The business of death is one as old as time. Today the market size of global death care services is valued at over $100 billion annually and it’s expected to double in the next decade too (an increase attributed to more demand for lavish funerals). But there’s a lesser-known “service” of the industry which those numbers probably don’t account for. “When a loved one dies, you grieve so much that when it finally comes time for the funeral, you don’t have any tears left,” says Liu Jun-Lin, a young professional mourner from Taiwan. Her occupation – professional mourner – dates back as early as Ancient Egypt and the practice is mentioned in both the Old and New Testaments. Whilst a silent, weary or under-attended funeral might be what many of us have come to expect, in China and some parts of Asia, Africa and Europe today, such a low key send-off can be considered seriously bad luck. So let’s meet the enterprising few, who will cry on cue for cash…

One of China’s most sought-after mourners is famous for her displays of crying, crawling and shouting at funerals, a dramatic funeral performance known as kusang. In eastern cultures, the hired mourner is explicitly performing a cathartic role for the family and friends. Hu Xinglian, professionally known as Dragonfly, Mao told NPR, “A big part is saying the last goodbye to the dead person. We need to show our feelings for others to see, and to display the filial piety of the offspring,” she says. “Some people can’t cry. So I use my heart to sing this song to represent the loss.”

Here is Hu Xinglian at work:

It’s essentially the same function performed by the “wailing women” of the bible, referenced by more than one ancient prophet. Jeremiah, who is revered in the Christian, Islamic and Jewish tradition, tells his listeners: “Consider now! Call for the wailing women to come; send for the most skillful of them. Let them come quickly and wail over us till our eyes overflow with tears and water streams from our eyelids.”

In Ancient Greece, if the deceased was from an upper-class family, a large number of professional mourning women were hired to spice things up at the funeral. These professional mourners would sometimes literally rip out their hair in a display of fabricated grief, accompanied by musicians leading the procession. They were often also followed by an Archimime, an ancient roman jester who imitated the manners, gestures, speech and even the dress of the deceased. Julius Caesar hired a funerary mime – it was a sign of success to have a hired actor imitate you after your death; proof that people cared enough to know what kind of man you were. During funerals, an archimime would walk behind the casket, dressed in the dead person’s clothes and wearing a mask of their likeness, all the while waving at the people observing the procession and imitating the deceased as if they were still alive.

Not only would there be a hired mime imitating the deceased, but also to imitate the family in mourning. The funeral director would employ people known as “imagines” to disguise themselves as the family to follow behind the funerary mime, greeting the crowd so the departed’s real loved ones didn’t have to. It was also a way of showing off just how important you really were. The actors would dress in clothes that showed off the highest rank the deceased’s family had reached in life.

In wealthy British society, professional mourners came to be known as a “mute”. A funeral mute would stand watch outside the house of the deceased and then accompany the funeral procession from there to the cemetery. The mute was considered to be the symbolic protector of the newly departed person and contributed to the general atmosphere of mourning with their black crepe covered hats and staffs. In the case of a child’s funeral the hat and staff was covered in white. The most famous reference to a funeral mute is found in Oliver Twist when a funeral parlour owner takes Oliver from the work house and explains to his wife: “There’s an expression of melancholy in his face, my dear, which is very interesting. He would make a delightful mute, my love”.

Demand for the work of funeral mutes declined over time and disappeared from mainstream English society by the early twentieth century, likely in part because of the reputation of mutes to accept their payment in alcohol. “I have seen these men reel about the road, and after the burial”, notes one writer for a late 19th century society periodical, “we have been obliged to put these mutes into the interior of the hearse and drive them home, as they were incapable of walking,”

In remote villages in Greece and Italy, elderly women are still hired as “moirologists” (moíra meaning fate and speech) not just to grieve people they don’t know, but also to sing in right harmony as they lead a family through the final moments with their loved one. “The songs retell the story of a grieving person’s life in quick-witted improvisations,” says photographer Ioanna Sakellaraki, who returned to Greece to document this ancient practice. “Historically, families were asking for women to do this process because it was just so important — it was an important sort of collective goodbye to the person.” The tradition will likely disappear within a few years as the last moirologists, some nearly 100 years-old now, take their own leave, having notated very few of their traditional mourning songs.

In England, professional mourners employed by a company called Rent-a-Mourner paid actors somewhere between $30 – $120 per funeral to play a distant cousin or uncle, helping families increase the number of guests. And fun fact: actress Diane Kruger earned some pocket money in her early teens as a professional mourner in Germany, where you can also hire a professional funeral speaker, known as a Trauerrednerare, to read a eulogy despite never having met the deceased.

The 1995 South African novel, Ways of Dying follows the wanderings and creative endeavors of Toloki, a self-employed professional mourner, as he traverses shantytowns in post-apartheid South Africa where you can still pay someone to cry at a funeral. It’ll cost you a little extra for them to threaten to jump into the grave.

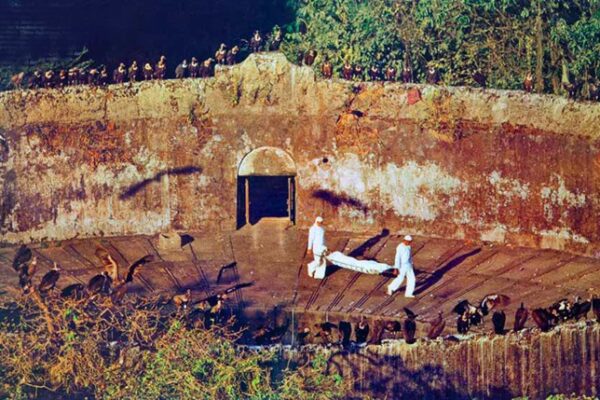

Artist Taryn Simon found the different forms of professional grieving so interesting that he committed seven years to mounting an extremely unique exhibition in the UK in 2018, a performance gathering of professional mourners from many countries in one space.

“Each night audiences visiting ‘An Occupation of Loss‘ descended from the busy Essex Road into a half-built, subterranean, concrete opera-house where professional mourners simultaneously broadcast their lamentations, enacting rituals of grief from around the world.”

In the words of one professional mourner with many years of experience, Owen Vaughan, a “career griever” based in London, England, “some of you are still firmly of the opinion that this is a sleazy business. After all, what we’re doing involves lying right to people’s faces, at a time when they’re at their most vulnerable. But remember the part earlier about how when you hire us, you get the full mourner package – including mingling with the crowd and helping people talk through their grief. That is, after all, what funerals and wakes are for. People have been gathering to do this for as long as there have been people. Share stories, cry, get closure. I help people do that. It’s why I took the job.”