To the leaders of Communist East Germany, nothing was quite as dangerous and potentially subversive to their nation’s youth as Western rock and pop music. By 1965, Beatlemania may have been at its height with the band regularly attracting seventy million viewers on the Ed Sullivan show, but behind the Iron Curtain, the Party State leader of the GDR, Walter Ulbricht was less than enthused with the auditoriums packed with hysterical, high-pitched screaming fans. The hard line Communist and driving force behind the Berlin Wall famously declaried, “I am of the opinion, Comrades, that we should put an end to the monotony of the ‘Yeah Yeah Yeah’ and whatever else it’s called. Must we really copy every piece of garbage that comes from the West?” Fearful of bands viewed as decadent capitalist puppets spreading degenerate Western values and corrupting East German teenagers, the Rolling Stones were banned and the gyrating Elvis Presley ridiculed, his “so-called singing was just like his face: stupid, dull and brutish”.

The Berlin Wall may have created a brutal, physical barrier between East and West, but much like King Canute trying to stem the apocryphal tide, the GDR government could do little to control the airwaves, and a steady stream of Western rock music from stations like Radio Free Berlin, and Radio in the American Sector drifted over the Wall and into teenager’s bedrooms.

And so the ever inventive GDR government came up with a novel solution to clamp down on the popularity of Western music: they would simply create a whole music industry of their own. From the 1960s to the fall of the Berlin Wall, there existed an entire, somewhat peculiar parallel music industry in East Germany. But rather than simply mimic Western bands, the GDR government planned to create a music scene that would not only appeal to young East Germans but promote the lofty ideals of socialism.

To do this, the music industry would be, like virtually every other aspect of life in the GDR, highly state-controlled. Lyrics were censored, the notorious Stasi secret police would infiltrate bands, and groups deemed unacceptable would simply cease to exist, their records struck from history in pure Orwellian fashion. There was a kitschy Communist version of the Eurovision, called the Intervision Song Contest, and there was even a Socialist-acceptable teenage dance created by the State.

But despite the challenges of trying to create music amidst the confines and censorship of one of the most brutal police states of recent history, many East German musicians were able to produce music that still sounds good today, and there remains a whole world of East German pop and rock music that is largely forgotten and not listened to. So consider this your guide to Der Hits die DDR, as we explore the soundtrack to a country that no longer exists.

To help us navigate through the vast back catalogue of East German music, we’ve teamed up with John Paul Kleiner, creator of the GDR Objectified blog, and regular contributor to Radio GDR, an English language podcast on the life and times of East Germany. “I’d have to say that my favourite artist is Pankow,” explains Kleiner, “A band that emerged in East Berlin in the early 80s and whose lyrics really managed to capture the frustrations facing many GDR young people. They were a rock ‘n roll band clearly influenced by Western bands, but here too they came up with an original take on the source material. Great stuff.”

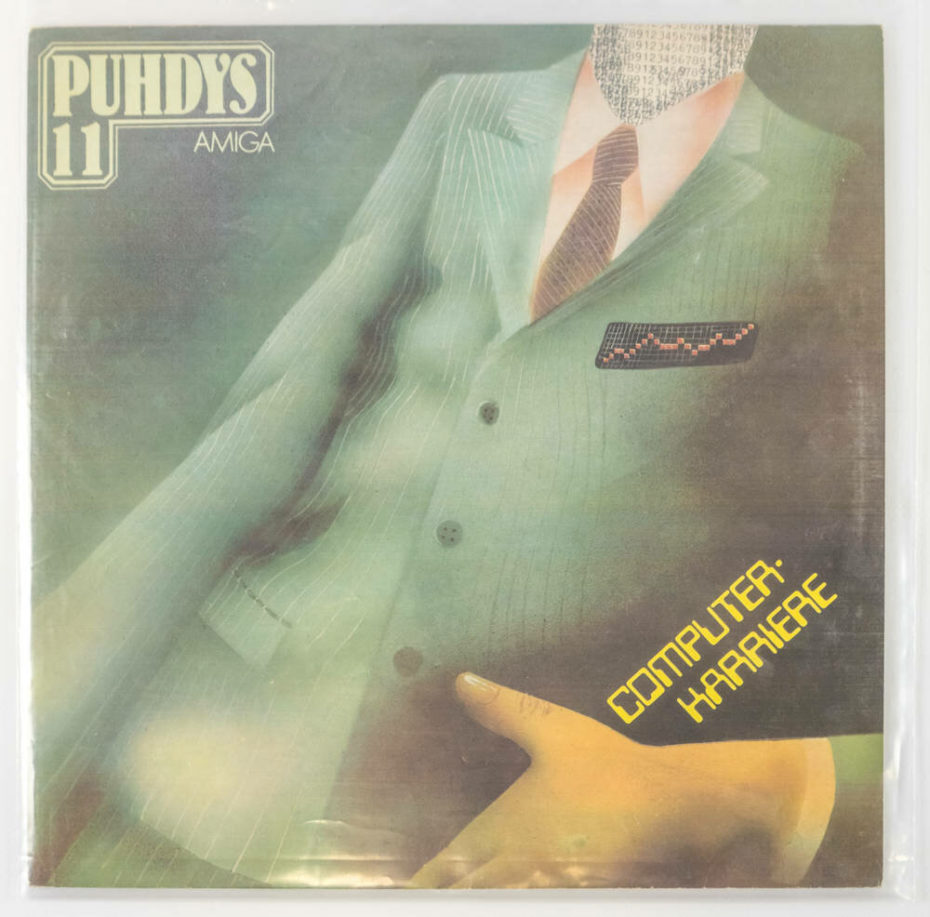

THE PUHDYS

Our first stop in the forgotten East German hit parade is one of the great successes of the GDR music scene, the Puhdys. Formed in Oranienberg in 1969 and still around today, the Puhdys were able to tread the fine line between staying within the strict government controls whilst remaining genuinely popular. The Puhdys were so well regarded in the GDR and beyond, they were the first band allowed to tour the West.

Making rock music in the GDR was hard. Whilst many bands in the West got their start by simply picking up instruments and playing in their garages and local school dances, bands in the GDR enjoyed no such freedom. “Accessing rehearsal space was hard,” explains Kleiner. “It was limited and overseen by Party loyalists to ensure the young people were developing into healthy ‘socialist personalities’. ‘Unmonitored practice space’ was virtually non-existent; some musicians (especially punks) set up shop in abandoned apartments rigging up their own electricity, but they were the exception.

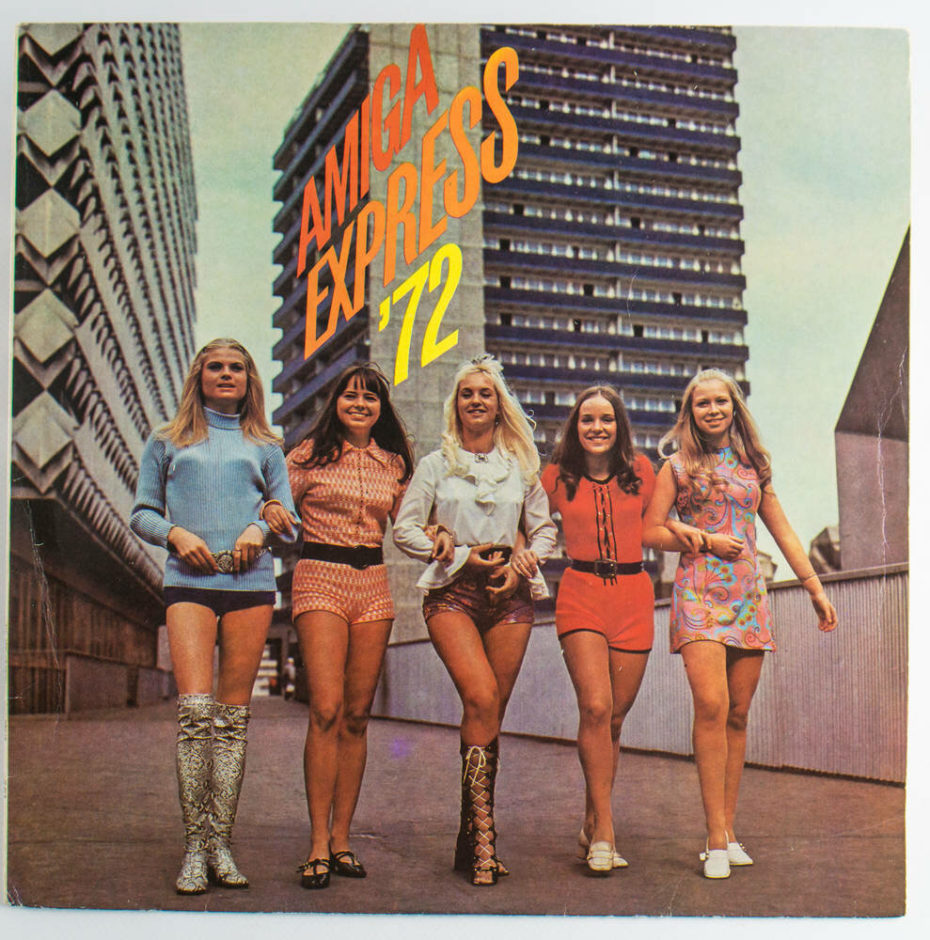

Declaring that “groups must remain political instruments of our Youth Organisation”, the ruling East German Party, the SED, began implementing draconian rules for musicians. To begin with, there was only one record label in East Germany, the State owned Amiga Records, and one of their best selling artists were the Puhdys. A group of young people couldn’t just start a band, write some songs and then book a show at a local pub. The hurdles in the way were considerable.” But despite these severe restrictions, the Puhdys made some of the most enjoyable music of the GDR.

To prevent an East German band recording the equivalent of the Rolling Stones’ “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction”, all lyrics had to be submitted to the government to check for possible subversive content. Playing a gig was also complicated. As Kleiner explains, “if you wanted to appear in public you needed to audition for representatives of the Ministry of Culture and demonstrate your musical abilities.” If you passed, your band could get the all important license to perform, the Auftrittserserlaubnis.

“Formally, all bands had to adhere to these rules,” says John Paul Kleiner. “Every venue was regulated by the authorities; aside from rare shows under the auspices of a church (Lutheran or Catholic), public performances happened in places where the Party set the rules and it was in the interests of the promoter or manager of the youth club, not to let their venues be ‘misused’. Some of these people were more courageous than others, but those in charge bore responsibility for what happened on the stages they oversaw and if there was a problem, they would experience repercussions. It was common practice for cover bands to submit set-lists before shows. In many cases, however, the set-lists submitted didn’t necessarily reflect what was played on stage. At the shows, things could go badly if the band didn’t adhere to the rules and if the wrong person was in the audience or the audience got out of control in a way that drew attention to the performer. It was a tight-rope walk if what you were doing was in any way unconventional.

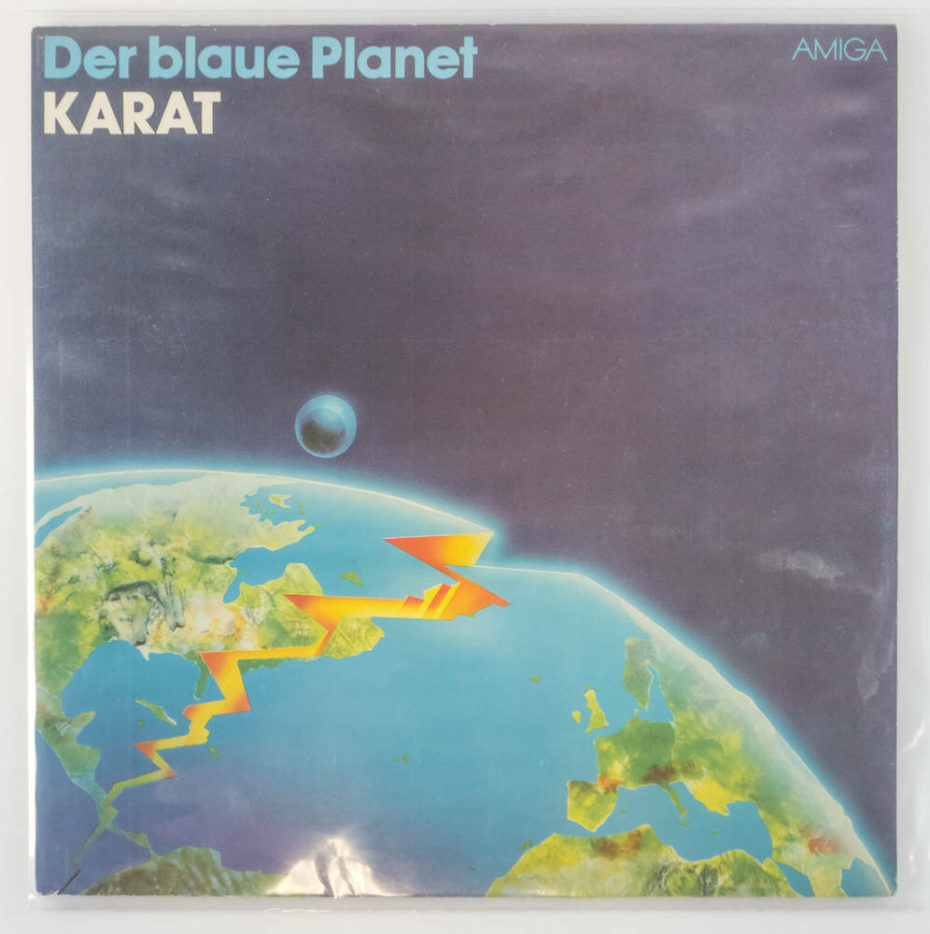

KARAT

Next up is one of our personal favourite Ostrock bands, Karat. Another of the Amiga Records’ great successes, prog rock Karat were formed in East Berlin, 1975, and are also still around today. Adept at sneaking in lyrics which challenged the GDR’s strict travel restrictions, such as the epic song Albatros, (“der Albatros kennt keine Grenzen… the albatross knows no borders”). Part of the charm in exploring GDR music is in discovering bands that sound like well known Western groups, but were working in a parallel, closed off universe. If you were an East German teenager into rock music, it might have been next to impossible to get hold of a copy of ‘Exile on Main Street’ for example but there was Karat’s 1982 masterpiece ‘Der blaue Planet’.

Like Puhdys, Karat were also allowed to cross over to play in the West, albeit with highly strict measures in place to prevent defecting. “Any band allowed to travel West was in a privileged position in the East and they knew it,” explains Kleiner. “As with any defectors, there was the ever-present threat of retribution on their family members left behind the Iron Curtain; that was a very real threat and kept most people from seriously entertaining the idea of staying on in the West. It was normal for GDR bands to have an entourage accompany them on trips West and someone in that group would most certainly have had ties with the Stasi and Cultural Authorities. Tabs were absolutely kept on band members, what they got up to and who they met with. Those controls loosened somewhat in the late stages, but never completely.”

KLAUS RENFT COMBO

Whilst bands like Karat and Puhdys thrived in the GDR system, other groups fared less well.

Klaus Renft, formed in Leipzig in 1958, quickly gathered a large following with his British-Invasion inspired rock and roll. Banned in 1962, Klaus Renft renamed his band the Butlers. But a riot at a Rolling Stones concert in West Berlin in 1965 was enough for the East German government to issue a blanket ban on all ‘Beat’ groups including the Butlers. In Leipzig, October, 1965, where fifty four groups had been banned, over 2,000 teenagers took the streets in protest. The so-called ‘Beat Riots’ saw violent clashes, 267 arrests, 97 of whom, as Kleiner explains, “were forced to work in open-pit coal mines just outside of the city even before their cases had gone to trial.” Resurfacing in 1967 as the Klaus Renft Combo, and sounding a bit like the GDR version of Led Zeppelin with a dash of Pink Floyd, Klaus Renft became one of Amiga record’s best selling acts between 1970 and 1975. Kleiner explains, “In addition to the band’s high-intensity live show, fans were attracted by the group’s willingness to address taboo subject matter that reflected the reality of everyday life for many in the ‘Workers and Peasants State’. While this approach brought them a large and loyal fanbase, it also meant constant friction with Cultural Authorities and SED leaders.” But the band’s huge success and popularity was extinguished overnight when they were banned in 1975…

Deemed “too radical” by the Stasi, the long-haired, bearded group members were summoned on September 22nd, 1975 to the Ministry of Culture to perform and try to get their Auftrittserserlaubnis renewed. On arrival however the popular band were told by the committee that “we are here to inform you today, that you don’t exist anymore”. The band were informed that their lyrics “had absolutely nothing to do with Socialist reality. The working class is insulted and the State and Defence Organisations defamed.” Not only were the Klaus Renft Combo banned from playing in public anymore, but the entire Amiga back catalogue was reprinted without any trace of the band’s recordings and achievements. As Klaus Renft told Anna Funder in her 2004 book, Stasiland, “We simply did not exist anymore. Just like Orwell.” Reunited after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the seminal band are still touring today, their website proudly proclaiming Legenden Sterben Nie: (Legends Never Die)

THE LIPSI DANCE

One of the more peculiar chapters in GDR music history was the Lipsi Dance. Appalled by the ‘decadent and provocative’ hip gyrating performances of Elvis Presley, and the ‘indecent’ spectacle of Western teenagers dancing too closely together in dances like the Twist (which was swiftly banned), Party leader Walter Ulbricht requested a home grown dance move and song be created – one that would be far more wholesome, and politically correct for the Socialist party. The result was the slightly bleak-sounding Lipsi, created in Leipzig in 1959 by composer René Dubianski, and a dance couple Christa and Helmut Seifert.

The government controlled all aspects of the Lipsi’s creation, and had high hopes of creating a teenage craze embodying “a legitimate expression of the joy of life”, but the Lipsi turned out to be hugely unpopular. David Byrne described the project as, “a weird sexless popular dance, that the government attempted to insert into popular culture.” Very few teenagers took to ‘doing the Lipsi’. “It wasn’t a hit with dancers,” explains Kleiner, “and after pushing it in a big way for a number of months, the Party finally gave up.”

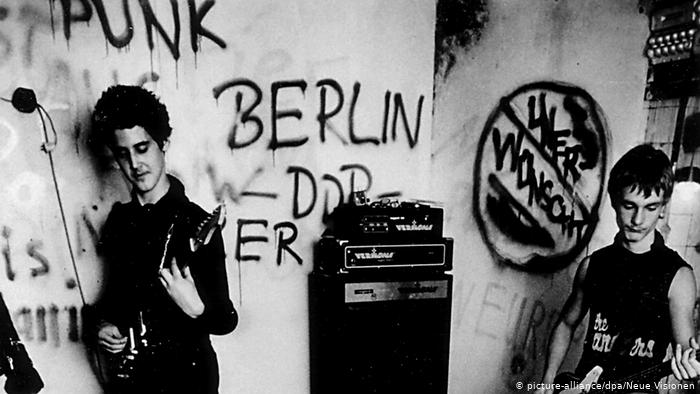

PUNK

In 1971, Erich Honecker, the co-founder of the Free German Youth (FDJ) organisation, became leader of the GDR, promising a programme of ‘consumer socialism’ and a more relaxed attitude to music. Amiga even began releasing certain Western records, mostly by artists who were seen to stand up for the working class in the West, such as Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen. As Kleiner explains, “those albums were available in the shops, well, in theory, but the popular ‘approved’ titles were in short supply. But there were certainly Party members, apparatchiks and authority figures who would have frowned upon that music and made that known.” The FDJ would even begin to invite certain Western artists to perform behind the Wall, and in 1973 there was even a GDR version of Woodstock, the World Festival of Youth and Students, that featured world music from left leaning countries like Cuba, Chile and African Solidarity.

But whilst some Western music began to be somewhat acceptable to the GDR government, punk was positively persecuted. Needless to say, the Stasi paranoid about the anarchic potential and appeal of punk bands amongst dissatisfied East German young people. But in an interesting contrast to punks in the UK, who in the early summer of 1977 were rallying around the Sex Pistol’s message of ‘No Future For You’ in ‘God Save the Queen’, East German punks rebelled against what Tim Mohr, in his fascinating book ‘Burning Down the Haus’ describes as “too much future.” For life as an East German youth was strictly and somewhat depressingly laid out. Membership and socialist indoctrination in the FDJ was virtually enforced. Students generally left school at 16, when they began to be “integrated into the planned economy through an apprenticeship in a specific field of work.” Whilst at school, students would even work several hours a week in factories, as part of a curriculum called Produktionsarbeit. Teenagers were funnelled into the workplace or the military, with unemployment, quite astonishingly, being declared illegal.

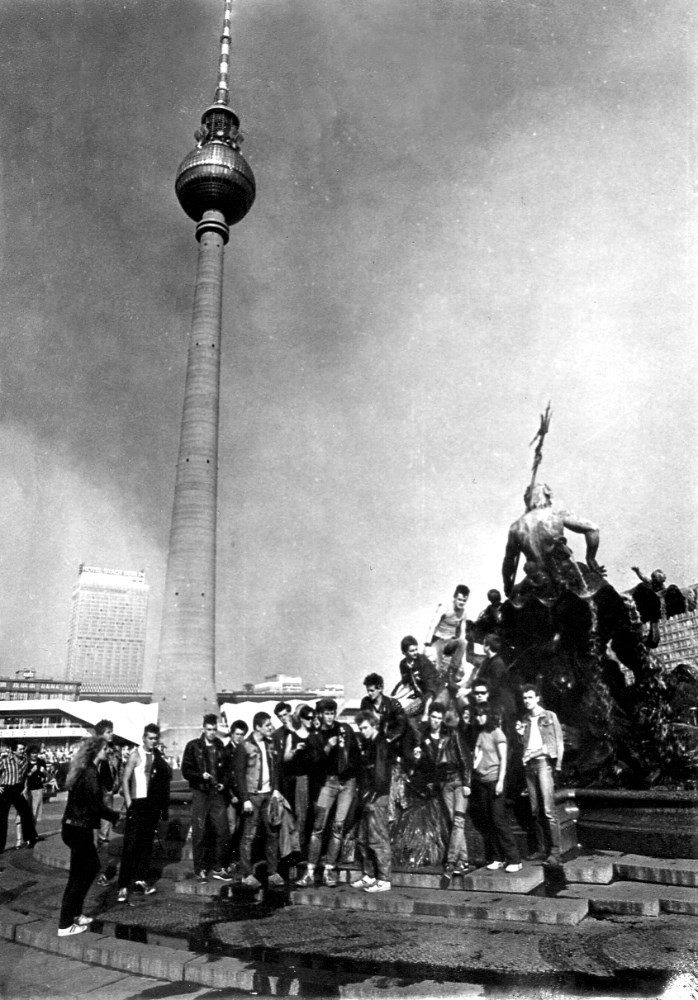

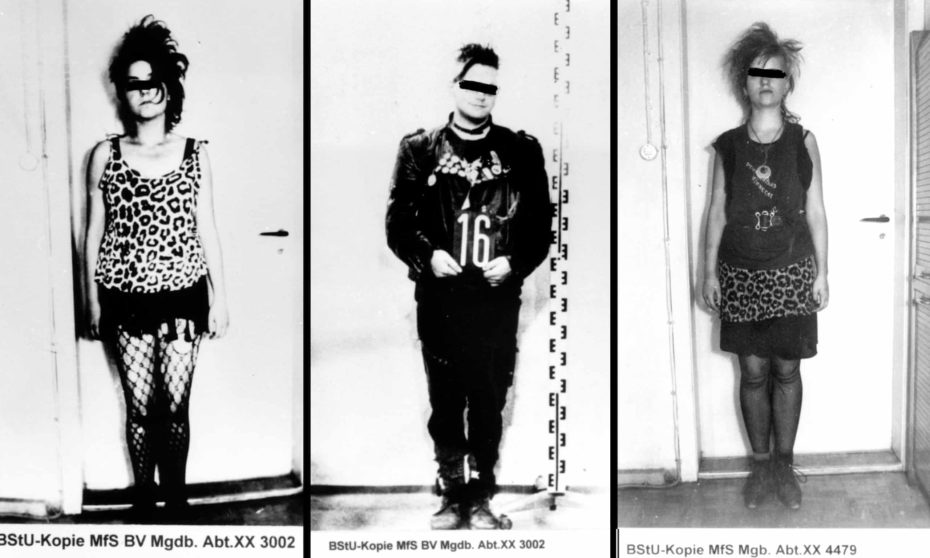

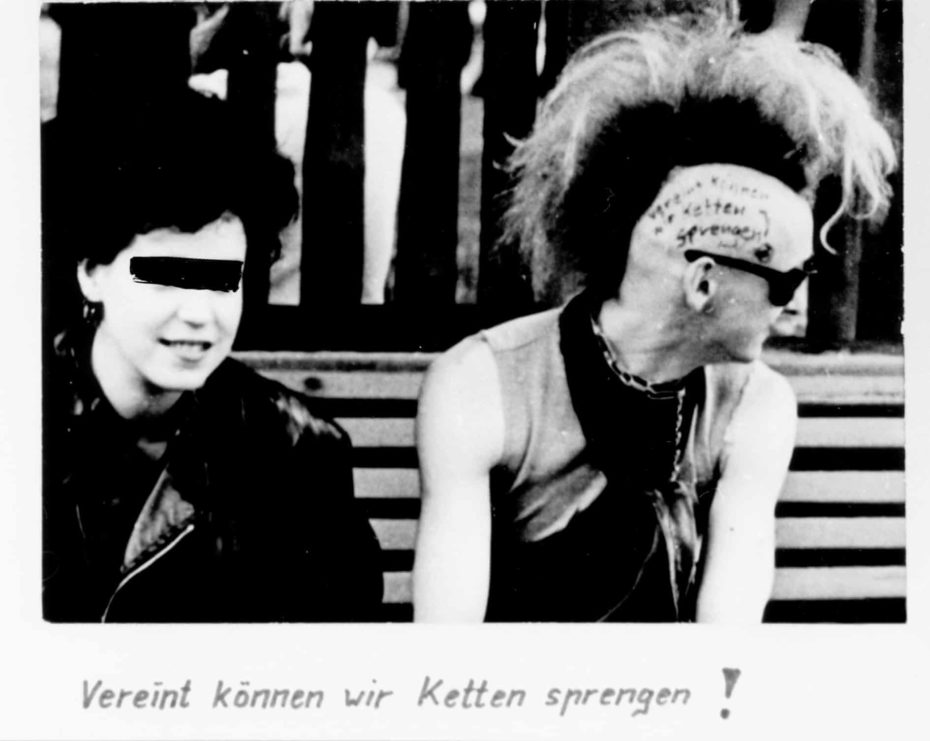

Rebelling against this system, East German punks began adopting the startling visual look of British punks, sporting ripped leather clothes adorned with safety pins, buttons with anti-dictatorship messages such as Strib nicht im Warteraum der Zukunft ‘don’t die in the waiting room of the future’ and spiked mohican haircuts. The Stasi swiftly marked down punks as the ‘leading force behind anti-government activity’, and punks gathering in public places like Alexanderplatz in East Berlin were routinely picked up for 48 hour interrogations. By 1983, the Stasi issued a blanket ban on punks meeting in public places, bars and cafes. As Tim Mohr reports, “they made it clear that any establishment caught ignoring the ban stood to lose its license.” Surveillance and police harassment was replaced with prison sentences and beatings, as punks were blacklisted from jobs, and as not having a job was illegal, they could be imprisoned again in a vicious cycle.

The Stasi even infiltrated leading punk bands like Wutanfall and had band members working as informants. Mohr describes the treatment dished out to their frontman, Chaos, who, “was savagely beaten and kicked. He’d been hit and punched at police stations before, but nothing like this. When it was over, he was covered in hematomas, splattered with blood. They took him, trembling and battered, into the Stasi station house and made him sign a statement attesting that he had been treated well during his detainment. They had to move his hand for him as he signed.” Punk band L’Attentat were formed out of the break up of Wutanfall, only for their lead singer Bernd Stracke to end up in prison after his guitarist leaked information on him to the Stasi. Despite all this harassment, a thriving underground punk scene still flourished with impromptu gigs held in basements and churches, and illegal cassette recordings swapped hand to hand.

POP MUSIC

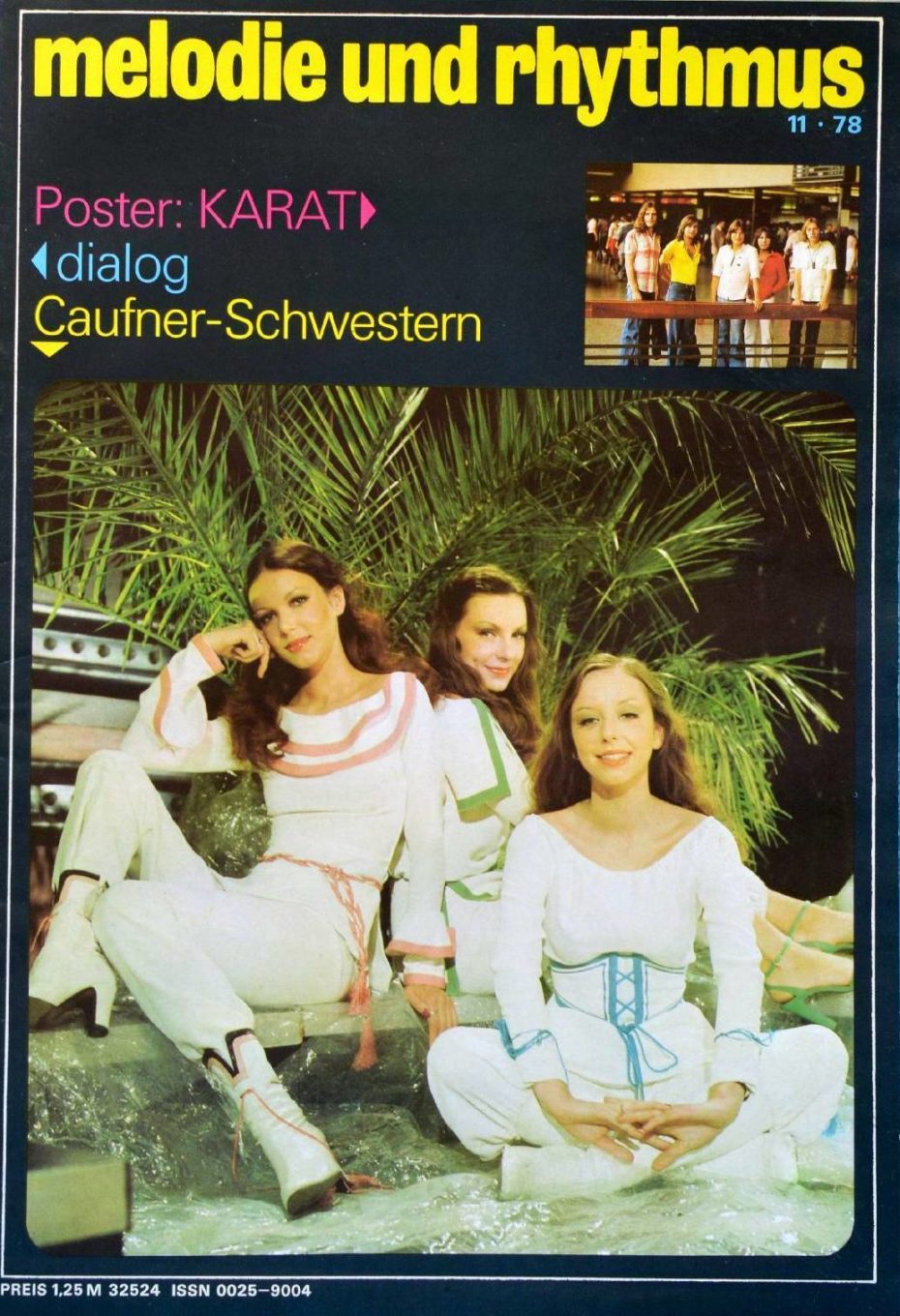

For the more mainstream young East Germans, the GDR government tried to create an engaging pop scene similar to its Western counterpart, with music magazines like ‘Melodie und Rhythmus’, and variety TV shows like Ein Kessel Buntes, Bang Stop!, Beatkiste, Tip-Parade, and Tip-Disko. Amiga records never made the transition to CDs, but there were even music videos that wouldn’t have looked out of place on MTV in the mid 80s.

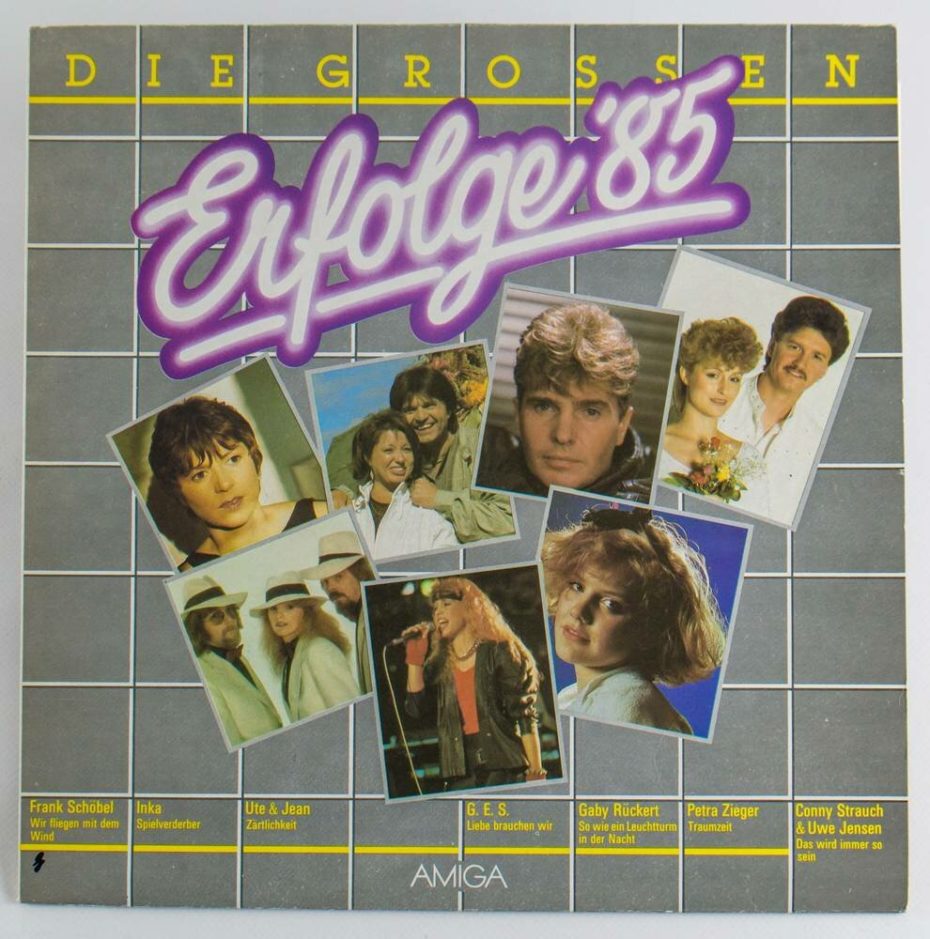

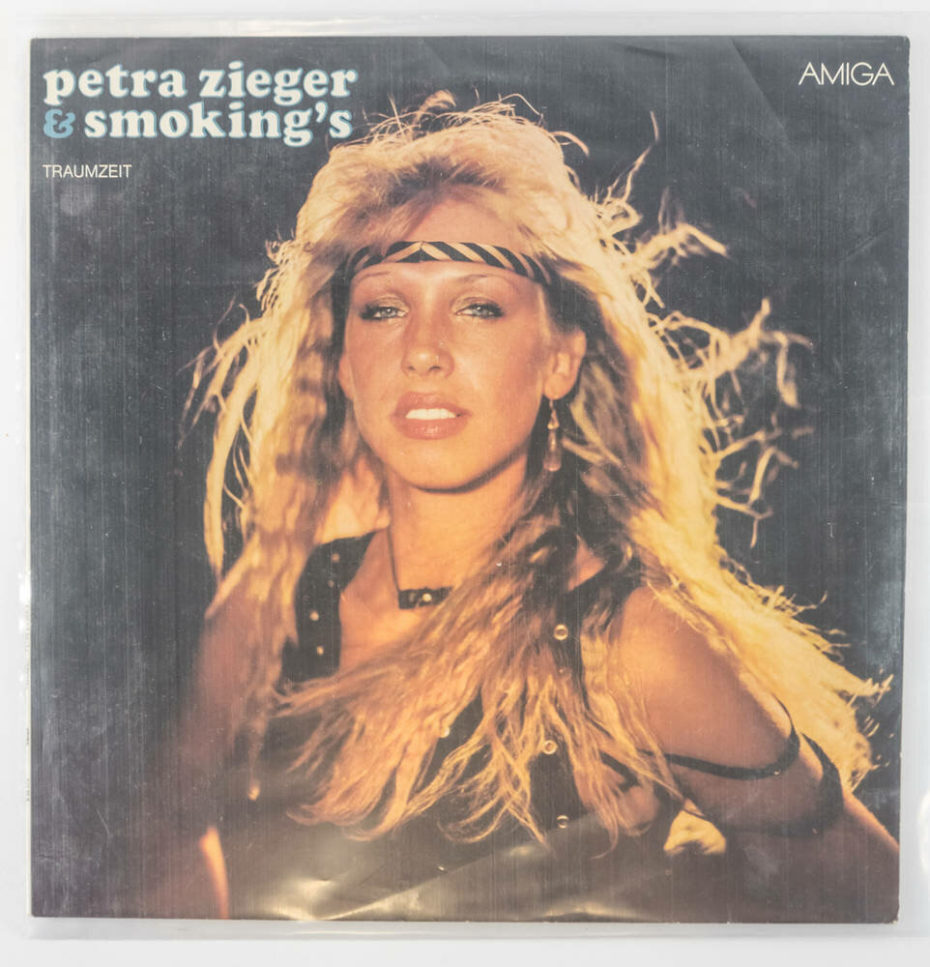

As Kleiner explains, “There was an effort to produce something similar to what Western shows were doing”, but the government aimed to keep a tight lid on the media. They mandated a 60/40 clause, which stated that 60% of all music broadcast or performed had to come from the GDR or other Eastern Bloc nations. At one point Amiga Records had around four hundred artists on its books. Bands like City, founded in East Berlin in 1972, offered a guitar driven sound and a front man with a moustache to rival Freddie Mercury. There was Petra Zieger, the first lady of East German pop; whilst solo singers like Ines Paulke and Wolfgang Ziegler produced 80s power pop.

If you had trouble tracking down LPs by Johnny Cash, East Germans could enjoy the deep bass country singing of Peter Tschernig…

But no matter how hard the SED tried to create what John Paul Kleiner describes as “a socialist youth culture from the top down”, the level of interest could never be compared to that of popular Western music. “There was a genuine effort to present a socialist culture which was truly international in its influences and varied in its styles,” says Kleiner. “There were media platforms for these various musics and funds to train and foster artists. It didn’t work though and ultimately the Party gave up trying by late 70s and early 80s, because GDR youth simply weren’t interested and so these transmissions belts of socialist culture were not serving any real purpose.”

Efforts to appease East German youth saw the FDJ put on concerts by the likes of Billy Bragg and Bruce Springsteen, who played to nearly 300,000 people at East Berlin’s Weissensee Cycling Track in 1988. But these concerts backfired, simply highlighting what East Germans were missing out on. Before playing Bob Dylan’s Chimes of Freedom, Springsteen spoke in halting German: ”I’m not here for any government. I’ve come to play rock’n’roll for you in the hope that one day all the barriers will be torn down.” The electric atmosphere was described by one fan as a “moment some of us had been waiting a lifetime to hear”.

In the same year, popular West German singer Rio Reiser was allowed to play in East Berlin, with the most moving moment in his show being a solo rendition of ‘Der Traum its aus’ (The Dream is Over). The chorus went…

“Is there one country on this earth

Where the dream is reality?

I really don’t know

But one thing I know for sure

This country isn’t it”

Interestingly, the show was recorded and broadcast on DT64, the youth station, but that song was left on the cutting room floor.” The next year, the Berlin Wall fell, and after reunification, Western interest in the old East German bands was virtually nil. Today, outside of a relatively small audience, knowledge of these bands and the struggles they went through to produce music amidst a brutal state controlled dictatorship is all but forgotten.

Our final song is by GDR prog rock favourites Karat, and 1979’s poignant Über sieben Brücken (Across Seven Bridges). “I love the song’s melody,” says Kleiner. “But it’s the lyrics which have made it one of the most popular and important songs of the GDR era. It captures the very real sense of division, longing and hope that many East Germans felt in the 80s. That song was written for a TV movie with the same title; both are based on a short story about an ill-fated relationship between an East German woman and Polish man which was written by a writer friend of the band. While the song was inspired by the relationship at the centre of the story, the lyrics take on a sort of universal meaning through the chorus (Über sieben Brücken musst du gehen” / You must cross over seven bridges . . .) which deals with the need to keep hope during the trials one is dealt by life. The song was covered by a West German artist (Peter Maffay) very shortly after its release in the East and was a huge hit on both sides of the Wall. Some call it the ‘unofficial’ GDR national anthem.