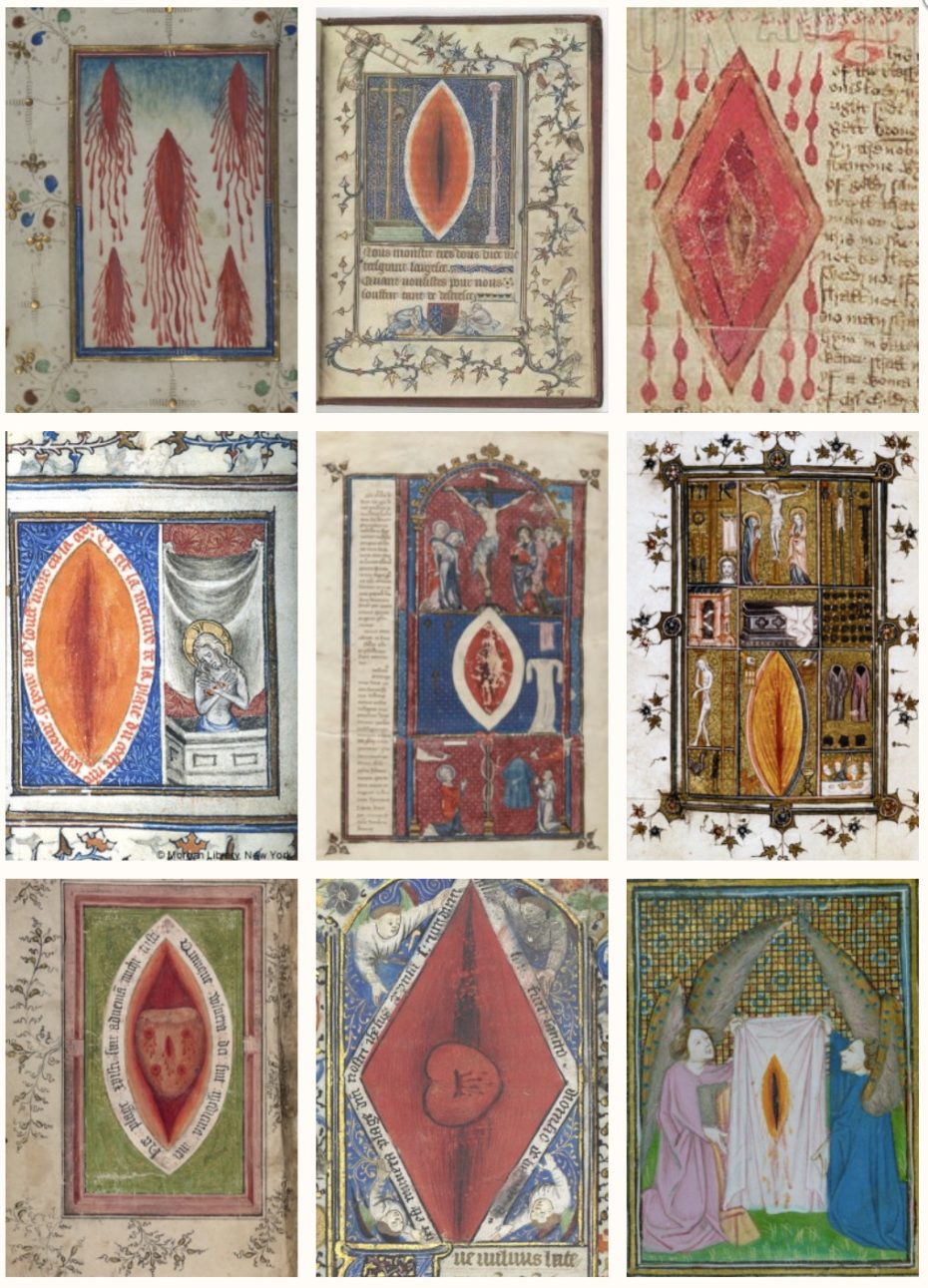

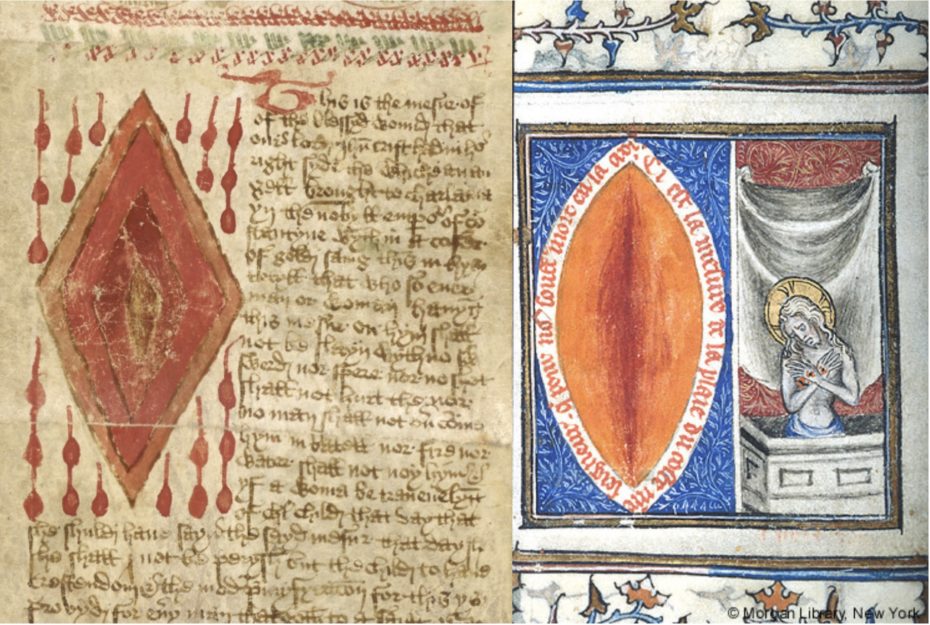

Let’s say you’re flipping through a medieval Christian prayer book (as you do), and suddenly you come across a curious illustration amongst the prayers and psalms of something that looks unmistakably like female genitalia. A scolding voice in your head tells you to get your mind out of the gutter. But you wouldn’t be alone. That fleshy full-page depiction of Christ’s wound really does like a giant vulva. And it turns out, Christian devotional texts are full of them.

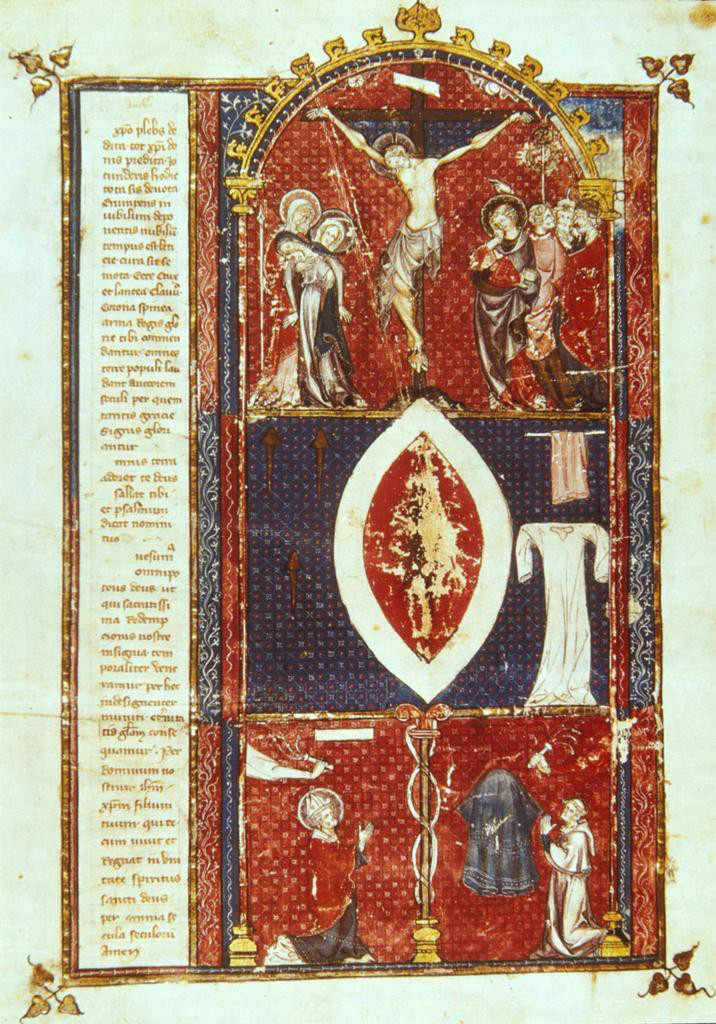

The Books of hours were the most popular books for laypeople in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, but in a time before the printing press, wealthy patrons also commissioned bespoke and visually pleasing prayer books by leading artists. Tens of thousands survive today, largely dating between the 13th and 16th centuries, containing sets of prayers to be performed throughout the hours of the day and night. It’s common to find artwork portraying his Five Holy Wounds, the fifth caused by the Holy Lance (otherwise known as the Lance of Longinus), which pierced Jesus’s side as he hung on the cross. Fleshy and brightly coloured, a fair number of them might not look out of place in a particularly sensual Georgia O’Keeffe painting.

They evoke the shape of a mandorla (the Italian word for almond nut), an oval that often encases Christ or the Virgin Mary in iconography of this period. Co-Author of Solus Jesus: A Theology of Resistance, Emily Swan wrote, “Medievalists speculate that the wound, pictured as a slit in Jesus’s side emitting blood and clear liquid, led some mystics to imagine other bodily slits that emanate blood and clear fluids.” Religious scholars have debated their significance over the years. In fact, a growing field of scholarship focuses on how these depictions represent a more queer and erotic understanding of Christianity and the story of Jesus Christ.

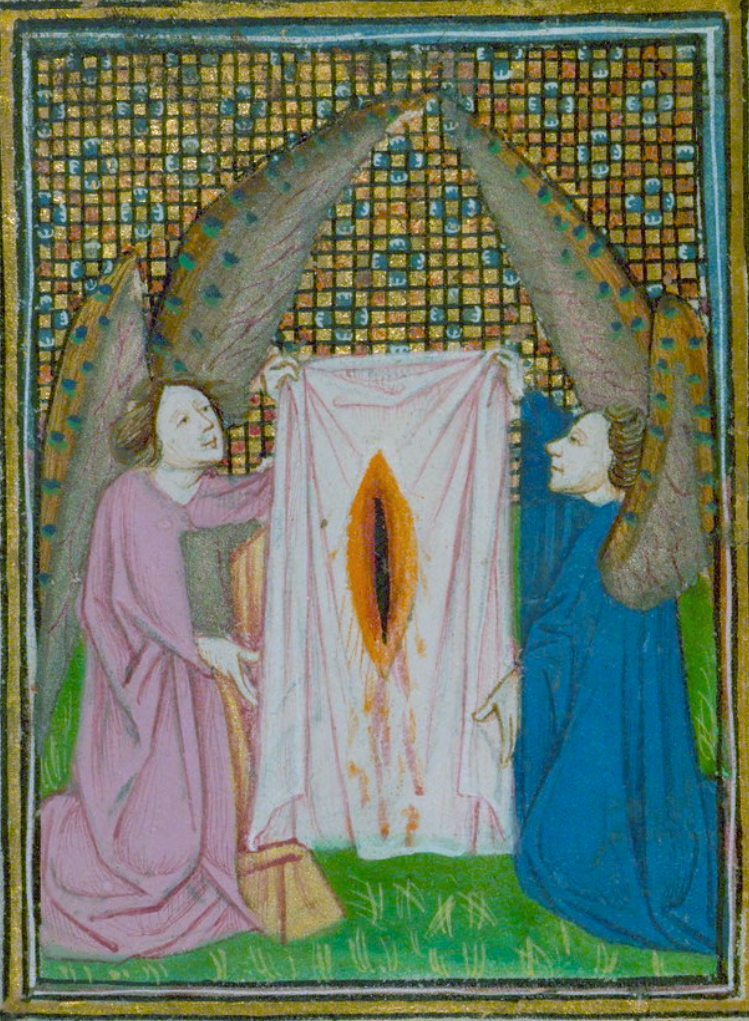

Swan goes on to explain that Christ represents life-giving with his resurrection, not unlike female reproduction. Who’s to say those liquids weren’t intended to represent breast milk, menstrual blood or amniotic fluid from giving birth? Many scholars in fact have connected childbirth to Christ’s birthing of the Christian Church. “The idea of Jesus’s side wound being like a womb then led to artists showing a female — either baby or adult — being birthed from that wound,” says Swan. This late medieval tradition of depicting Christ as a motherly figure came about during the rise of female mystics like Catherine of Siena, who received the stigmata before dying.

Independent curator Liz Lorenz described this era in the visual arts as a shift toward the macabre, when “Christ’s humanity became more important, and his suffering was illustrated by an emaciated, gnarled body with contorted bones and bloody gashes.” This so-called affected piety became central to religious devotion. And by deconstructing his body, the “symbols of his pain directly confront the reader,” wrote Lorenz. Of course, as Lorenz also pointed out, the “trauma and voyeurism” in viewing the wounds embodied as feminine reproductive organs is not disconnected from the fate of many female bodies, commonly tortured and mutilated as both heroines and heretics.

Many have also argued the wounds represent a sort of gender-fluidity of Christ as the embodiment of the human race. This is a departure from the many depictions of him with predominantly masculine traits. In fact, the female reproductive organs were often associated with the hellmouth (or the jaws of hell) and some even viewed the original sin as being transmitted through the vagina.

Consequently, Martha Easton, one of the predominant voices on Christ’s wounds, described them as a potential reworking of the “negative associations of the female body prevent in medieval religious, social and visual culture.”

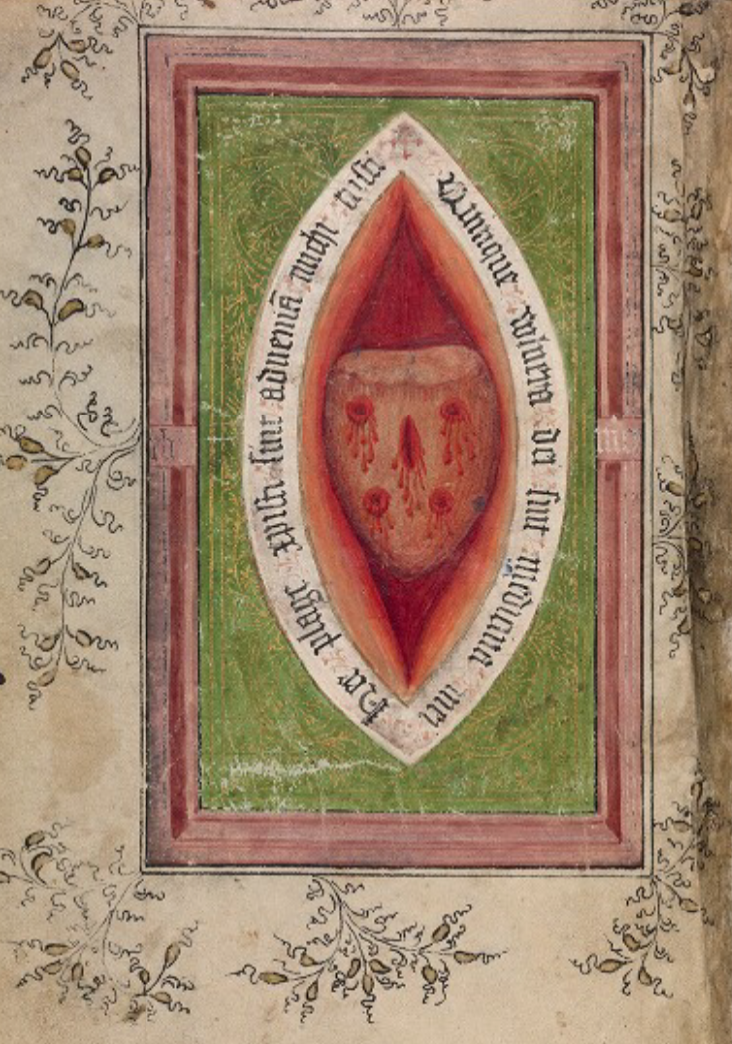

Many Christians in medieval Europe felt a strong personal connection to this imagery. The vulva-like drawings were rolled up and tied to the body in order to prevent illness and sudden death, wrote Sophie Sexon, a Ph.D. candidate studying the wounds in late medieval art, particularly through a queer lens. In a piece for History Matters, Sexon wrote that the wounds were commonly encircled with an inscription reading that this was the “true measure” of Christ’s injury, and they were meant to be prayed, touched and even kissed. Often in these surviving illuminated manuscripts, it’s been found that the pigments are worn away on depictions of Christ’s wound and sometimes, even the paper has been ripped through the length of the cut. Given that the books of hours were often made with vellum (AKA calf skin), there is an even stronger sensual connection.

“There are a variety of medieval accounts of people becoming aroused by images of Christ,” wrote Sexon, adding, “As those rubbing or touching these vulva-like images in manuscripts would have been people of all genders, there is a certain queer history to be uncovered in this erotic and sensual encounter with the skin.”

Sexon also pointed out that these aren’t the only example of female anatomy in iconography from this time. Architectural grotesques found throughout most of Europe known as Sheela na gigs are figurative carvings of naked women that protected buildings, including many churches, around the 11th and 12th centuries.

The figures had exaggerated vulvas, often held open by hands, and might have served to ward off evil spirits, similar to their grotesque gargoyle cousins. Pilgrim badges worn during pilgrimages to holy places sometimes featured vulvae and penises, including some with wings. Similar to Christ’s wounds, the meaning of these pilgrim badges has been debated, with some describing them as “heathen” medieval jokes and others connecting the vulvae imagery in particular to hopes of female fertility.

Christ’s wounds and these other symbols are fodder for further exploration, given that they have been largely overlooked or dismissed by more prudish researchers of the past. Some art historians like Martha Easton are skeptical, wondering whether femininity is lost in the appropriation of vulva: “When the bodily, the oral and the vaginal, constructed by the dominant culture as feminine, are subsumed into Christological discourse, where does this leave real women?”

Liz Lorenz sees potential in this imagery, both historically and today. “The fascination with and fear of the female form is a longstanding truth of the human, especially male, psyche… Illustrations of these suggestive wounds assert the undeniable force of the female form to fascinate and evoke awe. By activating and asserting what is unique to them, women’s bodies have been and will continue to be a focus of representation, contemplation, and inspiration.”