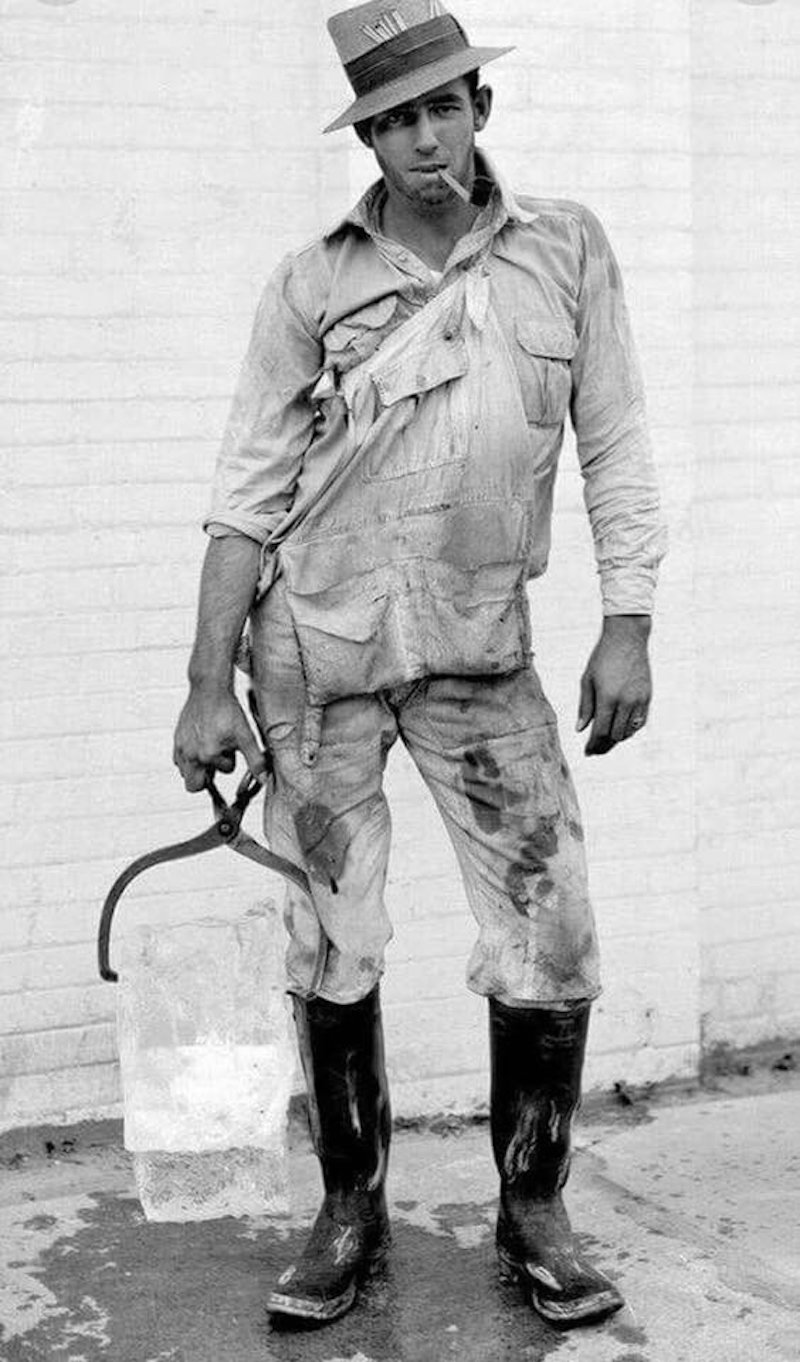

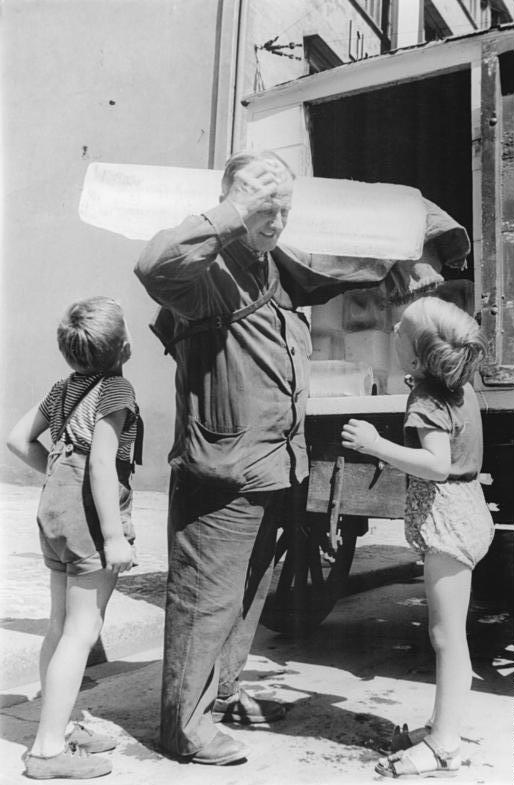

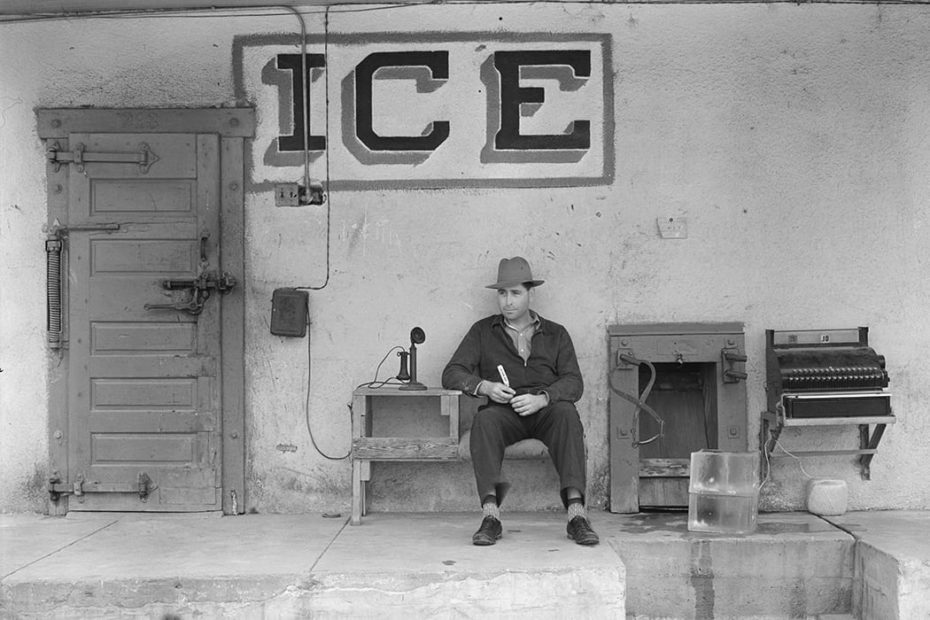

In his autobiography Timebends, Arthur Miller recalls an occupation lost in time – that of the ice man, who wore “leather vests and a wet piece of sackcloth slung over the right shoulder, and once they had slid the ice into the box, they invariably slipped the sacking off and stood there waiting, dripping, for their money.” From the late 19th century to mid-20th century, the ice man (and ice women during wartime) was a common sight in cities and towns where he would make daily rounds delivering ice for iceboxes before the electric domestic refrigerator became commonplace. Today we need only reach into our refrigerator for our personal supply of homemade ice cubes, but depending on where you lived a century or so ago, your ice might have travelled across oceans and continents, surviving over a hundred days without melting, just to chill your drink on a hot summer’s day. The ice trade revolutionised the meat, vegetable and fruit industries in the 19th century, enabled significant growth in the fishing industry, and encouraged the introduction of a range of new drinks and foods. At the height of its trade, ice, as it happens, was once America’s largest export after cotton.

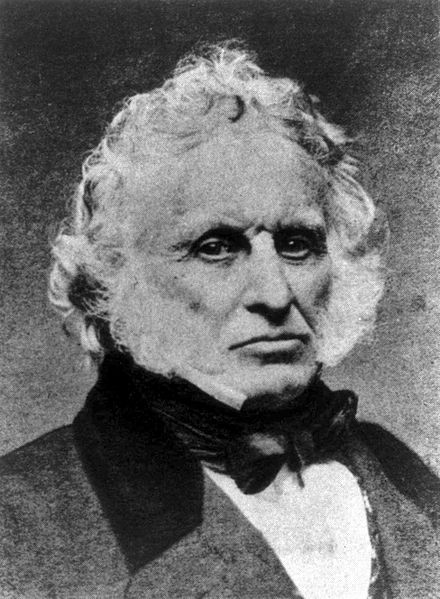

Think of Frederic Tudor as the Henry Ford or the Rockefeller of the ice trade. He became known as “The Ice King” and became one of the wealthiest people in the world, essentially running a monopoly from the icy ponds of Massachusetts. Before he came along, only the wealthy elite could afford such a luxury as ice, harvested from their own estates and stored in personal ice houses, usually built underground in their gardens. Tudor first tried his luck in the Caribbean, hoping to sell ice cut from his family pond to wealthy members of the European colonial elite.

He was just 23 years old when his first shipment set sail for the island of Martinique, but lost most of his sales when his stocks quickly melted due to lack of storage facilities on arrival. Melting was definitely a problem in those early years of the trade. In the 1820s and 1830s, only 10 percent of ice harvested was eventually sold to the end user due to wastage en route. Of his first 400-ton shipment to Sydney Australia – a 114 day journey from New England – 150 tons of it melted en route. But if you’ve ever struggled to keep your ice from melting away in your picnic cooler on a sweltering hot day, you must be wondering, how did it even work back then? So let’s break it down.

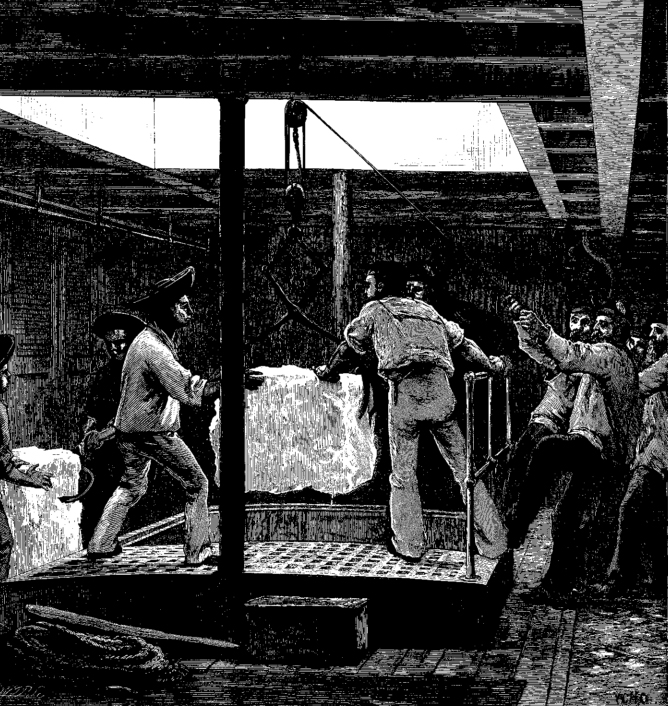

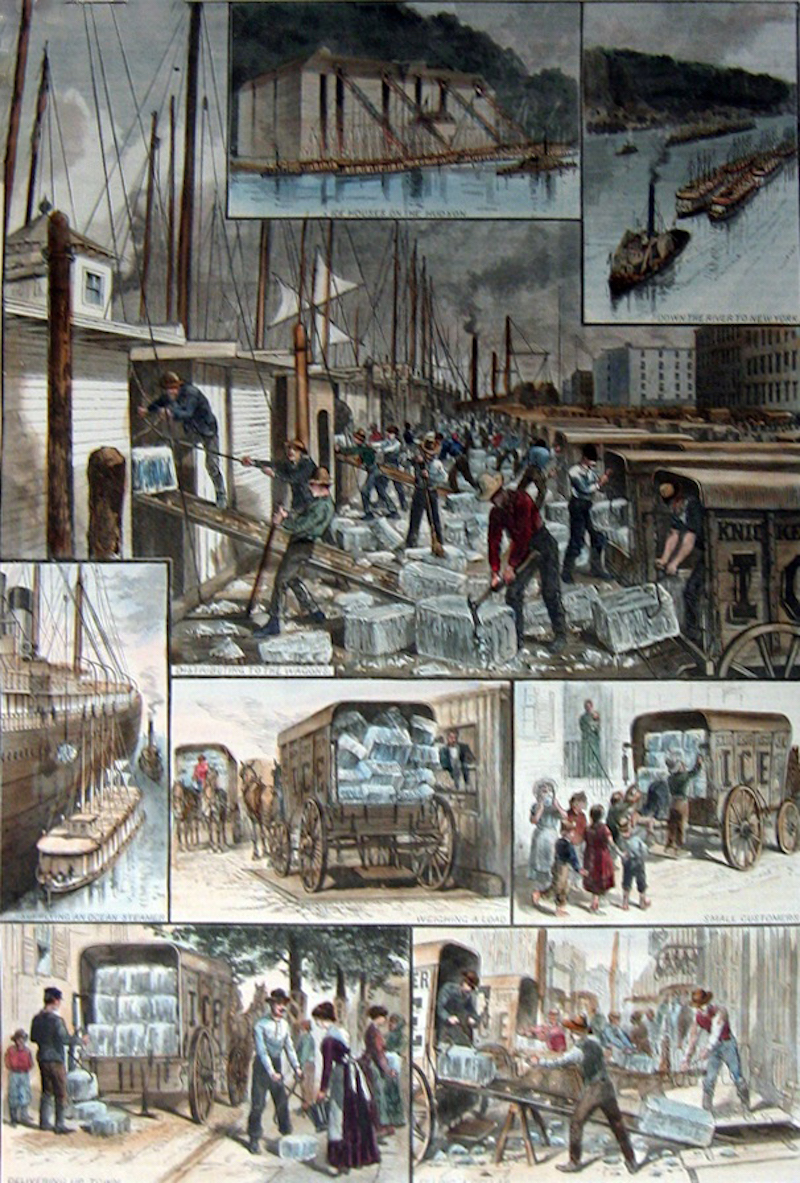

Ice was harvested from ponds and lakes, and most prized was hard, clear crystal ice, typically consumed at the table; while more porous, white-coloured ice was mostly used by industry. It needed to be at least 18 inches thick to be harvested and the size of blocks varied according to the destination, the largest being for the furthest locations, the smallest destined for domestic distribution. The blocks were stored in ice houses before being sent by ship, train or barge to cities around the world.

Fun fact: At the turn of the century, it was the Iceman who took the blame for leading women astray. Icemen had to be in good physical shape, which made his presence all the more concerning to husbands who were away.

Shipping was the most common form of transport for the ice trade and blocks were loaded quickly to prevent the ice from melting, but an average cargo could take two days to load. Typically, the ice was packed up tightly with sawdust and the ship’s hold sealed up to prevent warm air from entering. The large quantities of sawdust required to insulate the ice also helped out the New England lumber industry in the 19th century. Sawdust keeps ice from welding together, traps warm air and cools it to the same temperature to prevent melting. Who knew wood shavings would be a picnic essential? (you’re welcome).

During those early years of Tudor’s trial & error shipments to Martinique and later Cuba, ice held little value. It was generally seen as a free good, or at least, only something the wealthy would be frivolous enough to pay for. But Frederic Tudor was in fact banking on it, and spent much of his energy creating more demand for his product by pretty much inventing the concept of putting ice in drinks instead of only using it for food preservation. Iced drinks were very much a novelty and initially viewed with concern by customers, who were worried about the health risks. He instructed his sales agents to give a year’s supply of free ice to bartenders at social clubs and hotels across the West Indies and the southern US states. While the business community mocked him as a foolish eccentric, Tudor was busy personally teaching bartenders to store ice and make cocktails.

“A man who has drank his drinks cold at the same expense for one week can never be presented with them warm again,” he predicted. Soon enough, drinks such as sherry cobblers and mint juleps that could only be made using crushed ice were created and by the mid-19th century, water was always chilled in America if possible. Demand grew in New York with its rapidly growing economy and long hot summers, and a wave of Southern Italian immigrants took to running the city’s ice routes. The European market was tougher to crack and didn’t adopt chilled drinks in the same way as North Americans, but in Denmark, Frederic did manage to show the keeper of Tivoli Gardens how to make ice cream using his product. That’s right, we can thank Frederic too for the large-scale production of ice cream, which also resulted from the ice trade.

At its peak at the end of the 19th century, the U.S. ice trade employed an estimated 90,000 people. By this time, Norway had become a major competitor, exporting a million tons (910 million kg) of ice a year. And during the California gold rush, ice began to be ordered from the then Russian-controlled Alaska to keep up with demand. Once Tudor had single handedly kickstarted the ice trade, suddenly, the right to cut ice became very important and claim to lakes, ponds and rivers had the potential to spark serious disputes. And when it came to the availability of ice, it wasn’t always smooth sailing. Warm winters could cripple an ice harvest, which became known as “ice famines”. Tudor was so desperate one winter, he allegedly sent his ship’s captain to hack off part of an iceberg.

Meanwhile, the end of the ice trade was in sight before it even began. It had been known as early as 1748 that it was possible to artificially chill water using mechanical equipment. Granted, the early technology was unreliable; early ice plants were constantly at risk of exploding, the ammonia-based approaches potentially left hazardous ammonia in the ice and for most of the 19th century, artificial ice was not as clear as natural ice and less suitable for human consumption. But with industrialisation, the contamination of natural ponds and rivers also became a serious problem for the natural ice trade. By 1914, 26 million tons of plant ice was being produced in the U.S. each year compared to the 24 million tons of naturally harvested ice.

It was only a matter of time before refrigeration cooling systems would change everything and the inter-war years saw the total collapse of the ice trade around the world. The introduction of cheap electric motors resulted in domestic, modern refrigerators allowing ice to be made in the home. Little remains of the 19th-century industrial network; the harvests shrunk to insignificance, ice warehouses were abandoned or converted for other uses and the ice man disappeared from the city streets. The occupation of ice delivery lives on through some Amish communities, where ice is commonly delivered by truck and used to cool food and other perishables.

Of course, Frederick Tudor was dead long before refrigeration became affordable to a mass market, but the next time you’re refreshing yourself with an iced drink this summer, make a toast to the stubborn and eccentric merchant who brought ice to the world. And pour one out for the lost profession of the ice men and women while you’re at it.