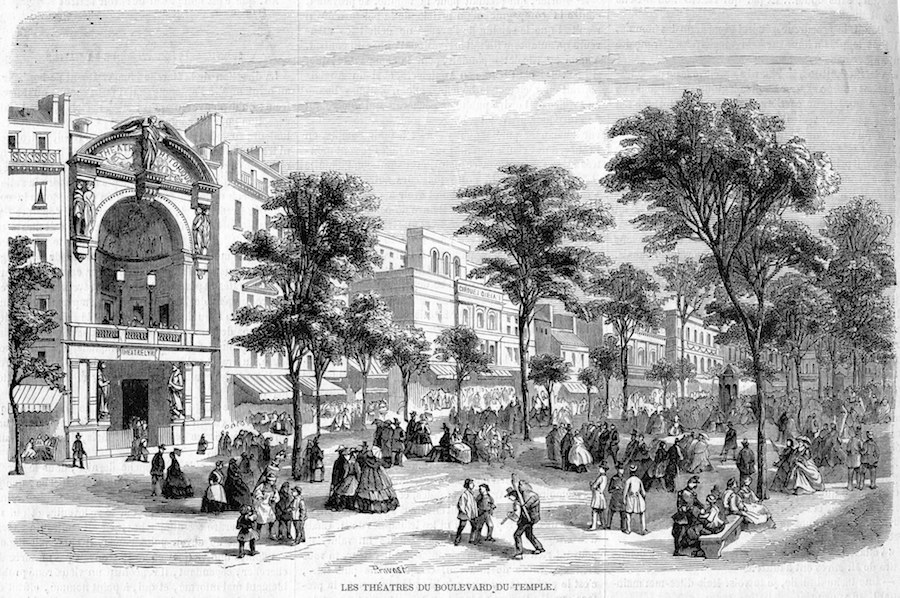

The Boulevard du Crime, a nickname for the Boulevard du Temple in Paris, could not be more of a misnomer. It was never the refuge of thieves or scoundrels but rather in the 19th century, this street was a joyful nocturnal Right Bank hotspot; a 24/7 carnival with a host of cabarets, cafés and most notably theatres specialising in crime melodrama – hence the Boulevard du Crime. While almost all of the theatres were destroyed in 1862 during Baron Haussmann’s great rebuilding of Paris, this street, today a shadow of its former itself, is cemented in the French capital’s artistic legacy.

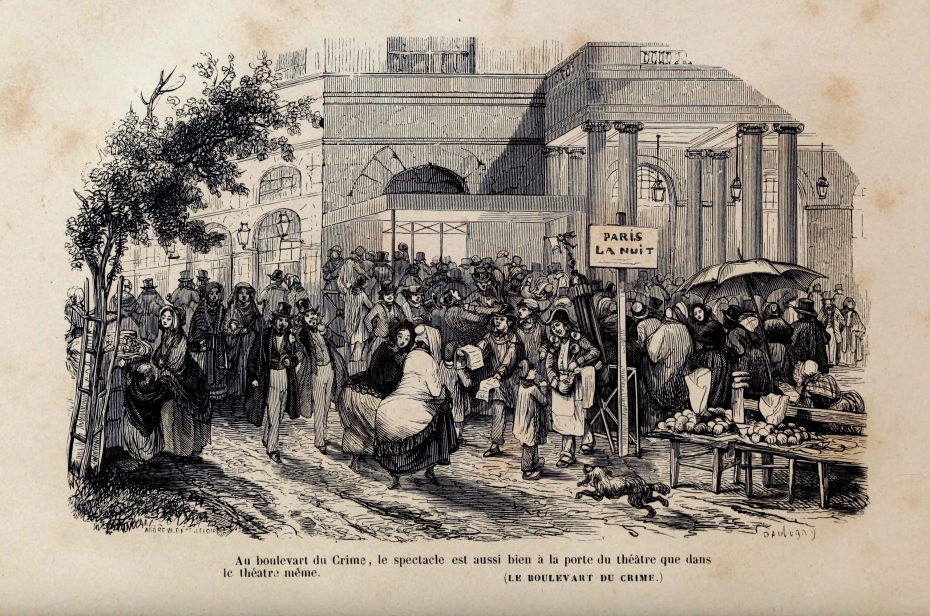

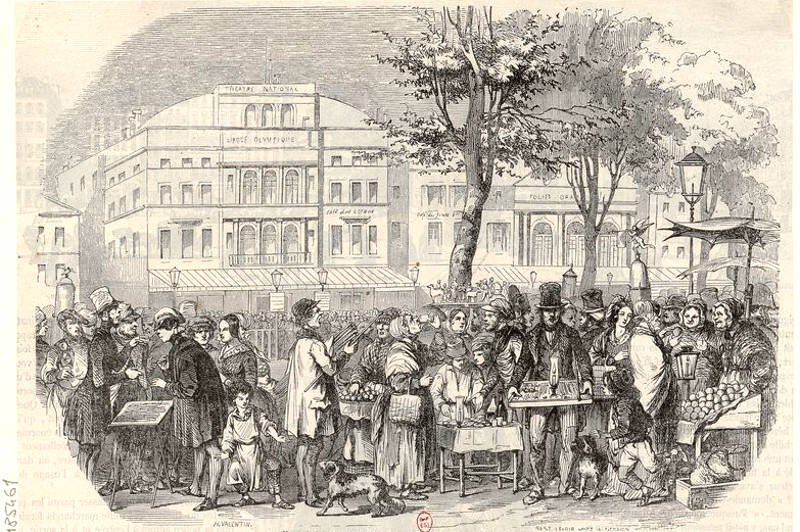

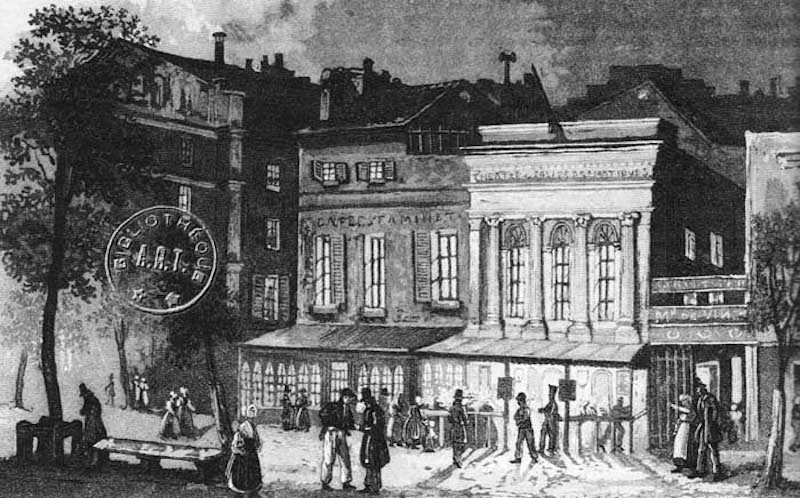

Starting in the 1700s, Boulevard du Crime, which straddled the 3rd and 11th arrondissements, developed its artistic reputation, with many venues attracting a diverse crowd of Parisians looking for escapist entertainment. Even just walking down the street was a form of entertainment, with actors and acrobats performing “extracts” (a sort of theatrical trailer) from the balconies.

Melodramas quickly became the most popular genre amongst Parisian audiences, portraying the struggles towards the end of the Industrial Revolution, always with a dramatic and often immoral flair. The theatres were so successful that during its heyday, the street known as boulevard du Temple was officially renamed the Boulevard du Crime.

A notable departure from high society, melodramas were the people’s drama; thrillers spinning tales of addiction, orphanhood and prostitution. They were popular throughout Europe and around the world, but had a particular cultural relevance in France, influenced by the French Revolution and the decreasing role of elite institutions. Historian, Professor Jim Davis described them as a sort of new morality, “a bible for secular times.” Dramatic scenes were mixed with satire and music to fit the mood of a scene. Mélodrame after all, did first refer to a musical style.

Author Lucian W. Minor also noted that these works solicited violent emotions from their working-class audience who were increasingly moving into the city of Paris to sustain the industrialised economy. Fruit sellers would allegedly line the sidewalks of the boulevard selling rotten fruit for audience members to throw at the stage. Sitting on rather uncomfortable wooden plank seating, “men and women came to sob, smile and cheer at melodramas, crude, in prose, but always ending happily.”

And it truly was a genre for the masses. In a 1905 book about Boulevard du Crime, Henri Beaulieu counted the “crimes” committed on the theatrical street over a 20-year period: “Tautin was trapped 16,302 times, Marty was poisoned 11,000 times with various toxins, Fresnoy was immolated in different ways 27,000 times. Mlle Adèle Dupuis was 75,000 times innocent, seduced, kidnapped or drowned. 6,400 capital charges have tested the virtue of Mlle Levesque, and Mlle Olivier, hardly entered the career, has already drunk 16,000 times from the cup of crime and vengeance; here are, unless I am mistaken, 132,902 crimes to be paralleled between five individuals who, however, enjoy excellent health and general esteem.”

There was however, one infamous real-life crime that took place on the boulevard in July of 1835, when Giuseppe Marco Fieschi led an assassination attempt against King Louis-Philippe. Around 400 projectiles were volleyed at the king, who was accompanied by three of his sons and an entourage of officers. While the king was not gravely injured, 18 people died and Fieschi was tried and executed.

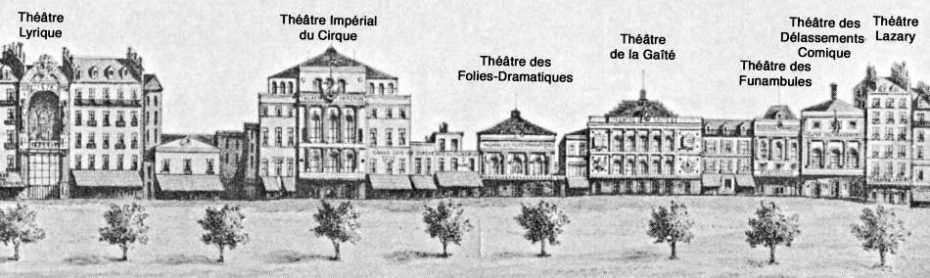

The theatre of Boulevard du Crime either reenacted or invented its theatrics however, whether it was staging the storming of the Bastille at the Théâtre du Cirque or a sensational street battle deploying state of the art pyrotechnics (which caused one building to burn to the ground).

The Théâtre de la Gaîté was one of the most well-known house for melodramas under the helm of René-Charles Guilbert de Pixerécourt, a playwright and theatre director. One of his most notable works is The Dog of Montarges, based on a 14th century legend about the murder of a king’s courtier whose dog was the only witness to the crime and pursued the killer to seek justice. The piece was so popular it was translated and performed in the United States, England and Germany, where famed literary figure Johann Wolfgang von Goethe tried to stop the production, saying he would have nothing to do with a theatre where a dog was allowed to perform.

Melodrama wasn’t the only genre that developed on the Boulevard du Temple. Famed dancer Marguerite Badel (who went by the stage name “Rigolboche”) is credited for popularizing the can-can at the Théâtre des Délassements-Comiques. The Théâtre des Funambules (“The Theatre of the Tightrope-Walkers”) was at first a meeting place for acrobats and later hosted mime performances by Jean-Gaspard Deburau, whose character Pierrot became a model for the pantomime art form. Deburau was portrayed in Marcel Carné’s 1945 film “Les Enfants du Paradis” (“Children of Paradise”), which was filmed during Vichy-occupied France, depicting an escapist vision of Paris and Boulevard du Crime. Marlon Brando once described it to Truman Capote as “maybe the best movie ever made.”

Boulevard du Crime’s heyday ended with Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s upheaval of Paris infrastructure in the name of urban renewal. In 1862, Haussmann decided to enlarge the Place du Château d’Eau to what’s now Place de la République, ordering all theatres to be torn down. The last performances were held on July 15th that summer.

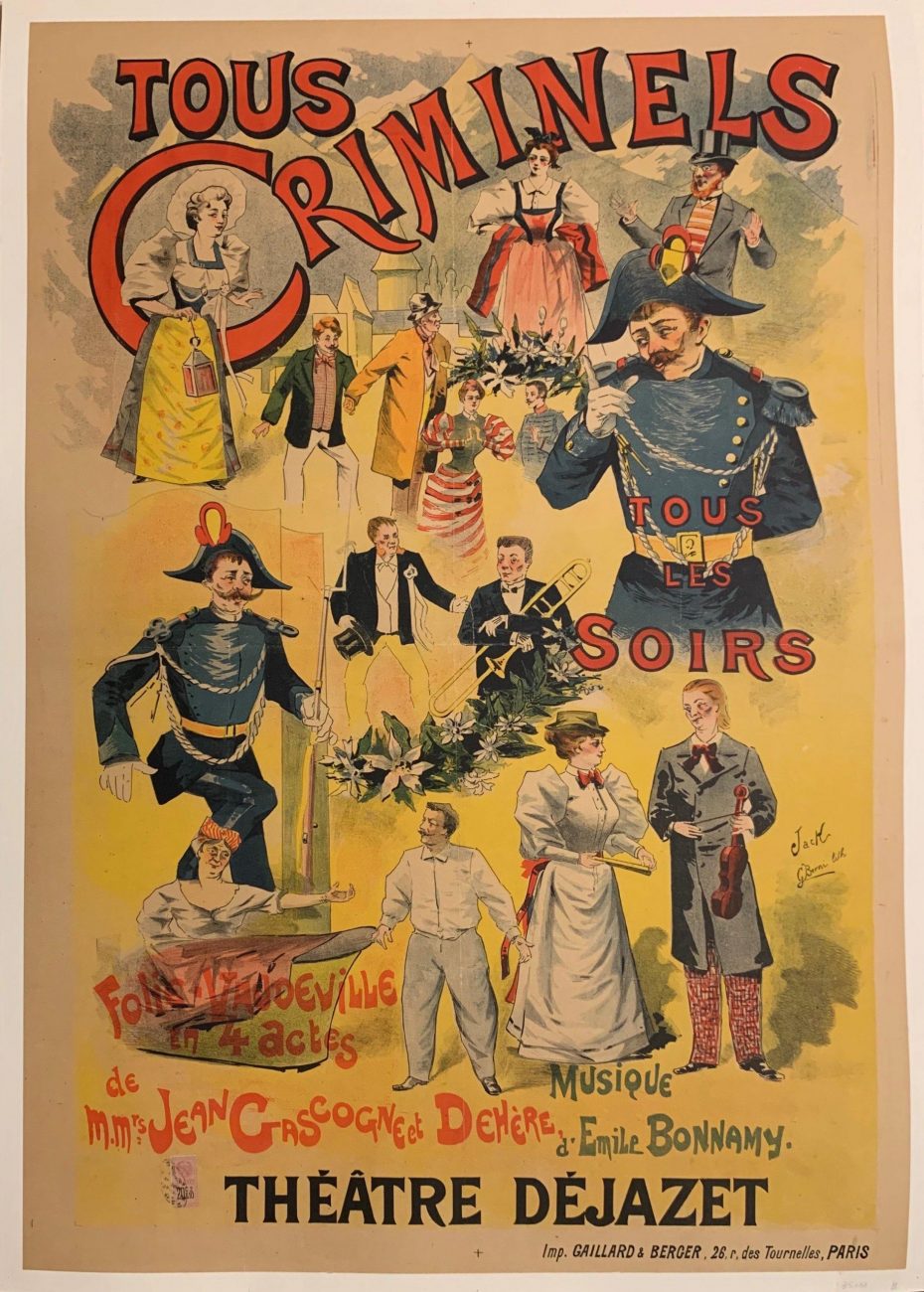

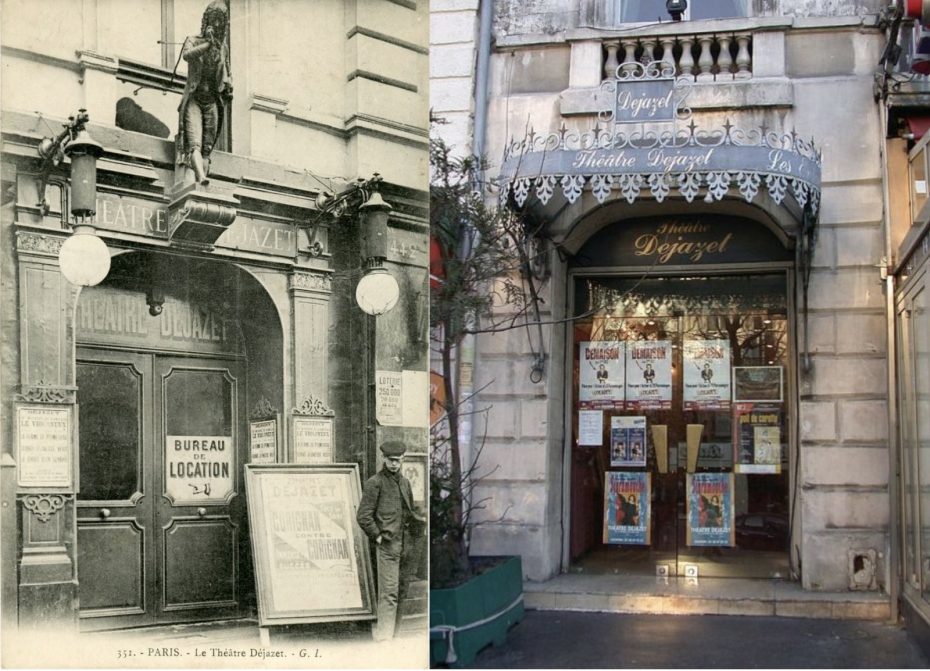

While many of the smaller theatres never reopened elsewhere, some of the larger companies found new homes, like Gaieté, which moved to the nearby Rue Papin and the Théâtre du Cirque, which became the well-known Théâtre du Châtelet. And as the architecture of Paris changed, so too did theatre styles, as melodramas gave way to operetta, a form of often humorous “light” opera, and more classical opera styles. To this day, one venue survived Haussmann’s retransformation in its original location: Théâtre Dejazet, which was founded in 1770 by Comte d’Artois.

Ironically, the only reason it was spared was because it was on the opposite side of the street. And the theatre has now survived another hurtle that could have struck the final blow – multiple closures due to the pandemic. Dejazet’s 85 year-old director Jean Bouquin, the son of an illiterate laundress and a former couturier to the stars, saved the building from being turned into a supermarket in 1976 and restored it to its former glory. After overcoming Covid-19, Bouquin now self-quarantines at the theatre, calling it home and spending upwards of 20 hours a day working to preserve and continue its history and that of Boulevard du Crime.

“Since 1770, this place has been a place of revolt; let’s make sure that it will always be, alongside the republic, the bread of the people,” Bouquin wrote on the theatre’s website. “I wish the Déjazet Theater, symbol of this Boulevard of Crime and ‘Children of Paradise,’ to remain the torch of hope for all those who strive to think that ‘the future is only youth’ and that nothing should weaken it.”