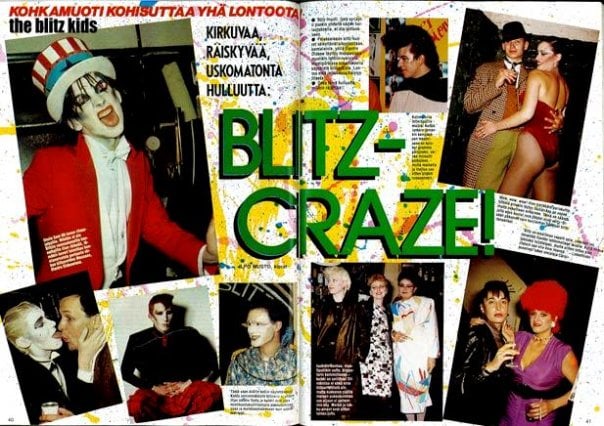

Sex, drugs and lots of black eyeliner. Just a regular Tuesday night at the Blitz Club. At the turn of the 1980s, London’s teenage squatters, outcast art school kids and disillusioned punks all descended on a barren Covent Garden in search of a good night out. By simply living out their wildest and wackiest fantasies, these gender-bending party animals changed the way we lived, looked, partied and played forever. Although London’s answer to Studio 54 only lasted a mere year and a half, the regulars, named the Blitz Kids by the press, birthed the New Romantic subcultural movement and set the style for the decade. Dressing up was an act of affirmation; no effort, no entry. Even Mick Jagger couldn’t make it past the Blitz bouncers. But stick with us, we can get you in, there’s some people you must meet…

Before we get to the fun bit, let me paint you a picture of 1970s Britain. Dreary, divided, and darn right depressing. There were constant strikes, Left and Right were battling it out, literally, in what was labelled the Winter of Discontent. Times were hard, prospects were grey, and the charts were as bland as anything. Soho had lost the swing that the mods brought in the 60s. Rumbling underground, a bunch of working class kids were determined to build their own Swinging London and escape into a colourful new counterculture.

Enter Steve Strange, proving that 19-year-olds can change the world. Most young Welsh lads moving to London from The Valleys would feel like a small fish in a big pond. But not Steve. He quickly made a name for himself as a nightclub promoter and became the leading painted face of London’s ubercool club kid scene.

In 1978, after mixing in the same circles, Steve Strange teamed up with future bandmate, DJ Rusty Egan, to run David Bowie themed nights in a seedy basement below a Soho brothel. A flock of too-cool-for-art-school teens who wanted to be ‘heroes just for one day’ commandeered the tiny club and quickly outgrew the space.

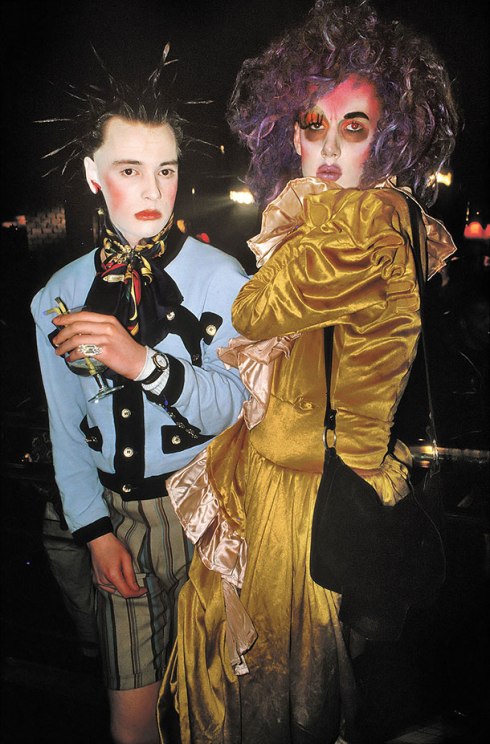

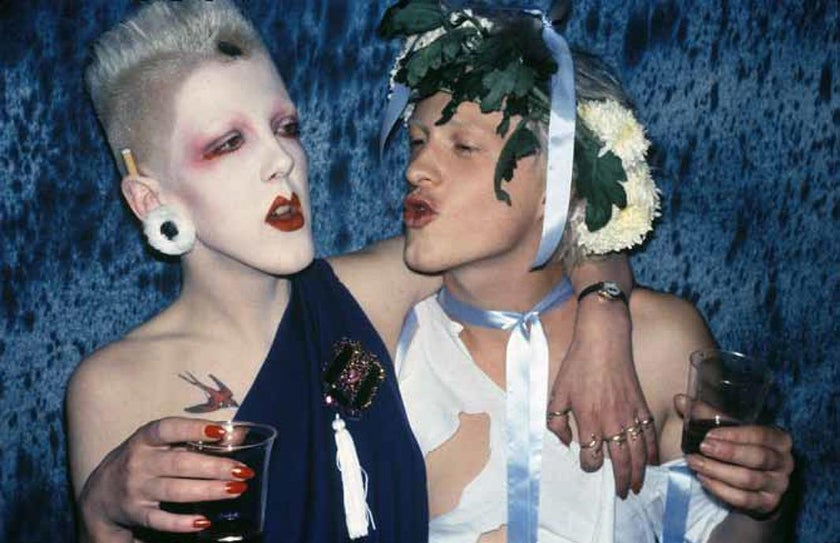

Princess Julia & Boy George

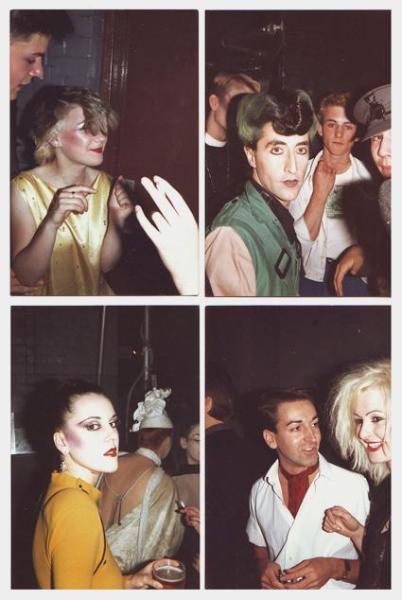

Martin Degville

An unpopular shabby wine bar in Covent Garden caught Rusty’s eye on his hunt for a new (cheap) venue to rent. Gingham tablecloths, framed pictures of Winston Churchill and dusty World War II memorabilia – just the place for avant-garde escapists to spend their Tuesday nights.

Despite being an image of 70s austerity in the stark light of day, by night, the Blitz became the home of an aspirational genderfluid future, evoking a more glamourous, European image of nostalgia. Think 1930s Berlin cabaret, with British accents.

Boy George ©

Paul McKay

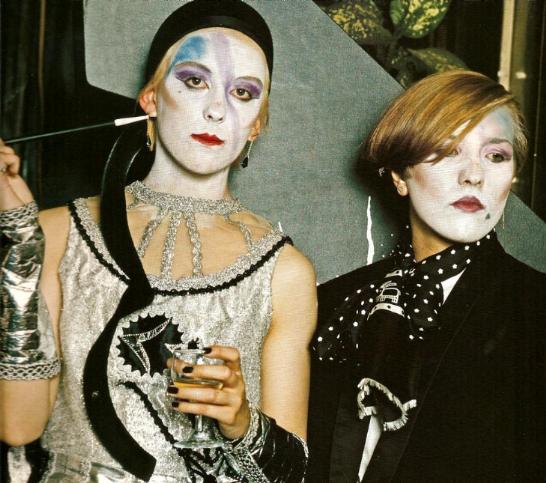

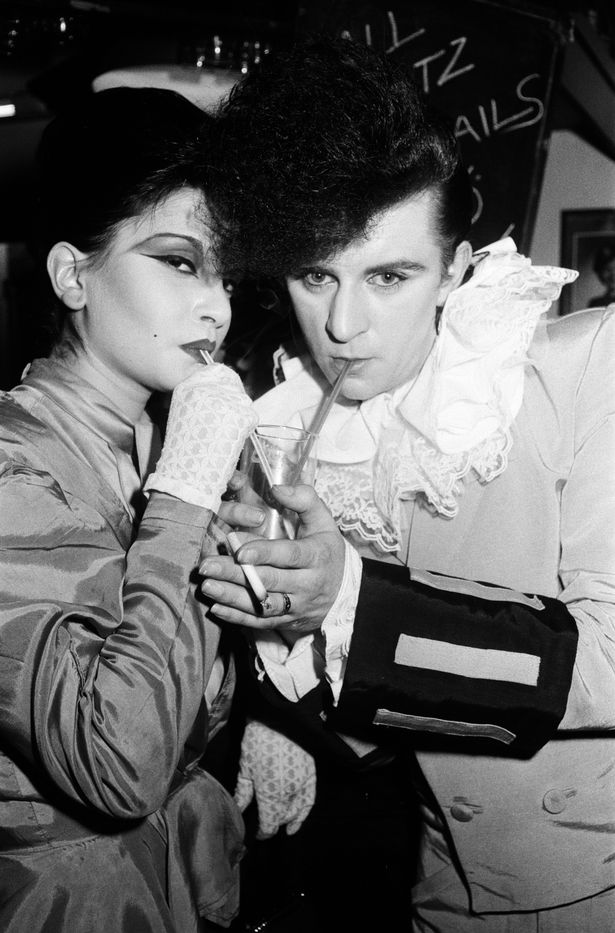

Blitz Kids © Derek Ridgers

Located smack bang in between two of London’s most important art colleges: the Central School and St Martins, the Blitz became the ultimate test bed for experimental androgynous fashion, later known as the ‘New Romantic’ look.

Unlike during the punk movement, traditional gender boundaries were pushed, and crossed. The guys wore more make up than the girls and dressed like movie stars with grubby fingernails. Living in a squat and being on the dole didn’t mean you couldn’t be glamourous. Flamboyant hairstyles, frilly shirts and film noir were all in. Penniless students lived like decadent divas. Everyone was so achingly fashionable, and they knew it.

© Sam Burcher

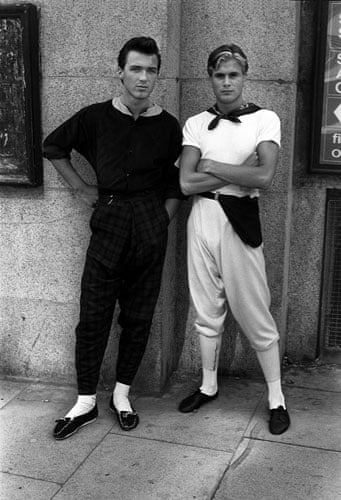

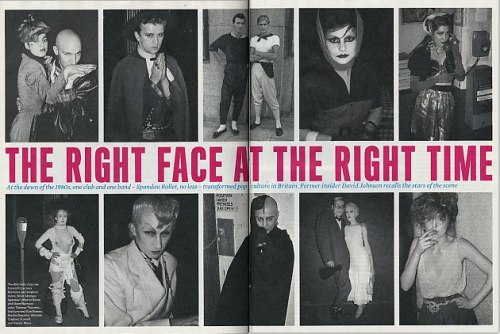

Spandau Ballet © Derek Ridgers

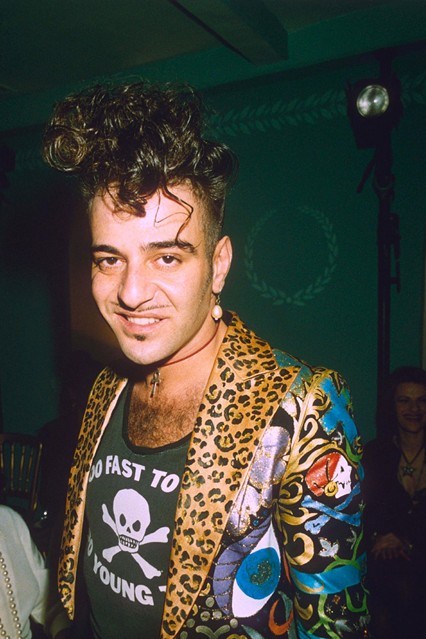

Young broke fashion designer John Galliano thrust himself into the scene, and his makeshift clubland couture eventually made it onto Dior runways where he was head of the iconic fashion house.

Another St Martins student on the scene was Stephen Jones, who lived in the same squat as Boy George. He was known for his pinstriped suit and stiletto heels combo, as well as creating competitions between his mates on who could take their look the furthest. Stephen designed outlandish hats for fellow Blitz Kids, his first clients, and is now considered one of the most influential and radical milliners of the 20th and 21st Century.

In the words of Steve Strange, the Blitz Kids, were a ‘burst of energy at a time when the London scene seemed so stagnant’. Pure punk had had its moment when the 1980s came a-calling. As well as a new look, a new sound was forged too, something more romantic, and robotic.

On the decks, Rusty embraced punk’s can-do, screw-you attitude, while pioneering softer synthy sounds, which he called ‘Elektro-Diskow’. ‘It was like stepping out of time’, says Midge Ure from new wave band Ultravox. Crowds of skint teenagers would dress up like glam rock 19th Century dandies and dance to futuristic tech-driven pop, like Kraftwerk.

These New Romantic rebels were London’s most modern thinkers. Brave and outrageous, punks from another planet.

Steve Strange and Rusty Egan took the soundtrack of Tuesday nights into their own hands and formed the synthpop band Visage. Their big hit ‘Fade to Grey’ was not only the anthem of the Blitz Club but also the first time the New Romantic style and sound reached the mainstream, topping the charts around Europe.

The lip sync superstar in the music video is influential Blitz Kid and London nightlife royalty, Princess Julia, who at the time was a hairdresser dossing on the same floor as Visage.

Vivienne Westwood usually steals the spotlight for her rebel aesthetic but Princess Julia, known to the cool kids as the ‘first lady of London’s fashion scene’, flies scandalously under the radar.

This muse du jour has been an IT girl not just as a New Romantic, but also in the punk scene beforehand, as a 90s raver and continues to champion queer underground art and drag in London’s East End today. Princess Julia has been out every night since 1976, and you can still find her partying at The Glory, a gay pub in Hackney, every Sunday.

Many of the Blitz Club regulars, who later went on to forge careers of their own and dominate the decade as cultural icons, used Tuesday nights to experiment, mingle and even make some money. Boy George worked on cloakroom duty. As well as his signature style, he was known for his kleptomaniac tendencies, often found riffling through handbags to top up his wages.

As well as Boy George, many big-name bands such as Spandau Ballet and Bananarama cut their teeth at the infamous clubnight. Record companies cottoned on to the growing popularity of Sinatra-style vocals over a synth and handed out record deals left, right and centre on the dancefloor.

Steve Strange played the role of gatekeeper as well as Gatsby. Word continued to spread of the hottest night in town, and so did his infamously ruthless door policy. You could spend all day painting your face and plaiting ribbons into your hair, just to get rejected by a 19-year old bouncer. Gutting. Some think Steve’s strange pleasure in turning people away was an elitist ego-trip, but as well as adding to the hype, it was a protective measure for the people inside, who were there to be their weird and wonderful selves. And a drunk denim-clad Mick Jagger was no exception to a stern eyeballing and a shake of the head.

One person who did make it beyond the doors of the Blitz was David Bowie. He turned up one Tuesday night in 1980 and whisked away 4 Blitz Kids, including Steve Strange, to star as extras in his ‘Ashes to Ashes’ music video. From the Bowie nights at the pre-Blitz basement to the Patron Saint of the New Romantics himself rocking up, Steve and Rusty’s work here was done.

After being blessed by Bowie, the press came to chronicle the scene with more interest, which got in the way of the fun. The New Romantic movement caught on like wildfire, while the original Blitz Kids who burned brightly then burned out. The bands who were birthed at the Blitz made it big, and once something becomes mainstream, according to the rulebook of cool, it loses its sheen. By 1981, the club where it all began was closed for good.

After the Blitz, Rusty and Steve moved around London setting up more clubnights and upping the scale each time. The days of putting on the Blitz were short but not always sweet. On the one hand, according to milliner Stephen Jones, it was a time when the queer community felt free, happy and ‘almost invincible’, in years before the AIDS epidemic hit.

However, as with many underground nightclub cultures, a image of excess combined with the availability of drugs doesn’t usually end well. Many came out rich and famous, as well as bruised and battered.

By daring to think, dress and dance differently, a queer clubland revolution was created from a rickety and rundown wine bar. A bunch of teenagers did the unthinkable and made punk glamourous, and in turn became cultural icons. International catwalks and magazine covers embraced New Romantic androgynous make up and fashion as the future. But most of all, as former Blitz Kid Christos Tolera remembers, what became of these short-lived Tuesday nights proved ‘working-class kids could really do something different’.

The British phrase ‘blitz spirit’ dates back to World War II, meaning ‘keep calm and carry on’ when everything around you is getting bombed to smithereens. In the 80s, when their future was crumbling around them, the Blitz Kids didn’t sit down, they dressed up. Slumming it in style and finding inspiration in the darkest and dingiest of dens, that’s the real ‘blitz spirit’.