When an artist named George Maciunas looked up the word “flux” in the dictionary in 1960, he found seventeen definitions. “Flux” can be used as a verb, an adjective, or a noun. The multiplicity of the word made it the perfect term for the art movement he was in the process of creating; a loose collection of artists, writers, scholars, and performers whose interdisciplinary work was on the cutting edge of the sixties avant garde. Fluxus encapsulated the question eternally proposed by the avant-garde: “what is art?” Can silence be music? Can a wedding or a funeral be a piece of performance art? Can art really be made by anyone? The most recent evocation of this question has come with the rise of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) within the crypto industry. Digital assets are fast gaining momentum in the art world and became one of the biggest buzzwords of 2021. And while the concept of NFTs may still be a black box to many, it’s not entirely novel. Much like the radical art of Fluxus, crypto art is difficult to “collect” or own in the traditional sense, and both concepts essentially remove art from mainstream museums and white gallery walls. Long before the internet and crypto mania, Fluxus worked to overturn cultural conventions and hegemonies and with George Maciunas at the helm, the movement revolutionarily declared that art was for everyone and art could be anything.

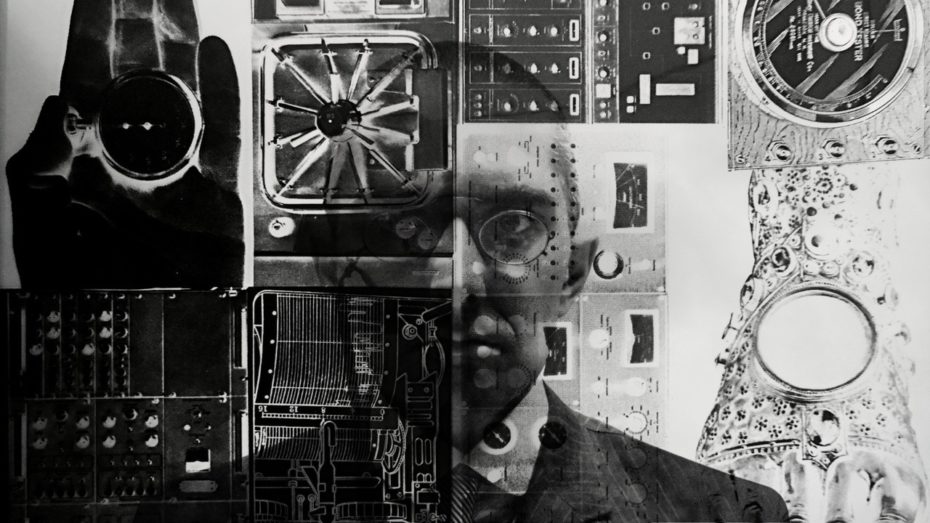

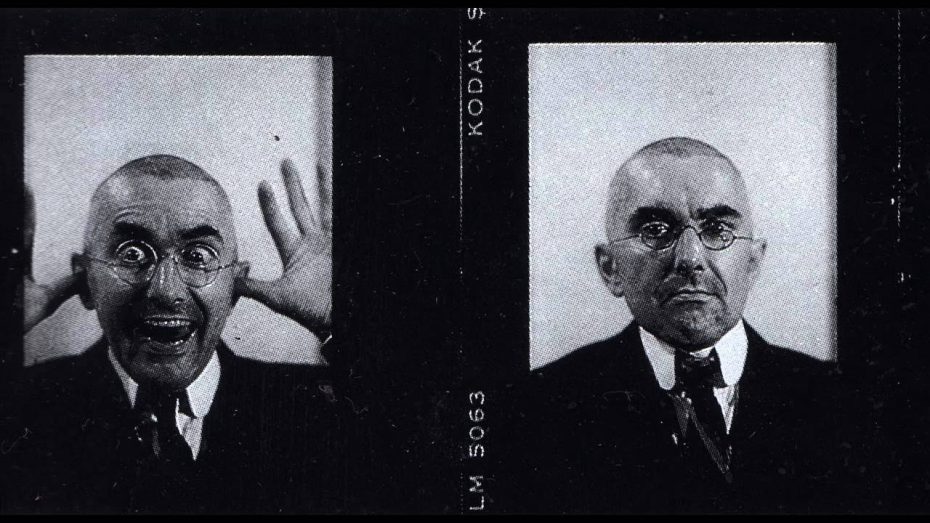

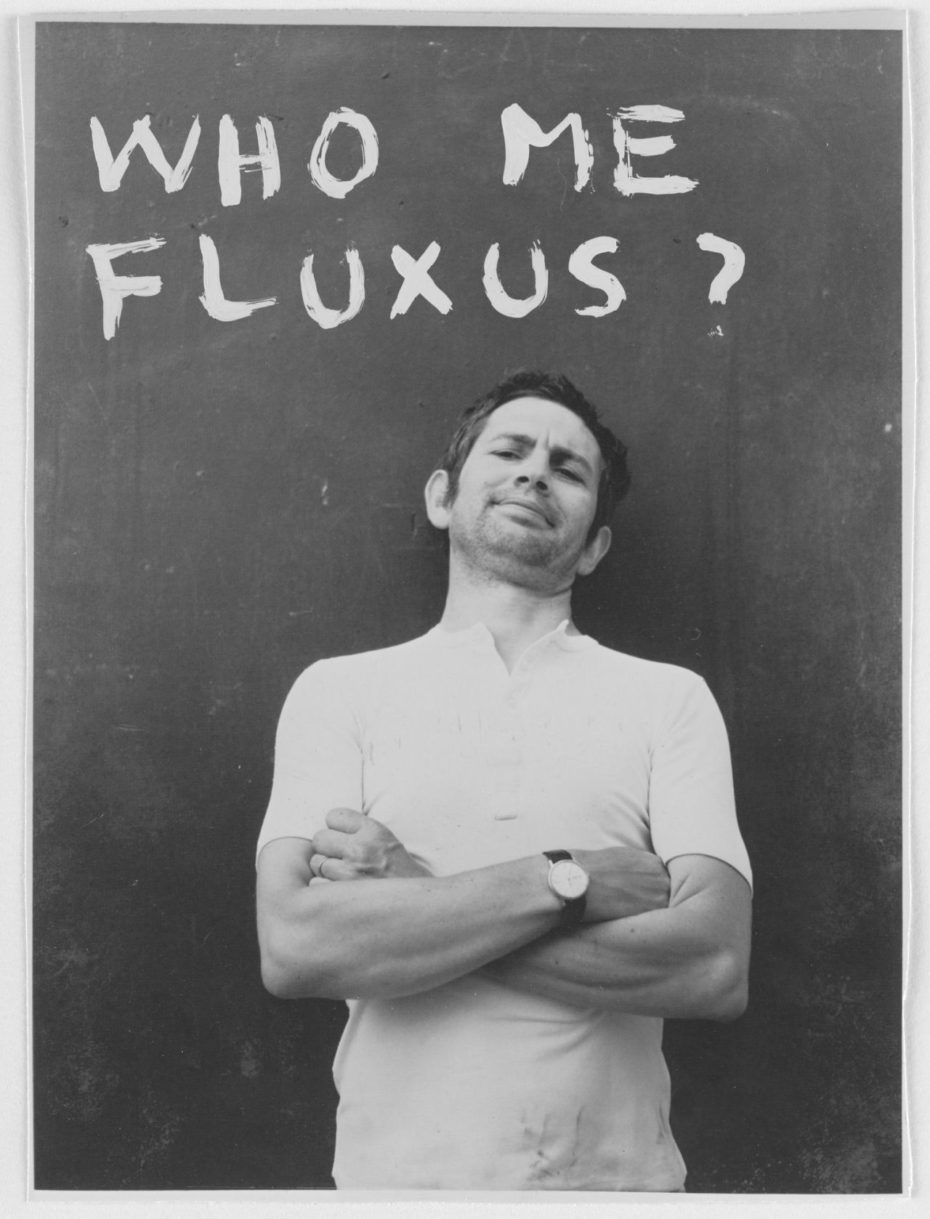

George Maciunas was a Lithuanian-American artist and architect who trained at Cooper Union, the Carnegie Institute, and NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts before working for several architectural firms during the 1950s. He first used the term Flux as the title for a magazine he was attempting to launch from the Lithuanian Cultural Club of New York. Acting as the editor and publisher himself, Maciunas wanted to create an international, interdisciplinary quarterly that covered every aspect of the avant-garde, from cinema to nihilism, from events to sound poetry. Maciunas co-founded the AG gallery in 1961 in New York and began to hold events there, working with a circle of artists that included Yoko Ono, a core member of the movement.

In June 1971, the Fluxus artist George Maciunas threw a dim sum party in New York for guests including Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono and John Lennon, who became an honorary Fluxus artist, not just by virtue of his relationship with Yoko but for his Dadaist humor in own his lyrics, other writings, and drawings. The digital video footage of that surreal party, come to think of it, would make a great candidate for an NFT.

“Fluxus artists pushed art well outside of mainstream venues,” one writer notes in a piece for Artsy.net. “Their informal, spontaneous, and often ephemeral pieces were not only difficult to collect and codify; they were also sometimes hard to recognise as art. But museums and galleries eventually caught up and absorbed their work. So too did younger generations of artists, who continue to build on the freedom that the movement introduced into artmaking with their own work.”

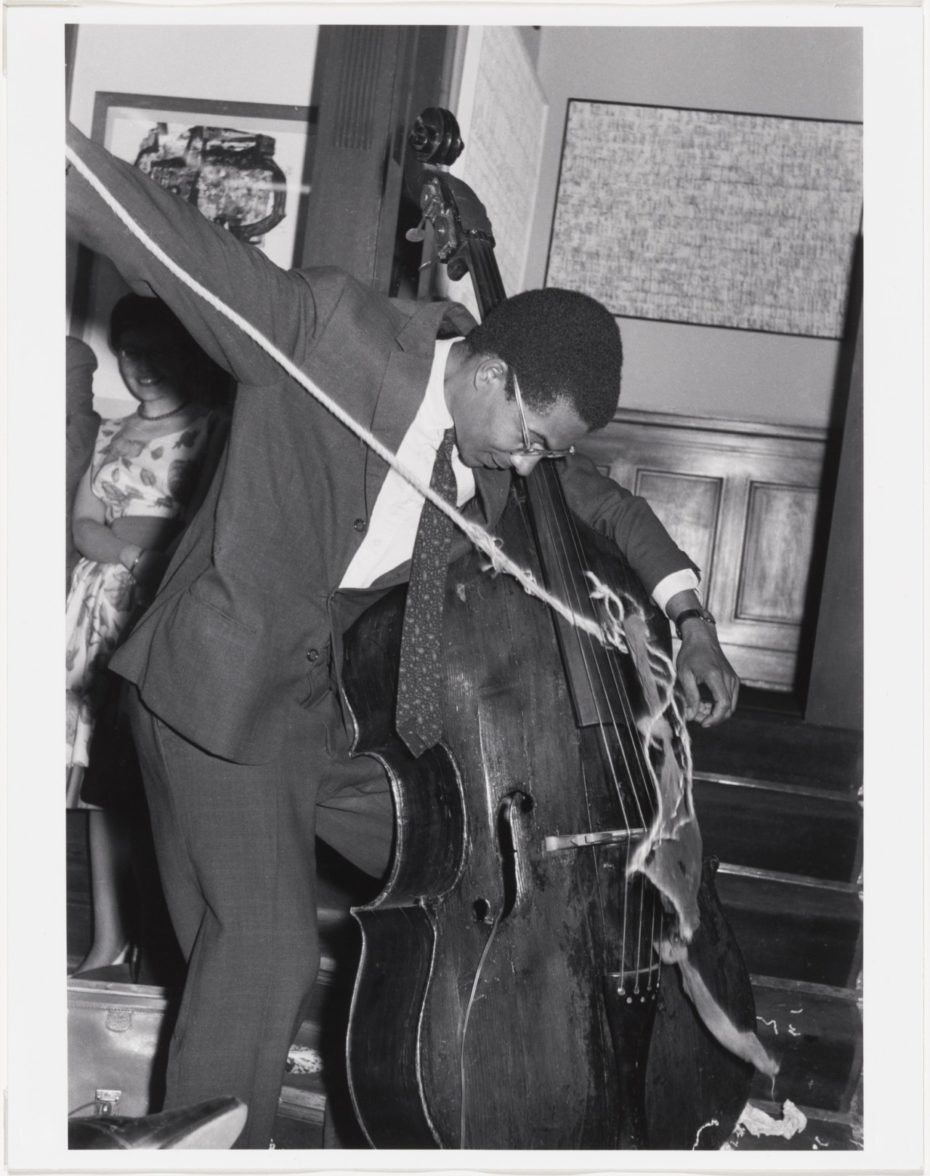

A major early event for Fluxus was the 1962 Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, or Fluxus International Festival of Newest Music. The festival consisted of 14 concerts that spanned several weekends. The choice to hold the festival in Germany was partially due to the popularity of New Music there, as well as the many Americans living in Germany at the time, most of them employed by the United States military. This included Maciunas, who had arrived in Wiesbaden in 1961 in an attempt to flee from debt collectors.

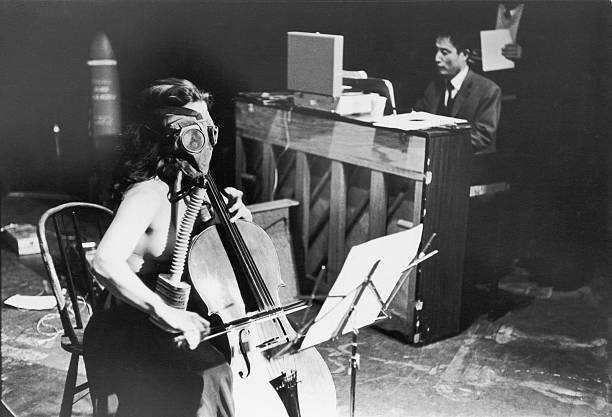

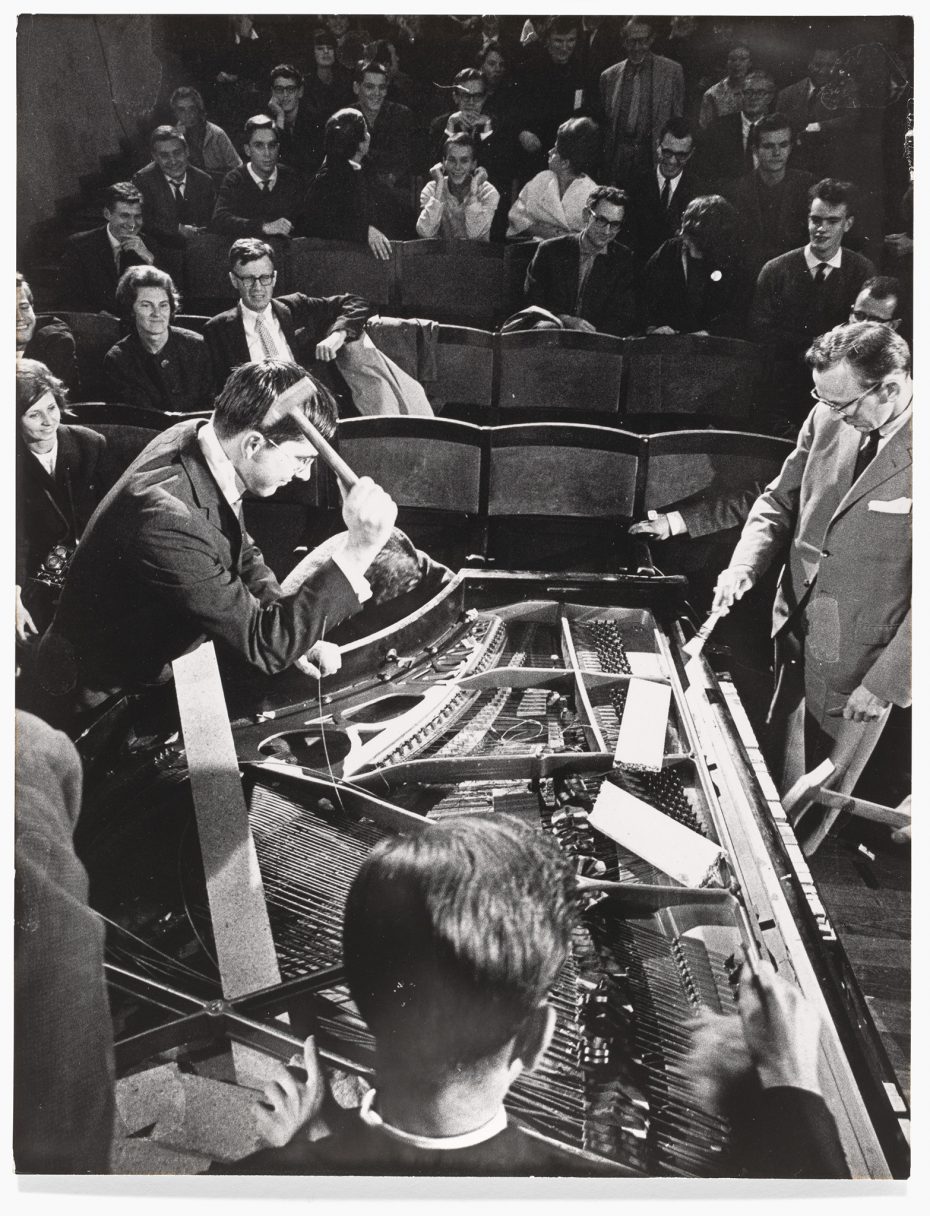

The most famous performance of the festival was Piano Activities, a composition by Philip Corner. Conceptually, the piece explores the sounds that can be made with a piano without touching the keys. Maciunas and several other artists scratched, struck, and eventually destroyed the piano. The work shocked the German public, ultimately raising the international profile of Fluxus and its members.

John Cage is often cited as an important influence on the Fluxus sensibility; Maciunas took great interest in the work of the experimental composer best known for his work 4’33”, which was performed in the absence of deliberate sound. Another inspiration was Marcel Duchamp and the Dada movement.

Maciunas would sometimes refer to Fluxus as Neo-Dadaism, a revival of the movement that thrived in Europe during the 1910s and 20s. Both Cage and the Dadaists shared similar sensibilities with Fluxus, chief among them, the rejection of traditional perceptions and presentations of art, exemplified through Cage’s silence filled symphonies and Duchamp’s “anti-art” ready-mades such as his famous “Fountain” and “Bicycle Wheel”.

Yet the origins of Fluxus were far different from those of Dada. In an interview, Fluxus artist Dick Higgins describes how, although their aesthetic and political sensibilities overlap, Dada began with an idea, followed by the work, while Fluxus emerged out of a group of artists already creating the work. Fluxus is more complicated to pin down and define than other artistic movements. In fact, “Fluxus network” seems a far better term for the style than “Fluxus movement”, for although artworks by Fluxus artists sometimes share a physical aesthetic, what was most important to the artists was the process in which they were made. Indeed, a cornerstone of Fluxus art is the concept that the process is prioritized over the product.

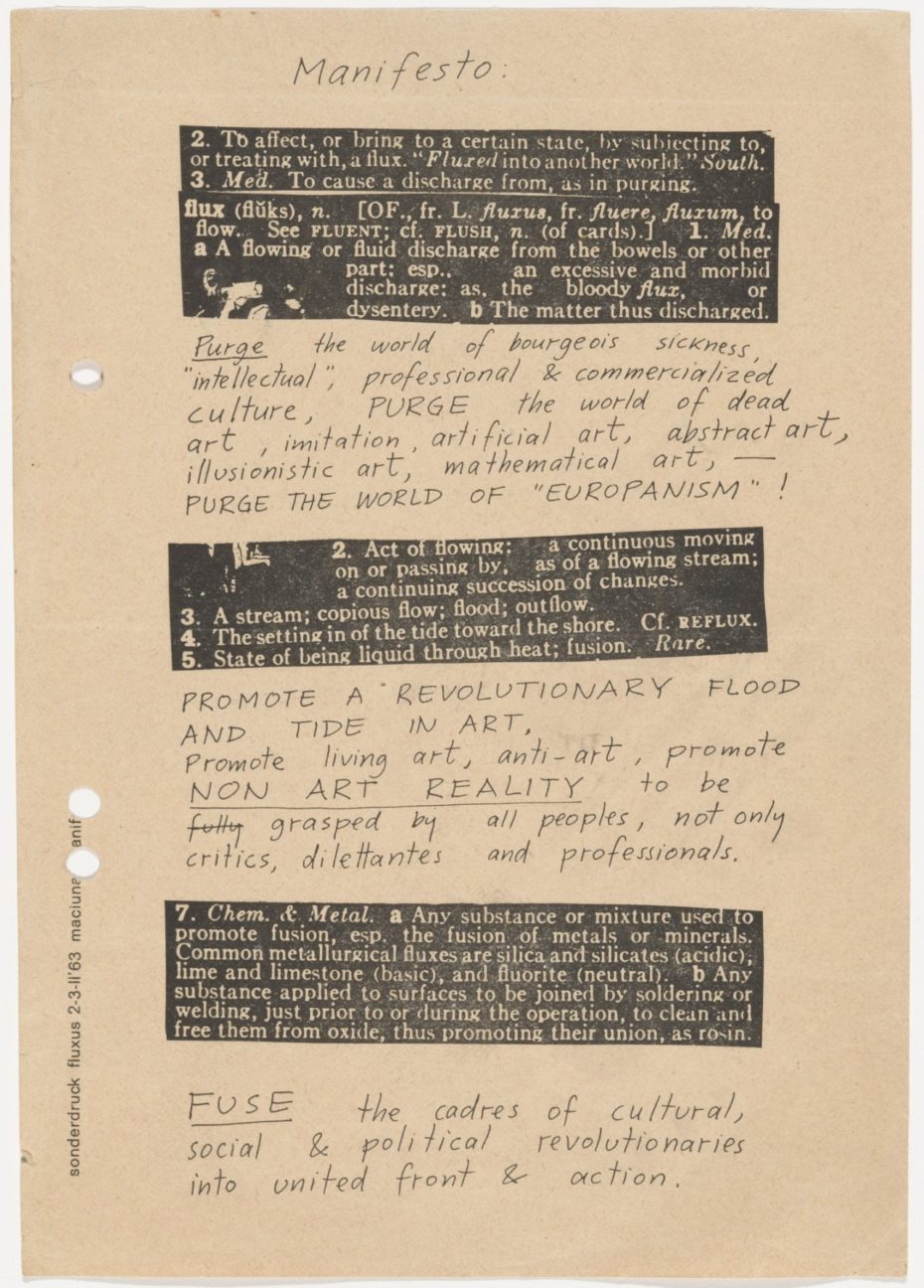

In 1963 Maciunas published the Fluxus Manifesto, clarifying that the objectives of the artistic movement were to “promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promote living art, anti-art, promote non-art reality”. In a nutshell, this was art intended to eradicate a high brow view of art that so often alienates the ordinary person. It was the idea of making art from everyday experiences and what it meant to be human; putting on events and performances in the streets and getting the public involved.

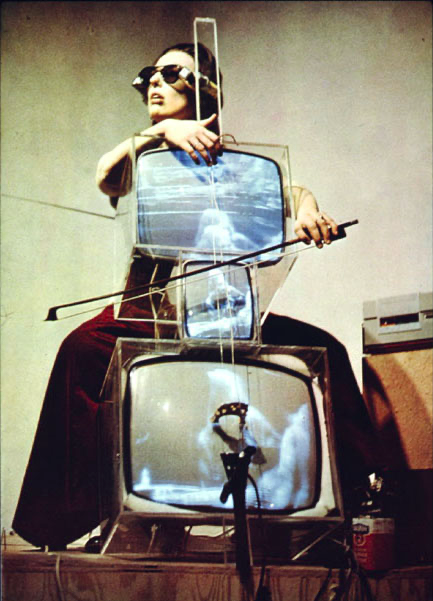

Within the Fluxus circuit, events were known officially as “Happenings”. Behind many of these Happenings in New York, Paris, Berlin and beyond, was Germany’s most dedicated Fluxus artist, Wolf Vostell, who was also the first artist in art history to integrate a television set into a work of art. He also took his art to the streets, testing the public with his radical Fluxus ideas. Here is his 1968 Happening on the H-Bahn, a suspended, driverless passenger suspension railway:

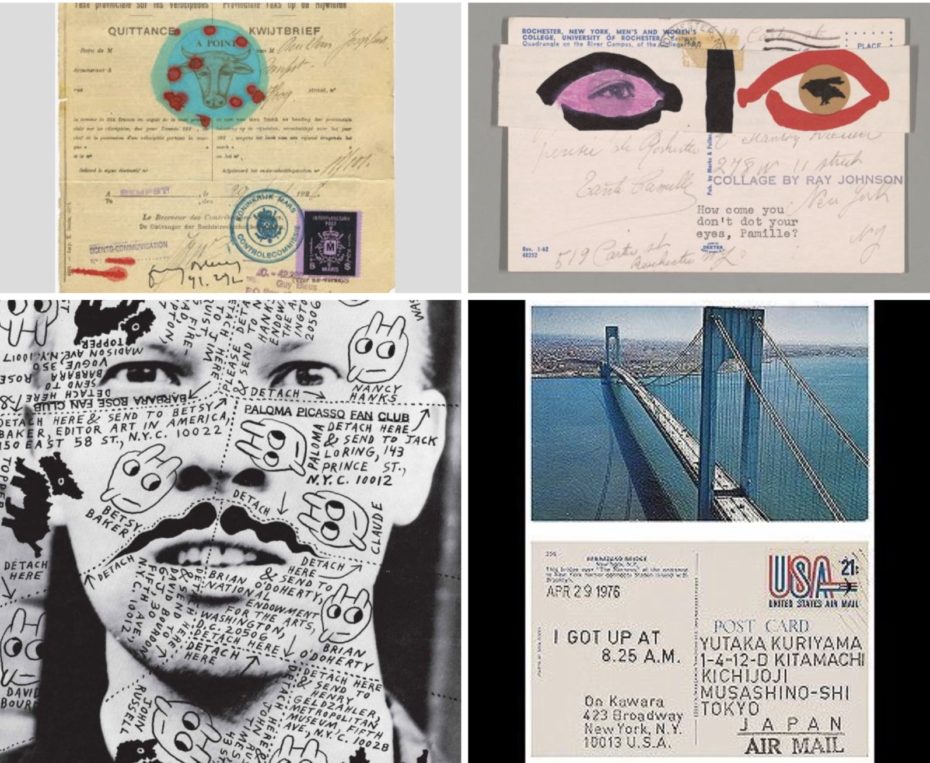

Along with video art, conceptual art and intermedia art (inter-disciplinary art activities), mail art also developed out of the Fluxus movements of the 1960s. The artistic movement centered on small-scale works, postcards inscribed with poems or drawings, and sending them through the postal service rather than exhibiting or selling them through conventional commercial channels. The mail was considered art once it was dispatched. Fluxus artists had also been involved since the early 1960s in the creation of artist’s postage stamps, spawning a vibrant sub-network of artists dedicated to creating and exchanging their own stamps and stamp sheets. Artist Jerry Dreva of the conceptual art group Les Petits Bonbons created a set of stamps and sent them to David Bowie who then used them as the inspiration for the cover of the single “Ashes to Ashes” released in 1980.

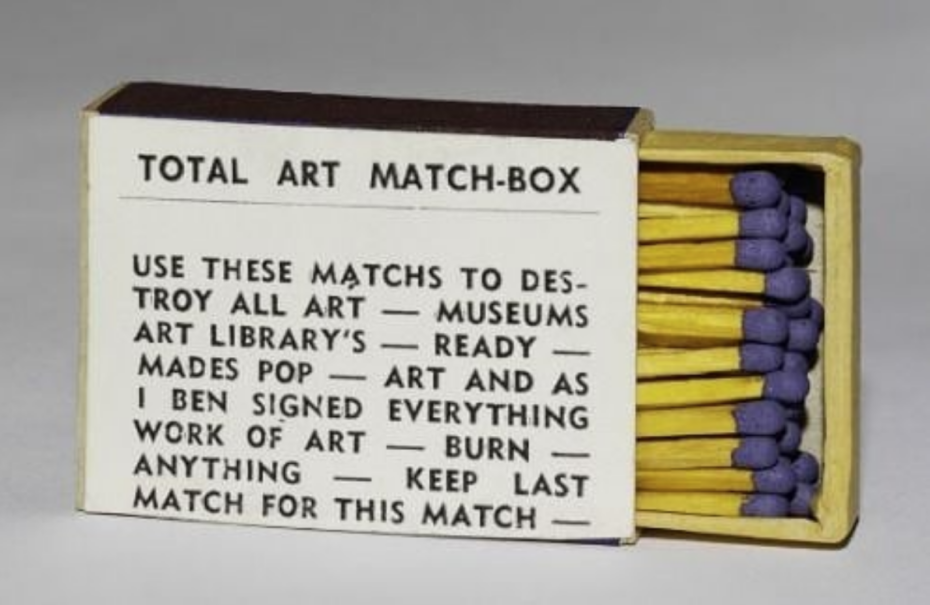

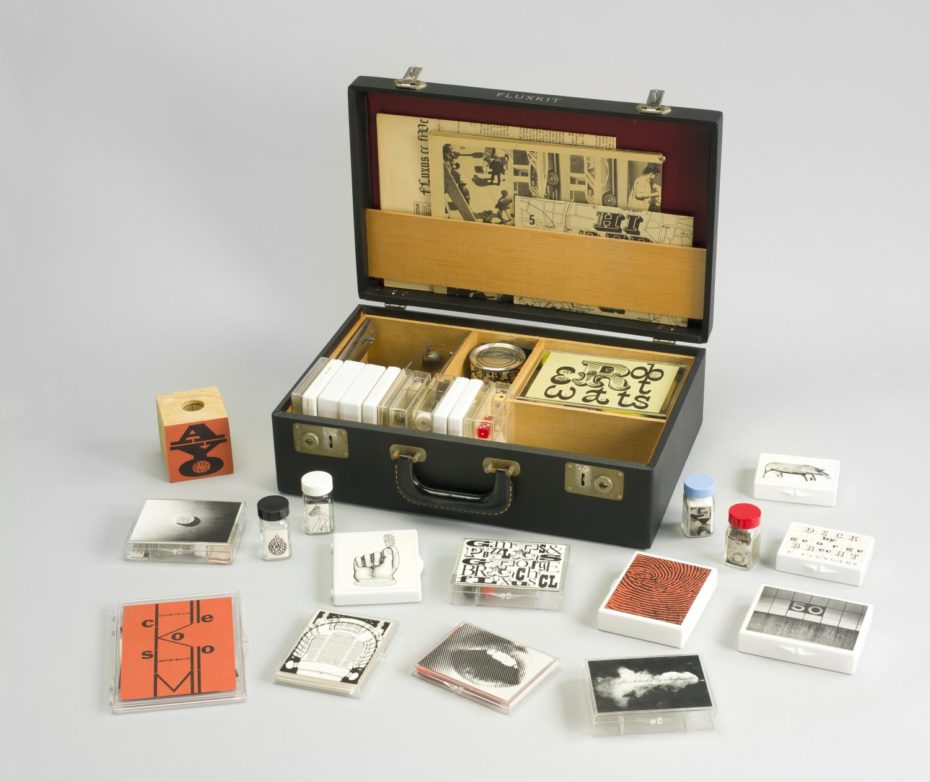

Around the same time as the new music festival, Maciunas began producing a series of game-like kits called Fluxboxes or Fluxkits, in unlimited edition that were small assemblies of objects meant to create Fluxus art with, for example, a briefcase containing a noisemaker, a Fluxus newspaper, a film, a game, or another type of art object. Each element was produced by a different artist. The goal of the Fluxkits was to democratise art and to allow anyone to participate. The Fluxkit rejected any ideas of authenticity or authorship, instead celebrating collaboration, mass production, and accessibility.

For the fifteen years, before his early death, George took on a plethora of projects in New York, from housing cooperatives to films, anthologies, events, and even a Flux chess set. Though Fluxus doesn’t have a definitive endpoint, the movement was considered to be over after the death of Maciunas in 1978. The events surrounding Maciunas’ funeral are often classified as the last Fluxus events. Called the “Fluxfuneral” and the “Fluxfeast and Wake”, artists performed, mourned, and only ate food that was white, black, or purple. Only months before, when it was clear Maciunas would soon die from pancreatic and liver cancer, he and his collaborators held a “Fluxwedding”. Maciunas married his long time companion, poet Billie Hutching. The bride and groom switched outfits midway through.

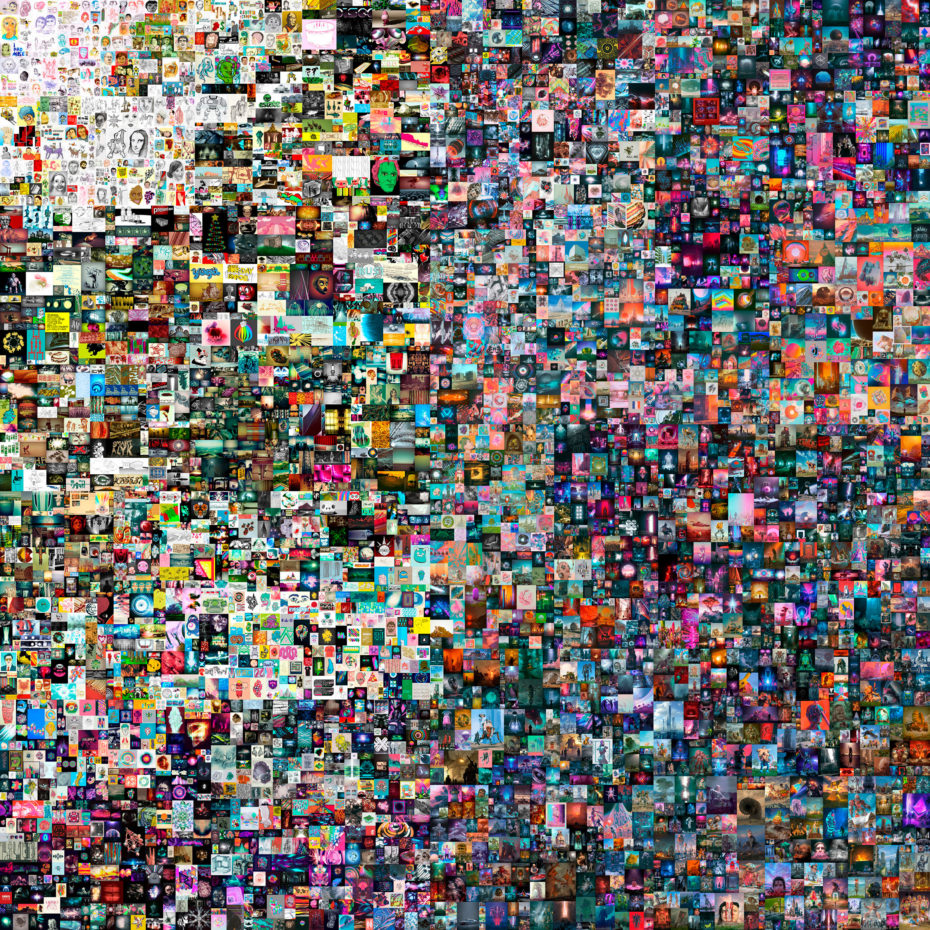

Half a century later, the Fluxus network is still in place, exemplified by contemporary artists who continue to practice Fluxus values. From an art historical standpoint, a line could be drawn from Dada to Fluxus to Andy Warhol’s factory, to street artists like Banksy and ending today with NFT crypto art. Consisting of a digital artwork verified and authenticated by blockchain, NFTs can be anything from a collection of pixels to a JPEG image to a screenshot of a tweet (Twitter founder, Jack Dorsey’s first tweet sold as an NFT for an oddly specific $2,915,835.47). While some critics remain skeptical about the artistic value of works that are entirely virtual and intangible, others, like Jerry Saltz of New York Magazine, have been quick to jump onboard and give NFTs the blue-chip endorsement leading to bidding wars at prestige auction houses. After breaking records in March for their $69 million sale of Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 5000 Days”, Christie’s listed a sale of digital pieces by Andy Warhol, bringing with it a fierce debate about authenticity within the world of digital art. Gucci held an auction ending on June 3rd of an NFT drawn from a video used in their Fall/Winter 2021 show. Sotheby’s joined the trend with a sale in April of NFTs from the artist known as Pak, that sold for over $16 million, quickly followed by the creation of a virtual gallery called Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale” which netted a total of $17.1 million.

Artists producing NFTs carry a spirit akin to that of the Fluxus artists, seeing themselves as figures on the cutting edge of both technology and art, challenging what art can be. Seen in the work of Beeple a.k.a Mike Winkelmann (the most financially successful and well known NFT artist so far), crypto art often shares an absurdist, irreverent tone that calls to mind Fluxus pieces like Piano Activities. Both movements reject art history by valuing process over finished product. Both criticise their respective political environments through satirical imagery and symbolism (see Beeple’s “sweet god I hope this picture stands the test of time“). Of course, Fluxus never had the market NFTs have – crypto art is intrinsically linked to buyers with millions in cryptocurrency and few places to spend it – yet the sensibilities remain the same. In an interview, NFT artist Beeple is asked about his artistic inspirations and replies “I’m going to be honest, when you say, ‘Abstract Expressionism,’ literally, I have no idea what the hell that is.” It’s hard to not hear the echos of George Maciunas, who, when asked to define Fluxus, was known to play recordings of dogs barking or geese honking.