In HBO’s hit series, The Flight Attendant, actress Kaley Cuoco does a sterling job of portraying how many of us would typically draw a flight attendant if we were asked to. Slim build, check. Perfectly highlighted blonde hair swept immaculately into a chignon, check. Carefully applied makeup, check. Caucasian woman, check. As we catapult through the air in a metal tube, we know that flight attendants are there primarily for our safety, but if we’ve tackled sexism in the skies, why can’t we do the same for the lack of racial diversity?

Much like the fashion and film industry among others, the aviation industry has long struggled to recruit women, people of colour and members of other marginalized groups. According to one news study, across the American aviation industry only 10% of those working in it are Black, Asian, Hispanic, or Latino Americans. But there are those who have fought against the grain, pushing to get more diversity into the industry. Unsurprisingly they have been met with challenges and as we can still attest to, there is a still a long way to go…

One woman who made waves was Léopoldine Doualla-Bella Smith, who is recognised as the first Black flight attendant. Léopoldine was born into the Cameroonian royal family, back when Cameroon was still a French colony. The young princess had other ideas about how her life was going to go, and on seeing an offer for a ground hostess position, she took on the job which she carried out after school. In 1956, when Léopoldine graduated from her high school at the age of 17, she was recruited to become a fully-fledged air hostess and sent to Paris to train with Air France, later joining the Union de Transports Aériens (UTA) and then in 1960 Air Africa, an airline owned by West African countries which was created to serve 11 of the now independent French-speaking African nations.

Léopoldine throughout all of this, was making history. Not only had she become the first ever Black flight attendant but as an African with experience in French aviation, she became the first official hire for Air Africa. Her employee ID card simply read, “employee no.001”.

While Léopoldine’s career in the skies was soaring, down on planet earth, race relations were not progressing at quite the same speed. As she flew across the world, once she touched down, she was often subjected to deplorable discrimination. In South Africa, whilst apartheid had literally torn the country in two, Léopoldine was prevented from leaving the plane with her fellow stewards and was instead covered and chaperoned into a separate, hidden accommodation.

In America, race relations also raged through the country and the late 50s and early 60s saw the civil rights movement take hold of the country as marches, protests and demonstrations sought to end the segregation, slavery and discrimination that African-Americans had for so many years been subjected to. This impacted the way Léopoldine was treated on board her flights, as passengers unaccustomed to seeing a Black flight attendant, treated her with little respect. Of this time Léopoldine recounted how, “Some people were just rude. They would tell me, ‘Don’t touch me and don’t touch my child.’ They would say, ‘I don’t need you to do anything for me.’ I would grant them their wish and just walk away. If I reacted any other way, I would be racist myself. You could get mad and bitter or just move on.”

Léopoldine had shaken things up as the first black flight attendant and was followed shortly afterwards by the first Black American flight attendant, Ruth Carol Taylor in 1958. For Black pilots however, getting to the cockpit was proving even more of a struggle. In 1957, after serving as an Air Force Pilot, Marlon Green decided to apply to a number of passenger airlines for the position of pilot. After numerous applications received no response, Green decided to leave the race box unticked on his application to Continental Airlines and not include a picture of himself.

This move got Green to the final round of interviews, as he went up against four, all white, pilots who each had significantly less experience than himself in the air. All four of these pilots were hired by Continental and Green found himself once again rejected from a pilot’s job. This time around Green was not content to sit back and do nothing and instead mounted a court case against Continental Airlines, a case that would take six years to finally come back in Green’s favour. Continental were ordered to enrol Green in their pilot training programme and retrospectively pay him from 1957, when he applied for the job. Green took to the skies for Continental in 1965, going on to become captain just a year later. In 2010, the company dedicated a new Boeing 737 to Green and the CEO Jeff Smisek proclaimed, “He sued us. We fought him. We fought him for six years…and on behalf of my 41,000 co-workers, I’m so glad that he won.”

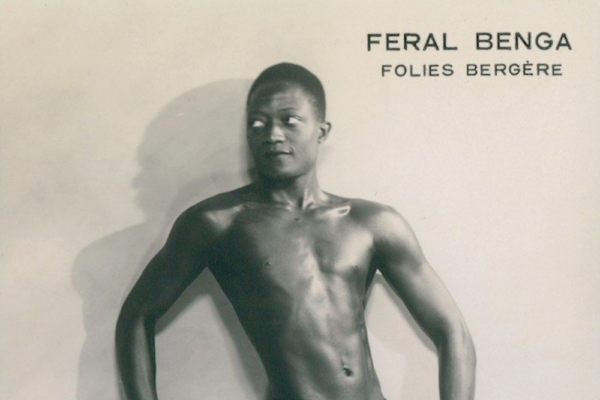

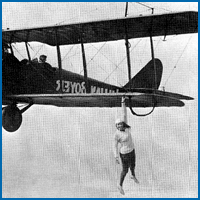

As you might well imagine, if being a Black male pilot for a commercial airline wasn’t hard enough, having two X chromosomes made life that bit harder. For Black female commercial pilots, it would take some pioneering women to be able to break down the cockpit door. Waves had been made as far back as 1910 when French pilot Raymonde de Laroche became the first licensed female pilot. Inspired by this feat and the more liberal attitude to female pilots in France, was Bessie Coleman, who became the first African-American and Native-American pilot.

Now known as Brave Bess or Queen Bess because of her insatiable appetite for daredevil aerial stunts, Bessie was determined to not make race a factor in her career, out right refusing to speak anywhere that upheld segregation or discrimination against African Americans.

In 1920, Bessie set off for France, where she enrolled in the aviation school set up by Gaston and René Caudron. Here she would learn how to loop the loop and perform a number of highly dangerous acrobatic manoeuvres. Less than a year later Bessie earnt her pilot’s license and returned to New York with the right to fly anywhere in the world. Bessie learnt how to please crowds with her endless array of tricks, from wing walking to parachuting out of her plane. Sadly, it was whilst performing in an air show that Bessie was thrown from a plane, where she met her untimely and tragic death at the age of only 34.

For the first Black female pilot to take over the control of a commercial airline, it took over 50 years after Bessie had opened the door for female minorities to get their wings. Jill Elaine Brown was finally granted the right to fly a commercial airliner in 1978. This was in part thanks to her being able to earn enough air miles with a Black-owned airline known as Wheeler Airlines, the first Black-owned airline certificated in the US by the FAA, established by Mr. Warren H. Wheeler after he was turned away from positions in the aviation industry because of his race.

It was through his airline that Wheeler was able to support other African Americans and minority groups get a leg up in the industry, qualifying a large number of Black pilots that were subsequently hired by the nation’s major airlines. One of these people was Jill Elaine Brown who managed to convince Wheeler to employ her as a ticket-counter clerk. From there, Brown earned herself a pilot’s position where she was able to clock up the 1,200 hours, eventually allowing her to get a job for a major airline.

While Wheeler Airlines later filed for bankruptcy and stopped operating in 1986, it paved the way for other Black-owned aviation companies like Blue Crane, Jet It and Bahamas-based Western Air. Operating for two decades, Western Air has a net worth of $90+ million, and flies across the Caribbean. Originally founded by Rex and Shandrice Rolle, their daughter Sherrexcia ‘Rexy’ Rolle now heads up the company. Speaking about the challenges of running a Black-owned airline, the 32-year old Rexy stated in an interview that, “We understand we have to work 10 times harder and we don’t shy away from the challenge.”

There is not enough room in this article to include all those who have fought to make the aviation industry a more diverse place, but what’s clear is that the skies still need to be filled with more people of colour. Sociologists Louwanda Evans and Joe Feagin estimated in 2012 that less than 1% of all commercial pilots in America were Black and fewer than 20 were Black women. In the aftermath of a global pandemic that brought the world of aviation to a halt and prompted us to rethink the way we travel, is this not also an ideal opportunity to rebuild as a more diverse industry? Whilst airline companies pledge to make inclusion a priority in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, the commitments must go beyond tokenism for marketing purposes. As we take the skies once more, let’s hold our airlines to those promises and carry these ideas across the world. It’s time to get on board with the conversation.