You might not know her name, but a century ago, Irene Castle was the household name at the dawn of the Roaring Twenties. Historians consider her to be the first original flapper but in her lifetime, Irene wore many hats: dancer, model, actress, animal activist, and fashion trendsetter. She left an enormous influence on American culture, so as we enter our own Roaring Twenties (here’s hoping), let’s shine a spotlight on a forgotten icon that might just conjure some of that Jazz Age magic and put a spring back in our step.

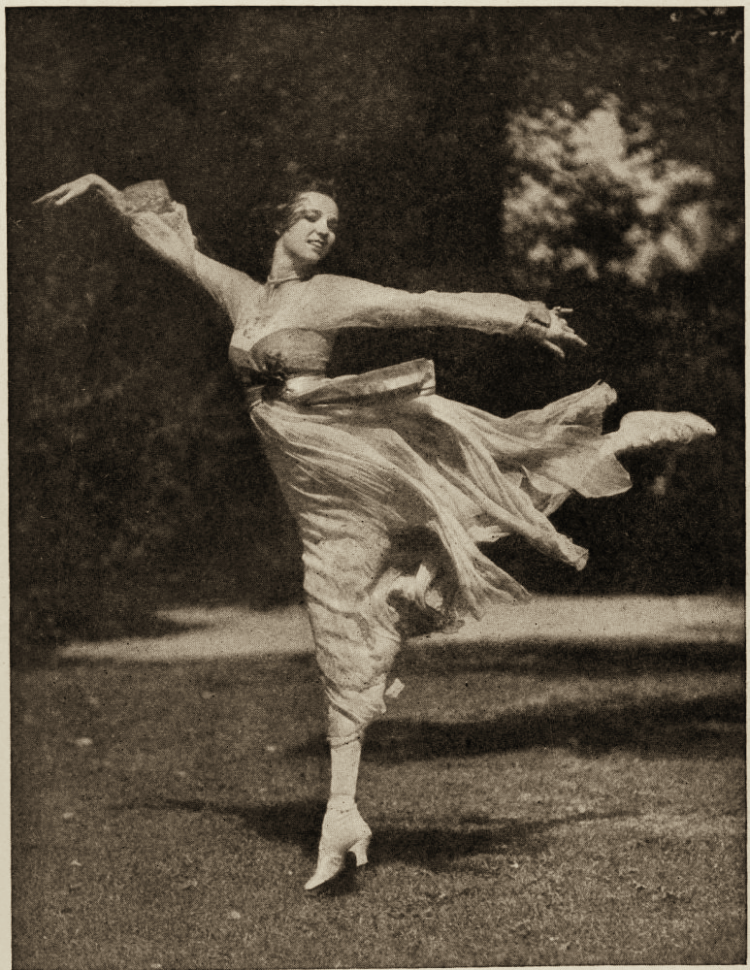

Irene Castle was born to dance. Growing up in New Rochelle, New York at the end of the 19th century, she had an affinity for the performing arts early on – she was always taking part in theatrical shows and dance recitals as a child and had aspirations to become a successful dancer. This dream came to fruition in 1910 when she met the man the would play an instrumental role in her life; Englishman Vernon Castle, an actor and an established vaudeville dancer.

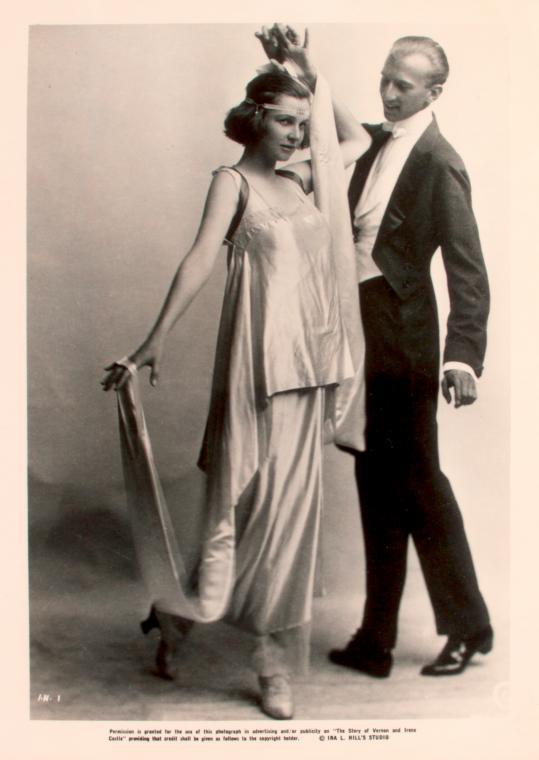

They quickly fell in love, got married and moved to Paris – naturally – where they were hired as professional dancers at the Café de Paris. The duo’s chemistry, elegance, charm, and quick feet enchanted their audience, and the couple began introducing the French to various types of American ragtime music. Irene and Vernon swiftly climbed the echelons of French society, and were soon invited to dance professionally all over Europe at exclusive social clubs and parties where old world ballroom dancing had been stuck in a bit of a funk.

Word of their celebrity status made its way back to America, and in 1912, Irene eagerly returned home with her husband, ready to make their mark on American society. They started out in a cramped apartment barely making ends meet, when they resumed their shows at an affiliate American branch of Café de Paris before becoming more in demand in vaudeville and on Broadway. They could not have chosen a better time to return to America; the country was discovering an energetic new musical genre known as jazz. The new dances that emerged, like the tango, favoured “close dancing” and were positively viewed by the younger generation, while for the older, conservative Christian crowds, it was considered provocative or more specifically, “the devil’s work”. American society now found itself at an ideological crossroads, and for those not so easily convinced, Irene and her husband created alternate versions of the provocative dances such as the handless tango. Irene and Vernon Castle also made many of their own dances like the Castle Walk, the Castle Lame Duck Waltz, and the Castle Half and Half.

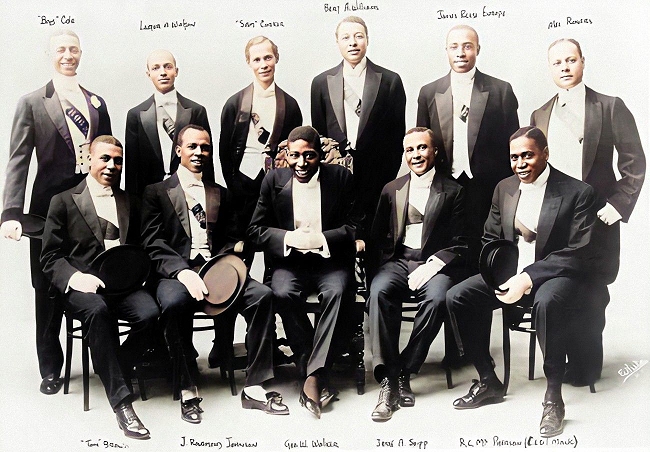

The Castle’s influential presence not only helped remove the stigmas surrounding close dancing, they were also simultaneously promoting African-American music to all-white groups. They travelled with an all-Black orchestra, believing that only Black musicians could do justice to the new musical rhythms of ballroom dance. But with segregation still a part of daily American life, they were faced with constant road blocks along the way. Slowly but surely, by introducing audiences to Black musicians through touring and persistently endorsing their phonograph records, together with the James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra, they broke barriers and became instrumental in launching the ballroom dances that would become the craze of the 1920s.

They popularised dances like the foxtrot, the waltz, the maxixe, the tango, and the bunny hug. They opened a dancing school across from Manhattan’s Ritz Hotel and their supper club, “Castles in the Air”, was located on a Broadway theatre’s roof. They also had a nightclub called “Castles by the Sea” on the Long Beach broadwalk and their own restaurant, the “Sans Souci”.

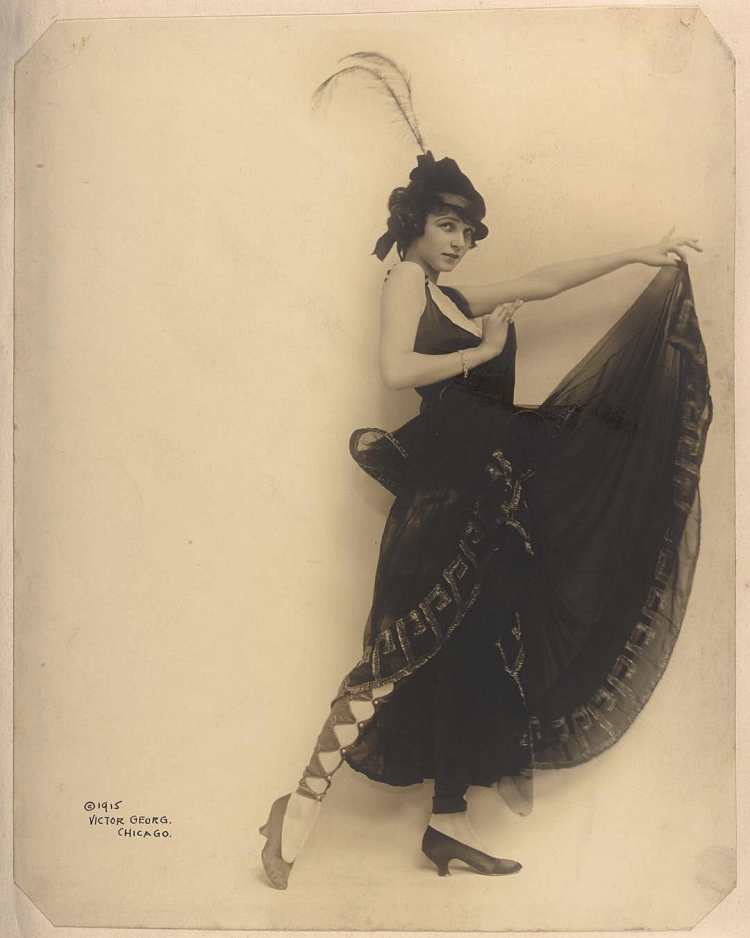

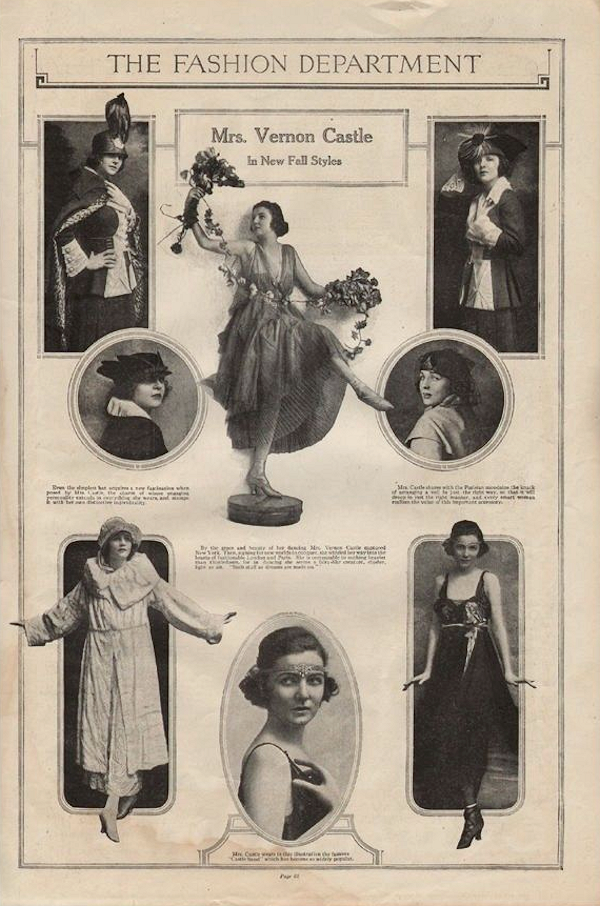

But the Castles, particularly Irene, did not just start trends on stage. She became a fashion trendsetter in every sense of the word, and came to be known as America’s Best Dressed Woman. What came after her was a fashion revolution – the perspective on style and dress changed completely.

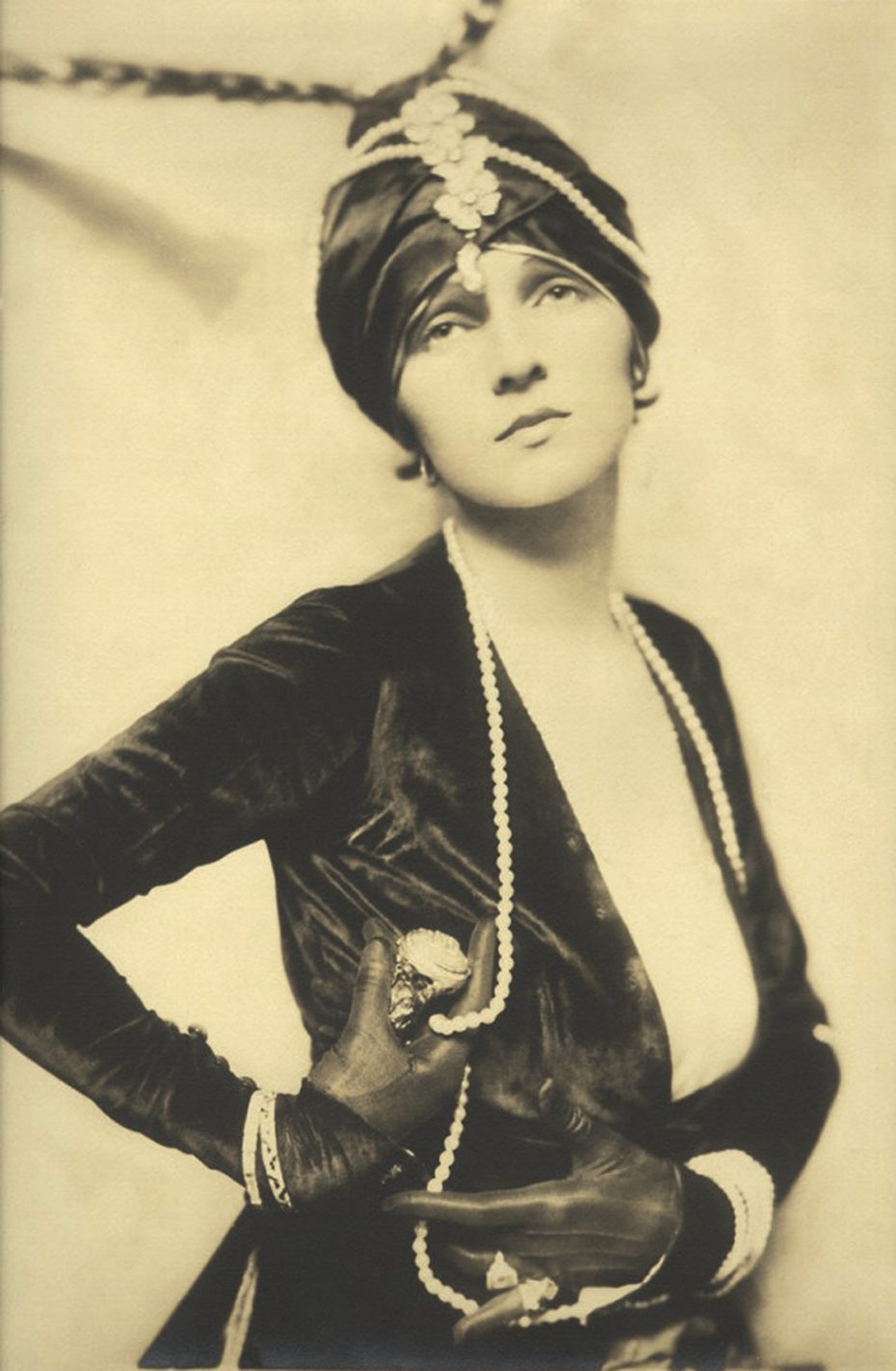

After finding that corsets restricted her ability to dance, Castle did away with wearing the traditional garment, opting to be free of corsets entirely or to wear elasticised ones. She started wearing shorter, fuller skirts and loose dresses. Castle also started wearing short bobbed hair, which many coined as the Castle Crop. This new trend was accidental, as Irene had cut her hair short to be more manageable after spending time in the hospital for surgery to remove her appendix. When she went out in public, she wore a pearl headband to keep her newly shortened hairdo in place. This headband became known as the Castle band, and women around America went crazy for it. Irene is even credited with what we would later know as the “flapper look,” which dominated much of the 1920s.

Tall, skinny, and sporting what many would consider a “tomboy-ish” appearance, suddenly Irene’s look was “in vogue” and fashion designers found her an ideal model to wear their creations. Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and other prestigious fashion magazines regularly featured Irene’s elegant, everyday outfits, many of which, were designed by her.

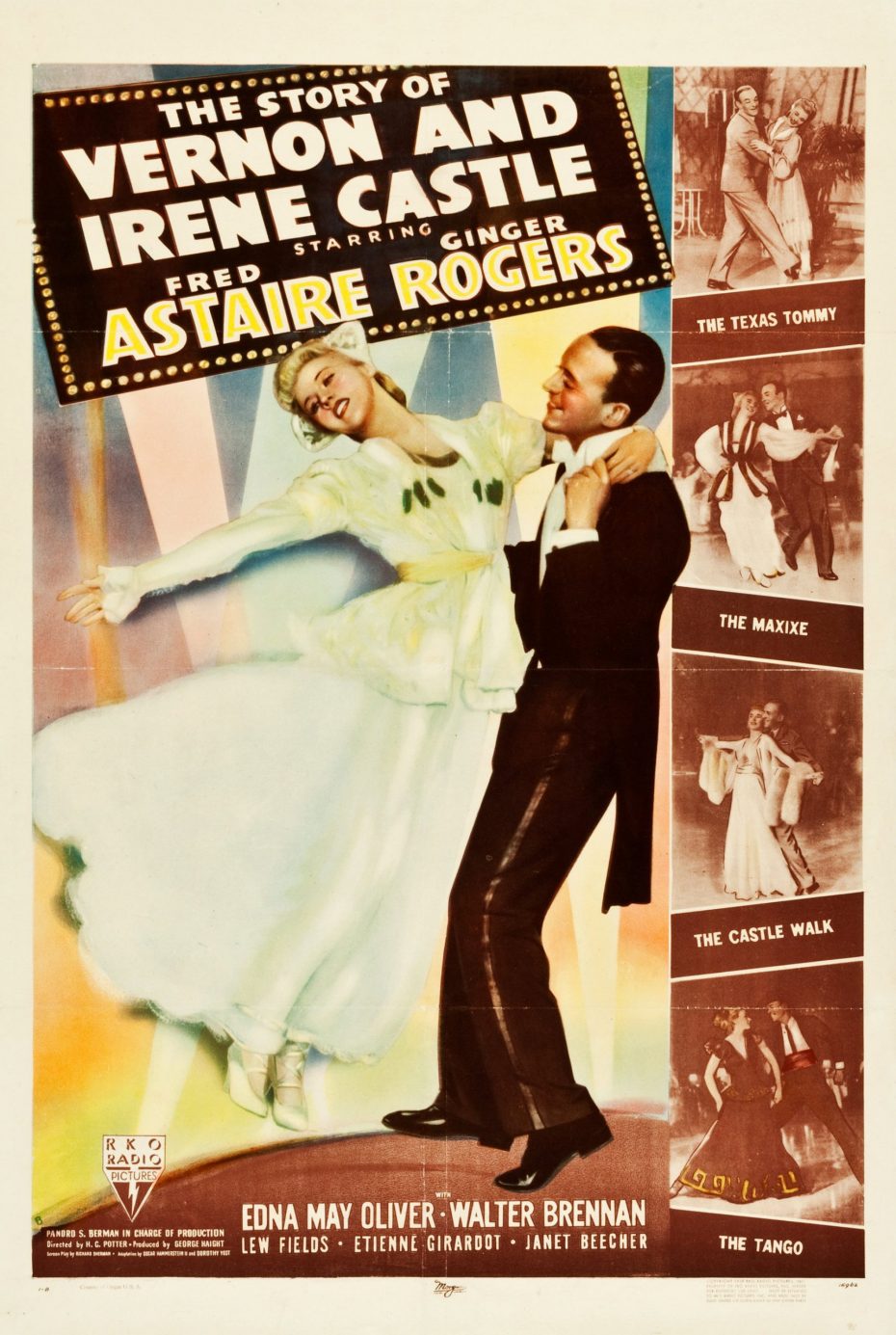

During World War I, Vernon Castle enlisted as a soldier for Great Britain and in her husband’s absence, Irene cut down on appearances to avoid having to dance solo. She couldn’t find similar chemistry with other dance partners and tragically, in 1918, Vernon Castle died in a plane crash while giving flight lessons to students. It was then that Irene Castle hung up her dancing shoes and transitioned into acting and modelling for magazines. From 1917 to 1922, she appeared in 18 silent films, most of which are considered lost. Some of her works include Convict 993, The Mysterious Client, and The Girl from Bohemia. Castle also worked to commemorate the love story between herself and her former husband in her the book My husband and served as technical advisor to the biopic film “The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle” which starred Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Irene would remarry three times in her later years, having children with her third husband, Frederic McLaughlin. During this time, she also became a dedicated animal rights activist, a passion that she carried until the end of her life. She founded the Illinois animal shelter “Orphans of the Storm,” which is still active today. Irene died of heart failure on January 25, 1969, on an Arkansas farm.

Her story has long been forgotten and most will never come to know the extent of her impact on American culture during the 1910s. Would history even know the “flapper era” of the 20s without the influence of Irene Castle? She defined several generations, introducing them to more diverse choices of dress and teaching them hundreds of new, modernised dance styles. And when nighttime venues finally get their chance to re-open, perhaps a new ballroom dance craze is just what we need to kickstart our joie de vivre in a post-pandemic world. All those in favour of a romantic ballroom dancing renaissance – say aye!