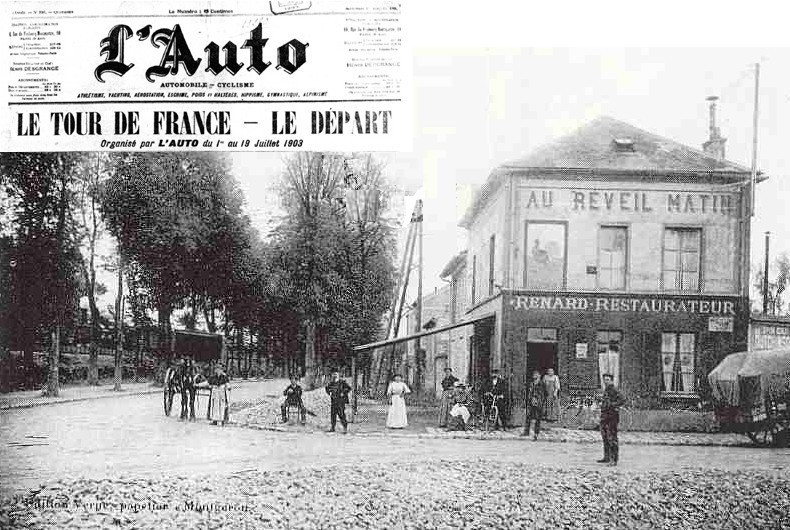

It’s 1st July 1903, we’re in Montgeron, a southeastern suburb of Paris positioned in front of the Reveil Matin café on the rue Jean-Jaurès. Excitement is in the air as 60 hopeful male cyclists line up at the starting line, eager to test their stamina in a new competition called the Tour de France. The line-up included a medley of mostly French riders, mixed with Belgians, Italians, Swiss and Germans hoping to peddle their way to the 20,000 francs prize money. Almost a third of the competitors were professionals backed by sponsorships deals, but the rest were merely men with a passion for cycling who hadn’t yet received the memo let’s say, on the magnitude of this new 1,500-mile race through France. Since the early 1900s, the Tour de France has gone on to evolve into a well-oiled media machine, pumped full of sponsorship, money, ambition and of course, its fair share of controversy along the way. Alpine climbs, new stages and regulations have all been added to the competition over the years but throughout it all and to this day, women have been largely kept on the sidelines.

Whilst the Tour de France grew in popularity from its inauguration in 1903, the idea of offering women their own competition seemed almost as preposterous as giving them the vote (France didn’t give women the vote until 1944). After the First World War, women did find a role in the competition however – as podium hostesses. In a post-war effort to lift spirts, the Tour de France organisers introduced podium hostesses to present the male riders with their prize, and if they were lucky, a peck on the cheek. This practise ended only recently, in 2020.

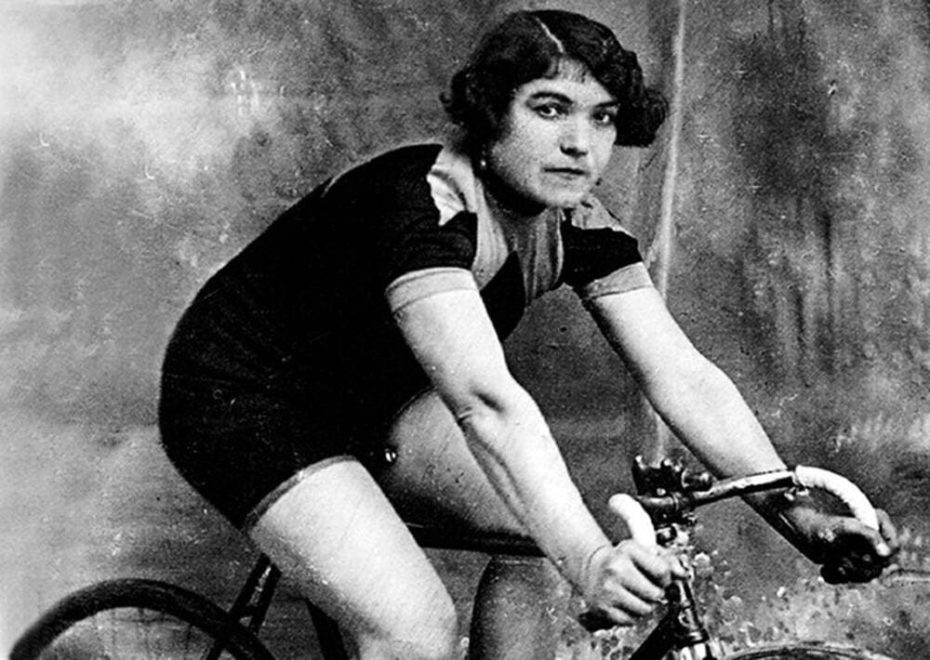

From its creation in 1903, it would take over 80 years for a women’s Tour de France to be put into place, and even then, it was very short-lived. That’s certainly not to say that women weren’t behind the scenes fighting to be able to compete. In 1924, Alfonsina Strada registered for the Giro d’Italia (Italy’s grand tour) with the sexually ambiguous name of Alfonsin. Duping organisers into letting her compete against the other male riders, Alfonsina completed the first two stages of the race before coming a cropper in Naples during a storm. Whilst she missed the time limit for this section, Alfonsina was allowed to continue, battling through many further falls and flat tyres. At one point when her handlebars broke she used a broomstick to fix them.

Alfonsina became a national hero. As she rode into Fiume for the 10th stage of the race, crying and hurt, the crowd lifted her from her bike, cheering. Alfonsina went on to finish the race, beating two men to the finish line, and making up the one third of the 90 competitors who managed to finish.

Fast-forward to 1984 and thanks to the persuasive powers of Félix Lévitan, at the time joint-organiser of the Tour de France, the Tour de France féminin was given the green light. Whilst 170 men jostled their way to the finish line, the women’s competition only allowed 36 riders to take part. Whilst the women were allocated a shortened version of the same routes as the men, meaning they finished around two hours before their male counterparts, they received no special treatment – far from it in fact. One competitor Deborah Shumway recalled how she was picked up from one stage of the race only to be driven to her hotel in a delivery truck filled with sandwiches.

As the Tour de France féminin got going, the Dutch team had the bookies’ votes, with the favourite Heleen Hage proving to be the safest bet. However, it was the American team that soon gathered the most attention, in particular Marianne Martin. Born in 1957 in Fenton, Michigan, Martin turned to cycling whilst she was in college, after suffering a running related injury. Gradually, she became more and more devoted to the sport and despite the lack of competitions available to her, Marianne would compete when and where she could. In her first national race, the Tour of Texas she won the opening time trial, which opened up new opportunities for her in the world of cycling, notably with the Tour de France’s US team. Despite missing out on a place for the 1984 Olympics, Marianne was destined for another competition that year and managed to secure the final place on the team.

Not everyone was convinced by there being a new female version of the Tour de France, notably certain members of the French press who gave negative reviews of the competition, proclaiming that no woman would even manage to finish the gruelling race. The winner of the 1983 Tour de France, Laurent Fignon declared, “I like women, but I prefer to see them doing something else.”

As Marianne began to do well in the race however, the table started to turn. It was one thing for a women’s race to even take place, but for an American to win? As the women’s race got into its 12th stage and Marianne was up at the front, The New York Times ran its first story on the event. The attitude had begun to change and the crowds who had come for the male athletes, now cheered on the women who passed before them.

Marianne took the yellow jersey in the 14th stage, signalling her lead ahead of the Dutch team and her fellow American, Deborah Shumway. For the final 30km of the race, Marianne maintained her lead, gliding into Paris through the Champs Élysées and ending the race under the Arc de Triomphe. The other women followed, with all but one finishing the race.

Marianne took to the podium alongside Laurent Fignon, the very man who had said he’d prefer women to be doing something else. While Fignon received $225,000 prize money, Marianne however would go home with $1,000 which she later said was shared with her team and used for her flight to back to New York.

The historic images of a man and woman standing side by side on the winner’s podium were beamed across the world but sadly the occasion was soon overshadowed by the Olympics which were held in Los Angeles in the same year. The Tour de France Féminin struggled on for another couple of years but due to lack of funding and enthusiasm the competition came to an end in 1989. With small event viewership, sponsors no longer wanted to support the event. No sponsors means no event. The race was then rebranded over the years to eventually become La Grande Boucle in 1998, but gradually the stages and number of riders were cut and the competition lost traction again.

Cycling as a sport has (unfortunately) yet to move past the common, sexist arguments made against female athletes – that women are not as strong as men and they don’t bring in the same amount of revenue as male athletes. But finally some good news. Women are getting another chance to compete at the Tour de France, as organiser Christian Prudhomme has confirmed an official women’s competition relaunching in 2022 stating that, “The challenge is to set up a race that can live for 100 years. That’s why we want it to follow the men’s Tour, so that the majority of the channels which broadcast the men’s Tour will cover it as well.”

We’ll be waiting at the finish line.