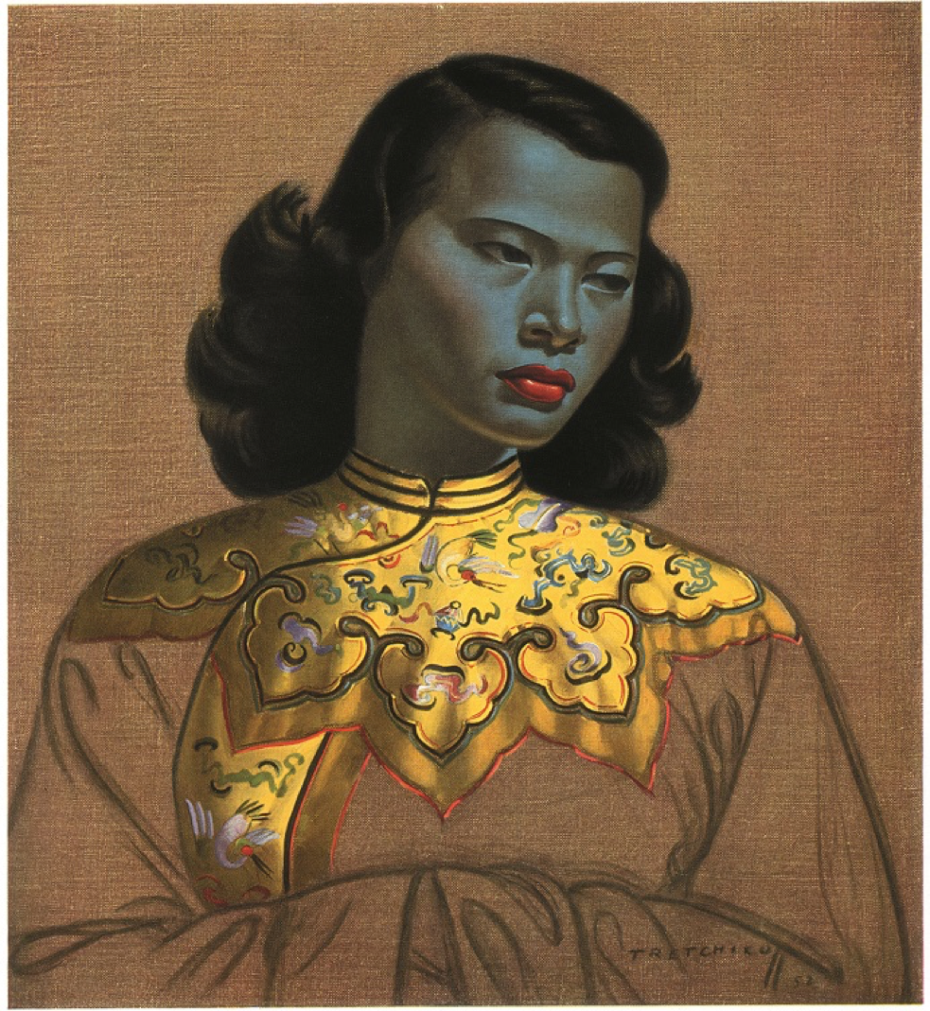

Chinese Girl, the most famous of all Vladimir Tretchikoff’s paintings

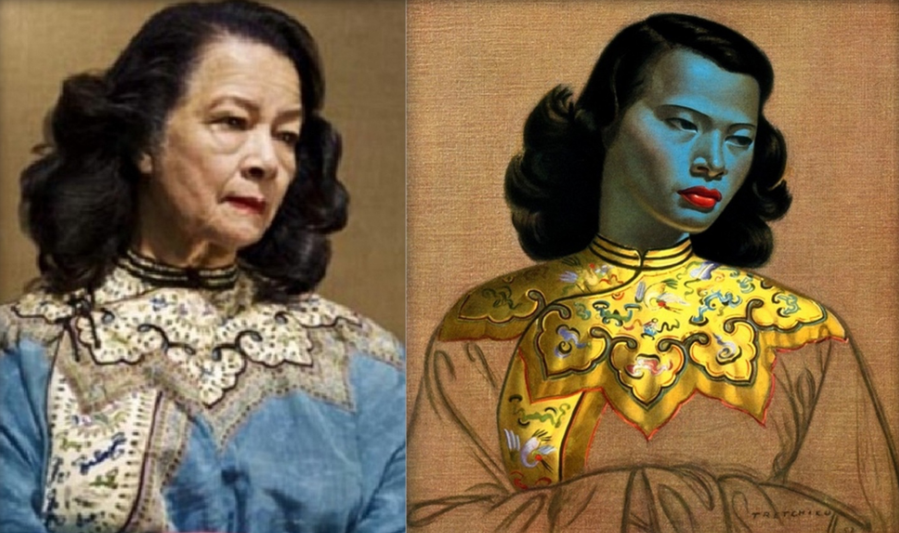

It’s a breezy day in 1950s Cape Town. Monika Pon-su-san is busy serving a customer in her uncle’s laundromat when a curly-haired, angel-faced stranger walks through the door. Vladimir Tretchikoff’s gaze is fixated on her – an exquisite young beauty with lustrous dark hair, full lips and a shy smile. He needs to paint her. She agrees to be picked up after work, he gives her his wife’s silk chiffon gown to put on, and the rest is (art) history.

A painting with unfathomable universal appeal, one that has sold more copies than any other – including the Mona Lisa – begins to take shape on Tretchikoff’s canvas. The Chinese Girl, commonly known as the ‘Green Lady’ comes to life in all her iridescent glowing glory, a blue-green patina-like sheen across her melancholic face, her hypnotic gaze diverted. She’s serene and mysterious and at the same time familiar and endearing. She’s a picture of contemplative, otherworldly spiritual beauty. It’s with the utmost difficulty that one manages to drag one’s own gaze away from the dazzling beauty on the canvas.

One of the most famous faces in the art world, Monika Pon-su-san went on to live a conventional life in Johannesburg and brought up her 5 children, working as a shipping clerk and dressmaker after her marriage fell apart. She later admitted she was mortified when she first saw the complete painting of Chinese Girl – she thought this apparition with its green face was something from a horror film. But when Monika finally decided buy a print for herself they were sold out, so Tretchikoff gave her one of his own. It hung in Monika’s lounge. Close to the end of her life, when one of her daughters told her the painting was sold for £1 million, she jumped up and down in bewilderment, never fully comprehending her role in this extraordinary success story. Monika died at the age of 86, on June 14th 2017 in Johannesburg.

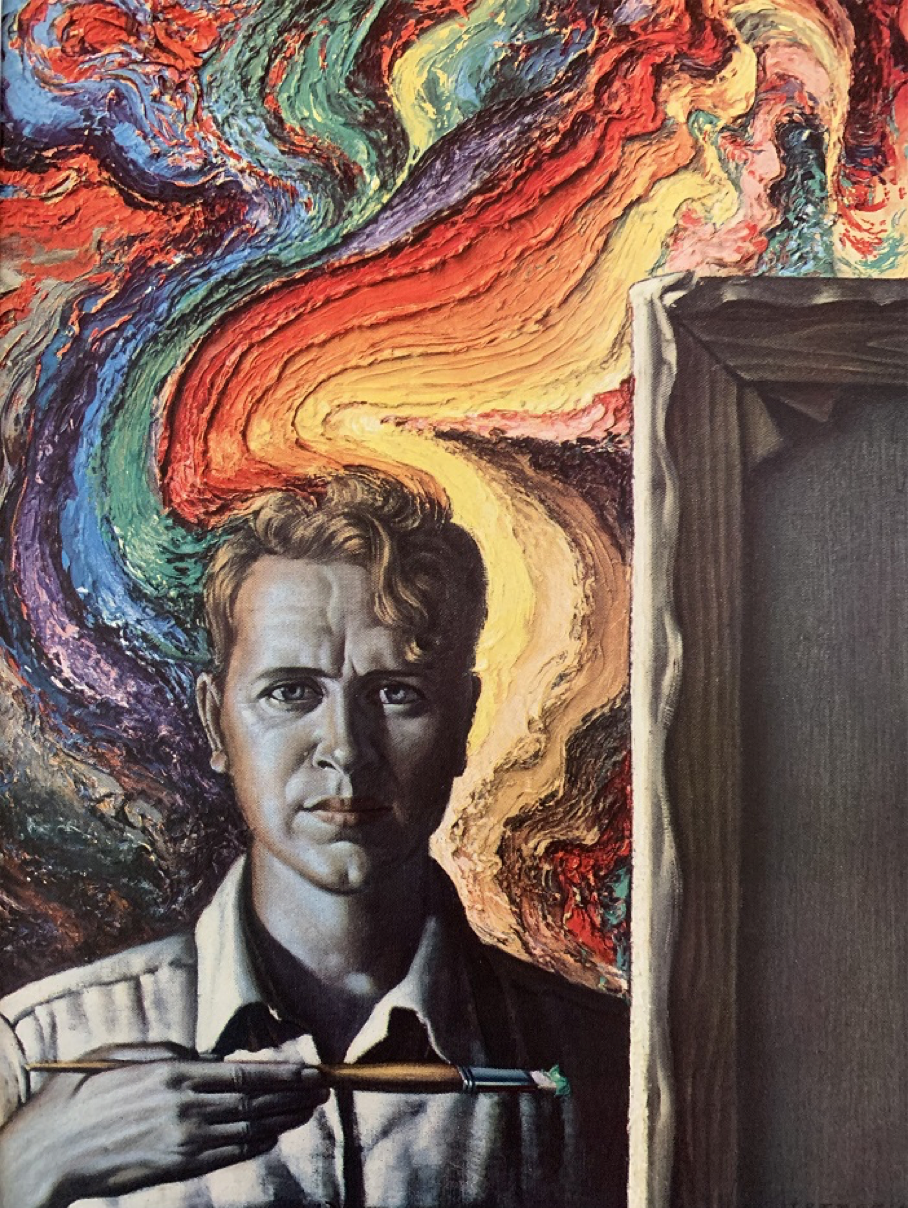

Tretchikoff’s is not by any stretch of the imagination, what you’d call an ordinary life. In fact his story reads like the quintessential Ian Fleming spy thriller. It has its fair share of bombardment, narrow escapes, boat chases, solitary confinement, heartbreak and happy endings. It crisscrosses continents, it’s fraught with peril and challenge, its filled to the brim with passion and intrigue, fame and glory, disappointment, sadness and elation. And inextricably woven into the labyrinth of Tretchikoff’s life are the extraordinary women who crossed his path, each with their own journey and story to tell – his beautiful wife Natalie, his many inspiring muses, his daughter Mimi – the apple of his eye – and his four granddaughters.

Born in Petropavlovsk, Russia (now Kazakhstan) in 1913, the ‘King of Kitsch’ was one of 8 children in a happy family, but no thanks to the Russian Revolution, his idyllic family life was shattered and the family dispersed across the globe, never to be reunited again. At age 5, young Vladimir, already showing artistic promise, settled with some of his family in Northern China. In his mid-teens he received a commission that took him to Shanghai where he met his future wife Natalie, a comely 17-year Russian brunette.

Soon thereafter, the couple left for Singapore where he took a job at an advertising agency and on the eve of WWII, Tretchikoff joined the British Ministry of Information as a propagandist artist. War broke out, Japan bombed Singapore and evacuations began. He said his tearful goodbyes to Natalie and Mimi, not knowing if he’d ever see them again (only after the war, he’d find out they’d been shipped to faraway South Africa). In 1942, he boarded a small ill-fated boat heading into the open sea from Singapore. The armed vessel was heavily bombed and many drowned. Tretchikoff and the other survivors swung between life and death on sea for 19 days until they found land on the occupied coast of Java, where he was captured and placed in solitary confinement for three months. He was interrogated for three days, suspected of being a spy for the British and initially kept in isolation. But somehow art saved him. He managed to convince his captors that he was an artist and not a threat. Throughout the war years he painted prolifically and produced some of his best work.

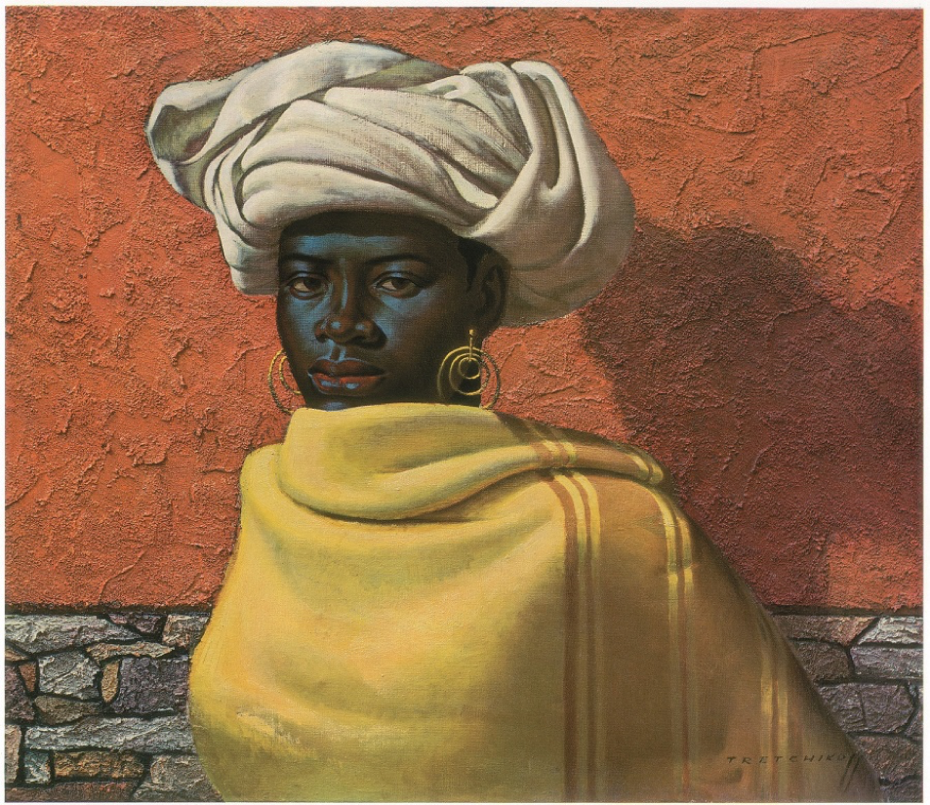

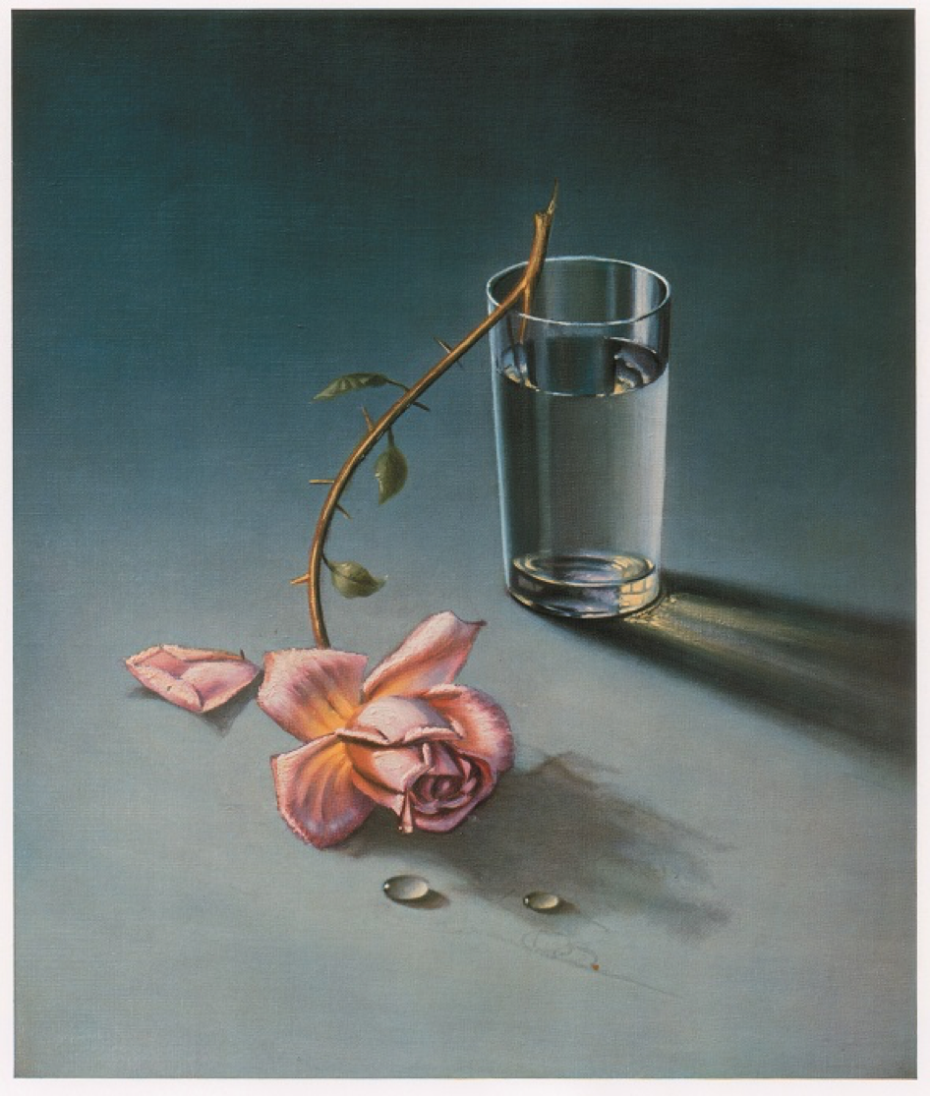

Every Tretchikoff picture tells a story, and it is this intriguing quality that may well be part and parcel of the secret of Tretchikoff’s universal appeal. Who is she? Where does she come from? One can’t help but wonder if it is this psychoanalytical and escapist aspect of the paintings that so draws us to the subject matter.

The fact that many of Tretchikoff’s muses possess an otherworldly beauty – half Eastern, half Western, half African, half European, almost independent of time, place and culture, mysterious and, yet accessible and familiar, makes for a heady and intoxicating cocktail in terms of subject matter. Not only did Tretchikoff have an uncanny eye for spotting the intangible quality of unusual allure, he also managed to capture and immortalize this magic so beautifully with each self-taught brushstroke.

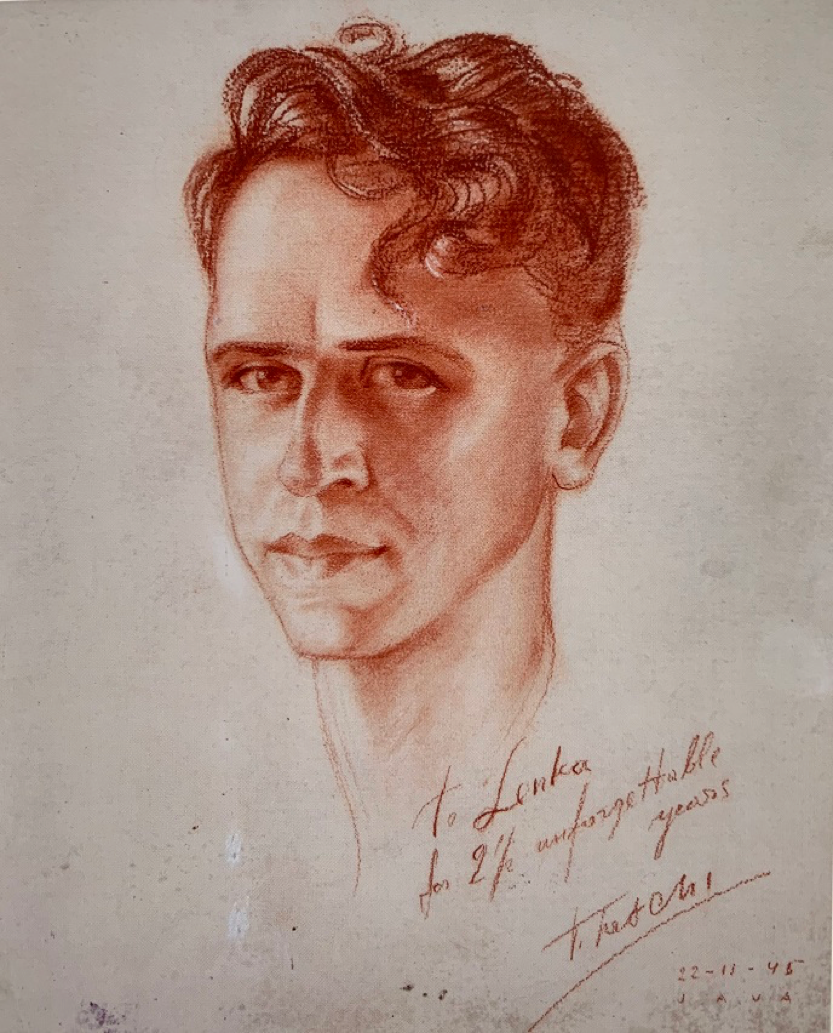

It was during these years in Java that he met one of his muses and the other profound love of his life, Leonora Moltema, or ‘Lenka’, a striking Eurasian woman who worked as an accountant and who he met when she came to have her portrait painted.

In an interview before his death he said, closing his eyes, a gentle smile on his face, ‘I can still smell her perfume. She wore Shalimar. She always dressed like a Paris model and had coal-black eyes and shoulder length hair. She was stunning.’ (Yvonne du Toit, Tretchikoff, The People’s Painter: p.92). Tretchikoff soon asked her to model for him in the nude and she agreed after some initial hesitation. The famous painting Red Jacket featured Lenka’s own scarlet jacket.

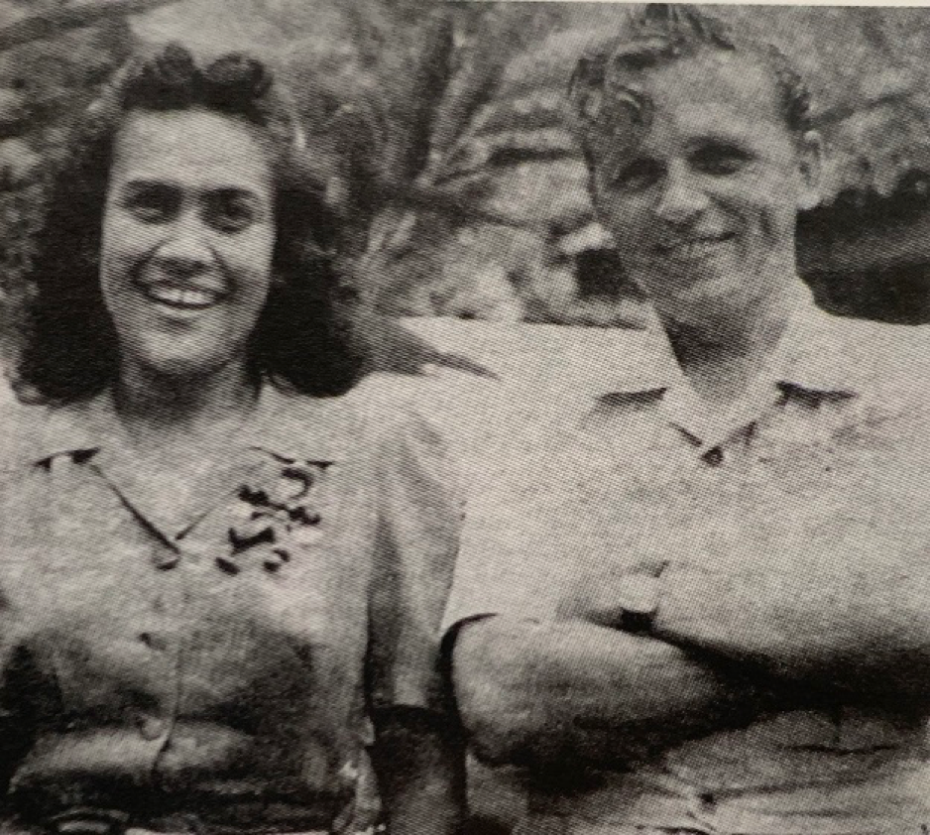

After the war, when he was reunited with his wife, he confessed his relationship with Lenka to Natalie and offered her a choice of any of his work. She chose Red Jacket, the nude study of Lenka and hung it above her dining room table. When the war ended and Tretchikoff learned that his wife and daughter were alive and well and evacuated to South Africa, Lenka decided that he should be reunited with his family. On August 13th, 1946 he arrived on Platform 13 (no. 13 was Tretchikoff’s lucky number) to be met by an elated Natalie and his daughter Mimi. He lived out the rest of his life in Cape Town.

As for Lenka, she eventually settled in Holland, got married and when her husband died, ran their family business very successfully. In 1998 she made a trip to South Africa to see Tretchikoff after 35 years, stepping off the plane in a regal red suit, right into the arms of the waiting Tretchikoff. Lenka died on August 1st, 2013 at the ripe age of 99.

Today, Tretchikoff’s granddaughter Natasha Swift remembers a warm and gregarious, if sometimes a tad domineering man, who was more of a father figure to her than grandfather. He had a love of surprises and bestowing gifts on his grandchildren and went out of his way to celebrate family occasions in memorable style. She fondly recalls how he used to tie cards to pieces of string, making his grandchildren, panting with excitement, venture around the corner to look for their gifts. Tretchikoff died a wealthy and happy man in 2006, a year before his beloved wife Natalie passed away.

Throughout his prolific artistic life Tretchikoff’s work and character have been mocked and scrutinised by avant-garde critics and art intellectuals across the globe as ‘kitsch’ or ‘garish’, but he steadfastly kept creating his brilliantly coloured, stylized pictures to cheer up a dull world. They appealed in equal measure to housewives in London, bank clerks in Hong Kong, company executives in New York, sheep farmers in Australia and township folk in South Africa.

Despite being marginalised and mocked by the art establishment, Tretchikoff’s art had, and still has, immeasurable crowd appeal. He was the first artist to mass-produce and deliberately sell reproductions of his art to enable the masses to enjoy it too. His granddaughter Natasha Swift reckons part of the genius of Vladimir Tretchikoff was that he retained the copyright on his artworks after he had sold the originals. ‘Why should my art only be available to the wealthy? I want everyone to enjoy my art.’ He went out of his way to exhibit in accessible locations – shopping centers and banks, amongst others, treating his own work as a product and commodity – albeit a product that he loved dearly and wholeheartedly believed in.

Tretchikoff’s work continues to challenge the puritanical and elitist snobbery of contemporary art. No wonder few other painters (except perhaps Picasso) made more money than Tretchikoff. While Renoir admittedly paid his rent with his canvases and Van Gogh despaired to the point of cutting off his ear, Tretchikoff thrived and was famous in his own lifetime.

The Chinese Girl painting sold millions of printed copies, appeared in films like Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Frenzy’ and made cameo appearances in music videos like David Bowie’s “The Stars Are Out Tonight’ and The White Stripes’ ‘Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground’. In fact, art pundit Andy Warhol allegedly said, ‘It has to be good. If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.’ According to Boris Gorelik who wrote extensively on Tretchikoff, ‘his prints became an in-thing, a respectable and yet affordable piece of sentimentalism with which to adorn a lower or middle-class home’ and took pride of place above innumerable mantelpieces across the world. The Chinese Girl painting itself made an intercontinental journey and came home after decades: it was sold to a woman buyer in Chicago in 1953, then sold at Bonhams in 2013 for close to a million pounds to the jeweller Laurence Graff. Today the painting is sitting at the entrance to the prestigious Delaire Graff wine estate outside Stellenbosch, South Africa, so close to the public in physical proximity one can literally touch it.

The magic of a Tretchikoff painting is that it needs no signature, it’s instantly recognizable. It’s likely to evoke a lucid flashbulb memory moment as to exactly where and when you’ve first seen it, who you were with and how you were feeling at that particular moment. Or at the very least, like an iconic song it elicits a warm fuzzy feeling deep down in your core. Is that not the ultimate litmus test?

As for his beloved bevy of muses, we suspect they’re busy working their magic in another time and place, no doubt winking mischievously as they exchange gossip about the cherub-faced man who adored them all.

With huge thanks to Ari Lazarus and Natasha Swift for their help, as well as to The Tretchikoff Foundation and Tretchikoff Project.