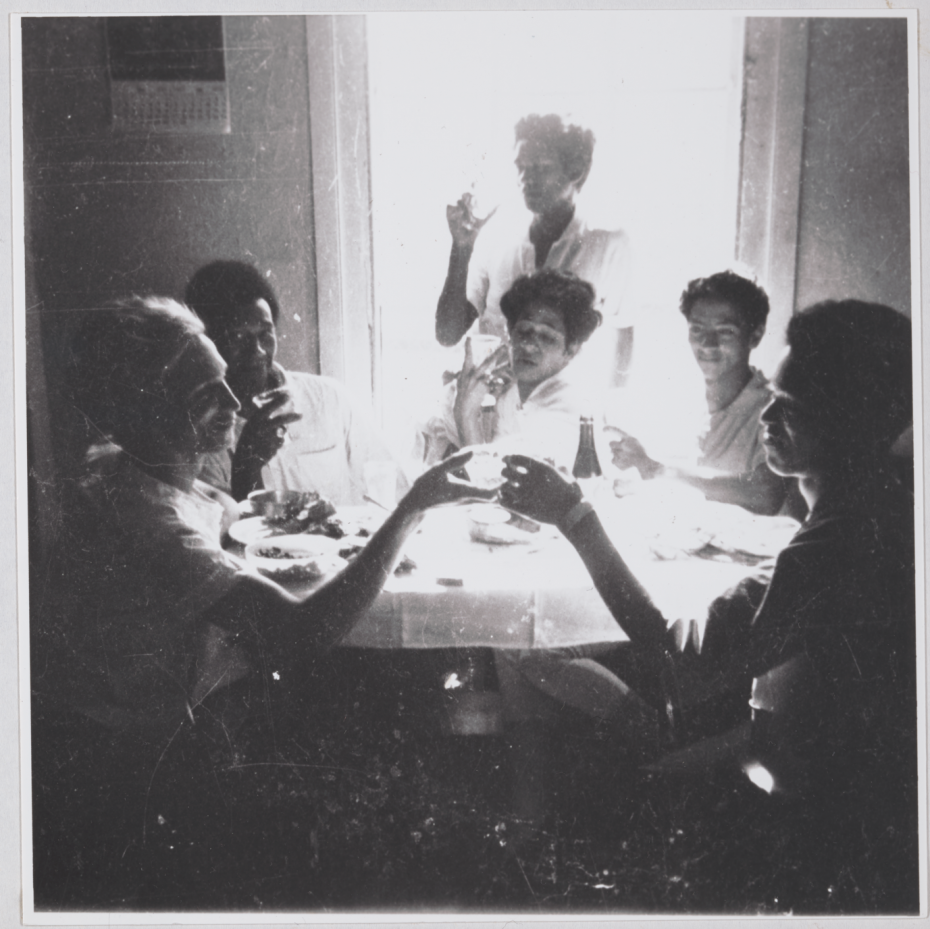

Their acceptance within wider society can be seen in Kewpie’s photographs. Appreciated not just as performers, but as friends, colleagues and family members, both in and out of drag. Kewpie and many other queer residents of District Six found homes within families headed by heterosexual couples where their gender and sexual identities were accepted. They played the role of daughters and sisters, providing childcare and domestic labor while parents were at work.

© Kewpie Collection, GALA Queer Archive, Johannesburg, South Africa

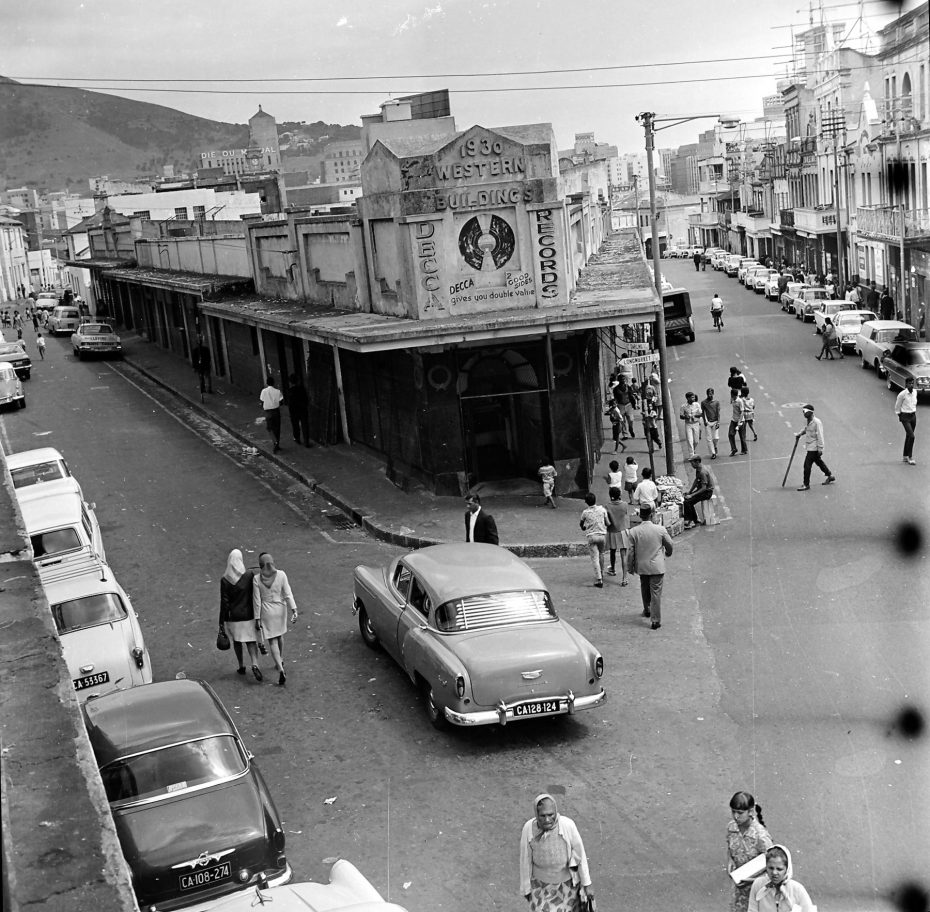

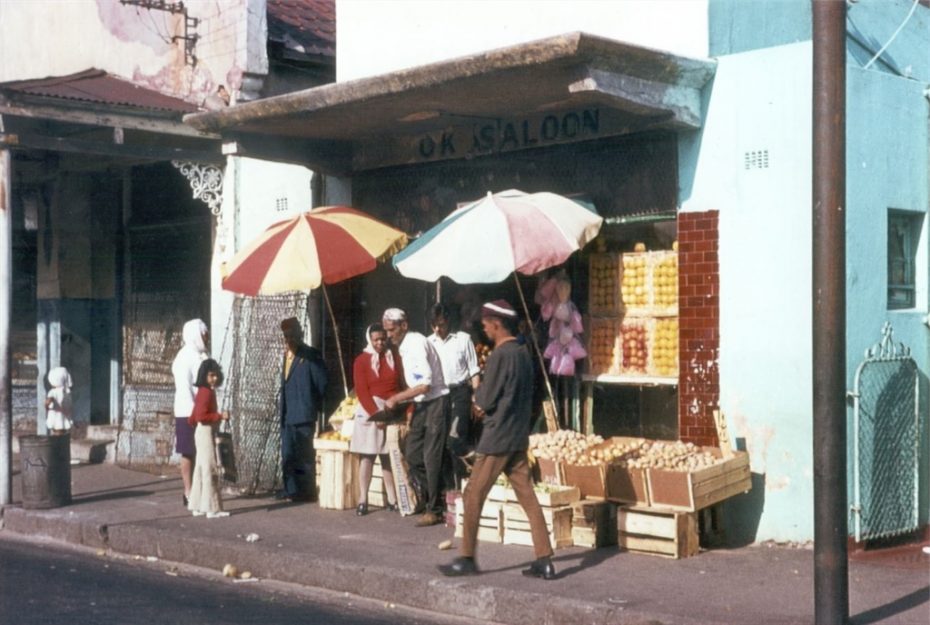

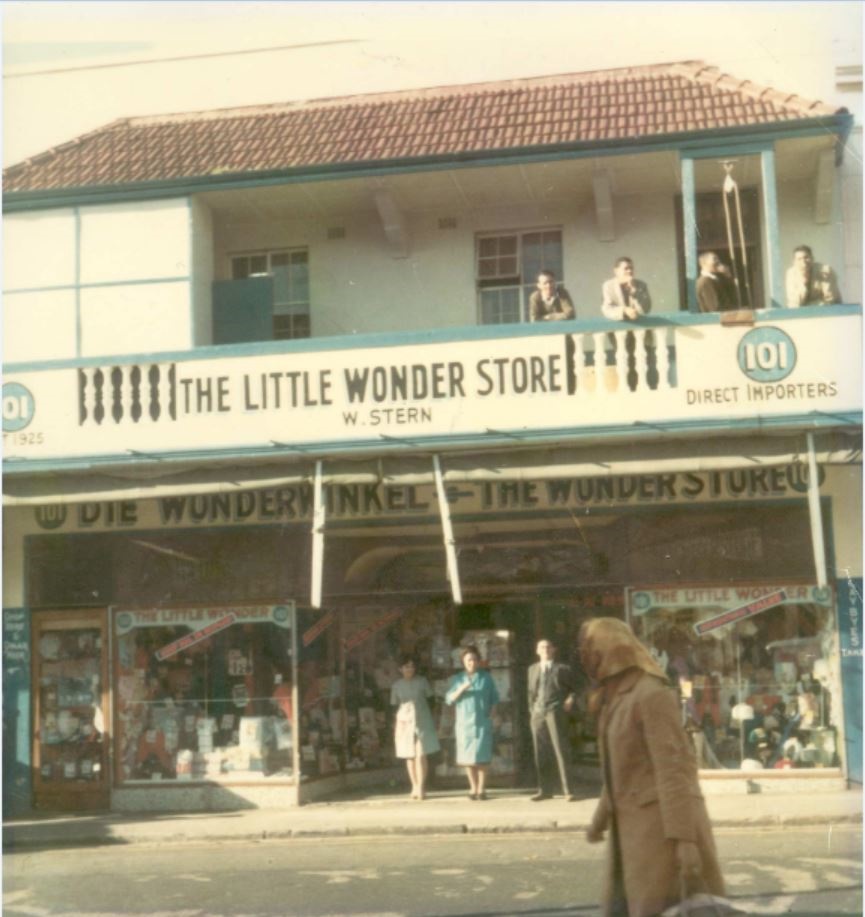

District Six, or “Distrik Ses” in Afrikaans, was as the name suggests the sixth municipal district of Cape Town and incidentally the only one that never got given a ‘real’ name. It was a well-functioning eco-system of ordinary folk going about their day-to-day business, working in the city during the day and ambling back from work at nights, stopping to chat to neighbours, past tenements, the many cinemas (District Six boasted four popular ‘bioscopes’), restaurants, photographic studios, flower shops and tailors.

They’d meander past vegetable vendors on the kerbsides, past herbalists offering bark and roots with unpronounceable names while the smell of spice hung heavy in the air. They may have been tempted to stop momentarily at one of the popular watering holes, with names more picturesque than the places themselves; The Cottage of Content and The Mount Pleasant. On special occasions they may have visited the marvelous Gaiety Theatre where ladies would be swishing silks and satins and their escorts dressed in dapped suits.

Alex Laguma, one of South Africa’s foremost activist writers and a former resident of District Six captures the essence of life in District Six with this quote:

From Castle Street to Sheppard Street, Hanover Street runs through the heart of District Six, and along it one can feel the pulse-beat of society. It is the main artery of the local world of haves and have-nots, the struggling and the idle, the weak and the strong. Its colour is in the bright enamel signs, the neon lights, the shop fronts, the littered gutters and draped washing. Pepsi Cola. Commando Cigarettes. Sale Now On. Its life blood is the hawkers bawling their wares above the blare of jazz from the music shops. “Aaatappels (Potatoes), ja. Uiwe (Onions), ja”, ragged youngsters leaping on and off the speeding trackless-trams with the agility of monkeys; harassed mothers getting in the groceries; shop assistants; the Durango Kids of 1956; and the knots of loungers under the balconies and in the doorways leading up to dim and mysterious rooms above the rows of shops and cafes.

Alex Laguma, ‘The Dead End Kids Of Hanover Street”, New Age, 2, No 47 (September 20, 1956),

It makes sense to hover a little longer around Hanover Street where Kewpie and her drag queen friends would hang out in spots like the exotic Crescent Restaurant, Star Bioscope and Zambezi Jazz Club. It’s clear that District Six provided a platform where bohemians, artists, musicians and other creatives of all races, religions and orientations could mix without inhibition and share ideas. This diversity on numerous levels – language, religion, class and origin – sadly represented the polar opposite of what the political regime at the time dictated.

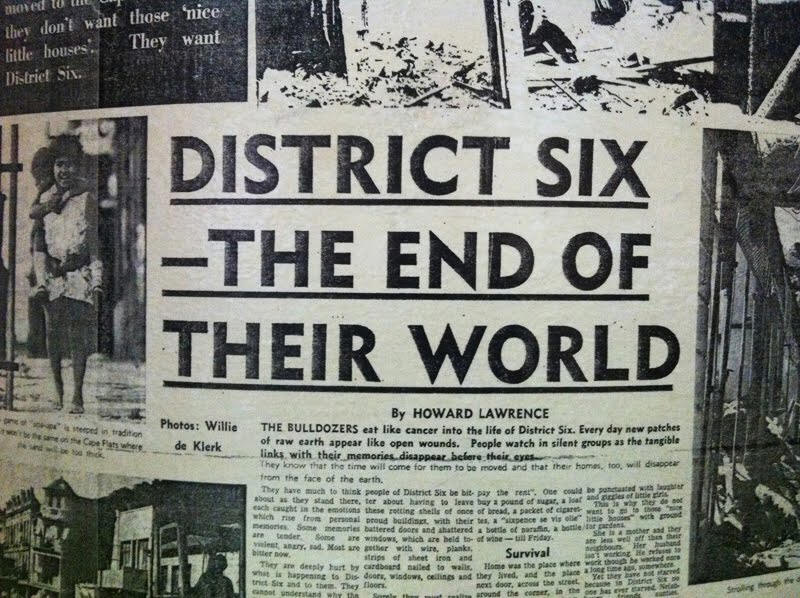

In 1966, District Six was declared a ‘Whites Only’ zone under the Group Areas Act of 1950 and by 1982 the plug was pulled. Community life was over for District Six. Over 60 000 people were forcibly removed to the outlying barren flatlands outside Cape Town (referred to as the Cape Flats) in what the government called a “slum clearing”. The area was eviscerated and dwellings, theatres and businesses bulldozed down. Only churches and Mosques were allowed to remain.

Ironically very few Whites moved in for fear over the outrage of what had happened. District Six became a symbol of apartheid oppression and to this day, is an undeveloped area and a reminder of an awful calamity in the history of South Africa.

The process of relocating families back to District Six is happening as we speak, but painfully slowly. Today the memory of this extraordinary slice of history of a cosmopolitan culture that once thrived, lives on in The District Six Museum, the gateway to the historic neighbourhood that lies between the city centre of Cape Town and artistic Woodstock.

It wraps around a strategic street corner as if keeping watch over the area. It’s an emotive and vibrant hub manned by those who survived, many now in their seventies and eighties, each with their own gripping story to tell.

If you care to listen, they recount with a twinkle in the eye tales of family intrigue and picnics, of illicit love affairs, potent masala curry and glamorous excursions to the beach. Unlike the water colour paintings on the interior of the museum that are steadily fading and dissolving with age, bleached by the sun through the windows, it seems to us the tales of District Six have unshakable staying power. In one way or another, by hook or by crook, this is one story that refuses to wane and it’ll live on in the psyche of a nation forever.