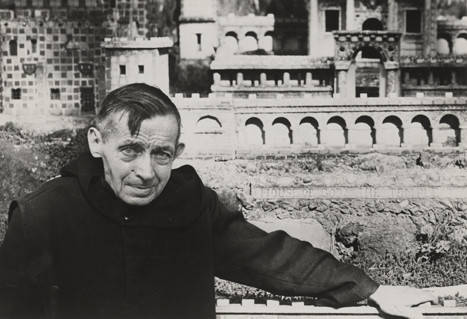

Death seemed to stalk Michael Zoettl from birth. His mother died when he was a child. He nearly drowned, then almost burned to death. When the Asiatic flu pandemic swept through Europe in 1889, killing 1.5 million worldwide, Michael fell ill and developed permanent heart palpitations. Zoettl was 14 years old when, in 1891, the German Benedictine monks of St. Bernard’s Abbey in Cullman, Alabama, arrived in his Bavarian hometown of Landshut to recruit students for their newly established monastery and school. The following year Zoettl – soon to become Brother Joseph – crossed the Atlantic on the Suavia and entered the United States through Ellis Island. That journey was the last time he would see much of the world beyond the monastery grounds. But soon he would bring the world, in miniature, to the tiny town of Cullman and to thousands of pilgrims and curiosity seekers.

A small town in the deep South, less than 30 years removed from the Emancipation Proclamation that ended the enslavement of Black people in the United States, hardly seems the kind of place you’d find a German Catholic monastery. But a wave of German immigrants to the U.S. in the mid-1800s attracted a group of monks to establish a Benedictine presence to serve the German-speaking population. Zoettl was a small man, standing less than 5 feet tall, and was unusually quiet and withdrawn, even by monastic standards. But he was not afraid of hard work. He threw himself into his studies, learning English and intending to become a priest until another brush with death ended that ambition. While working on construction of the abbey’s belfry, Zoettl was injured when a heavy bell fell and crushed him. The accident exacerbated an existing condition and left him with a hunched back.

While Zoettl recovered, his superiors debated what to do with him. At the time, a physical disability was considered a “canonical impediment” to the priesthood because it would be “distracting” to parishioners. So Zoettl was permanently shut out of the role. Yet somehow his disability didn’t seem to disqualify him from physical labor. He worked as the housekeeper for the abbey priests for several years before being assigned to maintain the abbey’s coal-fired power plant. The work was long, tedious and physically exhausting; his days frequently stretching into 17 hours of shoveling coal and watching gauges. Eager for a way to pass the time, Zoettl built two miniature grottos to house small statuettes of the Virgin Mary a fellow brother had received in a shipment of 500. When the first two sold quickly in the monastery’s store, Zoettl built grottos for the remaining statues as well. His creative impulses stoked, he kept building, constructing 5,000 grottos before he stopped counting.

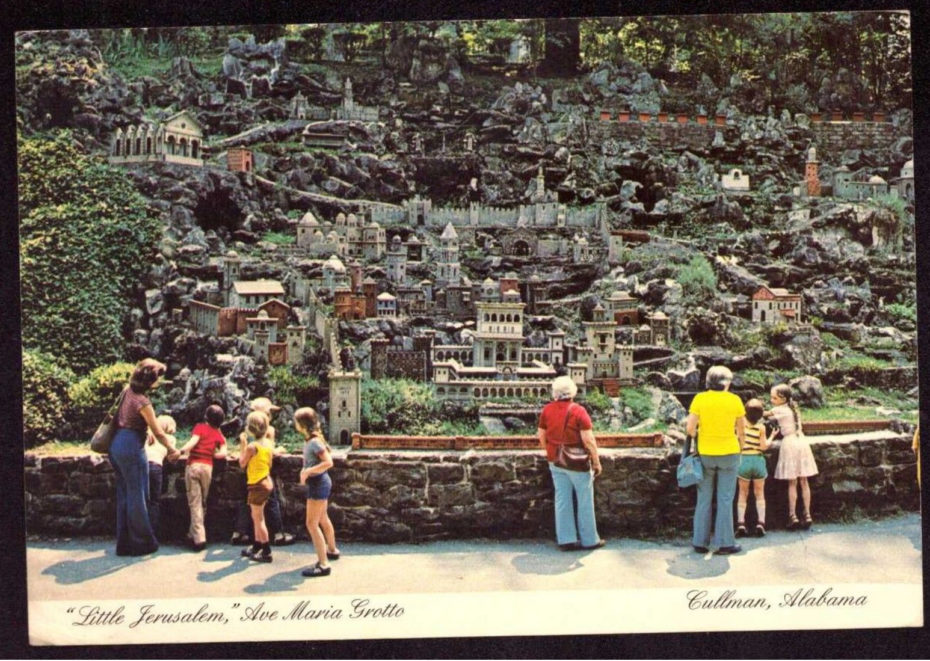

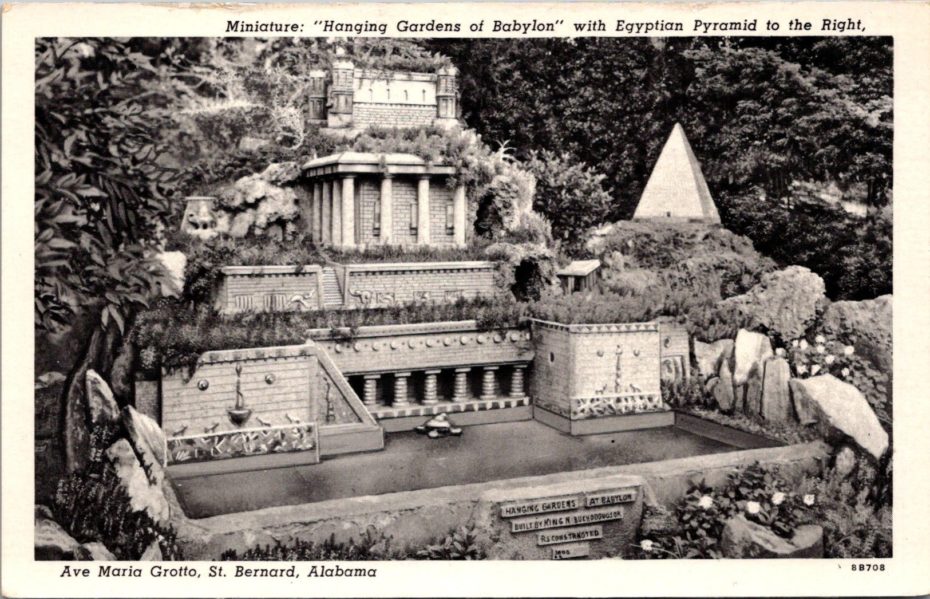

Using simple hand tools and found objects – bits of broken pottery, shells, leftover tiles, marbles, chicken wire – he branched out from tiny grottos into a model of the city of Jerusalem, which he installed in the monastery’s garden in 1912. Originally meant just for the resident monks, Little Jerusalem soon attracted curious tourists. In fact, so many visitors arrived that the abbot told Zoettl he had to quit his little hobby because it was disturbing the monastery’s operations. Zoettl asked permission to move his creation to an old quarry on the grounds but was denied.

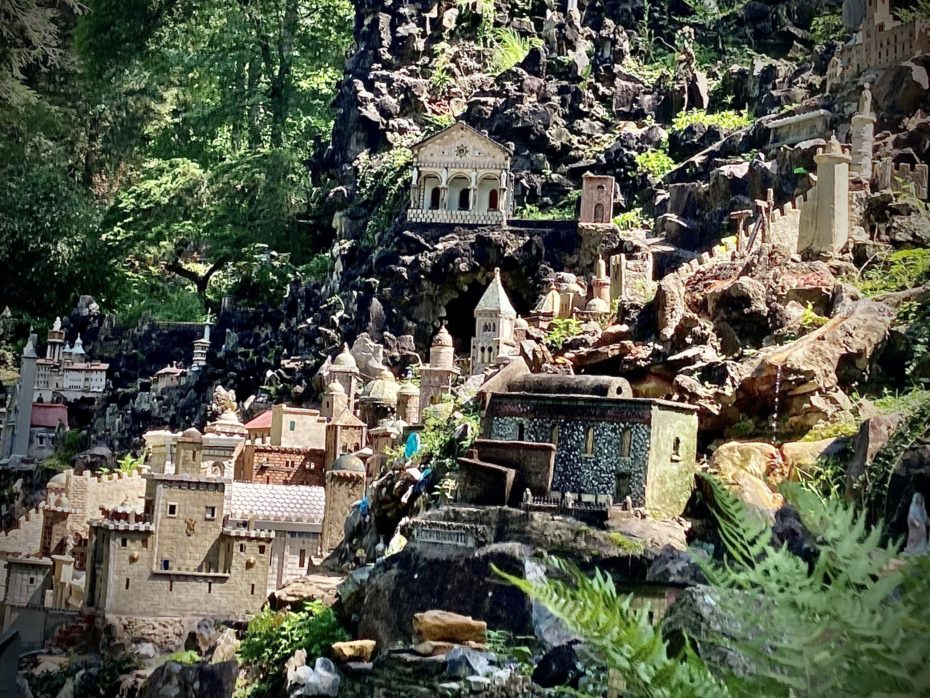

A few years later, cooler heads (and perhaps the siren song of easy revenue) prevailed, and in 1932 Zoettl was given four acres of former quarry land to fill with miniatures for public display. By then, years of wear and tear from accidents and hard labor had taken their toll. “I told Abbot Bernard I was getting old and could hardly do much any more,” Zoettl said. “But he would not listen. So I started work and had plenty to do.”

Then a literal trainwreck provided a little divine inspiration. A train carrying slabs of marble crashed near Cullman, rendering the cargo useless for building, at least for building at full scale. The broken pieces were gifted to Zoettl, and he embarked on the most ambitious piece of his installation, the Ave Maria Grotto, for which the whole site is named.

While many of Zoettl’s miniatures represent religious sites, the Temple at Jerusalem, the cave in Bethlehem where Jesus was born, St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and replicas of other churches and shrines around the world, the grotto is also suffused with an endearing sense of whimsy. “Hansel and Gretel Visit the Castle of the Fairies” depicts the brother-and-sister pair of Brothers Grimm fame exploring a jewel box of a palace, encrusted with sparkling beads, stones and trinkets. In a cave beneath lies a fierce red-eyed dragon named Restrained. The kind-hearted Zoetl placed a chain around the dragon’s neck to reassure children that the monster couldn’t harm them. The Tower of Thanks rises from the ground surrounded by cement and marble flowers sprouting on stems of rebar. The tower’s legs came from an old altar in the cathedral of Mobile, Alabama, and the green finials adorning the top are fishing floats sent to Zoettl from Ireland. The tower was dedicated to all the people who sent him materials and supported his work through the years. Even the historical monuments are a testament to Zoettl’s flourishing imagination. The only buildings depicted that he ever saw in real life were those of the St. Bernard Abbey and his hometown. The rest of the more than 150 pieces were created from postcards and the workings of Zoettl’s own mind.

His creations sparked wonder and curiosity, but Zoettl was famously shy and avoided interacting with the public. He worked alone during his long day shifts then placed his works in the grotto at night or early in the morning. If caught unexpectedly by visitors, he would pick up a rake and pretend to be the gardener to avoid questions and conversations.

The last miniature Zoettl created was a replica of the shrine at Lourdes, France, when he was 80 years old. Zoettl died three years later in 1961 and was buried in the abbey cemetery. After Zoettl’s death the abbey’s handyman Leo Schwaiger worked to preserve the site, even adding a few of his own creations in Zoettl’s signature style, among them the Great Wall of China, the Pyramids and a crosswalk for the local chipmunks who inhabit the grotto. Scwaiger died in 2016.

Art, like the people who make it, is never just one thing. The Ave Maria Grotto is folk art, an act of religious devotion, a roadside curiosity and a man’s simple hobby to pass the time all at once. Just as Joseph Zoettl was a survivor, an immigrant, a brother, an artist and a visionary.

The Ave Maria Grotto still welcomes visitors daily for a small fee.