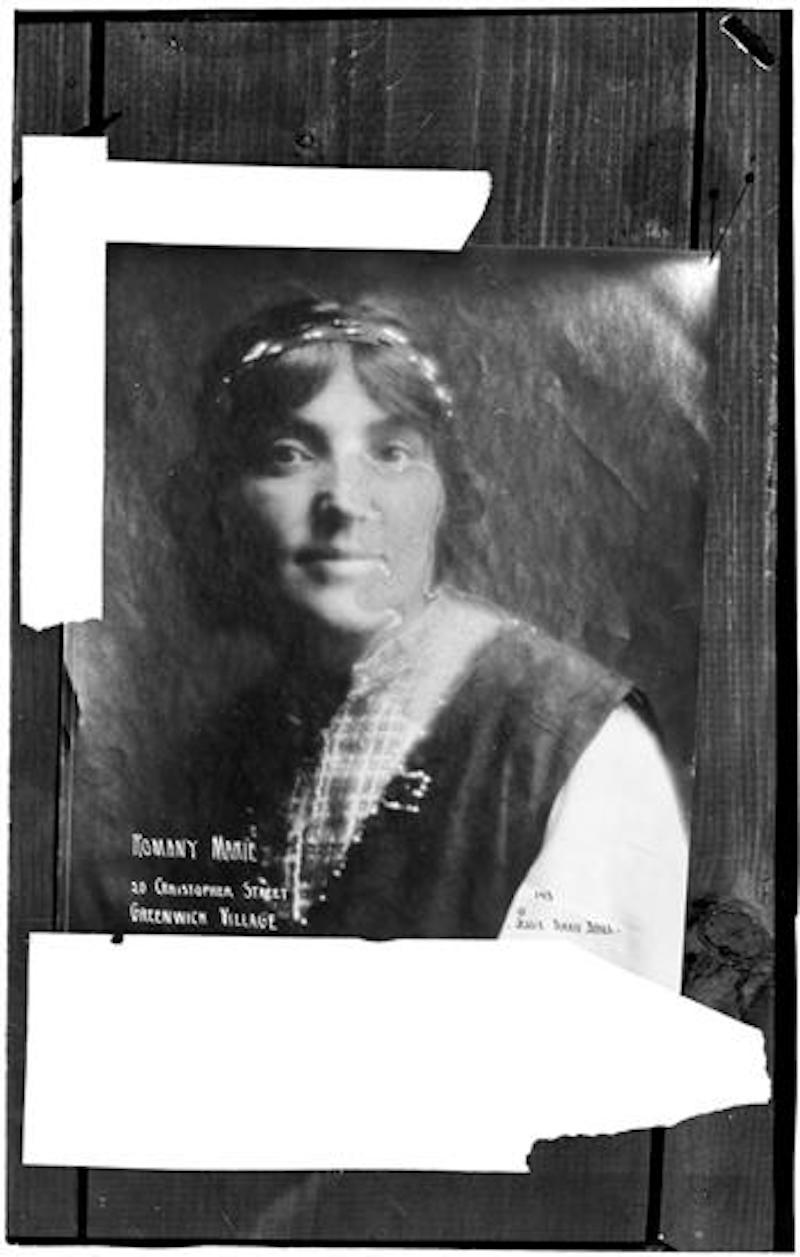

Marie Marchand, better known as Romany Marie was one of those eccentric characters that stood out in a town full of them. During the first part of the 20th century, her informal Greenwich Village cafés drew a society of artists, anarchists, activists, playwrights, musicians and bohemian intelligentsia. If you were looking for la vie bohème in New York City, you found it chez Romany Marie. Picture Stevie Nicks meets Gertrude Stein and you’ll start to get an idea of the kind of woman who single-handedly established Parisian café society in the Big Apple. So how did the village forget its most prominent café queen?

Despite appearances, and having been born in Romania, Marie wasn’t actually of Romani origin – one of Romania’s largest minorities; a Indo-Aryan people, traditionally nomadic; and more carelessly referred to as “gypsies” (a pejorative term historically imposed by Europeans). It is, after all, part of the Roma tradition to gather; to offer hospitality and exist together in community rather than in a fragmented society – something Marie likely yearned for as an immigrant in America, which had adopted her own nomadic tendencies. She united the melting pot that was Greenwich Village at the turn of the 20th century and played a key role in establishing the bohemianism that would define the Manhattan neighbourhood for generations to come. Her story landed in our inbox one day when her great-niece, Lois Gilbert asked us if we’d heard of her New York tale. “She was a wild child left on her own, learned from nature and yearned to be free and to be with those that thought like she did,” Lois told us.

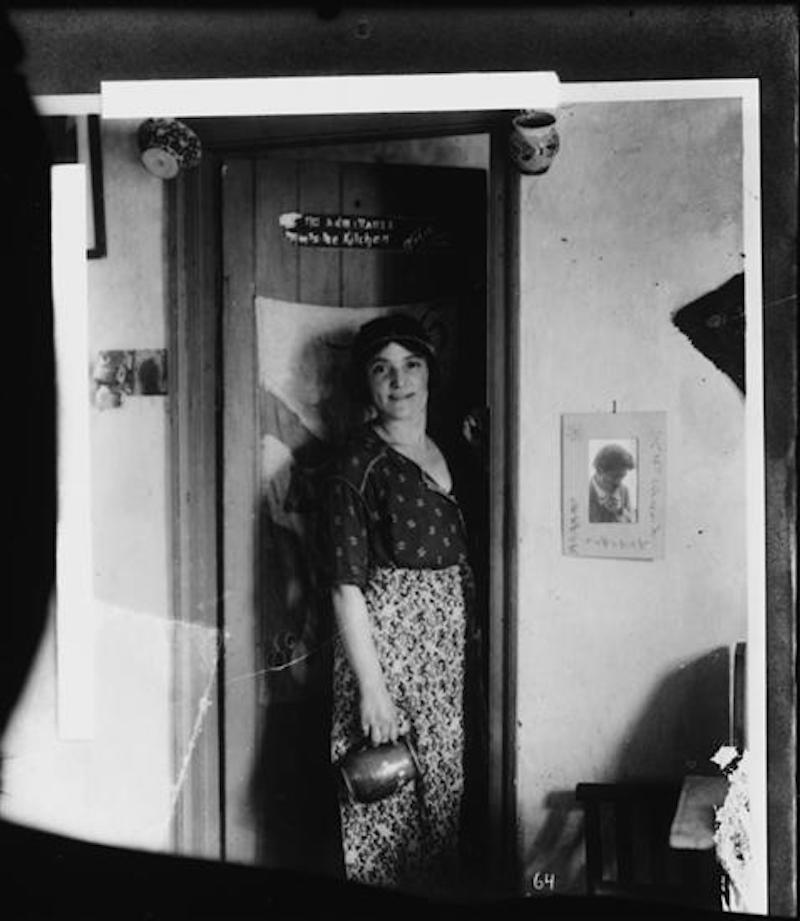

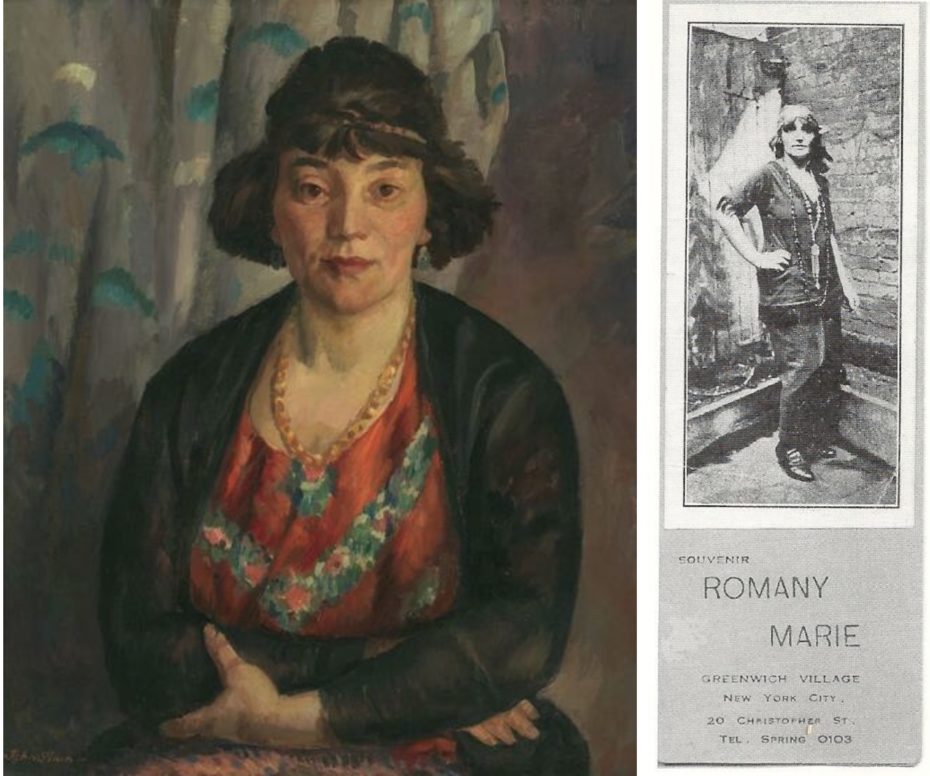

Marie moved to New York as a teenager with $150 in pocket and worked in sweatshops as a seamstress with her mother, three sisters, and younger brother. Once she learned English, she joined a theatre and attended activist thought groups and started inviting like-minded souls to her home, warming their spirits in a lingering tempo. Her guests encouraged her to open her own tavern; a European-style bistro-cum-Parisian salon. Marie opened her first café at the corner of Sheridan Square in 1914 and became known for her Turkish coffee, which she would serve with a complimentary reading of the patron’s fortune. She didn’t consider herself a bonafide fortune teller, but she revelled in company, putting on a show every night in her colourful and free spirited outfits, her arms decorated in bracelets and jewellery; a true bohemian at heart.

Throughout the course of 30 years, her establishment would change location at least a dozen times. She would leave a note overnight: “the Caravan has moved,” and change location. Marie fed anyone as long as they offered her an exchange of art, curious conversation, or good company. This also meant that her income was continuously fluctuating, but she was becoming a local mother of the arts, always offering the struggling artists her renowned Romanian chorba stew.

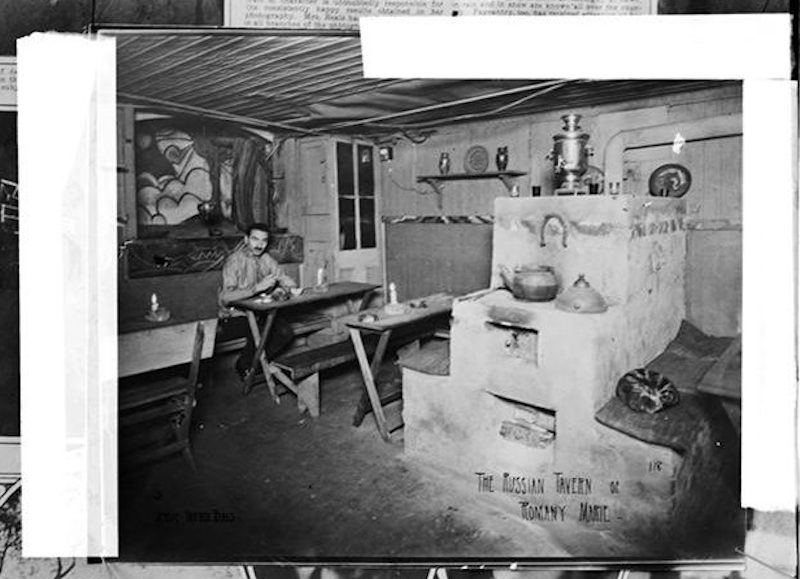

During her 35-year reign in the village, she sheltered all sorts of anarchists: Wobblies, Socialists, Communists, and even vegetarians! New York’s “lost generation” they were called. She had established a Rive Gauche of her own, and it was one that even Paris knew about. Before there were speakeasies, her tribe of liberals would always find their way to her locations, which were often hidden up several flights of stairs or at the ends of alleyways. Describing one of her locations on Minetta Lane, Rian James wrote “only a surveyor could find it” in his 1930 book, Dining in New York. Other locations included 55 Grove Street (next to the now famous piano bar Marie’s Crisis), St Mark’s Place, Washington Square South and the basement of the Hotel Brevoort.

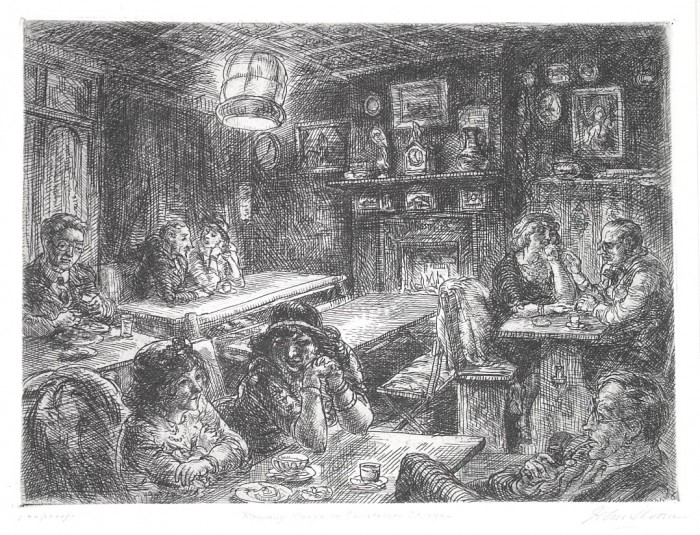

Marie never cared about opulence; her cafés were ones that fed philosophy. She managed a so-called patron’s table where the most interesting people would gather in conversation around a fireplace. You can bet that every artist, writer, and thinker worth their salt in New York City at that time befriended the hostess and had at least one free meal there. The American inventor and futurist, Richard Buckminster Fuller, who compared Marie’s establishments to the cafés of Paris, was a regular and gave “thinking out loud” lectures several times per week. The famous Romanian Modernist and sculptor, Constantin Brâncuși, whose work made it big in Paris in the early 1900s once brought Henri Matisse. Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote “my candle burns at both ends” in Marie’s salon. Painter John French Sloan, best known for his ability to capture the essence of neighborhood life in New York City, was also a loyal customer and painted Romany Marie’s portrait in 1920, which now hangs in the Whitney Museum of American Art. Arctic expeditioners and prestigious paleontologists from the nearby Explorers Club were said to have been equally at home with the bohemians at Romany Marie’s as they were “in the elite chambers of the American Museum of Natural History [or] when camped in a field hunting for fossils”.

Other notable guests at Marie’s included Diego Rivera, Orson Wells, and novelist Fannie Hurst. Everyone who was anyone on the art scene passed through Marie. “She was a Vesuvius of creativity in heart and mind,” recalled Buckminster Fuller. The pamphlet advertising Romanie’s read as follows:

In these sad dry days, Manhattan yams in gigantic boredom. Broadway and its garish lights? No! Then where? Then what to do? But just suppose there was a place with a peasant atmosphere? A place that gave an honest glimpse of “Romantic Romania?” A place where coals grow on an open grate? Where, instead of jazz, come soft languid gypsy aurs of the old Carpathians?

A place where one sips Turkish coffee and fragrant drink? A place serving a table-d’hote dinner or dishes so delicious that they tempt the jaded palate? What then? Would that amuse you? For there is such a place!

Many of her male patrons even fell in love with her, and she often indulged their attention, but remained faithfully in love with her husband Marchand. She ultimately had to discontinue her service at her tavern in the late 1950s when he fell ill. Every person to step through the threshold of Marie’s tavern left with a little bit of wisdom from the bohemian queen herself. Every artist needs a guide and Marie was like the fairy godmother of all struggling and poor artists of NYC. Hers was a place for outsiders who were actually insiders to one of New York’s best kept secrets.

As the city comes alive again and the hospitality industry strives to reinvent itself, we hope to find Marie’s spirit once more, lurking in the nooks and crannies of a renewed roaring twenties restaurant scene.