When we think of an heiress, we tend to picture an overdressed spendthrift sipping a top shelf cocktail from an expensive crystal glass; her eyes mischievously peering over the rim telling stories of glamour, sex and scandal. Heir to the Cunard shipping dynasty, Nancy Cunard was known for all of that too; her paramours included Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Langston Hughes and Man Ray to name a few. And Nancy’s unconventional and eccentric style regularly drew great interest from the fashion world, as was generally the case with any “It-girl” worth her salt. Unlike so many others in her circle however, this heiress also dedicated her life to fighting racism, fascism and challenging the colonial attitudes of her British upper class background long before the rest of the world caught on. She was a poet, a publisher and muse to many writers and artists of the 1920’s to 1930’s, but Cunard was also the poster girl for how to use your privilege for good.

Cunard was born to a wealthy family in the late 19th century Britain; her father, a new-moneyed baron who bought his nobility through his economic success, her mother, the “perfect” society hostess. Nancy’s relationship with her parents was strained to say the least, in fact, according to a New York Times article, she “grew up to despise everything her parents and their class represented.” As a young girl, she was shipped off to several boarding schools through France and Germany, one of which was run by British poet Virginia Woolf, but her intellectual mentor would turn out to be her own mother’s secret lover, novelist George Moore, who would inspire her own writing career. She impulsively married a professional cricket player at the age of 20, followed by a divorce two years later, and then … well, then the affairs get more interesting.

She “played tennis” regularly with Ernest Hemingway, got very cozy with James Joyce and became a muse to Constantin Brancusi. According to documents from the British intelligence agency MI5, Cunard also had a secret affair with Indian socialist leader V.K. Krishna Menon. Langston Hughes said Nancy Cunard was “one of my favorite folks in the world.” The American poet William Carlos Williams, who kept a picture of her in his study, deemed her “one of the major phenomena of history.” Not everyone had kind things to say about her though, and one of her lovers wrote that he thought she derived “personal satisfaction” from hearing that a lovelorn man might kill himself over her.

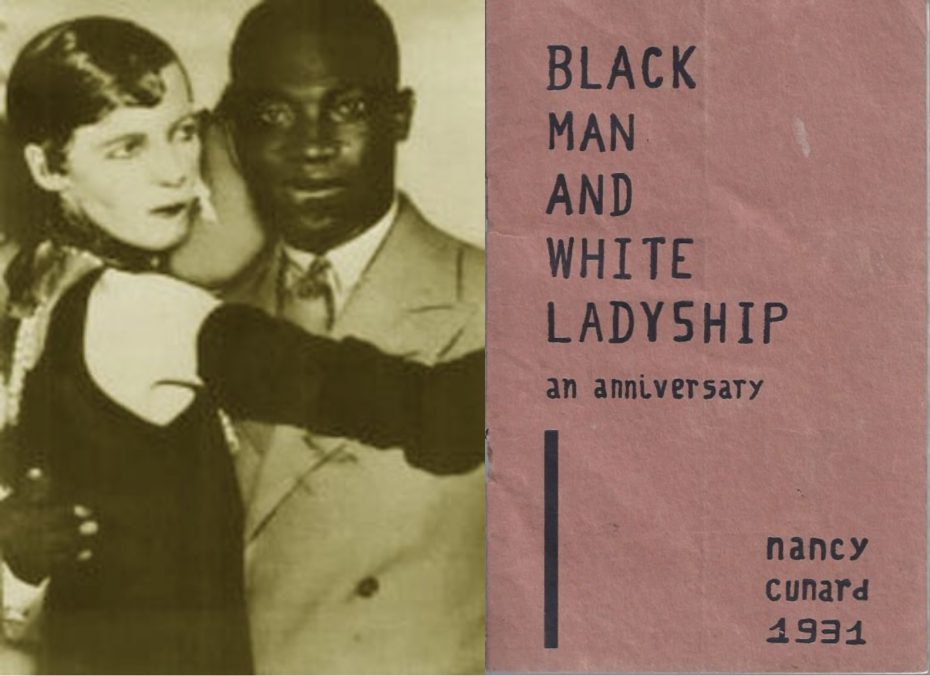

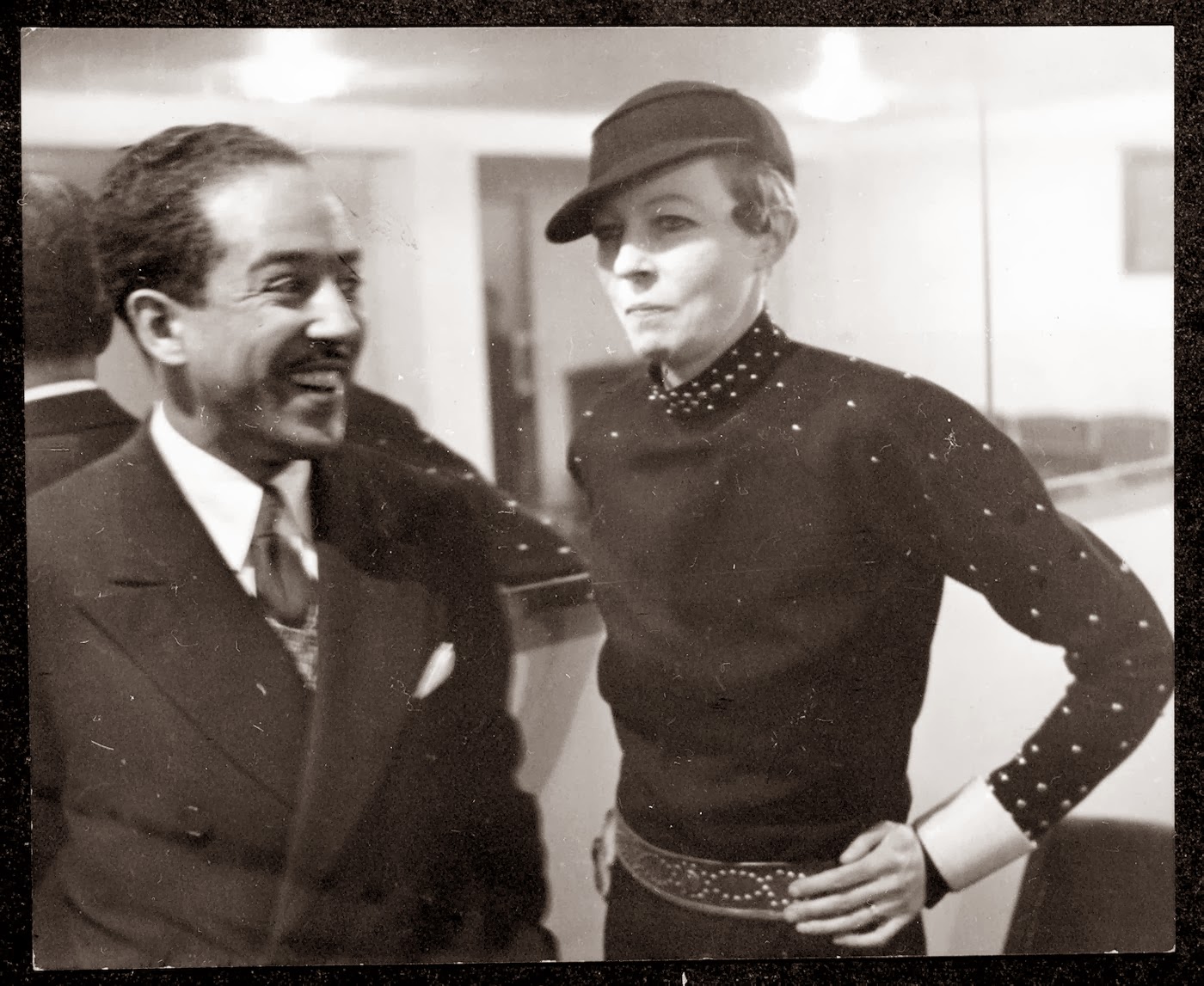

However, Cunard’s most notable or “news-worthy” love affair at the time, was with an African American jazz pianist Henry Crowder, a relationship that revealed the racist attitudes held by many of her society friends and family. As one British tabloid newspaper put it when they featured the heiress on their front page, “Miss Cunard’s association with colored friends has been a bombshell to titled London”.

When her mother heard of the relationship, she asked, “Is it true that my daughter knows a Negro?” and went on a rampage to tear them apart. In 1931, Nancy published a pamphlet that defended interracial relationships, entitled Black Man and White Ladyship, attacking racist attitudes as exemplified by her mother.

Cunard and Crowder eventually went their separate ways and the jazz musician later published a book detailing their relationship in which he exposed her infidelity as well as her alcoholism, but Cunard often said that her relationship with Crowder “made” her, and changed her life’s direction toward righting injustices against people of colour, particularly Black people in North America and Europe.

They had met in 1920s Paris, where Nancy had been living with the novelist Michael Arlen and fallen in love with the Dada and Modernist movements. During her relationship with Crowder, her personal style blossomed into something quite extraordinary…

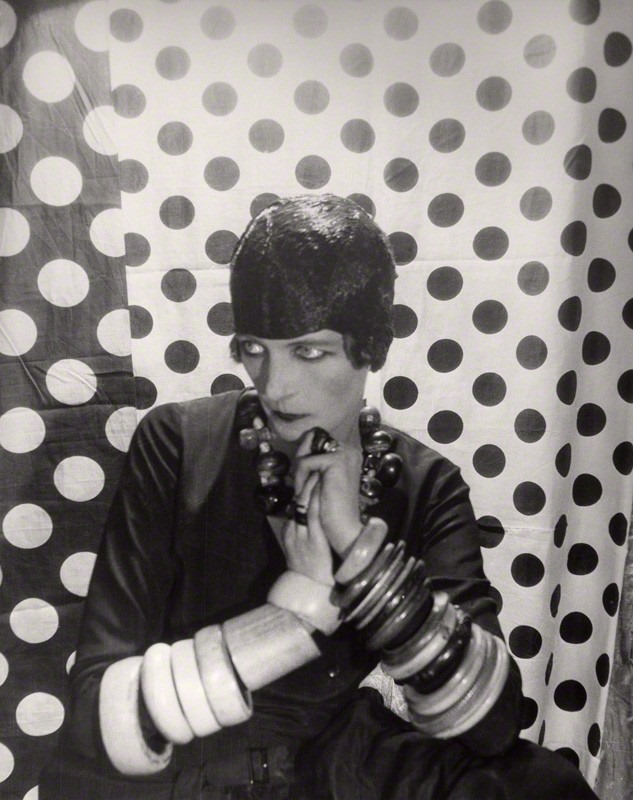

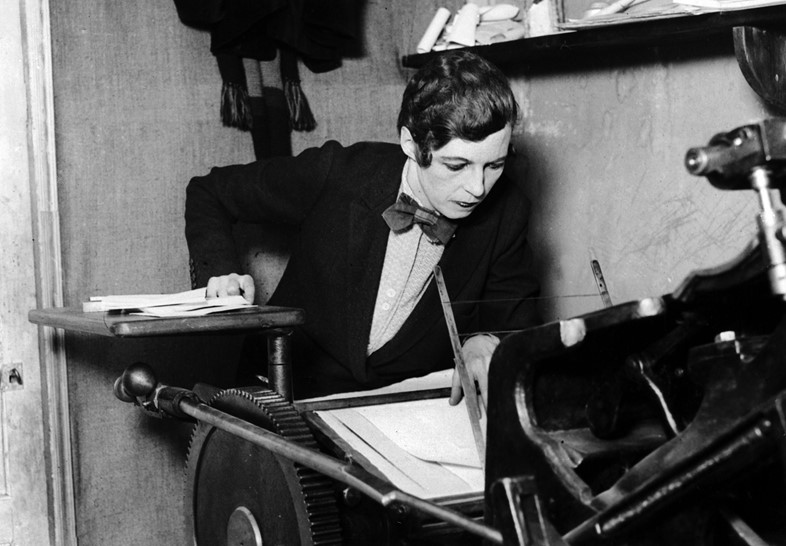

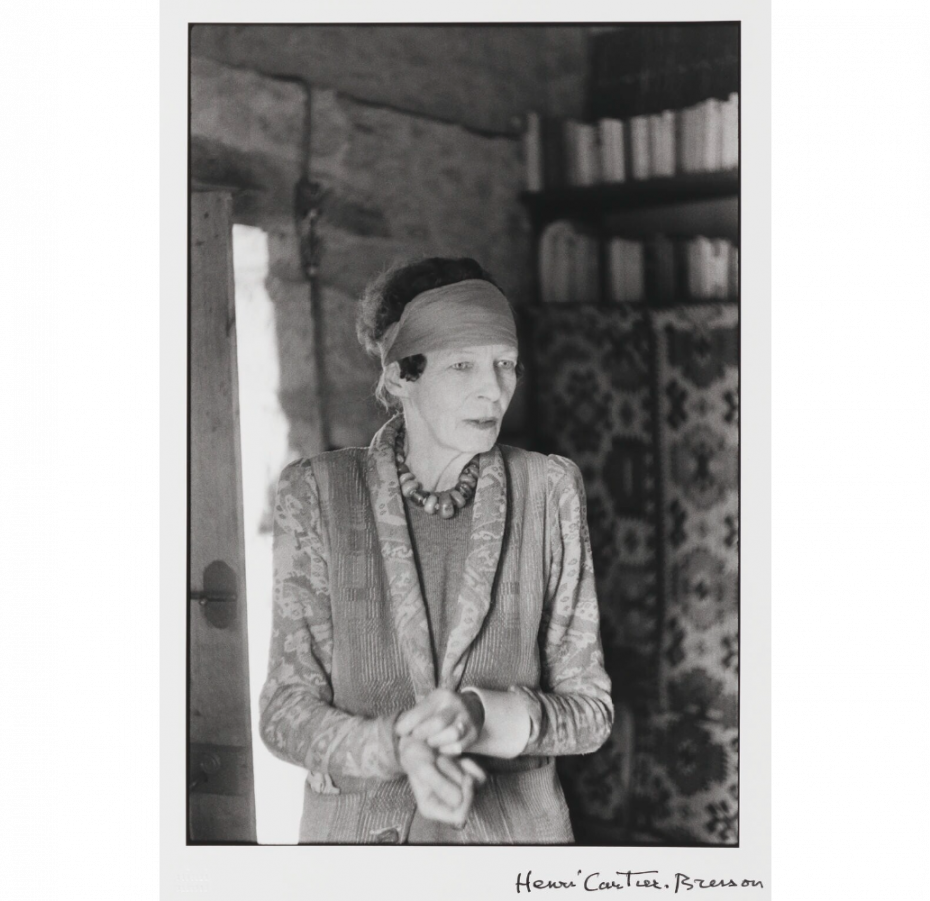

She cropped her hair short in the Garçonne style of the Jazz Age, wore androgynous clothing and kept her eyes heavily lined with black kohl. Among her most notable accoutrements were the dozens of ivory, gold, and wooden bracelets she wore all the way up to her elbows. Fashion brands including Gucci and Erdem have since created collections inspired by Cunard’s style.

Her striking image was captured by experimental artists and photographers of the early 20th century including Man Ray. She embraced African jewellery, a style never seen before on white women, while fashion critics brazenly called Cunard’s style “the barbaric look”.

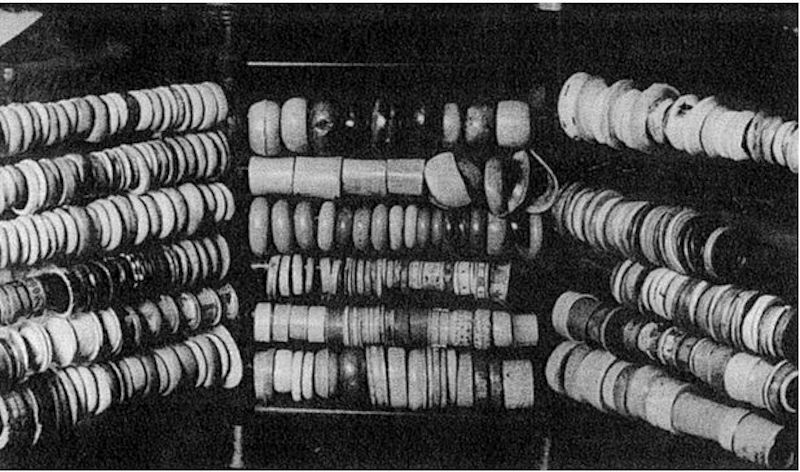

During the Jazz Age, she wrote three books of poetry in the 1920s and took over The Hours Press and began to explore and promote Black literature. Under her guidance, it became the publishing house for the most daring writers of the Jazz Age. Nancy joined in the growing surge of the Civil Rights Movement, advocating for the release of the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers who had been falsely accused of assaulting two white women in Alabama. She organized the British Scottsboro Defense Fund, a charitable organization which demonstrated and raised money for the defense. Fellow writers Rebecca West and Virginia Woolf also supported the fund, but despite their best efforts, the Scottsboro Boys were convicted.

Although it would cost her both her family and her fortune, a few years later, Cunard used her personal funds to publish a tome of poems, stories, essays and other ephemera that represented the range of the Black experience, entitled Negro. She called it a “symposium,” but other critics have called it “an avant-garde ethnography.”

The list of 155 contributors is wildly impressive, too. The symposium included contributions by W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes, as well as well-known white writers like Ezra Pound and Samuel Beckett. One contributor, Nnamdi Azikiwe, would even go on to become the first President of Nigeria. Despite its urgent message and extensive scope, the press didn’t give it much attention and it was banned in a number of British colonies, resulting in overall poor sales. An abridged version of the anthology was released in 1970, but original copies of Negro were all but impossible to find until 2018 when the full, unabridged version of Negro was published for the first time since its original publication in the 1930s.

In the mid-1930s, while fighting for equality of race, gender, and class, Cunard also began to advocate for communist causes, though she never formally joined the Communist Party, and was known to have proclaimed herself an Anarchist. While working as a reporter and translator for the French Resistance in World War II, she compiled an anthology of poems celebrating the cause that reportedly earned her a position as one of Adolf Hitler’s personal enemies. Nancy also served as a freelance correspondent in Spain during the Spanish Civil War, denouncing Franco’s brutality. But she didn’t just use her pen – she rolled up her sleeves and established a shelter to feed thousands of his victims; Spaniards who had spent time in concentration camps across the French border. In the post-war years, she traveled to other war-torn nations, especially former British colonies and settled briefly in the Caribbean in an effort to better understand the effects of colonialism. When she returned to England in 1948, it was alongside more than a thousand Jamaican immigrants, the first of a wave of West Indian immigrants to arrive in England following the war. Back in Britain, Nancy worked with Black communities to archive Black history and led a campaign to safeguard the African collections in the Liverpool Museum. It was almost as if nothing could stop her…

Rather tragically, Nancy Cunard’s later years were plagued by mental illness. She leaned heavily on the self-medication of alcohol, losing control of her finances and was eventually committed to a mental hospital after an argument with police turned physical. She died penniless and alone in a hospital in Paris two days after she was found face down on the streets weighing less than sixty pounds (27kg). As Cunard’s biography puts it, “her body had wasted away in a long battle against injustice in the world. Her reward was a life that had become progressively lonelier, and a god-forsaken death.”

It’s a heartbreaking end for our forgotten heiress whose devotion and contributions to the struggle for racial justice could perhaps inspire a few modern-day socialites to use their privilege for less luncheons and more action in a fight for the oppressed. One of Nancy’s lovers, the famous French poet Louis Aragon once said, “It’s impossible to discuss the intellectual history of the early 20th century without discussing Nancy Cunard”. So let’s discuss her. Let’s share her story and put her back in the history books where she belongs.

Further reading: Nancy Cunard: Heiress, Muse, Political Activist by Lois Gordon.