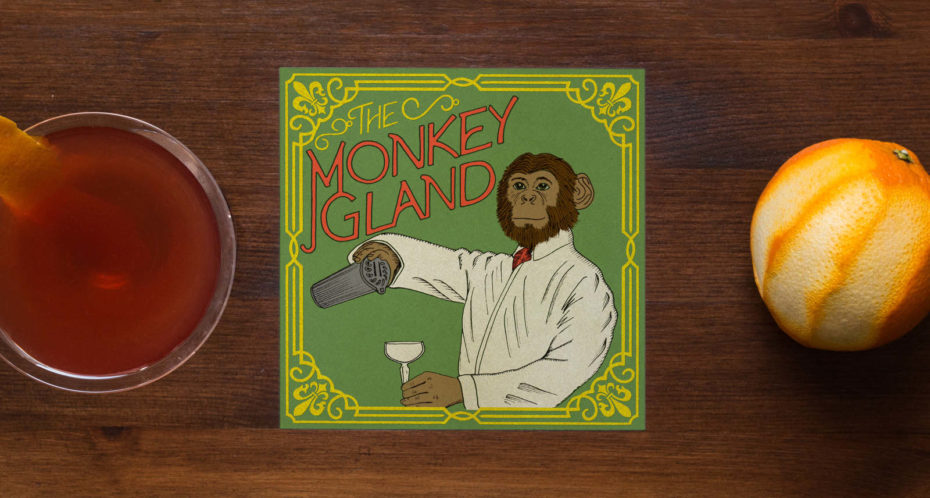

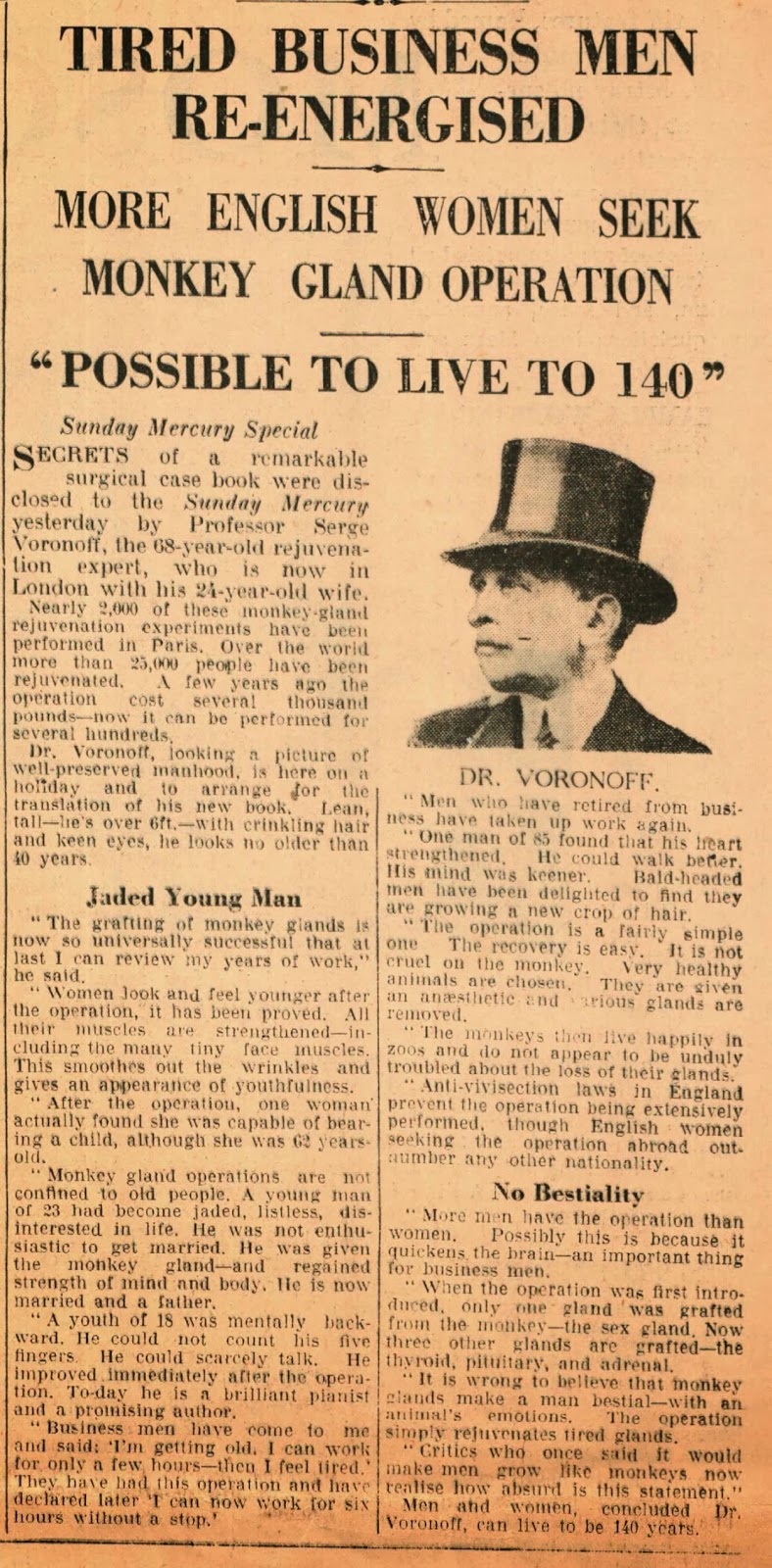

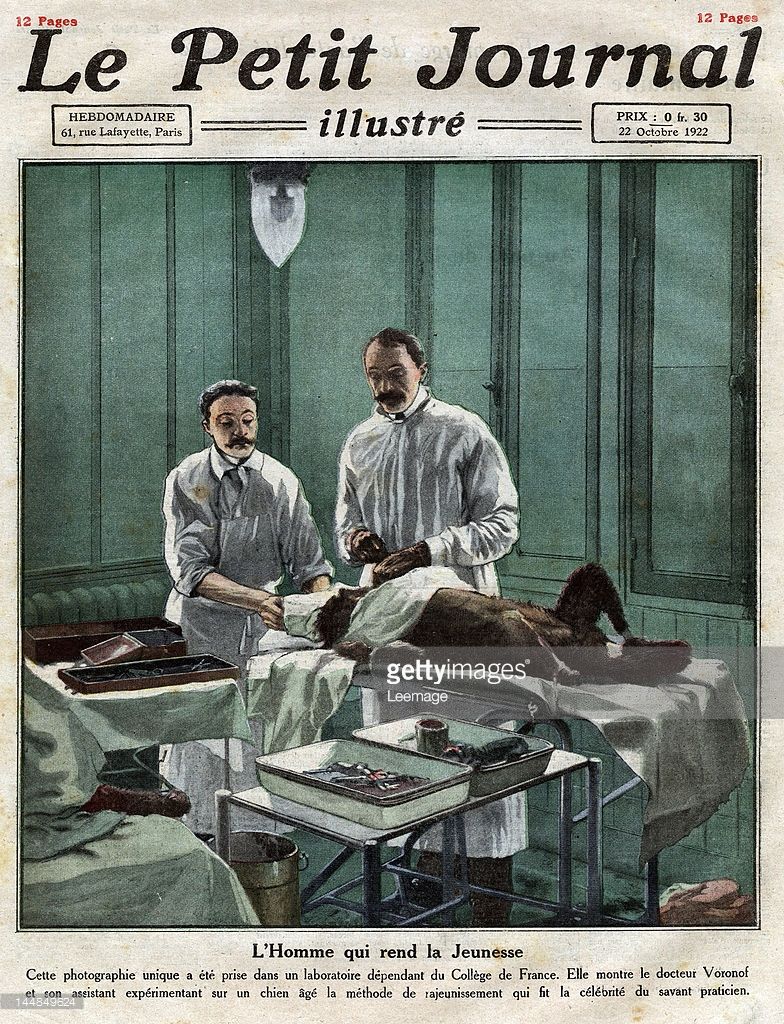

The poet E.E Cummings once wrote of a “famous doctor who inserts monkey glands in millionaires” and in a pre-code Hollywood musical starring the Marx Brothers, they sang the line, “If you’re too old for dancing / Get yourself a monkey gland” performing a number entitled “Monkey-Doodle-Doo”. There was a famous Chicago surgeon who wrote in his 1943 autobiography: “fashionable dinner parties and cracker barrel confabs, as well as sedate gatherings of the medical élite, were alive with the whisper – Monkey Glands“. And during the Jazz Age, a new cocktail containing gin, orange juice, grenadine and absinthe was invented at the Ritz Paris, called “The Monkey Gland”. All of this monkey business was due to one man, Doctor Serge Voronoff, who from Russia to Paris, from Egypt to the Italian Riviera, was famously known as the “monkey gland man”. In the 1920s, the Russian-born French surgeon who claimed to have invented an elixir of youth, a sexual stimulator and mental health cure-all by grafting monkey testicle tissue on to the testicles of men. Voronoff’s monkey-gland treatment became the talk of every cosmopolitan town amongst the early 20th century elite. And in a world where women are often stereotyped as the obsessive seekers of eternal beauty and youth, Voronoff’s strange story places men – very rich men – in front of the vanity mirror.

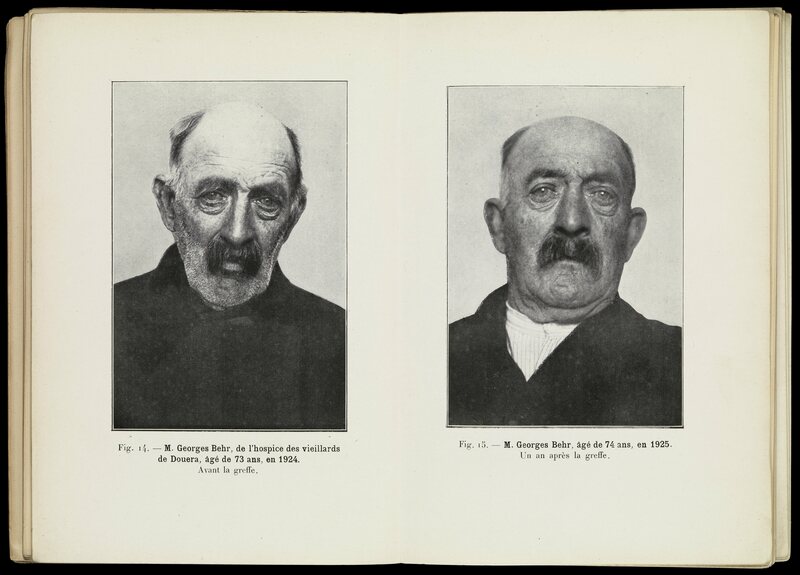

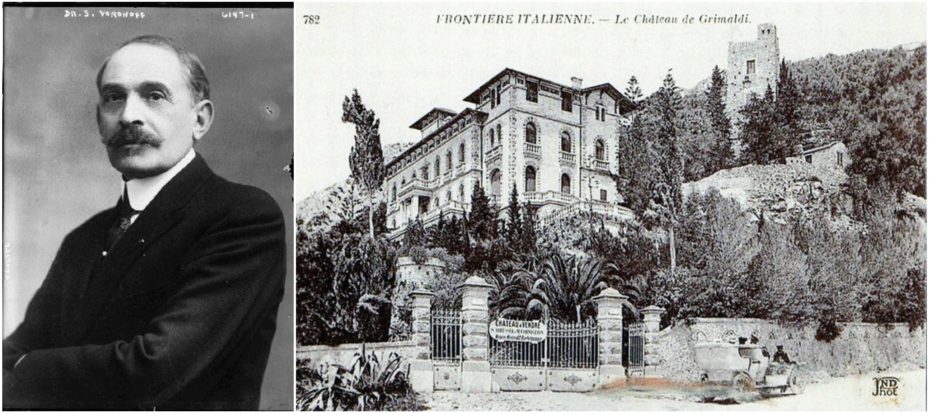

The first official transplant of a monkey gland into a human body was performed on June 12, 1920. Three years later, Voronoff’s work was applauded by more than 700 scientists at the International Congress of Surgeons in London. The transplantation of living cells, tissues or organs from one species to another had become a experimental trend in the field of medicine as early as the end of the 19th century. Around this time, Voronoff had been studying the effects of castration in Egypt, which would later inform his work on rejuvenating treatments. By 1920, he was conducting his first transplants between chimpanzees and humans. For a brief time, he was using the testicles of executed criminals to transplant into his wealthy clients, but when the demand eventually became too great, he had to open a monkey farm breeding facility on the Italian Riviera. During his career, Voronoff also performed testicular transplants on more than 500 goats, rams and bulls, claiming the results showed that implanting organs extracted from young specimens into older animals had a revitalising effect on the latter. He proceeded to convince himself (the world’s elite) that he had discovered a method to slow down the process of ageing.

Millionaires from all over the world applied for the operation, and by the early 1930s, thousands of people had gone under the doctor’s knife. Voronoff’s success led him to a life of luxury and extravagance. He occupied an entire floor of one of the most expensive hotels in Paris and had a personal entourage of chauffeurs, valets, personal secretaries and mistresses. His work had been funded since 1917 by a wealthy American socialite Evelyn Bostwick, who became his laboratory assistant in Paris before she became his wife in 1920.

In Voronoff’s 1925 book Rejuvenation, he described the many benefits of his treatments, which included an improved sex drive, better memory, the ability to work longer hours, improved eyesight, the prolonging of life and even speculated that his grafting surgery could be an effective treatment to senility, notably schizophrenia. In his later career, Serge turned his attention to his untapped market – women – and began experimenting with transplanting monkey ovaries into women.

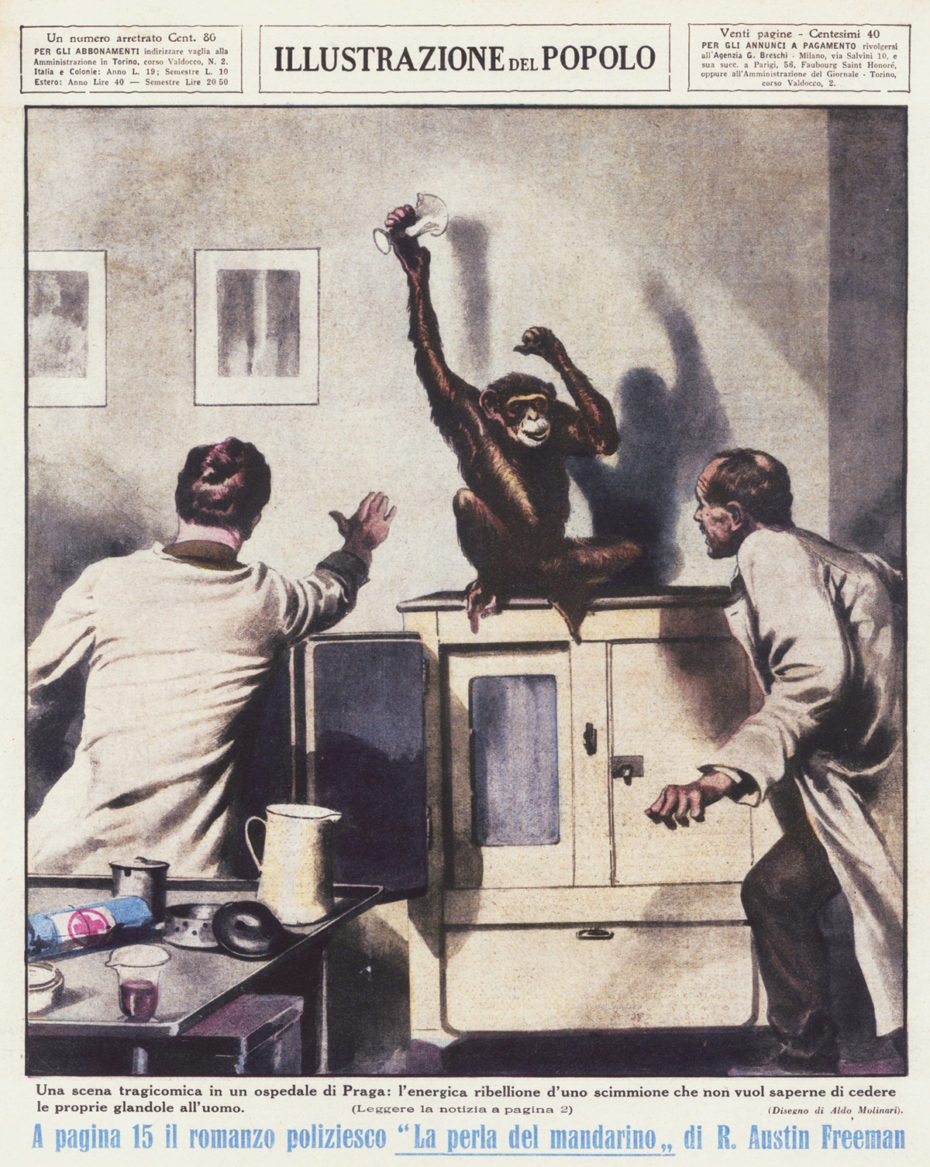

But he didn’t stop there. Voronoff notoriously tried reversing the process by transplanting human ovaries into a female monkey and even attempted to inseminate the primate with human sperm. Needless to say the experiment failed, but it did get immortalised in literature, inspiring the novel Nora, the Monkey Turned Woman by Félicien Champsaur.

Soon enough, the jig was up and Voronoff’s mad and monumental career as the “The Monkey Gland Man” came to an abrupt end by the late 1940s. Word quickly spread that his transplants were proving less beneficial than he had promised. An eminent British surgeon called Voronoff’s treatment “no better than the methods of witches and magicians” and soon enough, his treatments were widely considered to be pure deception. In Paris, there was even a novelty trend for ashtrays that depicted monkeys protecting their private parts, with the phrase “No, Voronoff, you won’t get me!” printed on them.

In 1986, transplant surgeon David Hamilton would clarify in his book, The Monkey Gland Affair, that animal tissue, when inserted in a human, would instantly be rejected – and only the scar tissue might fool a patient into believing the graft had been absorbed and was still in place. Experts put the initial improvements experienced by patients on the account of a placebo effect.

Some scientists in the 90s even accused Voronoff (posthumously) and his experiments of being the source of the mutation that allowed the AIDS virus to infect humans, but these claims were quickly discredited. Today, however, Voronoff’s insights into mammalian sex glands are considered to have led to great advances in modern endocrinology and biology, as well as hormone replacement therapy. His transplants on primates, however, are among the quirks of medicine that the world would perhaps sooner like to forget. But it sure makes for a good story over a Monkey Gland cocktail.