The infamous nightclub singer and vaudevillian, Velma Kelly, opens the musical Chicago in a sleek bob haircut, slinky black dress and all the glamour and sin of the swinging 1920s. She’s going to “paint the town”, play fast and loose… and “rouge her knees and roll her stockings down”? The last line might seem nonsensical to the modern viewer, but painting knees really was “all that jazz” for flapper women embracing the freedom of shorter dresses and loser morals. And over the next decades, this curious trend evolved to elaborate knee art, a form of both creative expressive and women asserting agency over their bodies.

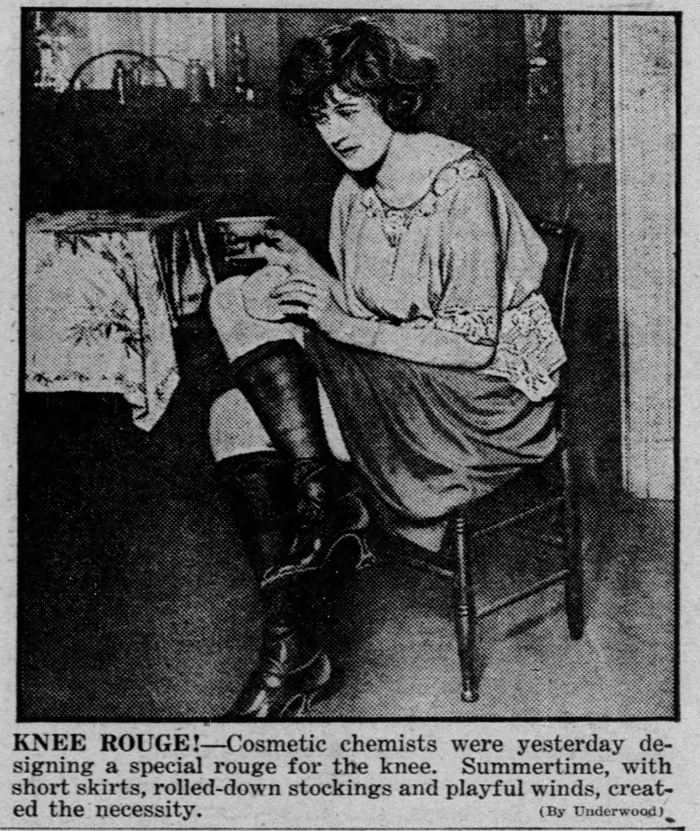

As Velma’s character croons, these young women often forwent garters and rolled their stocking down into a bunch, drawing attention to the knee. Dress styles were still too long to show upper legs, but the popular dances of the era, from the Charleston to the Fox Trot, allowed for glimpses of the blushing knees, bringing more attention to that illicit flash of skin. Flappers might have started rouging their bodies because the 1920s was also when cosmetic formulas were first developed for commercial use and many women copied the looks of movie stars, especially Theda Bara’s vamp aesthetic and Joan Crawford’s wide-eyed beauty. As Emily Spivack wrote in Smithsonian, blush had historically been associated with promiscuity, “but with the introduction of the compact case, rouge became transportable, socially acceptable and easy to apply. The red or sometimes orange makeup was applied in circles on the cheeks, as opposed to dabbed along the cheekbones as it is today.”

And while knees might not seem like the most, ahem, sexual body part, this trend represented women pushing taboos — and there is evidence that cosmetic companies even created a blush especially for knees. Still, they were met with pushback, especially when women began experimenting with full-on knee artwork: “It Kneed’t Be” was a popular headline. As Cynthia Grey wrote in her fashion advice column on the trend, “As women become more sophisticated in their tastes and become more elegant in their costuming, they abandon the freak styles.”

Or take a humorous poem published in the Dayton Daily News:

“Painted knees have hit the town,

Red and yellow, green and brown;

Goofy styles that give a pain,

Glimpsed ‘em down at Third and Main;

I like color on autumn trees,

But they look darn funny on a woman’s knees;”

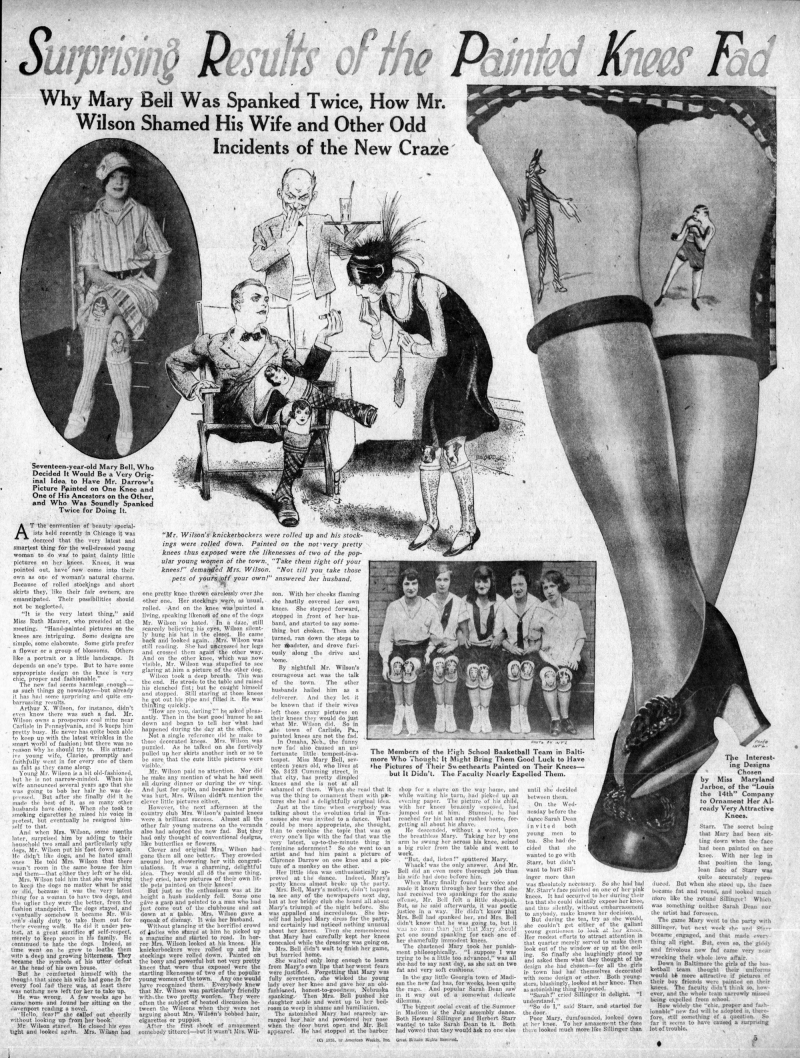

Still, this didn’t stop the artwork from becoming even more eye-catching: The Makeup Museum writes that beginning in the mid 1920s (and maybe even earlier in Paris), women used watercolors and oil paints for elaborate designs, an example of “creativity, provocation and rebellion.” Along with bobbed hair and thin eyebrows, they were all the rage at a 1925 beauty convention in Chicago; Mrs. Ruth Maurer — who presided at the opening session and ran a popular beauty brand and training schools — was quoted in papers around the country saying, “Painted knees are the latest thing. Hand-painted pictures on the knees are intriguing. Some designs are simple, some elaborate. Some girls prefer a flower or a group of blossoms. Others like a portrait or a little landscape.”

An article syndicated in publications ranging from the Pittsburgh Press to the San Francisco Examiner to the Fort Worth Record reported humorous examples (maybe true or not) of the trend, like a housewife who painted her two dogs, which her husband hated. He retaliated by decorating his own knees with portraits of the town’s two most attractive women. Mary Bell, a 17-year-old in Omaha, Nebraska, combined knee art with the Scopes Monkey Trial, a high-profile legal case at the time concerning the right for human evolution to be taught at state-funded schools in Tennessee. For a dance, she paired an illustration of Clarence Darrow (the lawyer defending science-based curriculum) on one knee and a monkey on the other. Her look made such an impression she made the evening paper. Even famed inventor and cartoonist Rube Goldberg supposedly took part, painting the knees of some of Broadway’s hottest dancers.

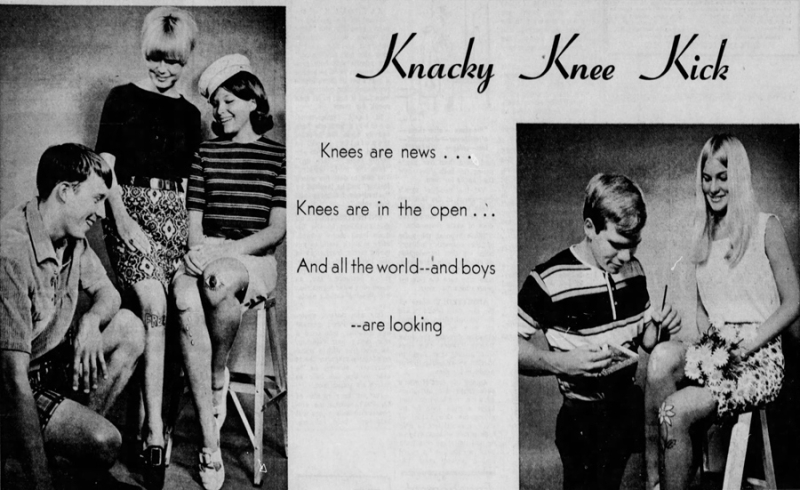

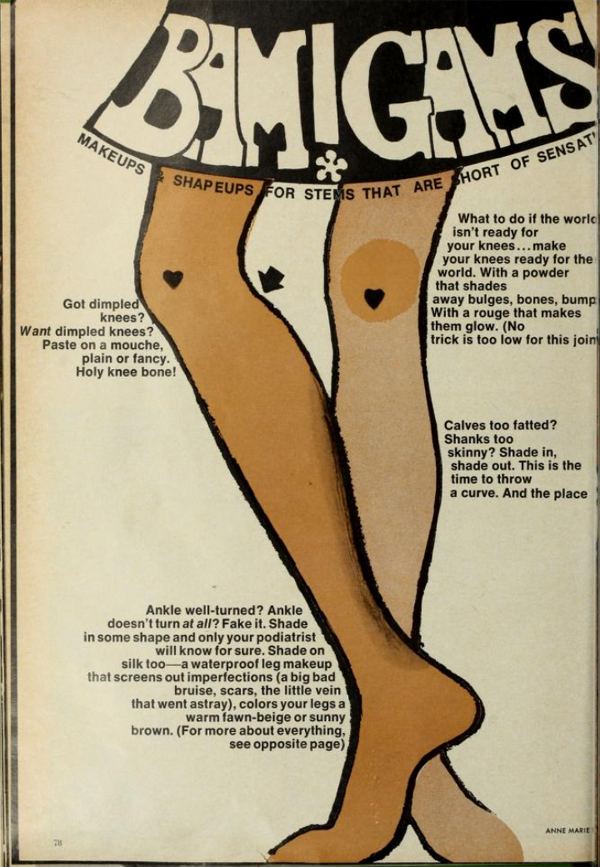

Knee art died out by the Depression (though during the rationing war years, inventive women used eyebrow pencils to draw the impression of stocking seams and temporary tattoos gained popularity in the 1950s as 1-cent sheets). But the style experienced a revival in the ‘60s, along with the entry of much shorter hemlines. As Makeup Museum reports, this era saw the rise in makeup artists being heralded for their craft as artwork; William Loew garnered attention for painting a pair of eyes on a model’s knees, in line with the pop art movement. By the mid 1960s, many of the biggest global makeup brands, including Estée Lauder and Revlon began selling knee makeup kits.

The craze also made its way to high school and college students, who used eyebrow pencils, lipstick and magic markers as design tools. Huston Schlosser, a commercial artist, told the Evening Sun in Baltimore Maryland that knee art “might be a good promotion gimmick for selling Bermuda shorts.” Publications even gave suggestions for leftover knee makeup from the summer for the colder months when knees were covered up: “color rouge-and-eye shadow earrings right onto the lobes of your ears.” In contrast to the flappers, some used art to draw attention away from the wrinkly, unattractive nature of knees. One article gave a groovy art tutorial: “circular your kneecaps with alternative stripes of eye liner and eye shadow, till you look as if you’re wearing a piece of 1890s bathing suit.” The trend didn’t seem to make it across the pond: In a 1966 Edmonton Journal article on London fashion, three young Brits said only “kooks” painted their knees. Harsh.

The years since have brought an array of unexpected makeup trends, from fake freckles to colored contact lenses to whatever is the latest nail art fashion on Instagram. What’s special about painted knees is not only that it was one of the few times an underrepresented body part got its fair shake, but also women using their available resources to make their own creative trends, beauty ideals be damned.