Even the most sheltered among us have heard horror stories of foster care and adoption, but back before there were arms of government to protect wards of the state, there were orphanages. And before orphanages, there was baby farming.

“Baby farming” was a term coined during the Victorian Era to describe the practice of taking custody of unwanted children or those whose parents were unable to care for them, for a small fee. Essentially, a baby farm was a for-profit orphanage. The practice of baby farming was most widespread in urban areas of late-Victorian Era England, but it was also prevalent in North America and Oceania.

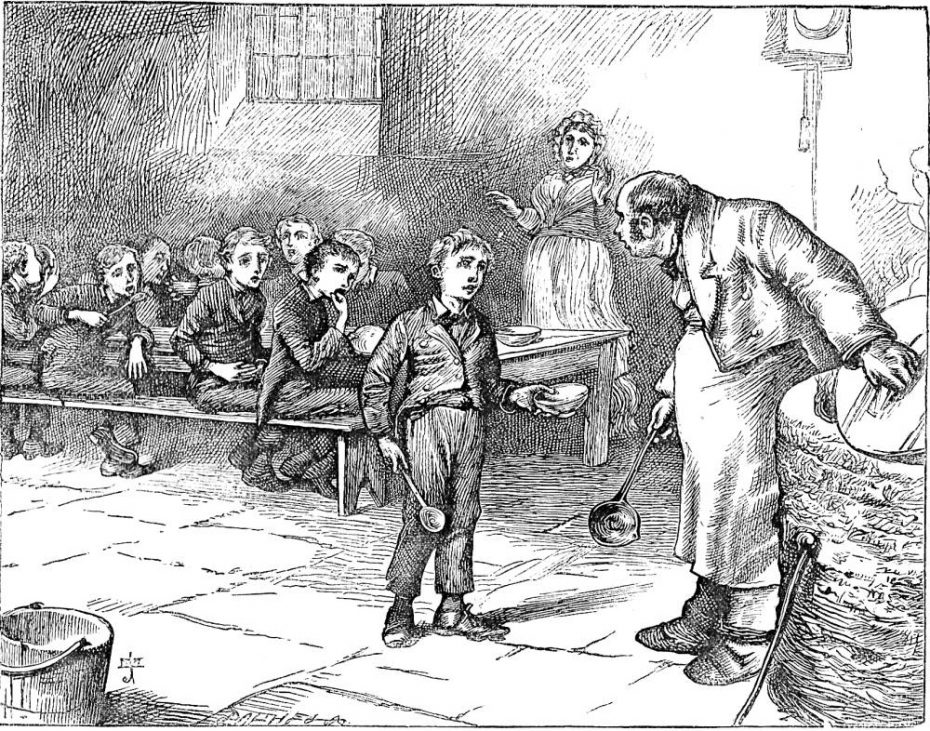

In an era when the most prevalent form of contraception was abortion, for working-class Victorian women who found themselves unable to care for a child, a less dangerous alternative was to surrender their newborn or, “put them out to nurse” at baby farms for a small weekly fee. Most women who chose this route assumed that their child would be properly cared for and receive a wet nurse, attention, room and board at the very least. After all, as referenced heavily in the writings of Jane Austen, wealthier women were also known to put their infants in the care of wet nurses – women who were not the childrens’ biological mothers, but who would breastfeed the children. The fictional character Grenouille of Perfume, as well as the titular character of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist were both residents of baby farms.

In 1834, The Poor Law Amendment Act allowed poor, unwed mothers to be given food, money, or clothing from the parish only if they went to live in the workhouse. According to the Ultimate History Project, because of the extremely dire conditions of work houses, “many of the women eligible for workhouse placement chose to place their children elsewhere so that they could continue to work and earn money – outside of the workhouse.”

One of the most common forms of employment for young women was in domestic service, but servants usually lived in their masters’ homes, which didn’t leave room for children. The wages they earned however, did allow them to send money to other women to raise the infants, and many of these self-named nurses or foster mothers did not regard themselves as “baby farmers”.

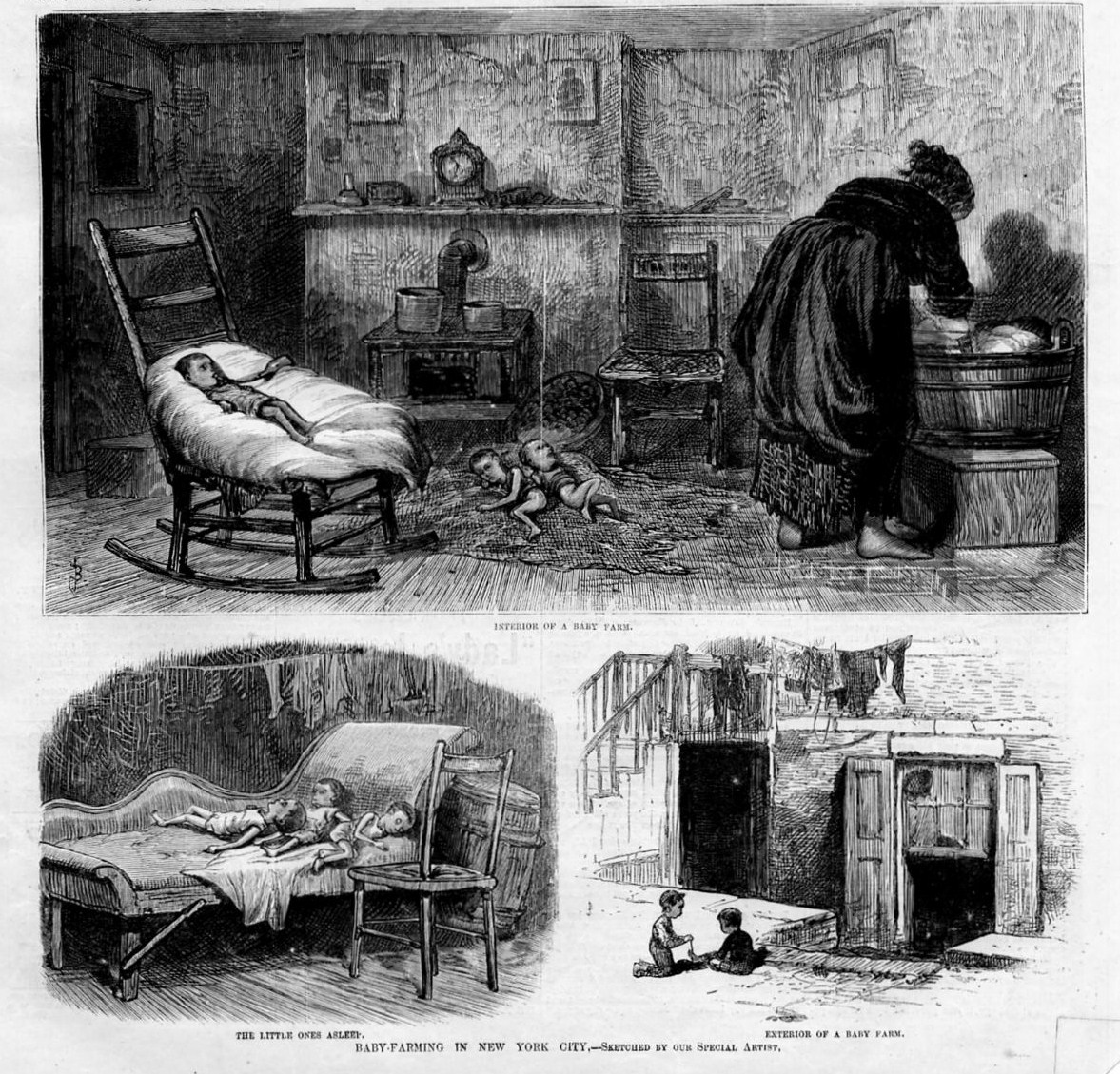

In theory, the system was working well: it was a sort of round-the-clock day care for working mothers. Ideally, the baby farm would be close to where the mother worked so she could visit often. In reality, very few children surrendered to baby farms would even survive their infancy.

Such tragedies occurred when carers – mostly women – started to exploit the business model. As a modus operandi, nurses would take in far more children than they could realistically care for in order to increase income. How could one maximize the profit? Take in more children and save on the cost of providing for them adequately. During the height of industrialization and urbanization, combined with stagnant wages, farms actively published advertisements seeking unwanted children to foster or “adopt”. Predominantly located in city centres, these were notoriously unhealthy places for children. They died rapidly from illness, malnutrition, neglect and abuse. Conditions grew so grim that even when a nurse was well intentioned, the child had a poor chance of living to adulthood. Most were sent away as soon as the mothers could leave the bed, substituting breastmilk for pitiful diets.

While some nurses required a weekly sum from the mother other more nefarious operations required up-front payments for taking in a child. Since these small lump-sum payments could not cover the care of the child for long, “the dangers of such an arrangement are obvious”, notes the Ultimate History Project, “but a young woman with an illegitimate child was often desperate to place the child and return to work.” With up-front payments and early infant deaths, baby farmers started to realise the arrangement could be more profitable for them if the infant or child they adopted died early, leaving room to house more vulnerable children and bringing in a constant supply of cash. This practice eventually led to one of the darkest pages in recent history.

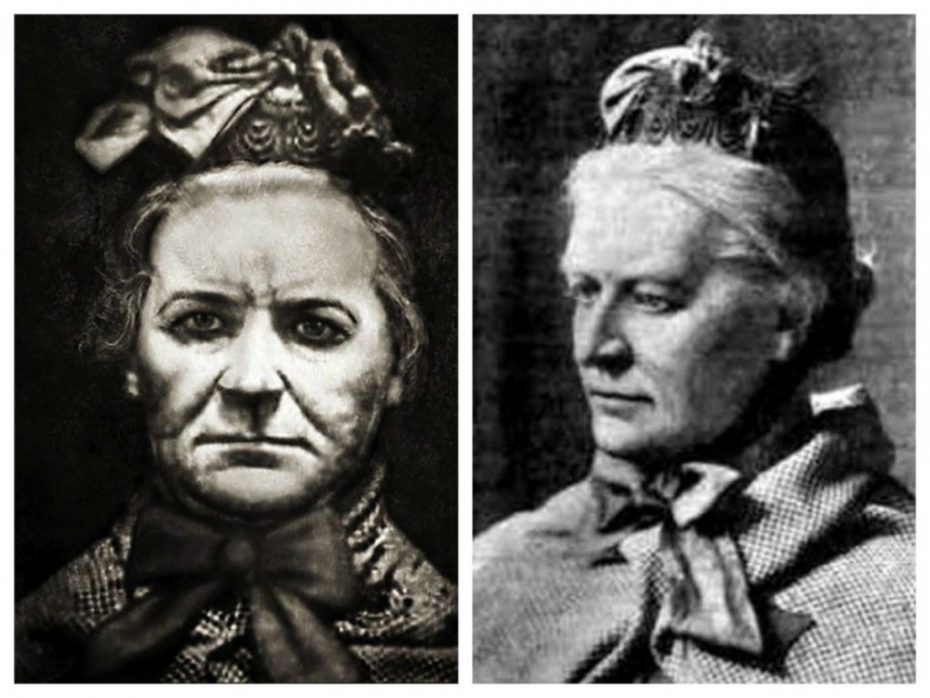

One of the most prolific serial killers in the world was a baby farmer. Amelia Dyer was a widow and trained nurse, and initially she cared for her charges legitimately. A number of them still died in her care, though, which led to a conviction of neglect and six months hard labor. It’s estimated that she took 400 lives in her baby farming business, strangling many of them and disposing of the bodies. One of the babies was discovered in the River Thames. She was convicted of the infant’s murder, and hanged.

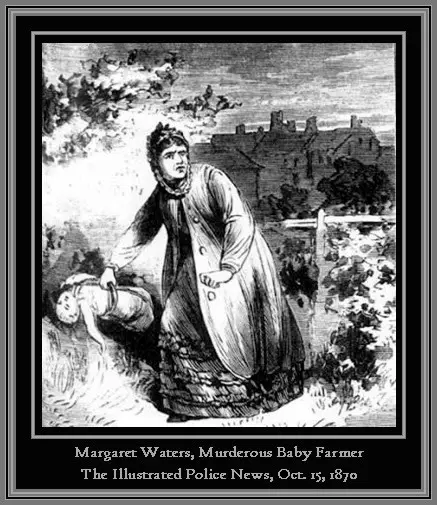

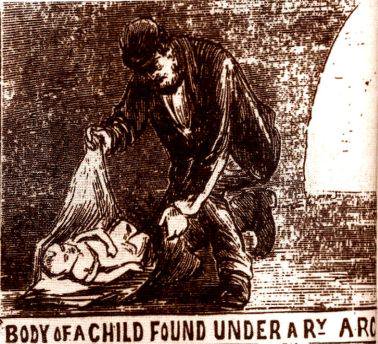

But Amelia Dyer was far from the only murderess that spawned from baby farming. Margaret Waters also disposed of the children in her care, but she came to realize that it was far easier to drug the babies with opiates, which suppressed their appetites and left them to slowly starve before dumping them on the street in brown paper – a sight that was not uncommon during those times due to the high cost of burials. Five babies died in her care, but she is suspected of murdering up to 19. She was eventually arrested, tried, and hanged for the murder of John Walter Cowen, the illegitimate son of 16-year-old Janet Tassie Cowen. Waters’s crimes lead to the establishment of the Infant Life Protection Act in 1872.

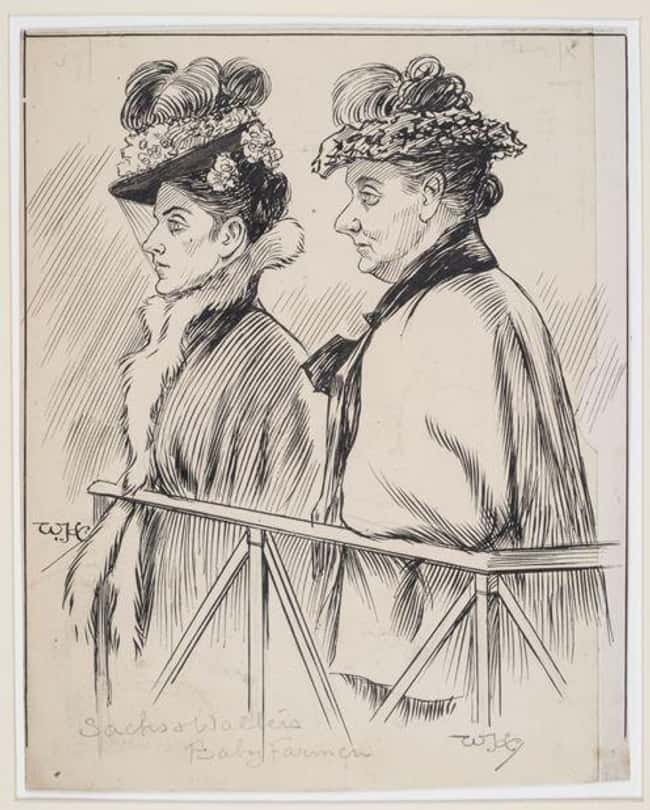

Researching “baby farms” will lead one quickly into the realm of female serial murderers. There was the midwife Amelia Sach, who helped women deliver babies, telling them she would find them homes with wealthy couples in exchange for money. Once in her care, Sach and her employee Annie Walters then poisoned the children with cholorodyne and dumped them in trash heaps or the River Thames.

Their landlord was a police officer who became suspicious when the babies Sach brought home would frequently disappeared. When Annie was arrested, she was holding one of her victims. She and Amelia were both convicted of murder and executed by hanging.

In New Zealand, Minnie Dean, the only woman to be executed in New Zealand’s history, Minnie Dean, was a baby farmer. In Scandinavia, these child murderers were commonly referred to as “änglamakerska“, literally meaning a female “angel maker”.

One might think – and hope – that this practice faded with the new protections for children, and it did fade, but not completely. In the 1930s in Nova Scotia, there was the case of William and Lila Young and the Butterbox Babies. They established a refuge for unmarried mothers, which they named the Ideal Maternity Home.

As described in Bette L. Cahill’s book Butterbox Babies, “within two weeks, the child would succumb and be finally laid to rest with white pine butter boxes standing in for coffins. Their tiny bodies would be either buried behind the Maternity Home property, in a field adjacent to a nearby cemetery, tossed into the sea, or burned in the home’s furnace.”

We weren’t quite expecting to discover that devastatingly, the term baby farming is still in use today to describe a similarly dark but different business model. Formally known as “child harvesting”, it refers to the systematic sale of human children, typically for adoption by families in the developed world where childless couples might be stigmatised, but sometimes for other purposes, including exploitation and trafficking for slave labor. Baby farms have been found in India, Nigeria, Guatemala, Thailand and Egypt. Save the Children is leading several campaigns to combat child trafficking through prevention, protection, and prosecution, working with communities, local organizations and civil society, and national governments to protect children from being exploited – and to help restore the dignity of children who have survived. In 2013, the United Nations passed a resolution designating July 30 as World Day Against Trafficking in Persons to raise awareness about the growing issue of human trafficking and the protection of victims and their rights.

You can learn more about how to help here.