You can tell a lot about William Boyce Thompson by walking through the magical garden he left behind nearly a hundred years ago. Meticulously sculpted and adorned with archaeological treasures at every turn, you’ll find sunken swimming pools lined with blue Roman mosaics next to a replica of what is thought to be the world’s first theatre, the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens; one brick wall is lined with an ornate façade taken from a sixteenth century Italian church.

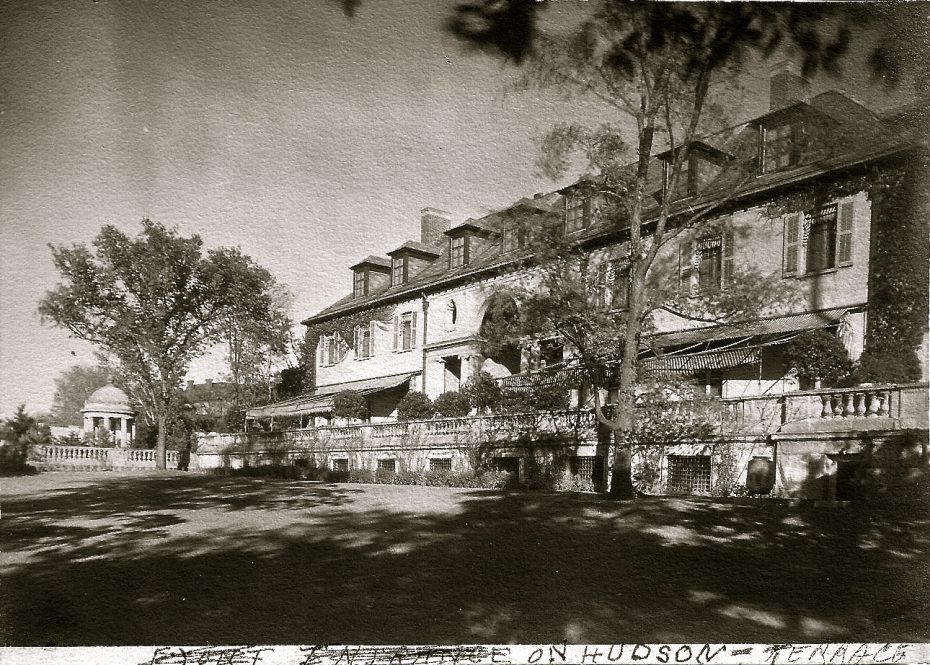

Lush, tree lined pathways pass crumbling brick walls, their alcoves decorated with classical statues. It is hard to believe that this secret walled garden, and the magnificent empty seventy-two room Renaissance Revival chateau it surrounds is hiding away in Yonkers, New York.

The Hudson River Valley was once peppered with other similar grand mansions; one nineteenth century wit commented that you couldn’t throw a stone in nearby Tarrytown, thirty miles north of Manhattan, without hitting a millionaire. Long before Long Island’s Gold Coast attracted the riches of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s era, the bluffs overlooking the Hudson River was the en vogue place for Manhattan’s elite to build their summer homes, shooting lodges and grand weekend estates.

The mansions of the Hudson Valley have suffered or enjoyed varying fates: some, like John D. Rockefeller’s expansive Kykuit, thrives as a tourist attraction; others, like John Bond Trevor’s grand Victorian Glenview mansion was cleverly appropriated into the Hudson River Museum. But others, such as lumber magnate Edward Joel Cornish’s estate outside Cold Spring, lie in ruins. Some were ravaged by fire, others, were sadly demolished. Walk through the woods and hills that line the Hudson Valley and you may stumble across overgrown foundation stones, staircases leading to nowhere, crumbling classical columns, even sunken swimming pools that tell you there was once a grand home here. But perhaps none are as magical as William Boyce Thompson’s Alder Manor.

A large part of the reason why Alder Manor is so captivating, is that it is enchantingly poised between being abandoned and perfectly preserved. The gilded paint is beginning to peel in some of the empty rooms, but the building has been well kept by current owners the Lela Goren Group. The walls may no longer be adorned with expensive oil paintings, and plush furnishings, but the grandeur of what Alder Manor once was is still there to see: and it has made the beautiful house the perfect backdrop for films such as The Royal Tenenbaums, Mona Lisa’s Smile, and A Beautiful Mind, as well as catalogue shoots for Victoria Secret.

The exterior is beautifully clad in limestone, with a Palladian Arcade giving onto a breathtaking balustrade terrace that runs the length of a house.

Step inside and you’ll find one room is decorated with a first rate English trompe l’oeil ceiling, another with a fifteenth century Italian stone fireplace. The central marble staircase would be impressive enough even without the Wetle Philharmonic Organ, whose grand pipes give the staircase the air of a modest cathedral.

“The most dynamic ‘room’ may be the foyer,” explains Boyce Thompson, about his great uncle’s house. He writes an entertaining website about his illustrious ancestor’s history. . “It is easy to imagine dozens of well-heeled guests sipping champagne there, with waiters carry hors d’oeuvre trays. Someone could make a grand entrance down the stairway.” Or else there was a poker room in the basement, which the New York Times once described as an ‘Old West gambling den,’ and to which William Boyce Thompson invited the estate workmen. “He would play cards with anyone, regardless of rank”.

Walk down the empty corridors and you’ll discover enchanting secrets behind the doors: one leads to an exquisite gentleman’s library room, the floor to ceiling bookshelves still lined with leather bound books, some of the only human touches still left in the mansion. One room contains a secret safe, sadly empty.

Another door on the second floor leads to something even more remarkable – a luxurious marble lined indoor plunge pool. The engineering work alone to install such luxury in the middle of the house must have been immense, to say nothing of the cost. “The pool was a flight of folly,” remarks Boyce Thompson. “It would have been much easier to put on the first floor!”

The level of opulence shouldn’t come as a surprise given the architects: for if you were to build a grand mansion, you could do no worse that hire Carrère & Hastings, the firm who built the main branch of the New York Public Library, the United States Senate Office Building and the Frick Mansion on the Upper West Side.

But William Boyce Thompson was no ordinary millionaire. Born in the far less glamorous surroundings of Alder Gulch, Montana in 1869 – the small town would inspire the name of his mansion – Thompson worked in the mining industry, eventually striking untold riches with the Magma Mine in Superior, Arizona. His mining company, the Newmont Mining Corporation swiftly became one of the largest producers of copper in the world, and is still mining gold, silver and copper today.

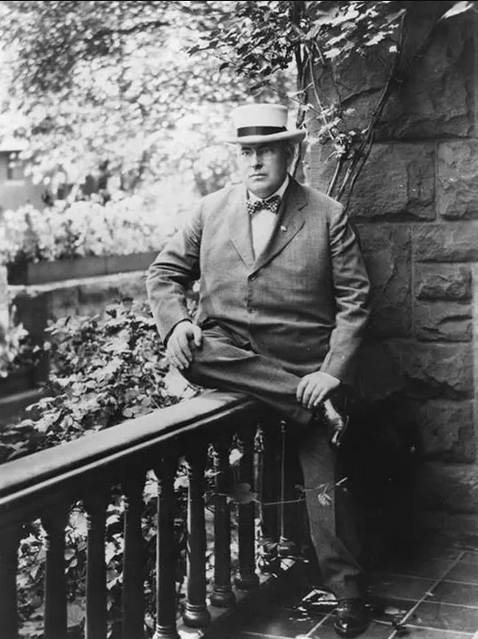

Often called simply, ‘The Magnate,’ Thompson indulged in other pursuits with his new found riches: he became involved with Indian Motorcycles, the Wright-Martin Aeroplane Company, and he owned his own private Pullman Car, which since 1971, disappeared somewhere in the national railway system of Mexico. But William Boyce Thompson would become more well known for his philanthropic work. The few remaining photographs of Thompson show him not to have the hard face of a robber baron, but a jovial, avuncular appearance. “He worked like the devil,” maintains his great nephew. “Sometimes through the night, and ate big meals on trains…he once consumed two welsh rarebits before embarking on an overnight train to Boston, and topped out at more than 300 pounds. Interestingly, his weight gain corresponded closely with his gain in wealth!”

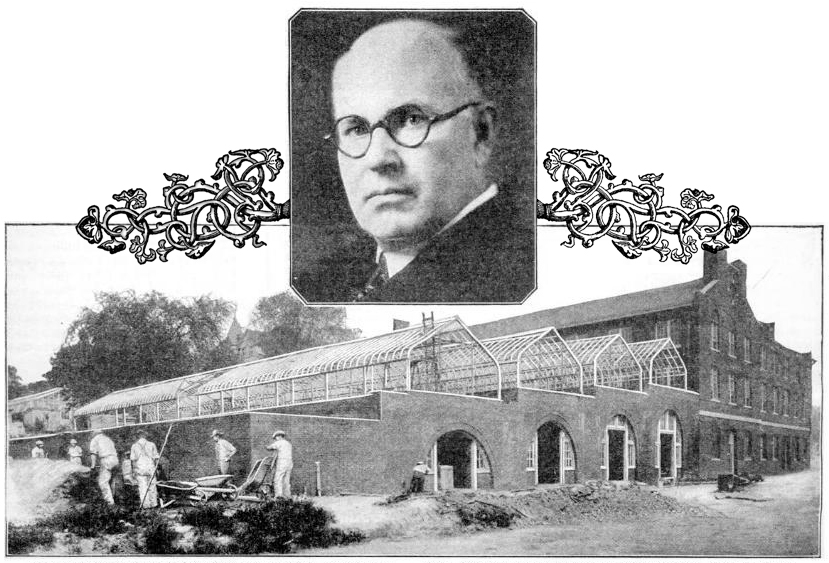

In 1917, Thompson visited Russia just after the Revolution had started. He was struck by the poverty and starvation he saw, and his work for the American Red Cross mission would see him awarded the honorary rank of Colonel. Returning to America, W.B. Thompson resolved to help the pressing need for food, and across the road from Alder Manor, he built something most unusual: the William Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research.

The Boyce Thompson Institute opened in 1920 at a cost of $10 million, as a state of the art laboratory to alter genomes, cross pollinating experiments and other attempts to man make vast quantities of food stuffs. Their mission : “why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered.”

But the altruistic experiments began to be affected by the growing urban pollution coming from Yonkers down the road, and the Boyce Thompson Institute left their home, relocating to the Cornell Campus, where they still exist today as an independent research facility, leading the way on tomato genome experiments amongst others.

Like Alder Manor, the Boyce Thompson Institute lay abandoned for years, becoming a legendary expedition for urban explorers, who sought out its peculiar decaying scientific laboratories and rows of overgrown greenhouses and rusting plant research equipment. The Institute was recently developed into a modern office complex, but the Manor House has retained its old world charm.

William Boyce Thompson died in 1930, leaving an endowment for his wife to live in Alder Manor until her own death in 1950. His grand home became a Catholic school for a while, then a home for an Irish Fraternal organisation, but for years later, it stood unused. Alder Manor may have suffered the same fate as many of the torn down mansions of the Hudson River Valley, until it was bought and preserved by the Lela Goren Group, a property developing company with the eye for the esoteric. “I guess you could say that I’m attracted to magical spaces” explains Lela Goren, whose mission is to “find and reveal overlooked potential, and envision new chapters for buildings full of stories and rich with history.”

A few miles from Alder Manor, a hulking abandoned power plant dominates the Hudson River edge. Built in 1907, it is one of the only remaining plants built to electrify the Grand Central Railroad out of New York. Abandoned in the 1970s, it became a notorious gang hideout, earning the ominous local name, the ‘Gates of Hell’.

Like Alder Manor, the old power plant was saved by Lela Goren, with plans for the structure to be reimagined as a space for events, workshops, public art and gatherings that engage entrepreneurs, innovators, scientists, artists, youth and governments engaged with climate solutions.

Saving both properties is a giant undertaking. Joan Vogt works as the film and photo lead for the Group, starting as caretaker at Alder Manor almost twenty years ago. “The Manor is huge and was neglected for many years,” she says. “The cumulative effects of unstable heating and cooling is really what starts to cause decay….It is a labour of love. The greatest thing about the current owner is her commitment to preservation. The first day I met with the team, I wanted to cry with relief. They are doing it right, and that means that they have been focused on the roof preservation since day one.”

When William Boyce Thompson still lived in Alder Manor, the home was filled with treasures. The front hall contained Italian Renaissance chests, Ming Dynasty vases three feet wide, and terracotta reliefs from fifteenth century Florence. “During Thompson’s time, the home contained a wide variety of murals, chandeliers, stained glass, sculptures, and other art treasures,” explains Boyce Thompson of his ancestor. “The family no doubt removed some furnishings and art before the building was willed to the Archdioceses. But many items remained until the church sold them at auction in October 1995.”

The few surviving period photographs show a ‘minerals’ room in the basement, that was copied from rooms in the Imperial Palace in Beijing, filled with precious stones, minerals and carvings.

Thompson would leave his unparalleled collection of over 1,500 mineral specimens and carvings to the American Museum of Natural History, as well as an endowment of over $50,000 to buy other outstanding gems and minerals, such as a 596 pound topaz crystal from Brazil.

“The best thing about the manor is the history is still being uncovered,” explains Vogt. “There is so much to learn. Just the other day we were talking about limestone, how and where it came from, the local quarries, etc. We know about the famous architects (Carrère and Hastings) and the owner, but the history of the craftspeople and the materials are largely still a mystery. Alder has a distinct personality. I feel like I’m in a relationship with building.”

Today the Hudson River Valley is a captivating place to explore. Whilst some of the old millionaires’ mansions have crumbled into the forests, and others have been preserved. Alder Manor remains poised between the two.

Walking through the gentleman’s library, still lined with books and perfectly preserved, it feels as though the miner from Montana-turned great copper Magnate had just stepped outside to admire the archaeological treasures of his walled off garden. When the home later became a Catholic school one of the residents once remarked that William Boyce Thompson’s mansion “reflects the complex personality of the man who, although he came out of a rough background, still wanted to exhibit beauty and grace.”