The world’s greatest artists aren’t supposed to have their work overlooked or unattributed, but it happens more than you might think. In museums, private collections, and public spaces, there is a myriad of artworks that remain unidentified. It took years for a total of nine Van Gogh ‘fakes’ painted during the last four years of his life, to be authenticated by museums and ultimately emerge as the real thing. A Lucian Freud painting was once mistakenly placed in a disposal area of Sotheby’s warehouse and workers fed the case into a crushing machine. And in the Spanish Pyrenees, a beautifully odd building stood in decay for decades, because for a long time, nobody knew it was designed by genius Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi.

Though known and renowned in his own time, in his later years, Antoni Gaudi became an eccentric recluse. Consumed by his work at La Sagrada Familia, he holed up in a tiny room in the church’s crypt to better supervise the work. He lived there for 16 years until he was killed by a tram while crossing the street. Soon after his sudden death in 1926, he was largely dismissed by critics and forgotten. Ongoing projects were abandoned, finished ones left to fall to disrepair, and during the Spanish Civil War his Sagrada Familia workshop was even ransacked, leading to the destruction and loss of preparatory material that would be so valuable to scholars today. Gaudi was rediscovered by avant garde artists of the 1950s (principal among them was Salvador Dalí), leading in a resurgence in the architect’s popularity that culminated in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1957. Today Gaudi is duly recognized as the master of Catalan architecture and a leader of the modernist movement.

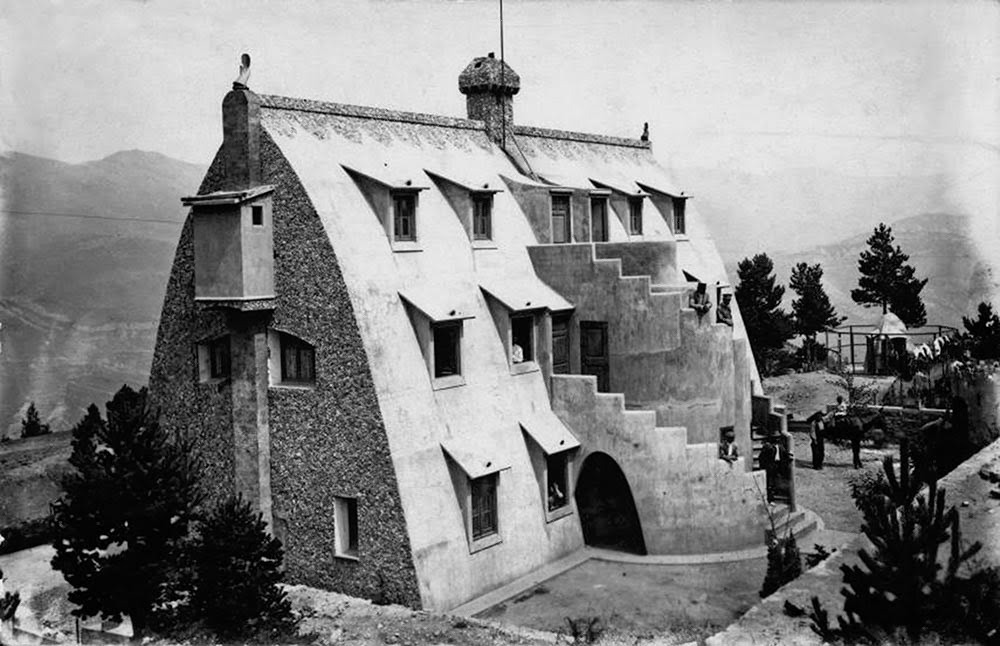

The Xalet del Catillaràs, also known as the Catllaràs pavilion, was designed and built between 1901 and 1905. The construction was paid for by Eusebi Güell, the wealthy Spanish industrialist and Gaudi’s primary patron. The chalet was designed to house employees of Güell’s coal mine and cement factory. It has a more spartan aesthetic than other Gaudi buildings, with a stripped down design and a notable lack of the architect’s signature art nouveau ornamentation, which probably contributed to the lack of attribution to the Catalan architect for so long. There was also the rise of Noucentisme, an architectural movement in the 1930s which was radically opposed to Catalan Art Nouveau and Gaudi’ Modernism. The instability of the Civil War and post-war period probably didn’t help either.

Although the first catalogue raisonné of Gaudí’s work did not include the pavilion, the first documented reference of the building can be found in an architectural magazine published in 1946. The recently discovered evidence refers to a conversation with Domènech Sugranyes Gras ( Gaudí’s collaborator in the Sagrada Família ) in which he assures the interviewer that Gaudi was the architect. Despite spending most of its existence unattributed and neglected, it is now accepted by officials that Gaudí is indeed the artist behind the pavilion.

In this isolated work, Gaudi paid homage to the mountain setting of the refuge (the town, La Pobla de Lillet, is in the Berguedà of county of Catalonia, with the Pyrenees nearby) in his choice of materials and style. The building consists of two long rooflines that give the chalet the striking shape of a pointed barrel vault, cleverly designed to keep snow off the roof. The other sides of the vault are lined with river stones. One side has a chimney, and along the three stories are windows with built in awnings. One of the most architecturally interesting elements of the refuge’s original design is the staircase, located on the south-western facade.

The chalet served the workers of Güell’s mine for several decades, until it was sold in 1932 to the city of La Pobla de Lillet. For a brief period of time in the 1930s the building served as the town hall. What followed was a period of gradual dilapidation, as the building fell to disuse. The chaos of the Spanish Civil War and post war period exacerbated the degradation.

The chalet was modified several times, first in 1907, then in 1940 and 1971 (when it was transformed into a summer camp). The roof was shingled over, the staircase replaced with one in metal, and the river stone sides were replaced with cement. After being used as a summer camp for several years, the chalet was abandoned in the 1980s.

After more than half a century of abandonment and degradation, finally, in the early 2000s, the Architectual Heritage Service began major renovations to the chalet’s original facade. The staircase was restored in 2016. Today visitors are welcome to tour the outside of the chalet, but the interior is closed due to ongoing renovations. What could be more idyllic than hiking through Spanish forests and coming upon a building designed by “God’s Architect”, the master who created the Sagrada Familia?

After completing the refuge, Gaudi undertook another project in La Pobla de Lillet. While working on the Xalet del Catillaràs, Gaudi was often hosted by a local businessman, Joan Artigas i Alart. To thank him for his hospitality Gaudi designed and constructed him a magnificent garden complex, the Artigas Gardens. The gardens feature a waterfall, arches, a cave, as well as multiple bridges and a viewpoint. The Artigas Gardens are full of whimsical ornamentation and Christian symbols, but like the Xalet del Catillaràs, the Artigas Gardens were abandoned and fell into disrepair around the 1970s. After a large-scale renovation that restored the site to it’s former splendor, it is now open to the public.

The Catalan architect who lived between 1852 and 1926i is known as the father of Catalan Modernism, a movement that emerged from Barcelona in the late 19th century. Gaudi’s style is contradictory and highly singular, drawing from sources as varied as the Gothic Revival, the natural world (many of his buildings utilize structures inspired by human skeletons), and the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution.

Born and raised in Reus, a town in Catalonia, Gaudi moved to Barcelona in the 1870s to study architecture. In 1878 he met Eusebi Güell at the World Fair in Paris, Güell would go on to become Gaudi’s most important patron, commissioning many of Gaudi’s most famous works in Barcelona, as well as the Xalet del Catillaràs. As a young man Gaudi was known as a vibrant, social member of Barcelona’s arts scene. Later in his life, however, the architect began to retreat into himself, becoming fervently religious and nearly hermetic. His major works include the Park Güell, Casa Mila, the Church of Colònia Güell and of course, the still unfinished Sagrada Familia.

Though the style of the Xalet del Catillaràs would hardly be held up as an example of the quintessential Gaudi aesthetic, the story of the building seems emblematic of the man himself. There is an unmistakable parallel between the forgotten lodge and Gaudi’s legacy as a forgotten architect. The rediscovery of the chalet therefore mirrors the way Gaudi’s reputation itself underwent a sort of renovation in the mid twentieth century, from neglect to appreciation.