During a visit to The Met in New York, the sight of a full-size Egyptian temple within its walls may no longer faze us amidst the amazing collections that we’re used to seeing in our museums these days. But as you stroll back out into the busy streets, perhaps you might also wonder, hang on a minute – how the heck did the Temple of Dendur end up in Manhattan? And unbeknownst to you, earlier that day three other people may have wondered the same thing in Madrid, Leiden (Netherlands), and Turin (Italy). Each of these cities also has a complete Egyptian temple, given to them by the Egyptian government for each country’s contribution to one of the most ambitious UNESCO projects ever undertaken and the greatest archaeological rescue operation of all time.

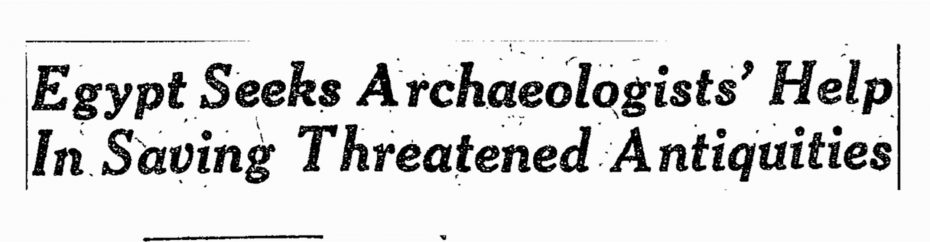

It was during the midst of the the Cold War, that the UN’s Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) managed to coordinate an International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia and complete “40 technical missions by teams from five continents.” The project ran from 1960 to 1980 and saved many temples and other sites from being submerged by the planned but reservoir of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile River near the Egyptian-Sudanese border. The controversial dam, intended to control the annual flooding of the Nile, was announced in 1954 and completed in 1970, with the reservoir reaching capacity in 1976, and the UNESCO program ran from 1960 to 1980.

From the very beginning, the US and the Soviets competed for influence over the project. The dam was ultimately designed by a firm in Moscow. Before construction began, the Suez crisis heightened the bargaining tension between Egypt and the various countries offering to lend money for the project. President Nassar ultimately accepted Soviet funding, and later in 1959 the Egyptian and Sudanese governments asked the UN for assistance in moving the threatened monuments.

Lake Nassar, as the reservoir was named, is so large it can be seen from space, and without the coordinated work of the UN campaign, it would have submerged 22 major monuments and architectural complexes up to 50 meters under water. The international teams also accomplished a remarkable amount of “excavation and recording of hundreds of sites and the recovery of thousands of objects.”

The US, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands received the temples in the 1970s. Spain was the only government to place their temple (The temple of Debod) in an outdoor setting, and discussions about protecting it from the elements are under review after a scathing visit from an Egyptologist in early 2020.

The Italian government granted the Temple of Ellesyia to the Museo Egizio in Turin, the second largest collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts outside of the Egypt, which has been a center for the study of ancient Egypt since the early 19th century. The Netherlands granted the Temple of Taffa to the National Museum of Antiquities where it was reconstructed so the public could view the remarkable building before having to pay admission.

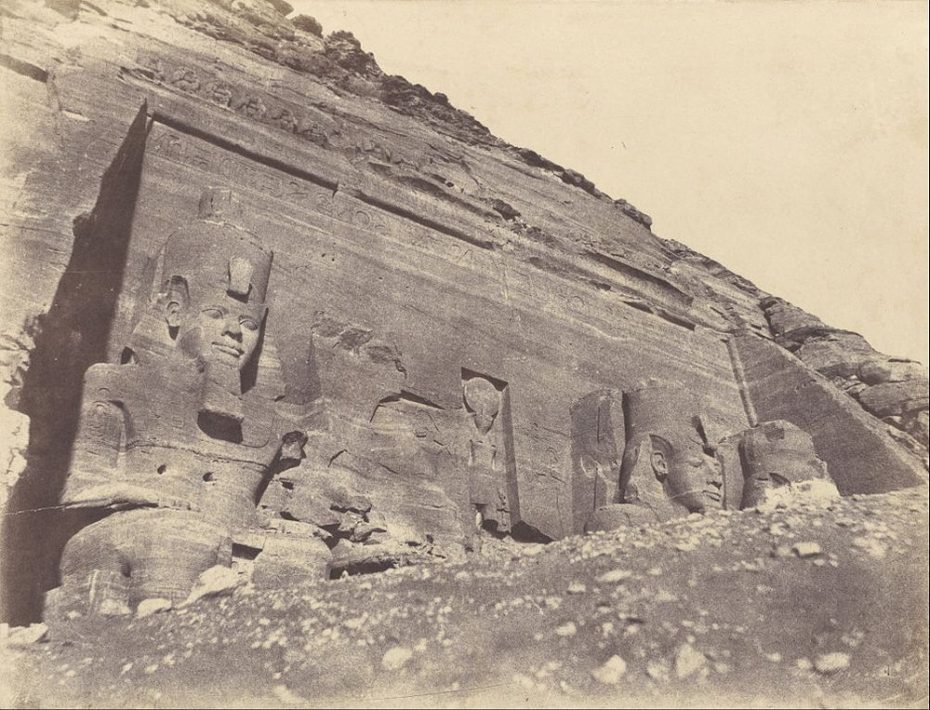

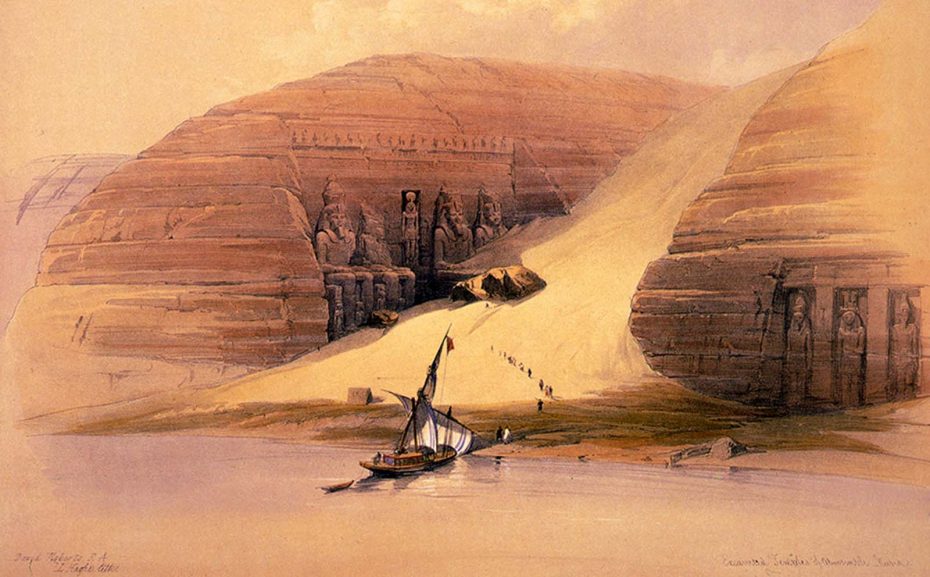

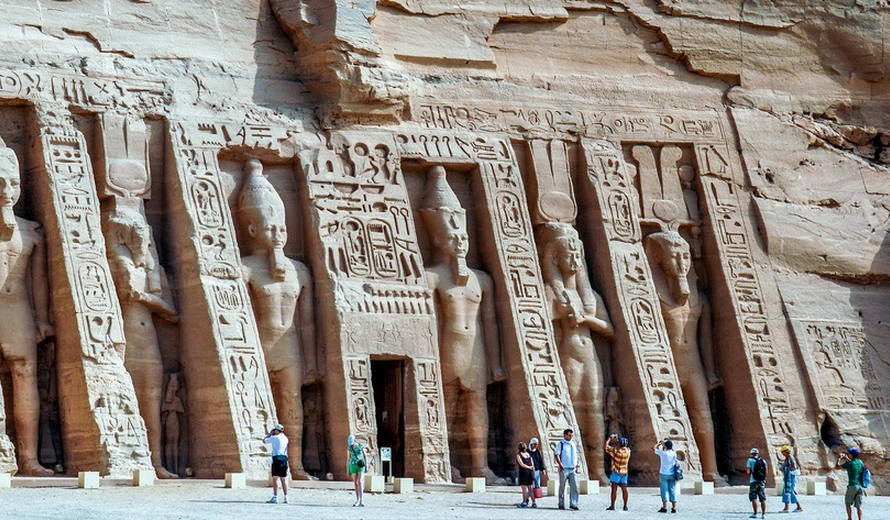

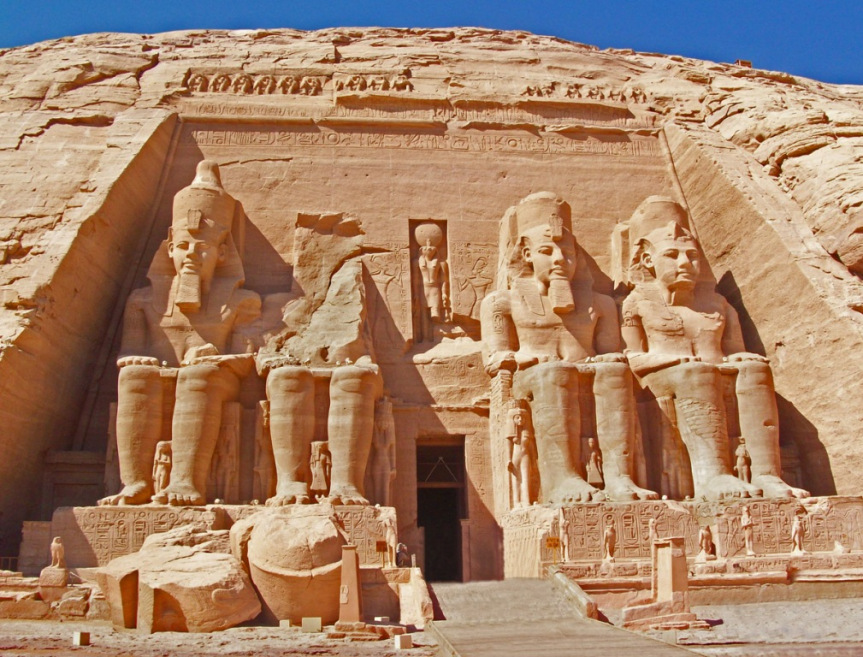

These four temples are only a tiny sample of the heritage saved by the Nubian Salvage Campaign. The most impressive project by the campaign was without doubt the relocation of Abu Simbel, a pair of three thousand year old rock-cut temples down river from Philae…

The region of Nubia was important to the Egyptians as a source of gold and other goods. The temples were part of a decades long building spree by Ramesses II, who wished to demonstrate the might of his dynasty and spread Egyptian culture to the area we know as Sudan. They were constructed over twenty years and dedicated to Ramesses II and his wife, Nefertari. As the temples fell into disuse over a few hundred years, the desert covered the site, and the temples were lost.

During the Napoleonic wars, an unusual Swiss scholar, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt was hired as an explorer by the African Association, which promoted exploration and understanding of the African continent and eventually the abolition of the slave trade. He learned the Arabic language and regional customs by traveling throughout the Middle East disguised as a poor man, and while in Egypt in his last years of training, he uncovered the top of frieze one temple and thankfully shared his discovery with a fellow explorer before dying tragically young only a few years later. He is most famous for being the first modern European to visit Petra, the capital of the great Nabatean empire, the year before he uncovered the temples at Abu Simbel.

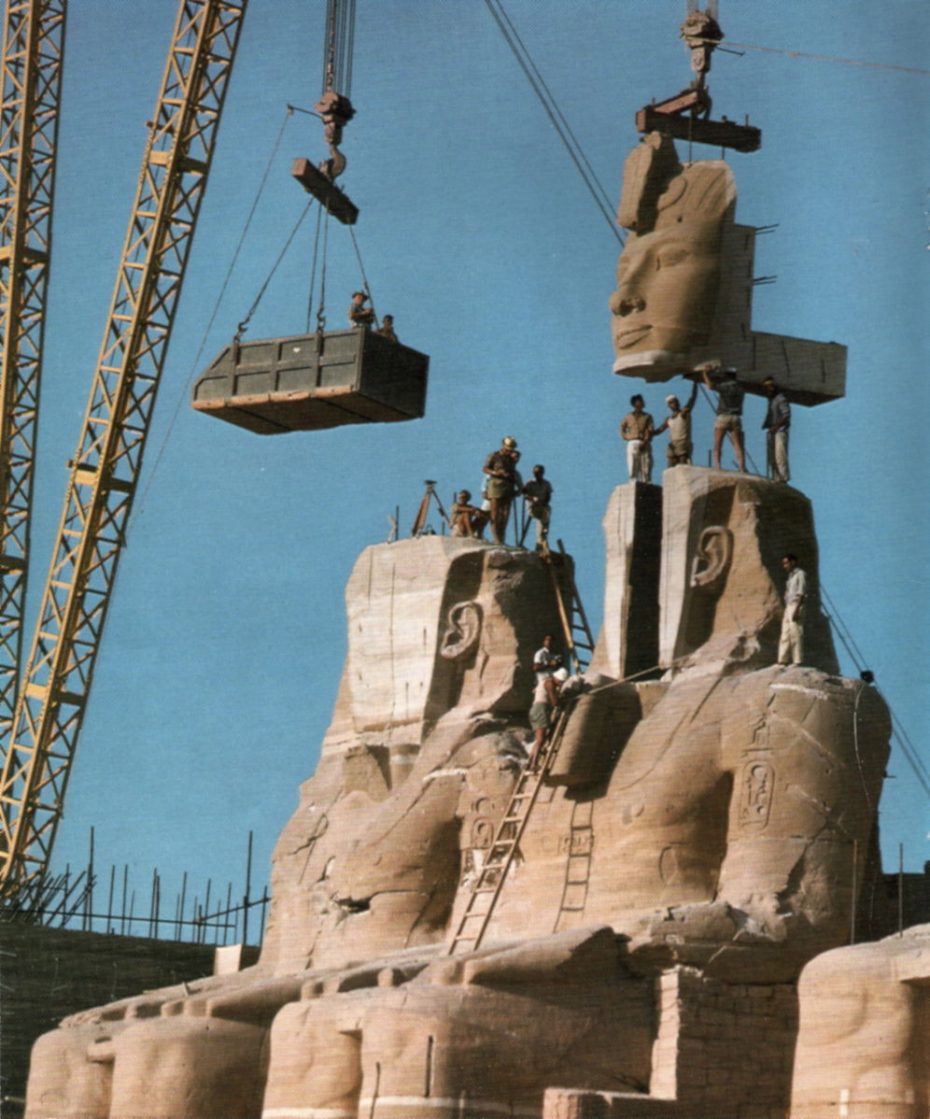

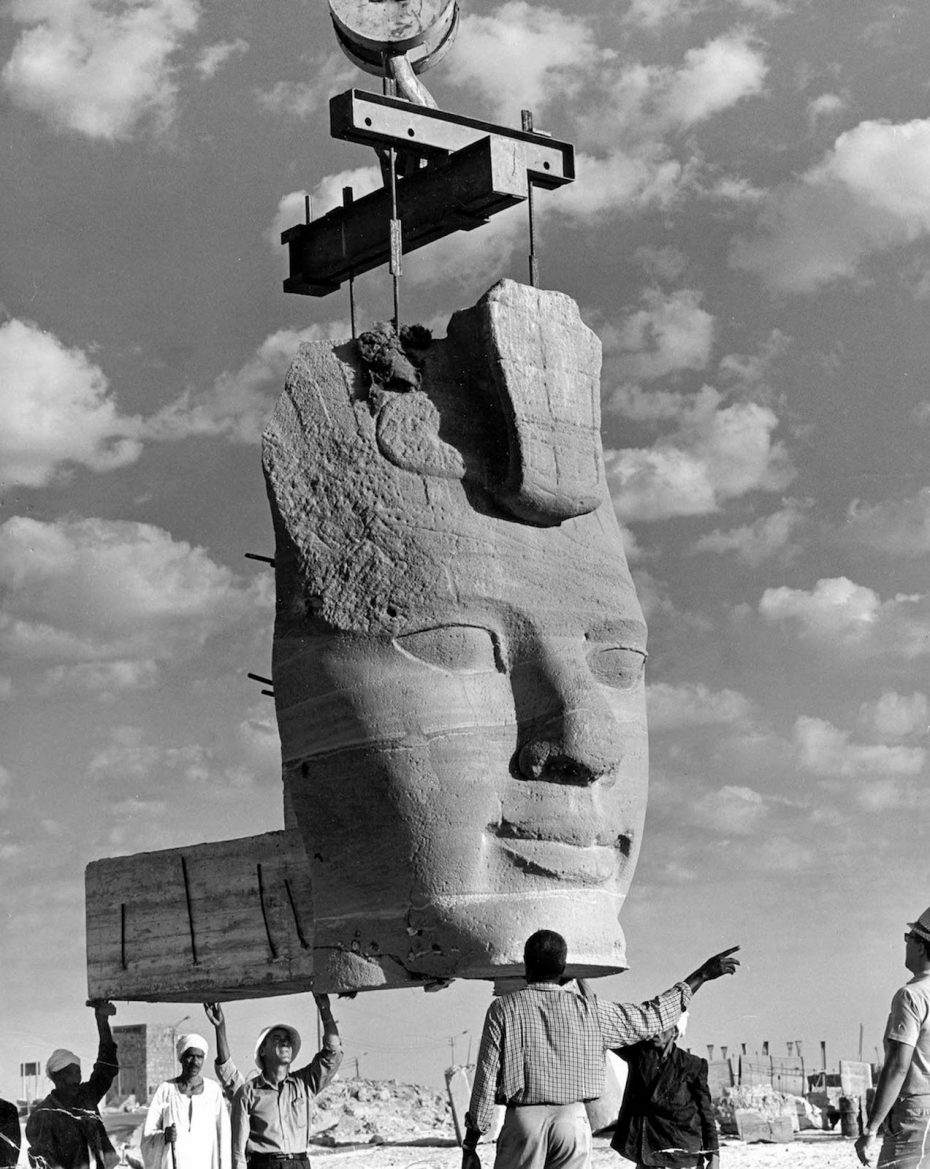

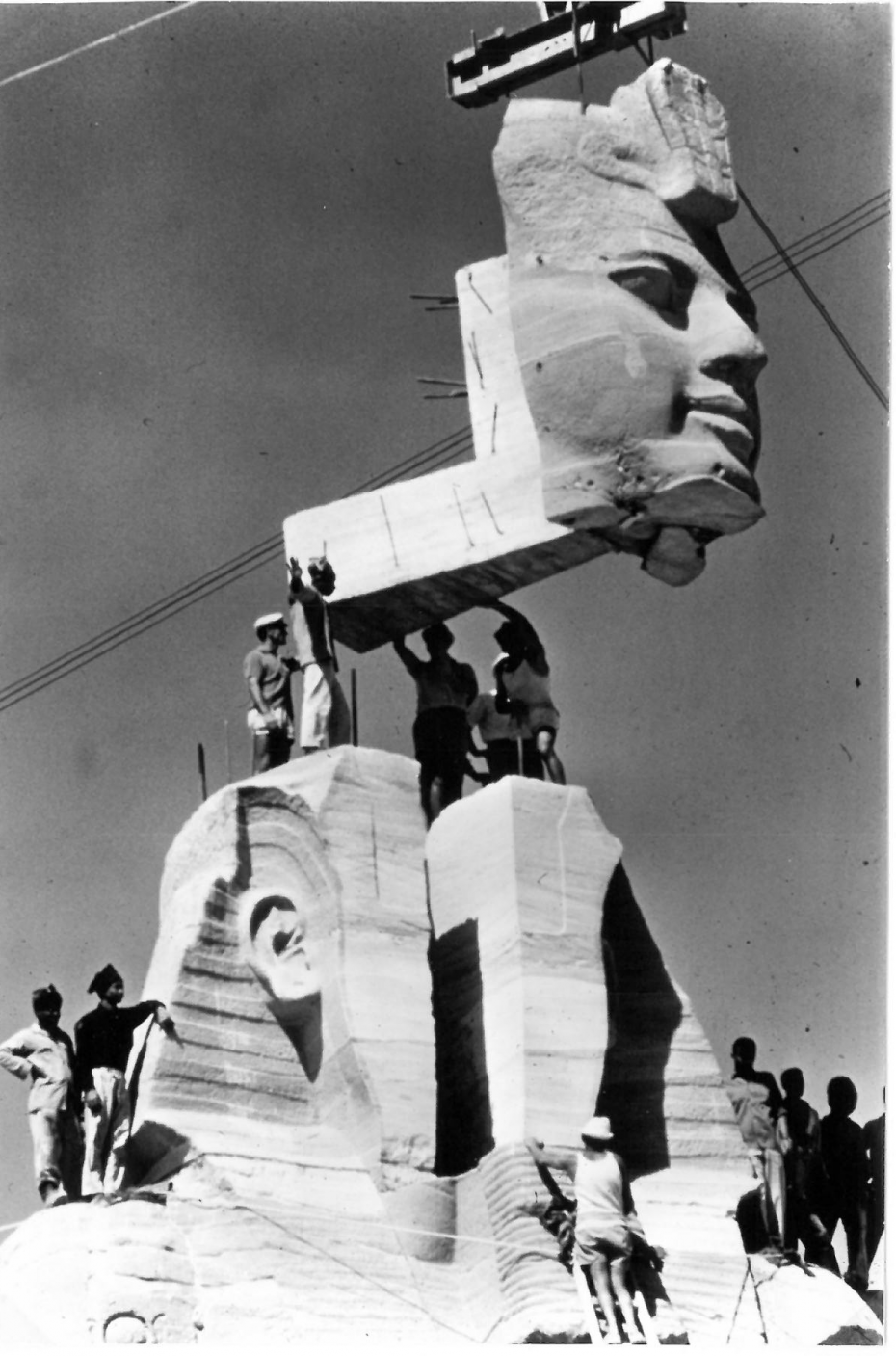

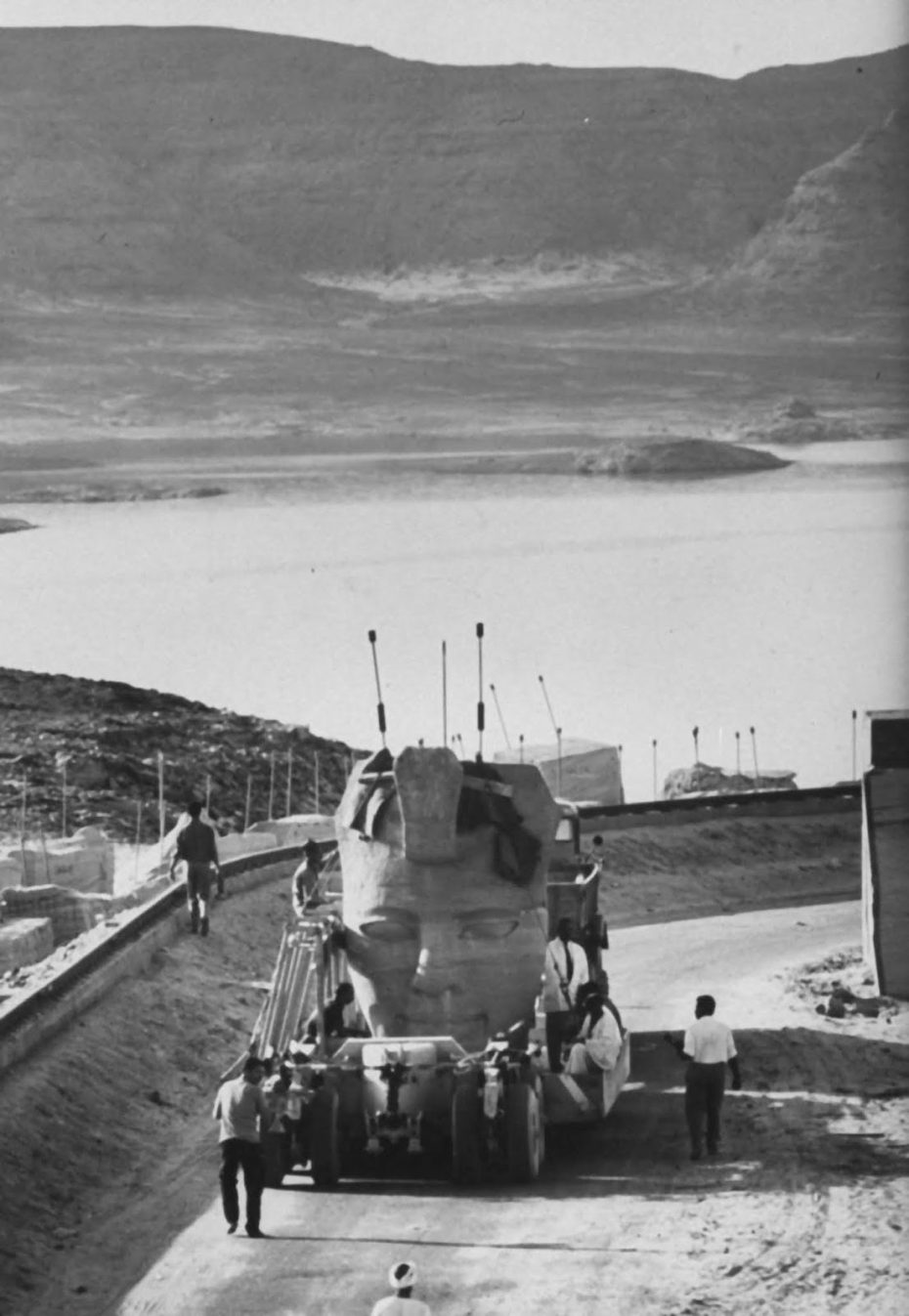

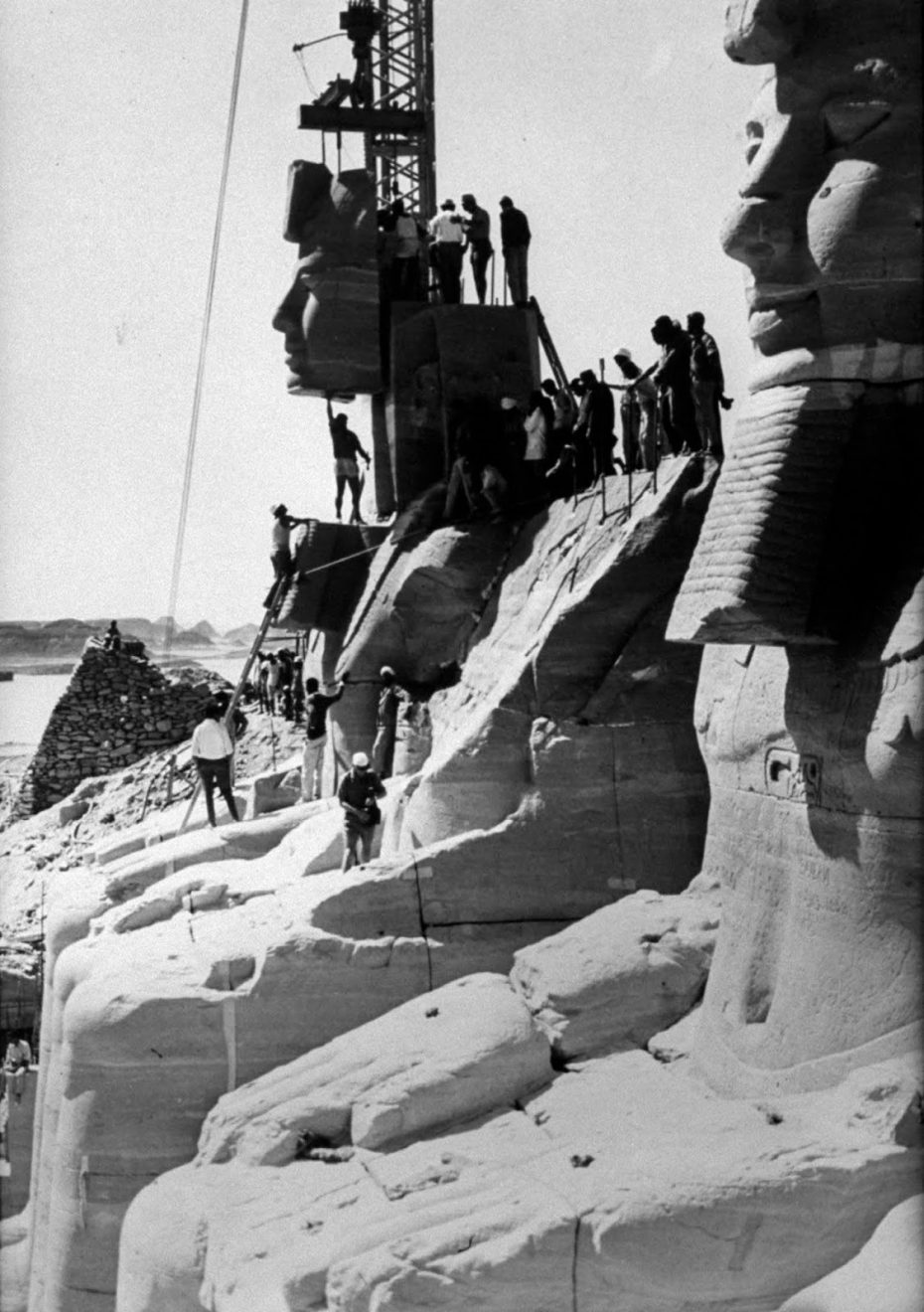

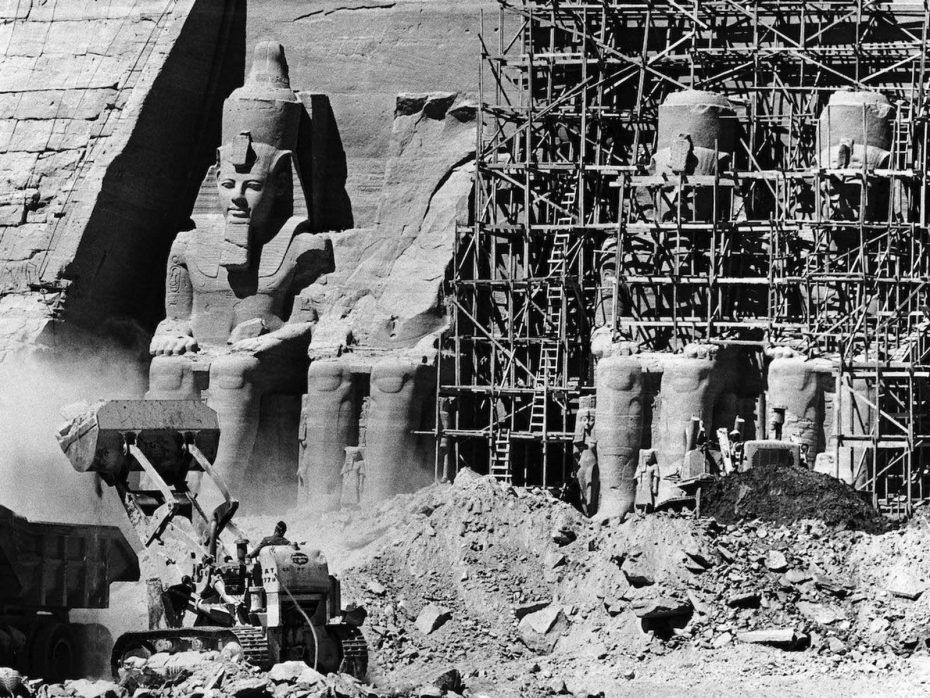

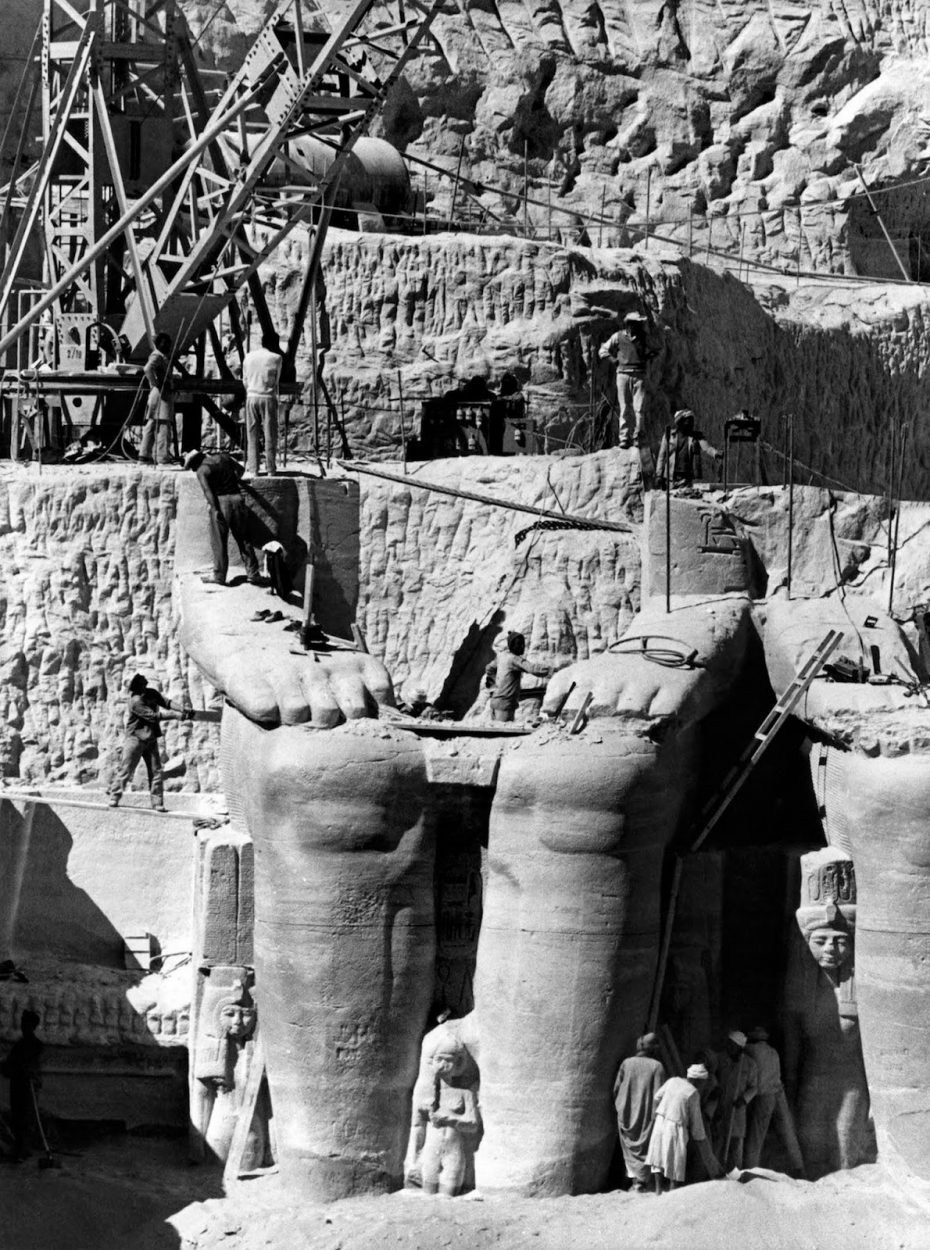

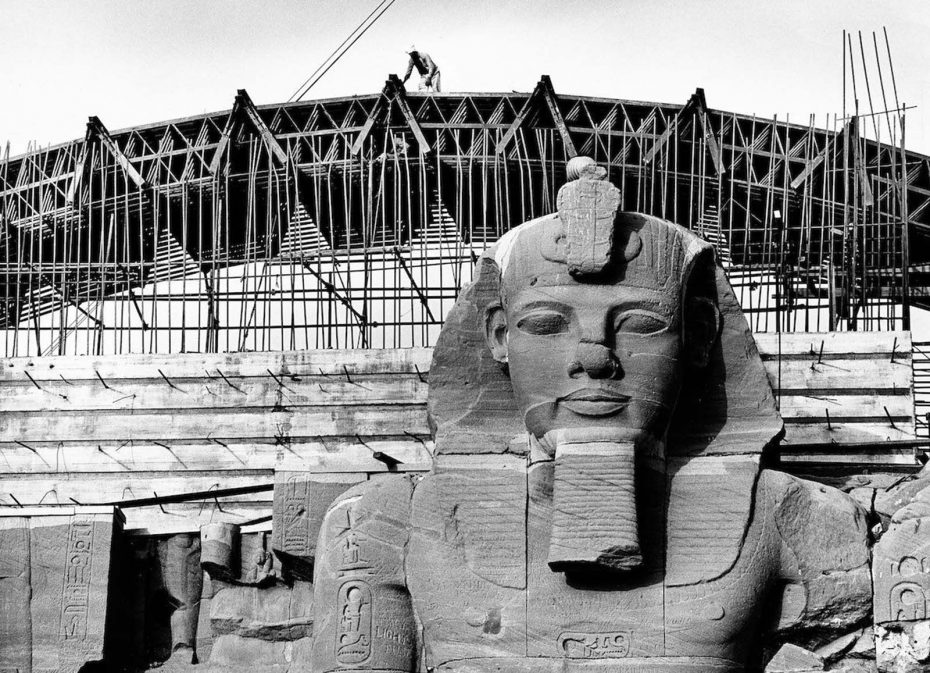

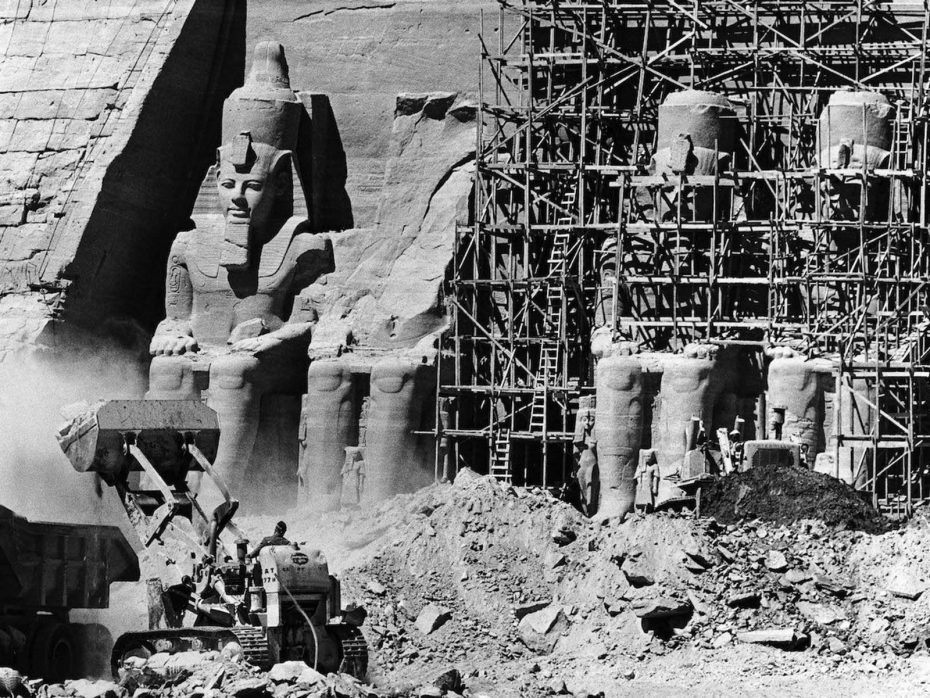

Even after the new dam was complete and Lake Nassar had begun to fill, no plan had been accepted for relocating Abu Simbel. Understandably, suggestions such as enclosing the temples in glass as a submarine tourist destination or cutting the temples loose and floating them to higher ground were rejected. By the time the decision had been made to cut the statues and temples into manageable blocks averaging 20 tons each, a coffer dam had to be built to hold back water from the area.

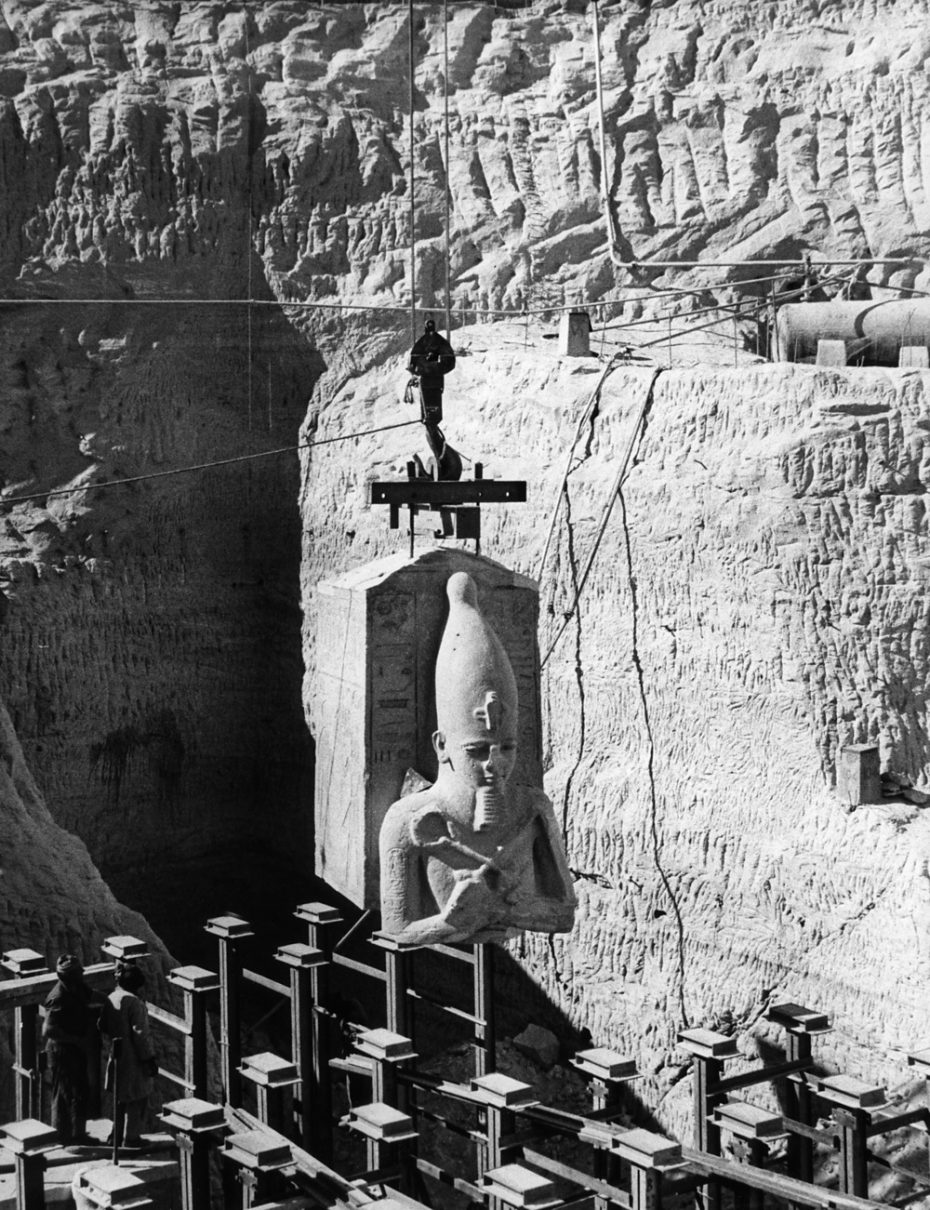

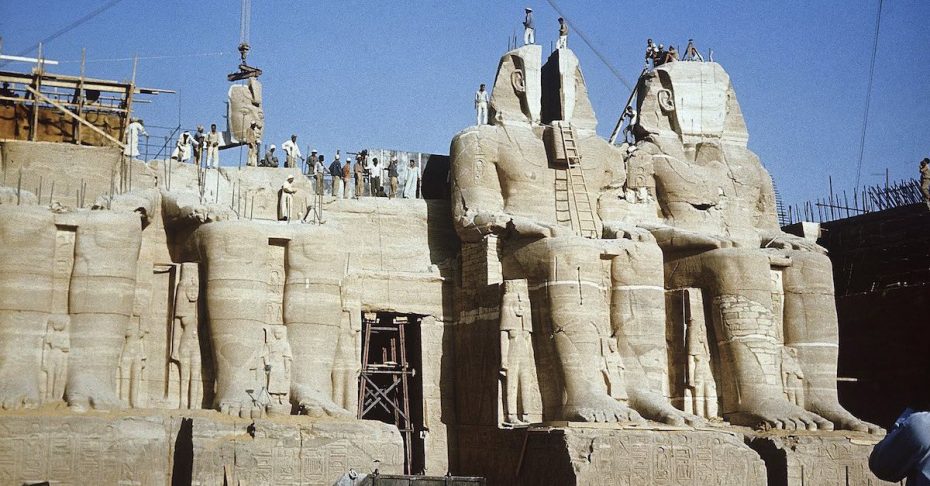

“Beginning in November 1963, a group of hydrologists, engineers, archaeologists and other professionals set out on Unesco’s multi-year plan to break down both temples, cutting them into precise blocks (807 for the Great Temple, 235 for the smaller one) that were then numbered, carefully moved and restored to their original grandeur within a specially created mountain facade.

Workers even recalculated the exact measurements needed to recreate the same solar alignment, assuring that twice a year, on about 22 February (the date of Ramses II’s ascension to the throne) and 22 October (his birthday), the rising sun would continue to shine through a narrow opening to illuminate the sculpted face of King Ramses II and those of two other statues deep inside the Great Temple’s interior. Finally, in September 1968, a colourful ceremony marked the project’s completion.”

This silent movie shows some of the challenges the team of experts had to deal with.

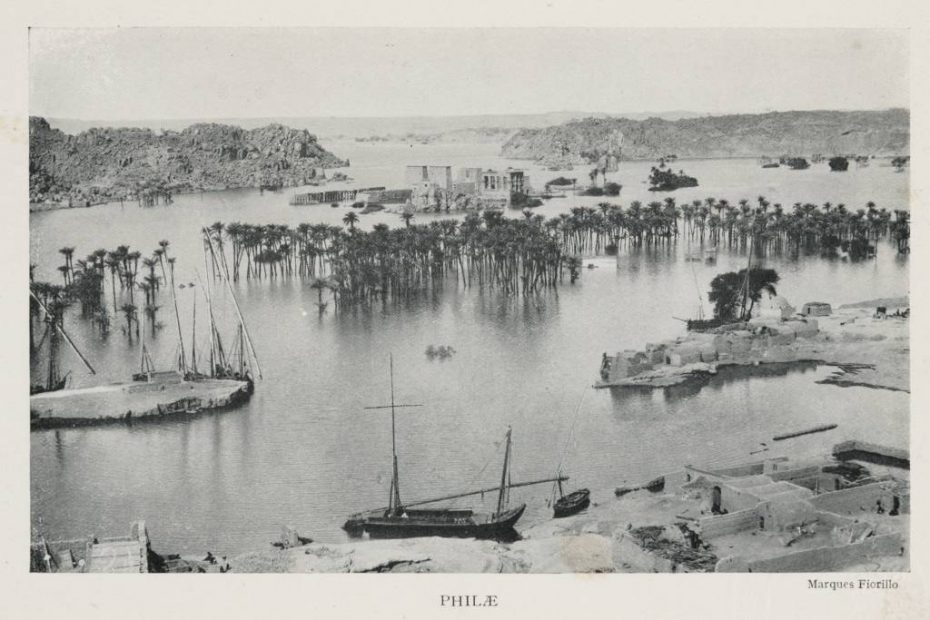

Another famous set of buildings was a temple complex on the island of Philae dedicated to the goddess Isis and later converted to a church in the 6th century. As an example of the scale of work accomplished by the incredible international teams, it took three years to move the temple at Philae 500 meters away to higher ground. The sacred buildings had stood in the Nubian valley region for thousands of years surrounded by lush island plants and visited by priests. Legend said neither birds flew over it nor fish approached its shores.

By the 1950s however, the temple at Philae had spent nearly 50 years flooded by the Nile after the construction of the Aswan Low Dam in the 1902. The beautiful complex had silted up and the colors of the reliefs had been washed away.

To access the site, a large dam had to be built specifically for the work, and then the buildings were dismantled into about 40,000 units ranging in size from 2 to 25 tons. The reconstructed buildings were moved to safe ground on another nearby island.

These sites have become popular tourist destinations despite their distance from any major city. “International expertise and funds [that] were mobilized to dismantle and reassemble six groups of monuments in new locations [and the] scale of the 20-year project and the immense technological challenge it generated were unprecedented in UNESCO’s history…” and the success of the campaign inspired the creation of “UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention and the inscription of sites on UNESCO’s World Heritage List,” which have come to include places like Venice’s lagoon, Vienna’s Historic Centre, Cambodia’s Angkor Wat.

As a grand gesture of thanks, Egypt gifted four complete temples to the largest donor countries so that unassuming visitors to places like the Met can experience a small taste of the 3000 years of Nubian history their country helped to save. Here’s a snap of one of those ancient gifts traveling down 5th Avenue towards the Met.

Today, the Temple of Dendur, which was awarded to The Met by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967 after Egypt gifted it to the United States, is one of the most familiar works of art at The Met. And while most visitors will leave without understanding just how the hell it got here, you’ll know the full story behind the great rescue of Egypt’s drowning temples.