Black women have been at the forefront of many cultural trends throughout the centuries, from hoop earrings worn by ancient Nubian civilisations and 80s disco divas alike, to streetwear trends pioneered by R&B and Hip Hop artists of the 90s. There is one unsung fashion subculture however, which never quite took off with mainstream consumers but for a small group of young Black women on the internet, it became a lifestyle. Let’s take a look at the fashion non-phenomenon known as: Udoli.

In the mid-00s there was a sudden boom of Western intrigue in Eastern culture, particularly Japanese and Korean culture thanks to the rise of social media sites like Myspace, Facebook, and Twitter, which encouraged a wider exposure to trends like anime, K-pop and J-pop. Some of the most popular fashion trends to take off were kawaii fashion subcultures that allow for self-transformation centered around cuteness and doll-like archetypes. Style genres emerged such as “Ulzzang” (ool-jung) a Korean term meaning ‘best face’, “Lolita fashion” highly influenced by Victorian clothing and styles from the Rococo period, and “Gyaru” (the Japanese pronunciation of the word gal), an eclectic Japanese street style with a dizzying array of variations and subcategories.

While these new interests were popular online, they were still largely unknown to mainstream western culture. As a result, westerners with fringe interests turned to the internet to build communities where they could learn more and connect with other teens who shared their tastes in eastern fashion, music, and media. But for darker skinned participants, it turned out to be a different story.

In many Ulzzang groups, it was common practice to hold something known as “best face” contests in which any member of the community could enter and other members could vote or comment on their pictures. But when Black or other darker skinned enthusiasts entered, they were swiftly discouraged. Troubling biases such as the right nose size, bone structure, mouth shape or skin tone came into play and the forums became rife within online bullying. While Asian and white participants were being praised as the most “kawaii” (a Japanese word for cute) or consistently winning the “best face” contests, the message was clear. And when Black and Brown members spoke up about their mistreatment online, they were often dismissed as being overly sensitive.

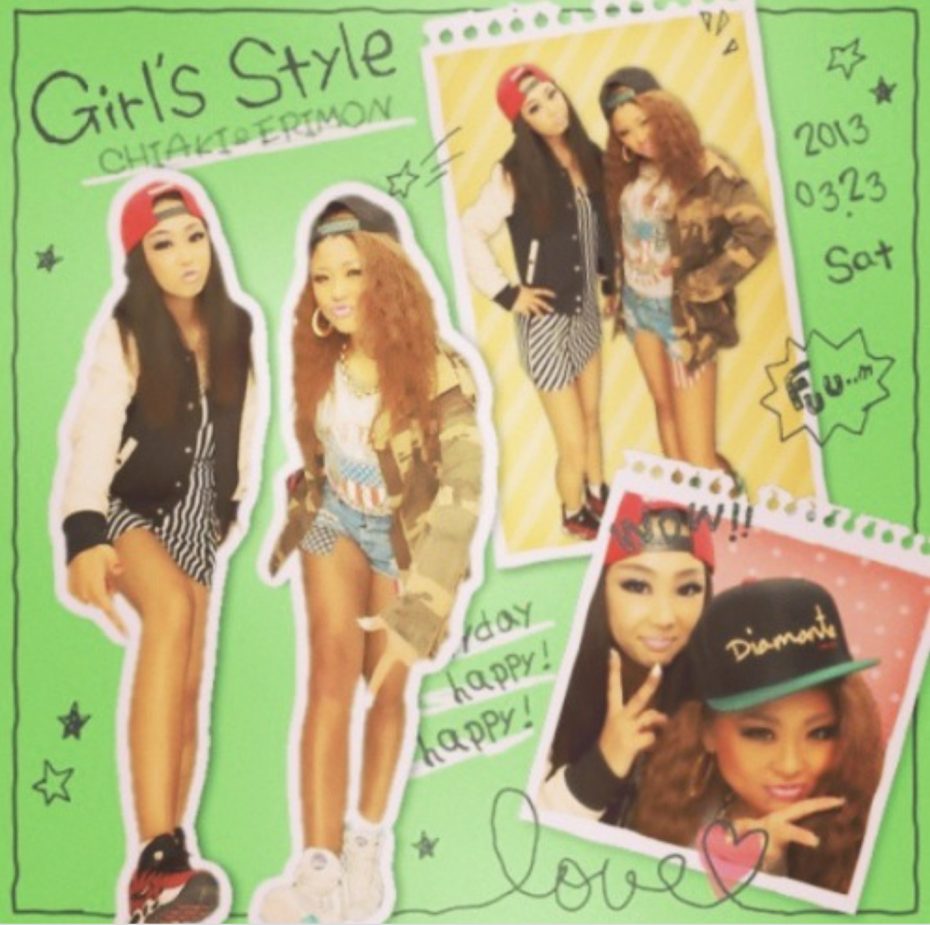

To further complicate matters within the youth subculture, in one niche sub genre of Gyaru called ‘b-Gyaru‘, which draws influence directly from Black American hip-hop culture (yes the ‘B’ does mean what you think it means), Black participants also found themselves excluded and criticised for not being “kawaii” enough.

Despite the fact that many Gyaru girls wore appropriated style such as box braids, acrylic nails, hoop earrings and even darker makeup to achieve a more tanned skin tone, Black girls were even told the make-up didn’t “look right” on them. Black Gyaru members, who were undeniably skilled at recreating the looks and styles of the fashion were often the subject of vitriolic gossip on online hate forums like Gyaru Secrets, a gossip blog for Gyaru girls.

So this brings us to creation of Udoli …

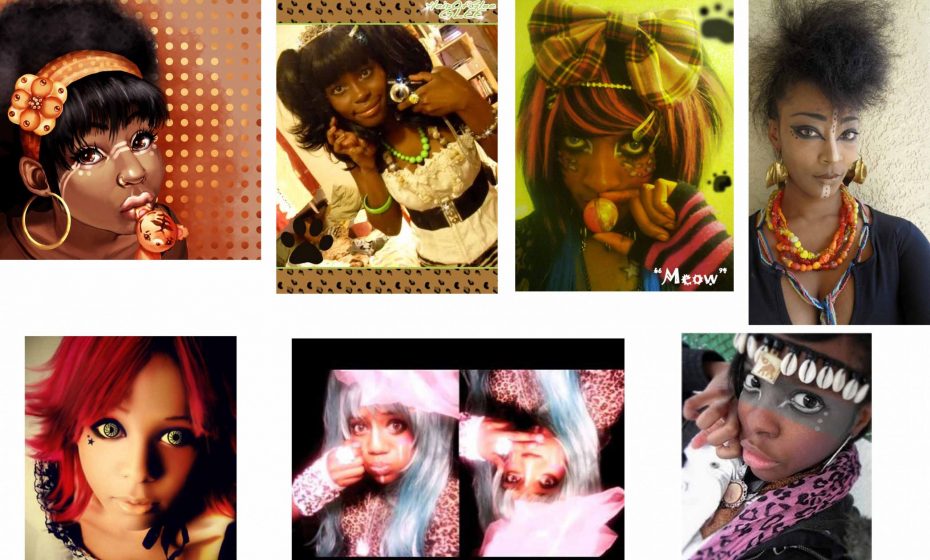

Udoli (the Zulu word meaning Doll) was a subculture of fashion created in 2008 by Ulzzang enthusiast, Vivi Jochan, in response to the discriminatory gatekeeping she had faced from those communities. “A fashion movement that tries to bring out the beauty of different cultures … ANYONE can be udoli,” read the genre’s official byline. The group originally emerged as a safe space for Black and Brown girls who were interested in Gyaru and Ulzzang, a haven for young girls who shared similar interests in music, fashion, anime, and art. Vivi would eventually hand the reins of the burgeoning Udoli movement over to another fashionista by the name, Nuru, who went on to transform Udoli into its own distinct genre of fashion. Nuru envisioned Udoli as a new style altogether, that would centre Black women and provide an alternative to Ulzzang, Gyaru as well as other Asian sub fashions. She, along with a team of other Udoli members, collaborated to conceptualise six different sub categories for Udoli by drawing influence from African, Caribbean, and Native American cultures as well as the already existing Asian styles.

Nuru, was determined to distinguish Udoli as its own style rather than ‘Black ulzzang’ as it had come to be known. This gave all of the members a common goal to work towards and further built up a sense of community. Group members helped to refine the genre by creating their own interpretations of each sub category via YouTube tutorials and lookbooks. The teenage fashionistas created Tumblr blogs, Pinterest boards, Polyvore pages and playlists for inspiration, while other members would use these guidelines to cultivate their own personal Udoli style.

During its most active years, Udoli photoshoots, makeup tutorials and blogs began popping up all over the web as participants endeavoured to spread the word about their subculture. There was even a —now defunct— official Udoli website and contests were held to boost group morale and encourage participation. The community was small, but its participants were genuine in their enthusiasm for the inclusive message and intent of Udoli.

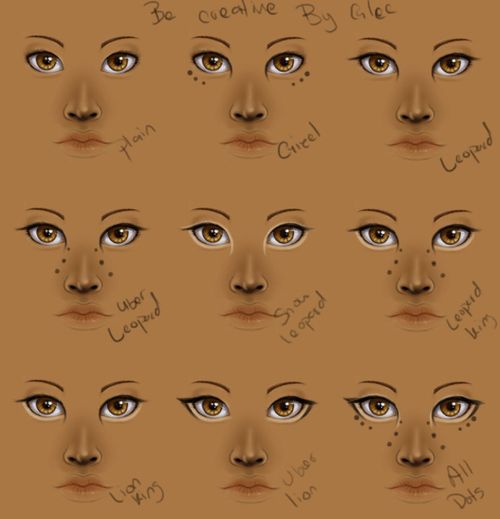

Udoli was not without its detractors, however. Outsiders ridiculed Udoli’s efforts, accusing the genre of “ripping off” Ulzzang and Gyaru. As participation grew, Udoli also faced legitimate criticism regarding cultural appropriation. In a now lost Tumblr post, an African fashion blogger noted that painting cat whiskers and dots on your face was not representative of Africa and that Africa was more than animal prints and face spots. In response to this, an African Udoli member created a visual guide on the significance of dot placements in different African cultures.

Despite these criticisms, the members of Udoli, continued to cultivate and promote the style, but by 2013, Udoli was struggling to retain its veteran members. The founding members who were still around were either more interested in other subcultures, outgrowing alternative fashion, or were experiencing burn outs from trying to mobilize Udoli for so long. A few of the original members who were still around worked hard to revitalise Udoli by creating new contests, Q&A’s, and putting together style guides, but these efforts were in vain more often than not. New girls joining the lifestyle would find moderately inactive groups and eventually, Udoli’s long appointed leader, Nuru, announced her intentions to step away from Udoli, stating that she felt the style had run its course. In 2016, the Udoli Facebook group would cease activity.

Despite its inability to establish itself as a fashion foothold, if nothing else, Udoli highlights Black women’s perseverance and ability to form a sense of community in the face of discrimination. Brief as it was, Udoli is a piece of forgotten Black American fashion history and unquestionably, a product of its time.

As a former Udoli member looking back on myself and these young women, we were simply trying to do what other people are able to do on the internet – just exist and have fun exploring fashion. We might have gone about it the wrong way but we were out there creating a whole new fashion subculture. In a sense, we were ahead of the trends in many ways, because right around that same time, the natural hair movement was taking off as well as the Carefree Black girl movement (arguably pre-Cottagecore). And now we have settled on Black Girl Magic. I will always look back on my time with Udoli with fondness. It will probably never be replicated and should stay exactly where it is, but you had to be there to understand just how special Udoli was.

Written by Shannon Rodgers

Learn more about the Udoli subculture below…