For the adventurous of spirit, and those who yearn to pack a bag and disappear to somewhere as remote as possible, arguably nowhere quite captures the imagination as Svalbard. The far flung Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ice lies just six hundred and fifty miles from the North Pole. It may be a place where the polar nights last for four months, closely followed by four months of never-ending sunshine, but Svalbard is home to over two thousand hardy souls, almost as many people, it’s said, as there are polar bears.

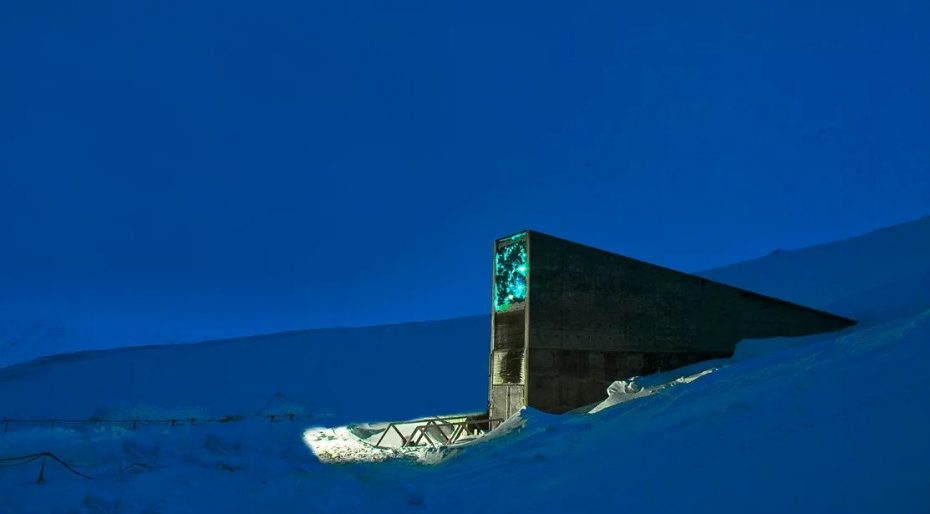

Svalbard is filled with freezing superlatives: it is the northernmost, year-round settlement on Earth, where you’ll find the world’s northernmost church, kindergarten, weekly newspaper, (the Svalbardposten published every Friday), and even a pub. Covered mostly in glaciers, the islands of Svalbard are largely uninhabited, with most people living in the town of Longyearbyen. But dotted around the frozen earth are peculiar glimpses of civilisation: the mysterious looking Global Seed Vault lies half buried in the snow like a fallen alien obelisk; deserted Soviet coal mining towns lie abandoned, preserved in the permafrost as Communist time capsules; and even further north, are the desolate polar research institutes of Ny-Ålesund.

But what draws people to this frozen Arctic wilderness with months of perpetual night? We caught up with one such intrepid adventurer, Cecilia Blomdahl from Sweden, who gave up the creature comforts of Gothenburg to go and live in a simple cabin in one of the remotest places on Earth, the last stop on the way to the North Pole.

“I am originally from Sweden and moved to Svalbard five years ago,” explains Blomdahl. “I was working in the hospitality industry in Gothenburg when I heard about Svalbard for the first time. My boyfriend at the time had some friends that had gone to Svalbard to work for a few months and they got him a job. I thought it sounded super interesting, so I followed along and got myself a job there too. I was only supposed to stay for a few months, but I fell in love with the lifestyle here.”

Part of the appeal of Svalbard is that it is entirely visa-free; although a sovereign part of Norway, a treaty signed soon after World War I means you can simply move there, provided you can find work or support yourself. Regular flights from Norway mean you can have breakfast in Oslo, and be secluded in the Arctic Circle just after lunch. Wander around Longyearbyen, by far the largest settlement in Svalbard, and you’ll come across nomads from as far away as Brazil and Tunisia, who’ve made a home in the freezing cold landscape.

“Living on Svalbard doesn’t have many of the daily stresses of the mainland,” says Blomdahl. “We have no car queues, no commuting time, and things like that. Life is easy, even though we don’t have running water at home in our cabin, life is just simple and beautiful.” Or as one Svalbard explorer put it a century before: “we are seized by an uncontrollable longing for remote places. We want to go further and further into the Arctic lands, the islands in the ice, the frozen earth, which is still lying there as on the day that God created it.”

Longyearbyen maybe one of the remotest outposts above the Arctic Circle, but Cecilia Blomdahl lives even further away; in a simple, cosy cabin ten minutes outside of town, with a Finnish lapphund called Grim for company, and a view out of her window of seven glaciers. “My boyfriend and I were living in a friend’s apartment in Longyearbyen when the cabin came up for sale,” she explains. “Only a few cabins are sold each year, and this one looked really nice so we went and saw it. We fell in love with it immediately and put in an offer. Luckily we won the bidding and had our first real home.”

The landscape may be harsh: Svalbard is made up of sixty percent glaciers, and the rest is barren rock with precious little vegetation. Remarkably, the ground is so hardened from the cold, that there are no burials of the dead permitted here, as bodies simply don’t decompose. But for Blomdahl, Svalbard remains an enchanting adopted home, what she calls a “magical little village in the Arctic.”

For centuries, the only visitors to Svalbard were grizzled hunters, tracking polar bears and Arctic fox furs. The discovery of rich coal seams paved the way for a lucrative mining industry in the twentieth century, but today Svalbard’s main economy is centred around tourism. But a trip to Svalbard is like no other; for one thing, it offers the opportunity to stay in quite possibly the world’s strangest hotel.

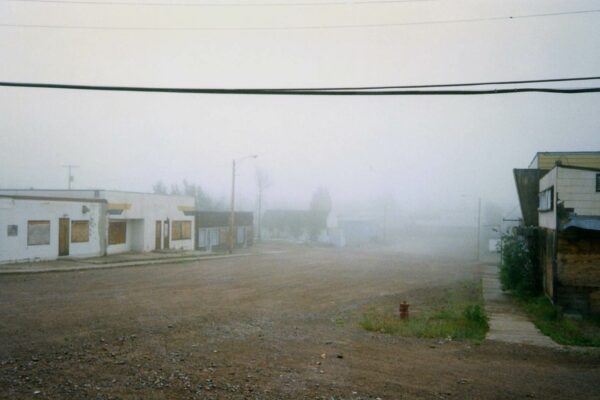

Thirty miles north of Longyearbyen lies a Russian ghost town. Pyramiden was once the jewel of the Soviet coal mining industry in Svalbard, a thriving town of a thousand inhabitants, drawn mostly from Siberia and Eastern Ukraine, working in the rarefied air you find at 79° latitude.

There were other Soviet mining communities in the Arctic archipelago: Barentsburg, located to the west of Longyearbyen, is still a working mine, and home to around four hundred people. Gumant mine closed in 1962, and Pyramiden followed suit in the 1990s, leaving behind a perfectly preserved ghost town, frozen in time in the Arctic.

Due to the cold weather, buildings in Svalbard have a tendency not to decay, leaving Pyramiden looking much as it did during the Communist era. Colourful Soviet propaganda murals decorate the remote outpost, whilst a surviving statue of Lenin looks out over the beautiful Nordenkiöld glacier. The schools, gyms, apartments and shops remain as they were left behind, with pictures on the wall, food on the shelves, and withered potted plants decorating hallways. One Russian reporter from the Barents Observer discovered bottles of the cheap domestic Priviet vodka lying around, and a copy of the transcripts from the 27th Congress of the Communist Party left lying on a desk in the Palace of Culture. He even thought he could still smell traces of papirosa cigarettes lingering in the Arctic air. The only thing missing is the people.

But incredibly, interest in the ghost town has seen a hotel open in recent years. A seasonal staff of eight operate the Hotel Pyramiden, where you can stay in the lap of full Soviet luxury, sip vodka in the hotel bar, and send a postcard from quite possibly the world’s most far flung hotel.

Like most places in Svalbard, getting to Pyramiden is tricky: just 40 km of roads cover a country roughly the size of Belgium, but in the summer, when the seas aren’t frozen, boats carry adventurous explorers to the old mining town from Longyearbyen. In the winter you can only get there by a snowmobile trek lasting three and half hours. “It is always super fascinating to visit both Barentsburg and Pyramiden,” explains Cecilia Blomdahl, “and it is something that we do a few times each year. It really is like visiting a different world, and it is so different from Longyearbyen. Pyramiden is a ghost town, fully abandoned except for the Hotel taking visitors. Barentsburg is still a fully functioning village, with coal mining as their main occupation, but it is worlds apart from Longyearbyen.”

Life in Svalbard, as you’d expect in the Arctic Circle, is dominated by the weather. “We have very specific and distinct seasons here on Svalbard,” explains Blomdahl. “From November to January we have our Polar Night with 24/7 darkness. It is actually my favourite time of year. It’s incredibly peaceful and quiet and just a great time to charge up some energy for the fun season ahead.” As the sun sets for the last time, there is a tradition in Longyearbyen, where the whole village climbs to the top of an old hospital staircase, and the children sing for the sun to return four months later.

“This time of year is also winter, but not our real winter” says Blomdahl. “It might be snowing and cold, or it could be mild with around 0C. The light starts returning in February which is called our blue month. We have hours of blue light and it is just magical. We then have Sunny winter from March to May and temperatures in March often go below-20.”

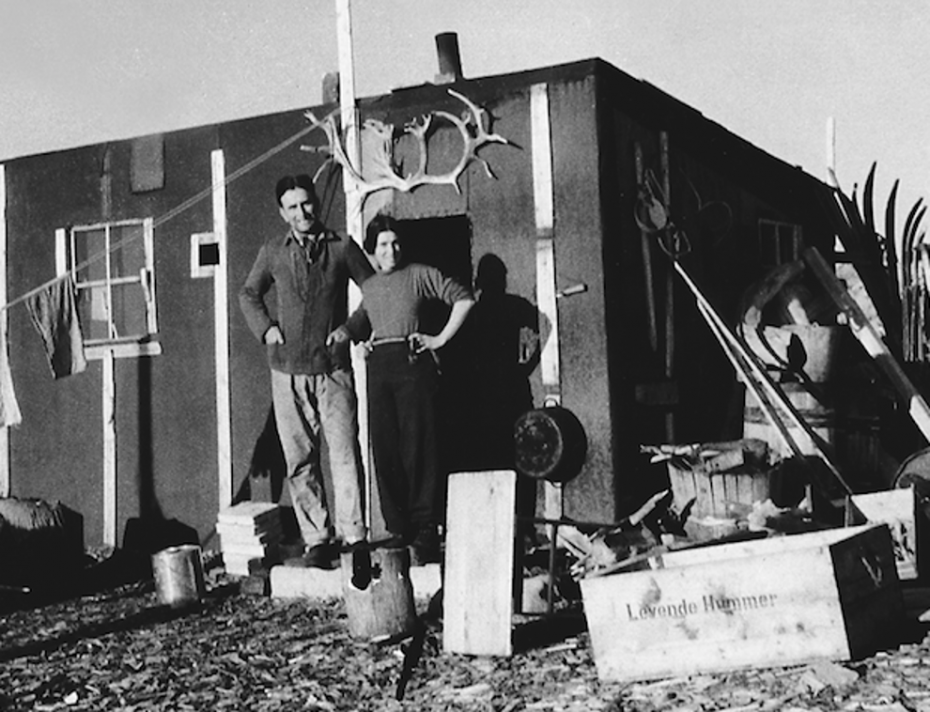

For first time visitors to Svalbard, the polar night can be at first unbearable. Nearly a century before Cecilia Blomdahl decided to move to the Arctic, a young Austrian woman left the comforts of civilised society in Vienna, to spend a year in a remote cabin on the northern coast of the largest island, Spitsbergen. If modern amenities are hard to come by in Svalbard today, they were even more distant in 1933. With no electricity, or way of communicating with Europe, save a mail boat once a year, Christiane Ritter was at first distraught with her decision. “The scene is comfortless,” she wrote in one of the great little known travel writing books, A Woman in the Polar Night. “Far and wide, not a tree or shrub. An arid picture of death and decay.” Incredibly you can take a virtual tour of her cabin here.

But before too long, Ritter would become enthralled with a place where ‘there are no days because there are no nights’, falling under the spell of what Norwegians call ‘Fortryllelse,’ the bewitchments and enchantments of the polar night. In the only book she ever wrote, the pioneering female polar explorer recorded how, “The frozen world lies in untouched beauty; in holy quiet…it is a beautiful, still, and holy night, earth and sky shadowed in a tender cobalt blue. The frozen slopes of the mountains and the coast have no reality; they are a dream lit up by the soft and hazy yellow light of the sun’s reflection as it moves around the northern horizon. And over everything the calm that elsewhere inheres only in the world beyond our own.”

The same beauty led Cecilia Blomdahl to turn her short stay in Svalbard into a new home. “During our sunny winter, February to May, we spend all free time out in the incredible nature, driving our snowmobiles to see glaciers, mountains, maybe even getting to see a polar bear, and we also go stay in small little remote cabins for whole weekends. Our life up here is more focused on nature and adventure.”

Today around fifty different nationalities make up the population of Svalbard, each braving the Arctic temperatures to live in simple dwellings, where the trappings of the modern world pale to the simple pleasures of a pot of coffee bubbling on a cast iron stove. As Christiane Ritter put it nearly a century ago, “We live on a little island as in fairyland, luxuriously and free from care. The stillness of the night, which remains magically bright….Is like a fragment of the mysterious Ice Age. Europe, and everything that binds us to Europe, is forgotten.”

You can follow Cecilia’s adventures in the Arctic on Instagram, Youtube, and Tiktok.