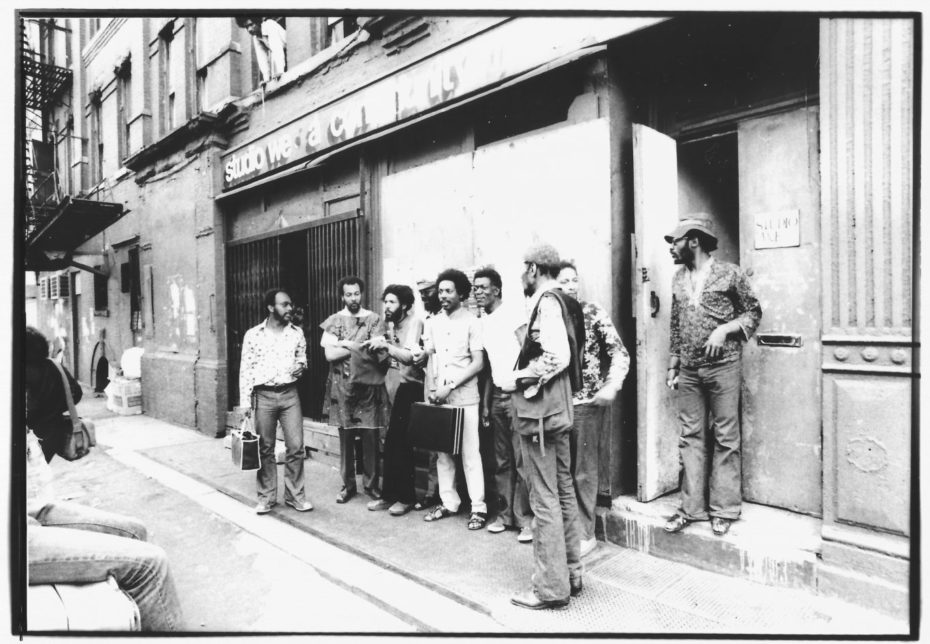

Once upon a time, before Manhattan priced out its young talent, you had to be an artist to live in SoHo. And in the late 1960s and 70s, a cultural phenomenon known as “Loft Jazz” came into existence in downtown Manhattan’s abandoned industrial spaces. Eclectic, edgy and often Black musicians turned Soho’s neglected lofts into places where they both lived, rehearsed, recorded and performed. Before gentrification hit, musicians fled small town America to squat these urban spaces vacated by the manufacturing industry, storing their clothing in filing cabinets and using the fire escape to come and go. They were there out of necessity, but also to flourish. “To those who remembered them fondly”, says Michael Heller in his book Loft Jazz: Improvising New York in the 1970s, Soho’s squats “teemed with artistic opportunity. Where music could be experienced every night on every block, and opening a venue could be as simple as opening your living room.”

John Coltrane’s drummer Rashied Ali converted his apartment on 77 Greene Street into what was referred to as Ali’s Alley, and founded his label Survival Records there. He built a bar, a bandstand and even served food out of the loft. There would still be a line in the street at 1am for the last set. Although the Alley closed in 1979, its legacy continues in the New York jazz scene today. Rashid Ali explained to the New York Times that jazz lofts “started as places to rehearse and jam. Then like in the 20’s, they turned into ‘rent parties.’ Back in the 60’s, you could get a loft for next to nothing — just to watch the building for a cat who didn’t want to brush the bums off his doorstep. At first, you had to know a musician to get into the loft; then, little by little, the musicians started charging a dollar, dollar fifty, entrance fee.”

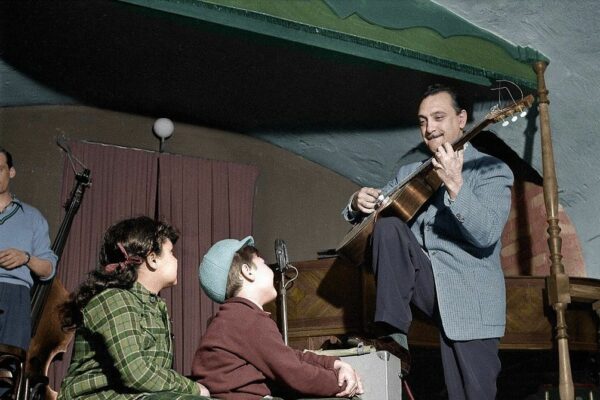

The converted factories and warehouses allowed music to be free of the constraints that might be present in the smaller nightclubs and venues of Harlem, trending towards more experimental and avant-garde jazz. Each Jazz Loft had its own ambience, just like any venue. Writer Michael Heller defines them by a number of key characteristics, including ” (1) low admission charges or suggested donations, (2) casual atmospheres that blurred the distinction between performer and audience, (3) ownership/administration by musicians, and (4) mixed-use spaces that combined both private living areas and public presentation space.”

The Alley was buoyant, communal, and serious, and most folks said it was the best. Studio We, run by trumpeter James DuBois and bassist Juma Sultan, was one of the earliest jazz lofts, at 193 Eldridge Street. In the late 1970s, it was written that “the studio stands apart from the gutted buildings, broken sidewalks and manic sadness of the neighbourhood. Its building is brightly painted. The first floor, which used to he a small cabaret, is now being converted into a jazz club. There is a large bandstand to the right of the entrance; the rest of the space is filled with tables, benches and a bar.”

Composer and musician, Sam Rivers transformed his loft a few blocks over on Bond Street, and he named it Studio Rivbea. At the time, it was “the first in a series of small converted performance spaces that would comprise what’s now considered NYC’s loft jazz scene.” A series of recordings made at Studio Rivbea during the 1976 Jazz festival were released under the title Wildflowers on the Douglas label.

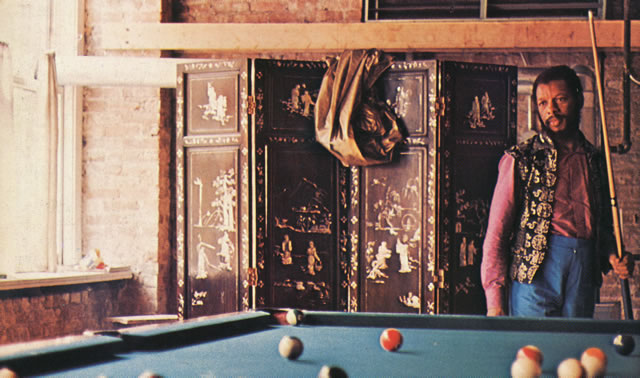

Ornette Coleman spent six years in his Jazz Loft at 131 Prince Street, which he came to call “Artist House”. Rehearsals and all-night jam sessions were held on the first floor in a space of about 3500 square feet. It became more of a public venue in 1970 when he and his cousin Jordan cleaned and renovated the downstairs loft, and then booked a regular calendar of events. It stayed very intimate, never serving alcohol but serving as an art gallery in tandem to the concert venue. Not all Jazz Lofts were on a path to becoming formal institutions, in fact, some of them directly opposed the venue model. “You must watch the term ‘loft jazz’ because it’s too limiting. We didn’t come to New York to play in lofts; we came to make a living,” said pianist Muhal Richard Abram. “But an audience can start, and grow until it gets too big for lofts and the music moves to another level. That’s what we’re interested in. That’s what we’re building towards. We will make it. There is no doubt about that”.

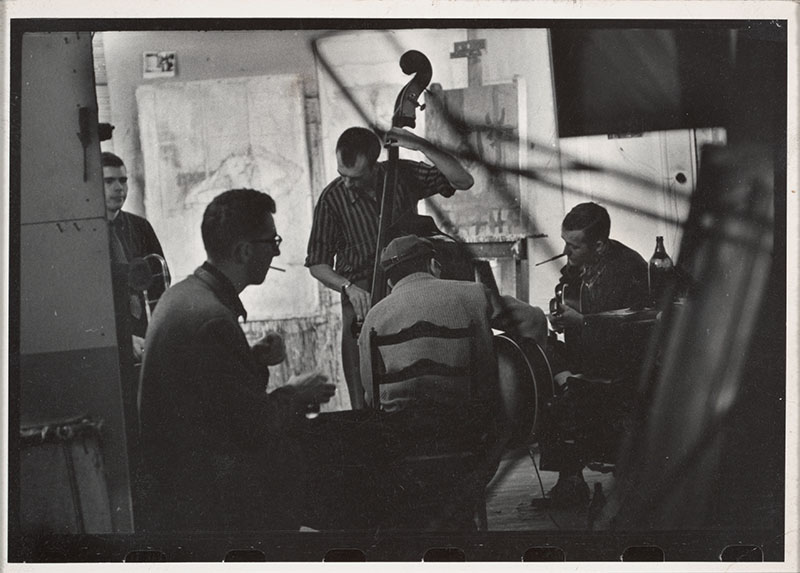

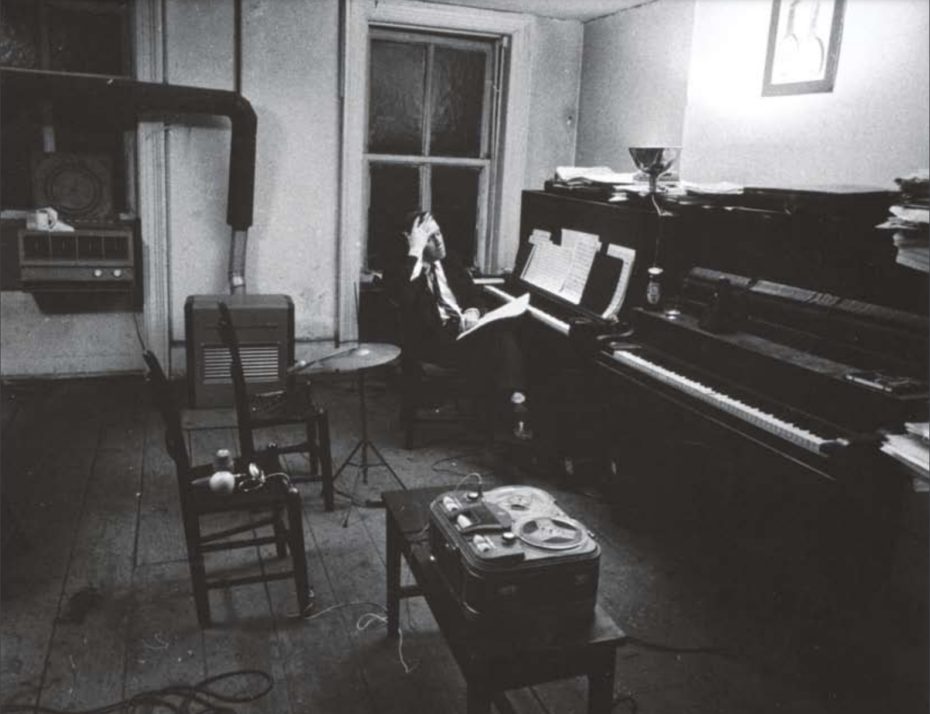

The loft scene began to decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s, mainly due to a steady rise in rents. Studio Rivbea, which was first owned by Robert DeNiro’s mother, a painter, is today a theater while Number 77 Greene Street, formerly Ali’s Alley is now a clothing store with renovated loft apartments above it. After a new wave of gentrification swept through Lower Manhattan in the mid-2000s, most notable jazz lofts have since become big brand retailers, banks, and luxury apartments. Though their footprint might have been dusted over, photojournalist W. Eugene Smith recognised the Jazz Lofts as something truly special and worth documenting. He lived in a Midtown Jazz loft and immersed himself in the scene, taking over 40,000 photographs and 4,000 hours of audio recordings; jam sessions, conversations between musicians, the building’s ambiance, telephone calls and more. A 2015 documentary highlights Eugene’s work in the jazz lofts:

Since Manhattan’s elite skipped town in the wake of the pandemic, just think of all the sweet jazz that could be made again in those newly abandoned luxury lofts!