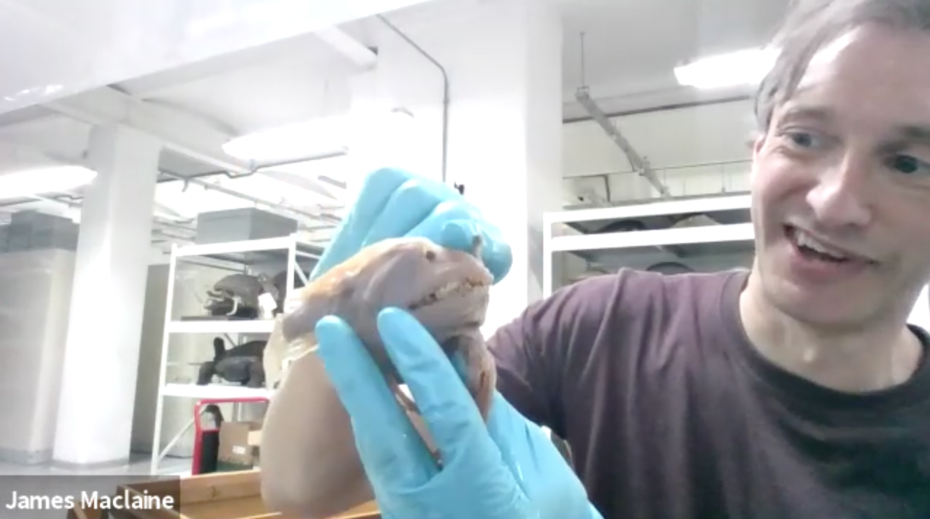

James Maclaine has been working at the Natural History Museum in London since the late 90s. He pretty much had the whole place to himself during the lockdowns, caring for thousands of specimens including the museum’s mind-boggling collection of pickle jars, some of which contain creatures that date to the voyages of Charles Darwin. We were lucky enough to catch up with James, senior curator, for a little Q & A and behind the scenes show & tell at the museum…

If you missed this Live Q&A, you can re-watch all the wonderful moments in the full Video Event here in the Keyholder Vault. In the meantime, we’ve transcribed some of the best questions below to whet your appetite…And just a little disclaimer: some parts have been edited for readability.

Messy Nessy Chic: I’ve got James here with us…and he’s coming to us live from the Natural History Museum in London. He just told me that he’s actually in the room underneath the main hall, and James, you were there during all the lockdowns and all that. Do you want to just start out by saying, because we’re coming out of lockdowns, what that was like for you?

James MacLaine: Yeah, I was really lucky because I was able to make quite a good case to keep coming in. I live about 15 minutes away by bike so I could travel in safely. There are certain duties I have as well as looking after the fish collection, which involve quite a lot of regular inspections. We get through about 3, 000 to 4, 000 litres of ethanol every year for preservation and we have this elaborate system where we have two big tanks full of alcohol. It’s pumped all the way around the building, so you can actually have alcohol coming out of a tap in some of the laboratories. That’s great when it works, but of course, if there’s any chance of a leak or anything, that could be quite drastic. So I was going around checking everything was working properly. [I was] checking the collection spaces as well because we’ve got one building that’s got 8 floors full of things preserved in ethanol, and again, we don’t want anything leaking. We want to make sure everything’s ok.

[I was] also going through the dry collections too. So, the room I’m in at the moment (there’s actually a book about it called Dry Store Room No. 1) where we keep a lot of the dried materials. So, things like this stuffed and mounted fish here:

And these have different sort of problems associated with them – the big issue here is insect pests. We don’t want any moths getting in and eating things, and there’s actually a beetle called the “museum beetle” that will nibble away at things. So, you’ve got to keep an eye on your collection at all times. Luckily, because I was quite close by, I was able to say, well, I can come in and keep an eye on things, and it was great. I had the whole place to myself pretty much and, yeah, it was actually quite fun.

MNC: So, it was sort of the real life “Night at the Museum“

JM: Well, yeah, I could just stand in the middle of [the big hall] and sing if I wanted to and nobody would know. It was really great. I was really lucky, obviously. Loads of other people were having a terrible time. The pandemic was quite good for me in a way.

MNC: I guess, my next question is, how did you get this job? Your official title is “Senior Fish Curator”?

JM: What am I now… I guess I am a senior curator in the fish section. Or “Senior Curator (fishes)” – something like that.

MNC: So, how did you get this job?

JM: I’ve always been interested in fish and I did a degree in Glasgow, Scotland, way back in the early 90s. After that, I had a fantastic job where I was working on the River Tweed in Scotland. We were tagging salmon as they came into the river, so we’d net them as they came into the river and put these radio transmitters inside them. Then I had a Jeep with an aerial on top and I’d spend my days driving around the Scottish borders up and down the river trying to find where all the salmon had gone. That was a fantastic job, I really loved that, but it was just a 3 year contract. And then after that I was sort of in the employment wilderness a bit, and I ended up working as a temp in a bank and I wasn’t really enjoying it very much. My mum suggested, “well, why don’t you get in touch with the Royal Museum of Scotland? You’ve loved it ever since you were a little boy and just see if they need any volunteers or anything.” So, I thought, it’s worth a go. I got in touch with them back in 1998 and I had no idea about the collection side of the museum. I just mainly was aware of the public exhibits and things. It was a great surprise to me when they said “yeah, we’d like to employ you as a volunteer and then put you behind the scenes curating things, and working with spirit specimens and looking after material that’s sort of tucked away in cupboards.” So, that was my first experience of that, and I really enjoyed that a lot. And that gave me just enough experience to get an interview for here. I never in my wildest dreams thought I’d be here in the Natural History Museum in London. And when the interview came up, I thought, well I’ll go for it just for the experience, and one of the interviewers took a shining to me for some reason and here I am twenty years later. So, yeah, very lucky.

MNC: So, it really all just started with volunteering, which seems so … doable.

JM: Yeah. I mean, it’s really sad in a way that that’s the sort of state of affairs now and that we can’t have more paid internships and things like that, but yeah, nowadays we still rely on volunteers very heavily. I have a team of four or five that come in and help with things and I wouldn’t be able to do my job without them. I think they’re a fantastic resource and sadly that, if you want to get experience now, that’s probably the best way to do it.

MNC: I mean, weekends I guess? It makes me want to volunteer at the museums that I love here in Paris now. Maybe I might be able to see more backstage.

James: Well, it’s something that’s getting more and more common and they have the sort of citizen science programmes and things where they can put lots of data online and then people can actually work on it in their own homes and look for things [like] mistakes, and you know, lots of people really just love getting involved with museums.

MNC: Obviously COVID was very different for you, but to give us a better idea of your working day, on average, can you tell us what you did yesterday, for example?

JM: I was at home yesterday, but today… What have I done today? I came in and my first job was [to] do a little bit of a tour round, make sure there’s nothing bad that I can see. Nothing leaking, no cracked jars or anything like that. And then, one of my first duties is to check on the beetle colony. One of the collections we have here is a collection of skeletons. Skeletons can be really interesting. We occasionally have archeologists who come in because they’ve found a strange bone and they want to match it up to something. So, we use our skeleton collection quite a lot, and if we have extra fish or other animals, we skeletonise them. And one of the ways we do it, is we have these three boxes full of these beetles. I mentioned the problems of museum beetles before, but in a contained environment it can be really useful. So, we have these three boxes and you just put a dead fish in a box, and then two weeks later you have a nice clean skeleton because the beetles have nibbled away at it. But of course, they weren’t really getting a regular supply of food over lockdown, so they nearly died out, but I went to my local fishmonger, and I bought some bits and fed them to the beetles. Managed to keep them going. So I’m still looking after them. And they need to be kept damp, so I have a water misting thing and I have to give them a little spray in the morning, keep them happy.

So, I did that…and then I went looking for a specimen that we were supposed to have but we couldn’t find it before. And I did managed to find it. It was wrongly filed! The other thing about my job is that you start doing one thing, and then you find three other things. So, when I opened the cupboard looking for the missing thing, I then found something where the alcohol was evaporating so I had to sort that out. And then, I had to update the digital records for them. Then, this afternoon, I’ve been going through lots of boxes. We’re clearing out the store room in South London [so we’re] just going through them, finding what’s in them, and it’s a real mixed bag. I mean, there’s some really lovely things like this:

This is a model of an anglerfish from our old fish galleries. We used to have a really lovely fish gallery that got turned into, I think, human biology (sadly) and all the fish that were on display in that gallery have obviously had to be packed away in boxes… hopefully we’ll be able to use them for other displays in the future. Other things [are] not so fun – [there’s] some really horrible old dried fish in this box here:

But kind of interesting historically [as they] were collected in the 1870s I think in India, so they might be useful. So, I’m just cataloguing everything and just finding out what we’ve got in these boxes. But every day is different really.

MNC: So discovering new species aside, you’re also discovering old archives constantly as well?

JM: Oh yeah. The historical side is almost as important as the science side I think because [in] our fish collections… I think the earliest thing we have is possibly from the 1730s. That’s not been proven, but then we do have things that were definitely collected in the late 1700s and then all the way through the Victorian era up to the present day. It’s a really old collection in parts and because of that it’s interesting from the people who collected it. Some of the 1770s fish specimens were collected on the Captain Cook expedition, so that’s kind of nice, and we’ve got things that were collected by Charles Darwin and still have his little handwritten labels on their tails, so there’s often a historical side to something as well as the scientific side.

MNC: Absolutely. And on the scientific side, how often do you find yourselves discovering, studying, and labelling new species that come in?

JM: I’m much more of a caretaker than a scientist myself, but I do help a lot of scientists. I basically know a lot about lots and lots of things, but none of those things in great detail. I know loads of people as well because I’ve been working at this job for twenty years, so I have all these amazing connections. What I’m quite good at, is finding something and knowing it’s different, and then knowing who to send it to. [For example,] we have an amazing collection of deep sea fishes that we collected in the 1960s and 70s. Me and a couple of volunteers have been sorting through them, and occasionally we’ll come across something that we can’t find in any of the reference books and it looks different. What we will then do is send it on to somebody else in most cases, and then they will say this is actually a new species, and that’s as involved as I get normally.

Keyholder: Do you wander the museum poking into all the collections and exhibits?

James: Yeah. The museum’s a great place, and not just in the exhibits, but behind the scenes as well. There’s lots of bits that are very modern, and then you’ll go through a door and it’s like you’ve gone back to Victorian times. It’s this weird mixture of the old museum and the new museum. And it’s a real labyrinth underneath – I still get confused and can’t work out where I am. They’ve just renovated the upper levels of the central hall as well and that is just gorgeous – in there they’ve got all these birds suspended from the ceiling. They’ve done a really beautiful job. I like rummaging around in rooms like the one where I am now, and going through cupboards and things…and there’s always a surprise [where] there’s just some old dusty label that when you read it properly you suddenly go, “oh wow, that was from this expedition.” I haven’t got bored working here yet.

MNC: With the behind scenes side of things, how often does your team get new specimens in, and also, how and who is collecting them?

JM: It’s a complete mixture, because for example, the big blue marlin that I mentioned… was found by some people walking their dog on the beach. That was washed up on a beach in Wales and we just got this call one day that this enormous swordfish has been washed up. We had to drive to Wales with a van and then put it in the back of the van and bring it back. So we get fish from members of the public. Fishermen who catch something interesting love the idea of it being on display in a museum, so we get interesting fish caught by anglers, but we also do go on expeditions. I was really lucky to go on a cruise to the south Atlantic a couple of years ago. We did lots of sampling around Tristan da Cunha and St Helena and brought back, I think it was nearly 2, 000 fishes, [and] lots of other things as well – lots of molluscs and invertebrates. That was a huge collection that we made there. We also have researchers who go off in various places. So we have new stuff coming in all the time. It’s definitely an active, growing collection that we have here.

Keyholder: Have any of the more recent sensitivities to decolonising museum collections affected your museum? If so, how?

JM: That’s something we’re taking very, very seriously and we’re looking into different ways of doing that. It’s something we’ve got to be really aware of. I mean, this fish here was collected in Australia, when that continent was being colonised and people were going there and taking the land and everything. There were also scientists who were going there and collecting things at the same time. So colonisation and collecting go hand in hand. We have huge collections from India and Africa which were taken from parts of the old British Empire when we were there. So, we have to, at the very least, acknowledge that and say that we wouldn’t have got a lot of this stuff if we hadn’t basically gone there and just taken it. The Victorians in particular just thought that the world was theirs to do with as they pleased, and [that] they had this divine right to go there, take over some place, and take what they wanted. And so we need to acknowledge that. We need to say, “these things, we got these because basically, we invaded somebody else’s country.” I think that’s the start and we definitely have to be very public about that and start to speak about that more and also to show the other side of the collecting story too. Because, again, this was collected by a guy called John Gilbert, and he was on a team which also had aborigines who were helping collecting. So we need to tell those other stories too, not just about the white men who went out there who were maybe in charge of the expedition, but also the local people who helped out and maybe did most of the actual collecting. That’s very important.

MNC: How often do you remove and handle the specimens?

JM: The Captain Cook ones, I think they’re some of the oldest pickled ones that we have. They still look pretty good. As long as they’ve been preserved properly, they should be fine. They tend to fade over time and that’s why we try to keep them locked away in dark cupboards, because if they get any exposure to sunlight they can just go completely white, so that’s the biggest problem. A lot of them look very pale, like a pale beigey colour, but apart from that they keep their structure pretty good.

You can take them out of the jar pretty much whenever you like as long as they’ve been nicely preserved. They’re usually pretty robust. So, this is a fantastic specimen (above) I love this specimen. This is a kind of deep sea anglerfish called a “leftvent sea devil” and this is a female specimen. She’s got this beautiful beard here, which I believe, when she’s alive, is covered in lights. She also has a little matchstick coming out of the front of her nose, and that’s a light organ as well. That would glow, and she uses that to attract her food. So she sits there in the dark, kilometres down in the sea, and wiggles that around and things come over to have a look and then they get gobbled up.

They have this really weird thing where they’re, what we call, sexually dimorphic. The females are quite big and they have the light organs, and they have the teeth and the nice beards and what have you, but the males have got very reduced. They’re just like little tadpoles [with] big nostrils and that’s how they find the females. They [then] attach themselves, and in some cases, permanently. That’s her little deep sea husband there. As you can see, I’ve taken that out of the jar and it’s a little bit floppy but it’s fine, and that’s probably about 50/60 years old that specimen.

MNC: What does it smell like?

JM: If there’s any kind of bad smell, it means that someone hasn’t done their job properly, because there shouldn’t be any kind of rotten smell at all. Occasionally, if it’s something that’s been quite newly preserved, there’s a little bit of a fishy odour because sometimes oil comes out of the specimens a little bit and that makes a sort of fishy smell, but nothing too offensive. And some of the really old ones that were pickled way back in the early 1800s, have actually got quite a nice kind of, almost like a Christmas pudding kind of smell, because they used to make ethanol by distilling wine. They used to call it “spirits of wine” and so some of it has almost like a brandy-like smell to it. So, no bad smells. The only time we have bad smells is if something goes wrong with one of our freezers. We often have things that we can’t immediately process and they go into the freezer so we can deal with them. We did have one time where a freezer got accidentally turned off, and that was a very, very, very bad smell.

MNC: I wanted to know, why are so many specimens not on display? And not just in your museum, but in so many museums. Why is so much of it behind the scenes? Is that something that might change? or is it a question of space? Or…?

JM: It’s a combination of a few things.

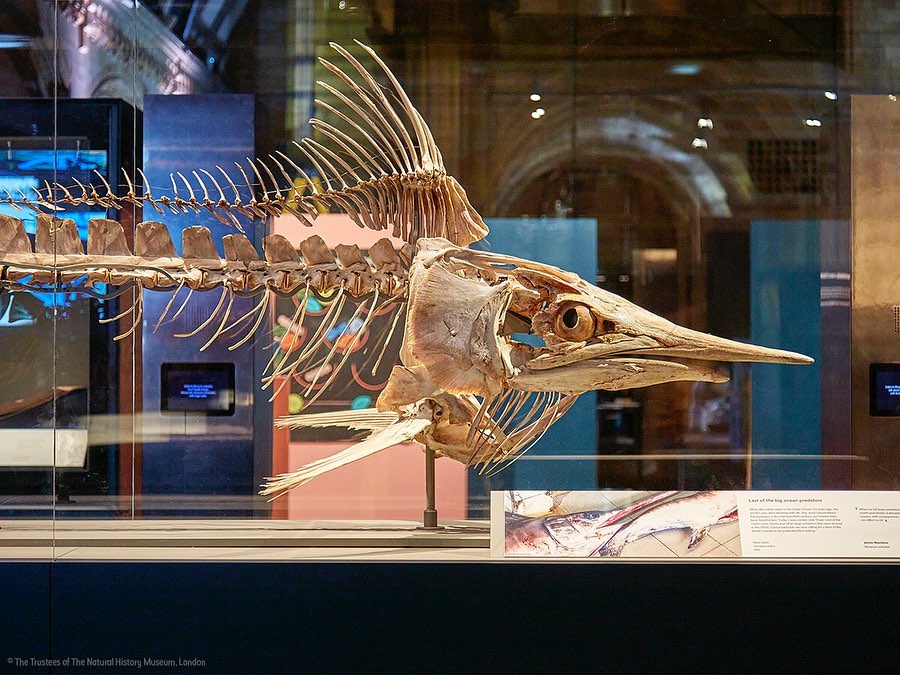

Firstly, I think, just the sheer volume of stuff. We couldn’t put it all on display. For fish alone, we have hundreds of thousands of jars and if you added up all the individual fish it would probably be close to a million we’ve estimated. So, there’s an awful lot of material. But, we do try now. In the past, there was a move towards having models – a bit like some of the things I’ve been showing you earlier. But now, for newer exhibitions we always try and use specimens if we can. So we’ve just opened up a new exhibition called “Our Broken Planet” which is about how people are affecting the planet and how it can do things to change that. And we’ve put a huge marlin skeleton there. I think that’s over 3 meters long and that’s really impressive. A model can be more beautiful looking than a specimen, but I think people love to see the actual thing.

But another thing is the building where I spend a lot of my time, which is called the Darwin Centre, which is off to the left of the museum if you’re facing it. One of the main ideas behind it is to give people a chance to go behind the scenes and to go into the store rooms and see the specimens. So if you go into the ground floor of the Darwin Centre you can see through all these glass windows into a collection store and see everything all laid out and then you can do an actual tour that goes through the building and goes into the big room in the basement where we have a giant squid and some other really big pickled things. So we’re trying to open it up and give people a chance to see the collection side of things behind the scenes, which I think is great and people love it.

MNC: A Keyholder asked, “Does the museum ever offer behind the scenes tours?” So that’s a yes?

James: Yes, it does. And they’re really good. I know quite a few of the guides who do the tours and they’re excellent.

Keyholder: Who decides what goes on display?

JM: That’s a bit of a conversation really. Another part of my job I really enjoy doing, is when an an idea [for an exhibition] comes along, one of the first things that will happen is, the exhibition designers will get in touch with us and say, “ok, we’re going to have an exhibition about Antarctica, what would you like to put in it?” And then we can go, “well, we’ve got these ice fish specimens. That’s an interesting story” and then they will go away and do some research and say, “ok, that’s a really good idea. We’re not going to use that.” So, they have an idea and they come to us and we suggest things, and then between us we work out what would work well and take it from there really. It’s always fun doing that. I always push to get as many fish in as I can. I think my absolute favourite for that was, we had a fantastic exhibition back in, I think it was 2010, called “Sexual Nature” which was all about weird mating strategies that some animals do. We got a lot of fish stuff in there, including the anglerfish with the female and the tiny little male. Get that into everything.

MNC: Do you have a favourite specimen in the collection?

JM: I think it probably…another anglerfish which is a bit bigger and it’s even more hideous, as you can imagine. It’s called a football fish and it’s about the size of a football. It’s a sort of big, brown, leathery round thing, covered in little spikes and again, it’s got a thing on its forehead which looks like a little branch with lots of little tendrils. And that fish just brings so much joy to people. We occasionally do evening events where we get out a few things of interest and people just love the football fish. They really do. And they love the story of the fact that the female is the football size thing and the male is just this tiny little blob and yeah, I love it because it looks weird and it’s got an interesting story and I also just love the fact that it’s a great way of educating people and entertaining people at the same time.

MNC: Can you also tell us a little bit about how changes in technology over time have influenced the way researchers are using the collection?

JM: Yeah. The most obvious one is DNA. I don’t know when they first started using that, but it really became an issue from the 90s onwards. Before that time, like these horrible crispy things that I showed you before, somebody would have thought, well, they have no value whatsoever. But now of course, you can get DNA from them and you can tell a lot. I heard a fantastic thing, on another podcast recently, about how they could tell from DNA of a fish, what kind of flavours it could sense, and there was like a set of genes for like, detecting sourness. They could tell what taste organs this fish had in its mouth by looking at its genome. And stuff like that, nobody in their wildest dreams thought you’d be able to do that a few years ago. And then there was the other thing I mentioned briefly about isotopes, where, as an animal passes through an environment, it absorbs isotopes from what it’s eating and what it’s accumulating as it goes through. You can actually tell what regions of the planet things have either lived in or passed through by the way that isotopes are deposited in their bones. That’s exciting.

And then, with regards to things like imaging, there’s so many great things you can do nowadays. I think the whole CT scanning thing I find really exciting. This is where you basically get a specimen and you make a three-dimensional digital X-ray of it. You can then just copy the whole thing and have it on your computer screen -you can rotate it, zoom in on it, strip away all the flesh and just look at the skeleton, and you can see inside it. So you can digitally dissect something and if there’s a bone you’re really interested in, you can just cut it out in your computer screen. And then, if you really want to examine it properly, you can then 3D print a plastic copy of the bit you’re interested in. That’s really amazing and that’s just going to get better and better, I think.

MNC: In this very fast moving world, why is a natural history museum so important?

JM: Well, I think, loads of reasons.

If we’re all talking about doing what we can to save the planet, if you want to show what the planet has to offer, to give that sense of wonder in the natural world, and to make people think, a natural history museum is one of the best places to go.

For example, going back to the deep sea, a lot of people think, well, it’s down there, it’s deep, it’s dark, how does what goes on down there affect me in any way at all? [But] there are plastic bags blowing around at the bottom of the deepest bits of the oceans, so what we’re doing is affecting life throughout the whole plant. We did a scientific project on some of the fish we brought back from the Atlantic trip I went on. There was a woman called Alex McGoran who looks at microplastics, and she found microplastic fibres in two thirds of the deep sea fish that we brought back. We didn’t do them all, we just did a little sample of them, but of that sample, she found plastic fibres in two-thirds… and these are things living right out in the middle of the Atlantic.

So, I think [we need] to be able to tell that story as well, and to say, look, every time you use your washing machine, you’re washing out loads of little bits of plastic, and that’s getting its way through the whole ecosystem. But not just to depress people as well, but just to again, give people that sense of wonder and to show them how rich and exciting the natural world is. I think museums are a fantastic place to do that.

MNC: Did you by any chance catch that Netflix documentary, “Seaspiracy”?

JM: Ahh. I’ve heard such conflicting things about it. I know it’s made a lot of people really angry. I’ve heard that, although its heart is in the right place, some of the sciences isn’t to be trusted in it. That’s what some people who know more about it than I do have told me. But, I couldn’t bring myself to watch it … the impression I get is that, in order to get the message across as strongly as possible, they’ve kind of over-egged the pudding a little bit in places, I think. But yeah, when it comes to Netflix, I think my favourite documentary is the one about the octopus. Have you seen “My Octopus Teacher”? That, I thought was fantastic. That was great. I love it. If I wasn’t working with fish, I’d be working with octopuses I think. They’re absolutely amazing.

MNC: Speaking of movies and things like that, how often do movies depicting museums and the job of a curator get it right? And do they help or hurt the profession?

JM: Hmmm… so, who have we got? We’ve got Ross from Friends haven’t we.

I think usually, the fictional version of a curator is a slightly weird, socially inept, freak person, and although there are elements of that, I like to think we’re a little bit more approachable. I mean, I think being a little bit geeky goes hand in hand with the job. I think, because obviously I love fish, and I also like putting things in order and making [sure] everything’s all correctly put away in the right place. So, I think being a little bit that way inclined definitely goes with the job, but I don’t think we’re as weird as people make out sometimes.

Keyholder: I was going to ask whether you engaged with children’s groups going round, because I remember going there with a brownie group when I was, I should think, about 7 or 8, and I remember how much I enjoyed that and I was wondering to what extent you get a chance to chat to children or see what children’s reactions are like, when they are visiting the museum?

JM: Oh, absolutely. It’s one of my favourite things. Every time you see a little arm go up, you just do not know what you’re going to get thrown at you, and they ask the best questions. They ask much more intelligent questions than the adults.

We used to do an event, which I’m sure we will do again once everything starts to open up, called Dino Snores where, I can’t remember how many kids it involved, but they all come and spend the night at the museum and they need to be entertained, so we do three shows for them. We do one specifically about the deep sea and we show them a screen with little lights in it and we ask them to guess what’s making the lights. So yeah, I love working with kids. It’s great, yes.

[ And, if that sounds fun, they host the Dino Snores events for grown-ups too… ]

MNC: Speaking of which, what advice would you give to someone wanting to become a curator?

JM: Well, sadly it goes back to what we were saying before. At the moment, the best thing to do is find your local museum, get in touch and see if you can go and give a hand at the weekend or whenever you’ve got some free time. Just to learn about how looking after a collection works, get the basics, and then that will hopefully lead onto other things. When people like me retire then hopefully this younger generation will be coming in, and have the same sort of love for it that we do.

Keyholder: Have you ever, or how often do you collaborate with, other Natural History Museums?

JM: All the time. Quite often we have visiting researchers who are looking at a certain group of fish. We don’t have all the specimens here, but what we will do is, we will borrow ones from other museums and get them all in one place so the researcher can come and examine them all. So we do share things. It’s almost like inter library loans where we send things around to other museums. We like to give each other things as well. We do exchanges, so if we have a lot of one kind of thing, we will do a swap with another museum and if somebody is somewhere describing a new species, what they ideally want to do is have a set of specimens that represent that species and they then become very important. They’re what we call “type specimens” and they’re the specimens that if you want to do anything on that species, they’re the ones you have to go and check against, and so what they like to do now, is if you have a lot of these specimens, is to distribute them in all the museums. So we give each other these important type specimens as well and we’re just in contact all the time too, and they come and visit us, and we go and visit them, and you know, if I find something… It’s like I was talking about earlier. I have so many contacts now in museums all over the place and I know who’s working on which group of fish and if I find a strange one I can just contact, you know, Kevin in Texas, and say, “Hi Kevin, do you know what this is?” So, it’s like a real network.

MNC: That’s fun. So there’s no rivalry between you and the Natural History Museum in New York, for example?

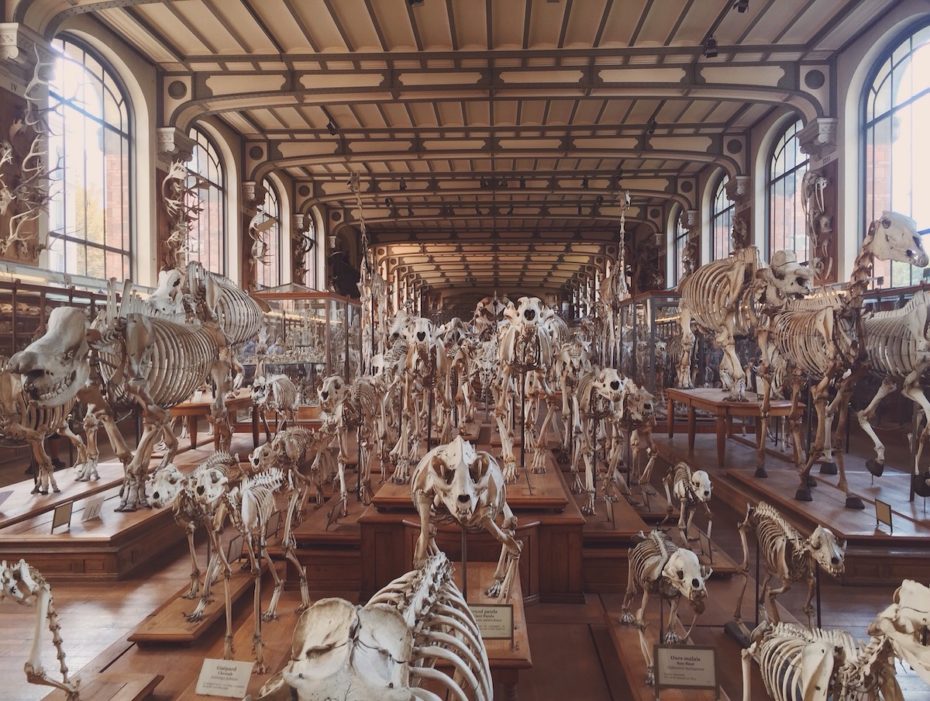

JM: No, not really. I think the big three are Paris, Smithsonian and us. There’s a little bit of jostling at the top about who’s got the most stuff, but it’s all very amicable.

MNC: Ok, I’ll take your word for it.

Keyholder: What is your favourite museum apart from the Natural History Museum in London? Is there one that you dream of going to?

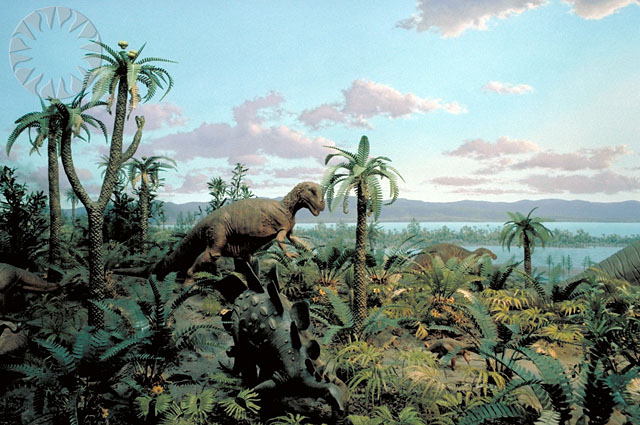

James: Ooh, that’s difficult. New York and Paris are both just incredible. Paris is another one that has that space, that when you walk into that main hall, especially if you’re in one of the upper levels and you look down at it all, it’s just amazing. And New York, I think, I really love the old dioramas that they have there, you know, where they’ve got the specimens and they’ve made like a complete little world for them to be in with all the plants and everything. I think those are really fantastic. I think New York might be my other favourite, just.

MNC: You were talking about [how] you’re lucky to have this network of friends that work in all these museums. When you go to, for example, the Paris one, where I know that they have this huge underground vault, are you able to visit behind the scenes?

JM: I usually know one or two of the curators or the researchers there, so if I’m feeling cheeky I can get in touch and say, “would you mind showing us around?” There’s also a great organisation called SPNHC, which is the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections. They have conferences every year normally, and they’re based in a museum. They have these fantastic events where all the curators turn up to one place. Then they get to meet people, go on collection tours and get a chance to see what other people do. That’s a lot of fun.

Keyholder: Do you have an aquarium at home?

JM: I have four aquariums at home, yes. One wall of my living room is just a row of aquariums and yeah, I’ve got puffer fish and loaches and then I’ve got a sort of Amazonian tank. I’ve got another tank with some gouramis in it. So, yeah, I take my work home with me a bit, yeah.

Keyholders : Do you eat fish for dinner?

JM: I eat some fish. If it’s been sustainably sourced I will eat it, but I try not to eat it too often, and there are some things that I absolutely would not eat. I wouldn’t eat shark fin soup for example. And since watching my octopus teacher, I haven’t been able to eat octopus.

MNC: Have you ever broken something?

JM: It does happen… I haven’t broken anything for a while. Occasionally, I have broken a jar, and that’s uh.. especially if it’s a really old one, that does make me feel a bit sick. But, that doesn’t happen very often.

MNC: Ok, well, this has been really, really lovely. I guess we will leave you to save the museum beetles. Good luck with keeping them alive.

Follow James Maclaine on Twitter and keep up with the Natural History Museum’s news on Instagram.