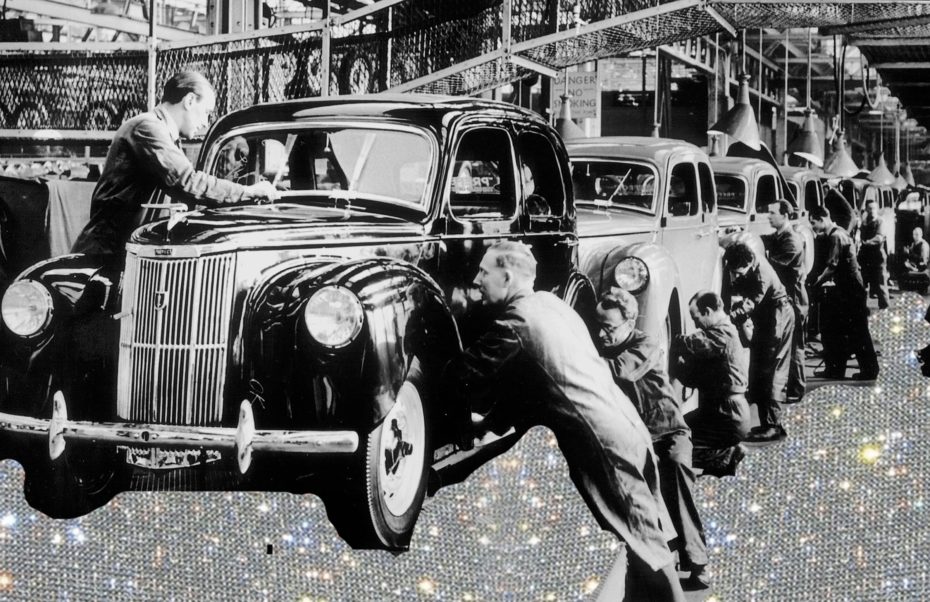

What’s more finite and limited than diamonds? Surely not something found on the skids of an old car factory? Well get this: in the 1940s, the American automobile industry started painting cars with a hand-spraying technique that would accumulate overspray, which would build up and be baked repeatedly in ovens to cure the paint on the vehicles. Keen-eyed assembly line workers at Ford and other car manufacturers recognised the aesthetic value of these paint clumps and began to salvage, cut and polish them for jewellery. The dried paint stones came to be known as Fordite, and could be found on factory skids until the 1990s. Those car painting techniques however, are no longer practiced, making authentic “naturally occurring” Fordite a rare commodity. Their history makes them almost as valuable as real gems – and that value can only increase with time. Collectors, do we have your attention?

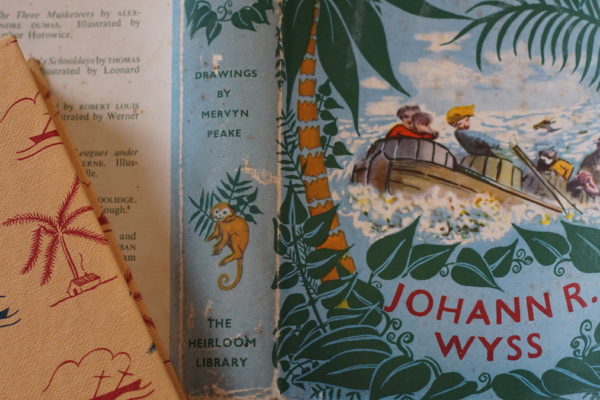

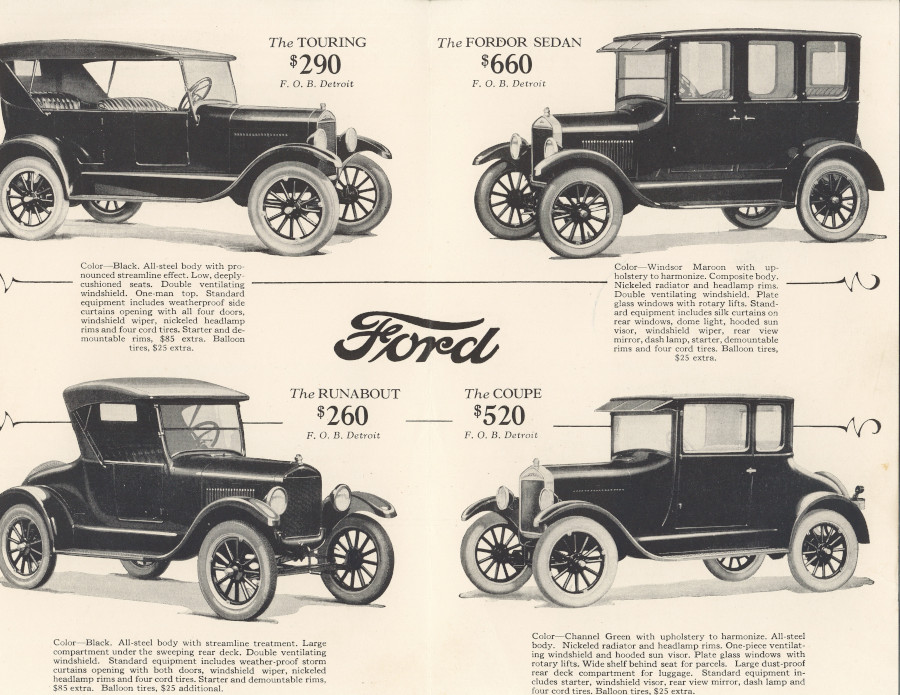

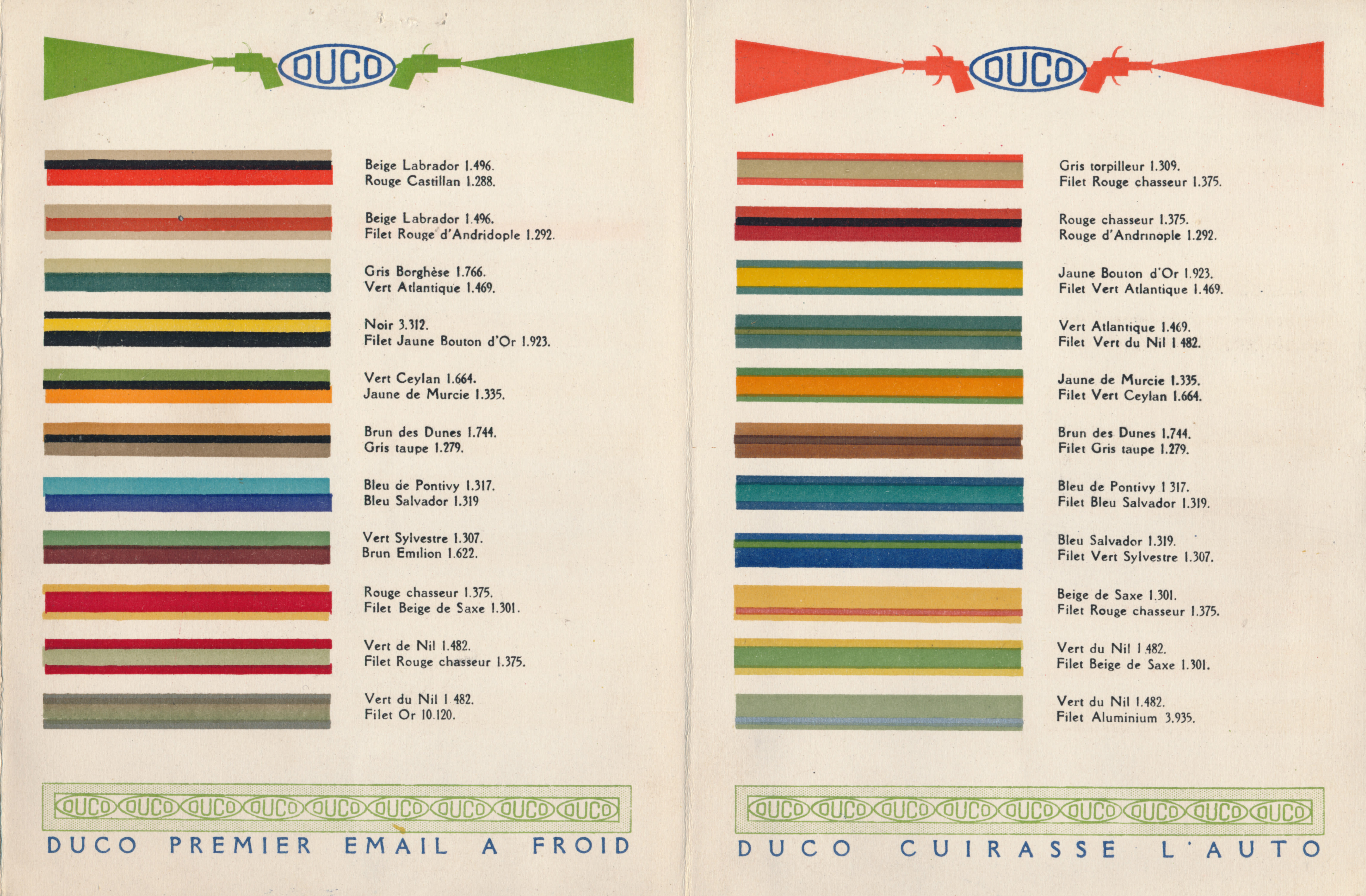

Henry Ford once said, “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants, so long as it is black.” For many years, the famous Model T only came in black because the production line required compromise for efficiency and improved quality. In the early days, paints couldn’t stand up to time because there was no binding medium, which meant that whatever color it was originally would end up turning yellow. Dark colors simply lasted longer and didn’t take as long to dry. The use of asphalt enamel was more efficient, but it certainly had its drawbacks, including requiring a huge amount of space and “nary a stray bit of lint or hair to mar an otherwise perfect paint job.” The painters would even paint naked to avoid the potentiality of affecting the finish. But as demand increased and technology developed, so did the colors and models of the vehicles. The colors got bigger and brighter in the peacetime after the Great War. The classic Fords of the 20th century in Polynesian Green, Clover Green Pearl, Deep Maroon 347 – they all got to be those colors by a tedious, complicated, and expensive procedure done by hand.

With the Great Depression in America, and the market crash of 1929, colors dimmed to greens and grays… and when cars were colorful, the fenders were usually painted with the black asphalt paint to save on repairs later. Even so, the 1930s did see the addition of metallic paints, and they were at first made with actual fish scales (we’re talking 40,000 herring to make one kilo of paint). That was very expensive, so American paint companies used aluminum flakes in their metallics to save on costs… but they did pay homage to their predecessors with colors like “Fish Silver Blue.”

Nowadays, car painting techniques are largely automated, with notable exceptions, but from the 1920s to the 1980s, all these cars were painted by hand. The hand-spraying technique would accumulate overspray in the paint bay, and because the car paint had to cure in an oven, these paint clumps would harden, too. Eventually, they got in the way of the process, so they had to be removed.

Though it’s not certain who exactly discovered the beauty and potential of Fordite, lots of people hypothesize it was probably someone hired to clean the bay itself who salvaged the clumps when they became obstructions. When cut open, they found what was basically an industrial geode.

Some clumps of Fordite were fired as many as 100 times due to the paint curing process, which makes them fairly durable, for being paint clumps. Once polished, the clumps reveal themselves as gorgeous stones, reminiscent of agate. In fact, a common name for Fordite is Detroit agate or Motor City agate, because of Detroit’s history of car manufacturing. A subset of Fordite that comes from the Corvette assembly plant in Bowling Green, KY is often called “corvetteite” — and Lincoln-Mercury paint from a Canadian plant.

As you can see, the colors ripple in a vibrant, psychedelic effect, and workers quickly realized the aesthetic value of the dried paint stones. Because Fordite is no longer a byproduct of the auto industry, the stones’ rarity and value has increased dramatically.

Fordite.com says there are four types of Fordite itself:

Type 1: Separated Colors- Regular grey banding of primer layers between color layers.

Type 2: Color on Color- Opaques and metallics. Limited colors. Small parts and special color runs.

Type 3: Color on Color- Drippy and/or striped, with multiple color on color layers with metallics … sometimes containing lace and orbital patterns, with occasional surface channeling.

Type 4: Color on Color- Opaques and metallics, with bleeding color layers, sometimes containing pitting from air bubbles as the layers formed and hardened.

Of course, the brightest colors come from Fordite salvaged in the 1960s and 1970s, since that’s when the demand for brightly colored cars was its highest. Earlier on, Fordite came in more neutral hues.

According to one fashion report, the brand Roland Mouret liked the pieces so much it used several in its New York Fashion Week presentation…including Marla Aaron’s statement earrings” (pictured above). “Aaron said the brand was so taken with fordite that it had the nail artist create a pattern to match.”

The material is so light that Fordite earrings of a considerable size won’t pose the kind of headache that a naturally-occurring stone might.

Of course, there are stones that replicate the vivacity, but authentic Fordite is hard-won and now very valuable… as valuable as some real gems. There’s even a recommended way to care for the jewellery itself. Experts say to use warm, soapy water, but like other soft materials, light scratches occur with frequent wear. In that case, the experts recommend a care routine that’s not so different from polishing one’s car: “Use a fine car polishing compound like Turtle Wax, and buff to a high shine with a soft, 100% cotton cloth, or just green jewelers rouge.” But of course!

By the 1980s, car manufacturing had moved away from the hand-spray painting method, but workers say the stone could still be found on the skids at factories in the 1990s. Now, manufacturers use an “electrostatic process that magnetizes the enamels to car bodies,” which eliminates the overspray, or at least constricts it significantly. Authentic Fordite has now achieved a nearly collectible-level status, especially with the supply being limited to what’s already available on the market.

One collector, Mr. Baskin, is also hunting for fordite from Harley-Davidson motorcycles to “fulfill the appetite of Harley lovers.” Another article suggests that Fordite is rare enough to be counterfeited, as well.

You can buy authentic Fordite from twenty to hundreds of dollars on eBay or Etsy today, depending on its size, type, and rarity of the paint colors contained within it.

The most valuable takeaway from the Fordite story, though, is that the workers at these plants noticed an analogous beauty. Whereas classic cars have long been appreciated for their gorgeous designs, the manufacturing workers found beauty where most people would see only waste. By recycling the overspray, not only do we get to see an artifact of a bygone era that might be truly gone forever, but they also turned what could have been considered trash into covetable beauty.